The Rise and Fall of Hunter S. Thompson (Part 2 of 3)

I continue my tale of fear and loathing in the journalism trade

Below is the second installment (out of three) of “The Rise and Fall of Hunter S. Thompson.” This is the latest in an ongoing series of essays on counterculture figures—including (so far) Jack Kerouac, Frank Zappa, Bob Dylan, Joan Didion, Eden Ahbez, and Gregory Bateson. These are currently available only on The Honest Broker.

For part one of this essay, click here.

Please support my work—by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

The Rise and Fall of Hunter Thompson (Part 2 of 3)

By Ted Gioia

Thompson now had the recipe for his journalism career, and it involved three conceptual breakthroughs.

The story behind the story is the real story.

The writer is now the hero of each episode.

All this gets written in the style of a personal communication to the reader of the real, dirty inside stuff—straight, with no holds barred.

Why couldn’t you write journalism like this? In fact, a whole generation learned to do just that, mostly by imitating Hunter S. Thompson.

But it grows tired and predictable in the hands of today’s imitators—and the Gonzo King never invited either of those modifiers. Yes, blogs and Substacks are part of his legacy, formats that blur the line between diary, confession, and journalism. But he did it before all the rest, not as a desktop publisher—instead putting his life at risk on the road with total fear and loathing.

So if Substack is the grandchild of Hunter Thompson and New Journalism, it is a tame, well-behaved descendant—and nothing like its brave forebear, who kept going full speed without a helmet until the end.

Even the reader has to run to keep up.

III.

I need to tell you about “New Journalism” at this point.

That was name given to a disruptive style of writing that shook up print media in the 1960s. Authors started breaking the old rules—making their stories more subjective and freewheeling. They wrote journalism that borrowed techniques from fiction, and crafted an immersive style of writing that let readers feel as if they were part of a shared experience.

The leaders of the movement included Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, Gay Talese, and Joan Didion, among others. Their guiding light was a paradoxical view that writing got more real the less it stuck with the facts.

Contradictions of this sort were everywhere in New Journalism. Just consider the strange anomaly that non-fiction novels became a prominent vehicle at this juncture. But nobody dove into paradox more boldly than Hunter Thompson, who filled his dispatches with imaginary sources, unreal incidents, false chronologies, and other techniques better suited for criminal alibis than reporting the news.

Hunter Thompson is now lauded as a leader of New Journalism, but he arrived late on the scene. As early as 1960, Norman Mailer was pushing at the constraints of political reporting in his Esquire article “Superman Comes to the Supermart.” And over the next several years, Gay Talese would publish a series of influential New Journalism pieces in that same magazine, including “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” “Joe Louis: The King as a Middle-Aged Man,” and “The Silent Season of a Hero” (about Joe DiMaggio). Other early booklength masterpieces of the genre include The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby by Tom Wolfe and In Cold Blood by Truman Capote, both published in 1965.

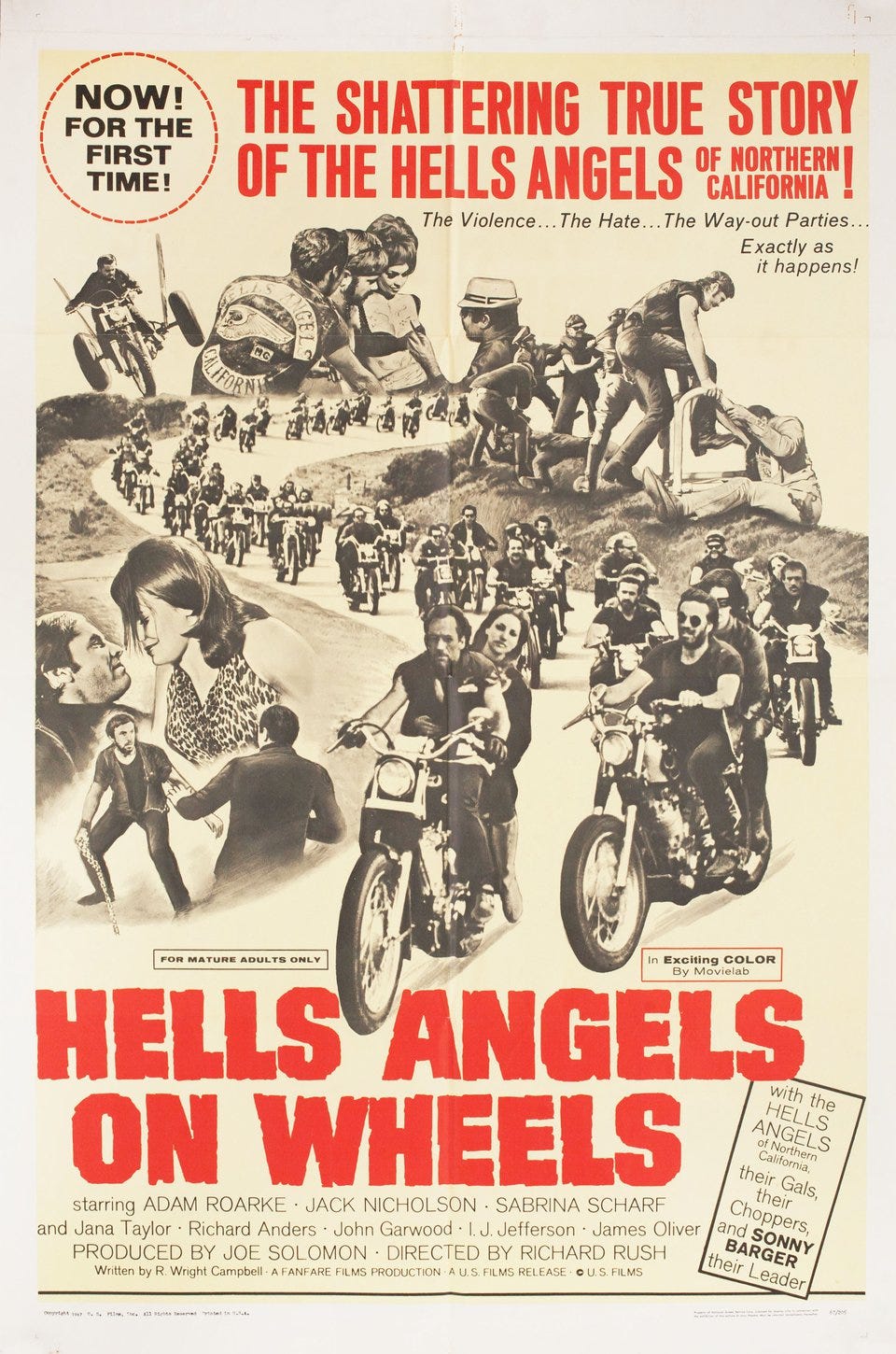

Thompson saw all this happening from afar. The New Journalism scene was centered in New York, while he was roving around Latin America as a correspondent. But when Thompson eventually returned to the US and settled in California, he started looking for suitably immersive stories to write as a freelancer. That’s where he learned about a motorcycle gang known as the Hells Angels, who were starting to generate a lot of negative coverage in the news.

It could have been a simple story—good for a byline and small paycheck. But instead of writing about the Hells Angels, Thompson decided to become an insider, and write from the perspective of the bikers themselves.

Getting involved with a motorcycle gang at this stage makes no kind of sense. Except that it made perfect sense if you were Hunter Thompson. He first parlayed this stint of road rage into a successful 1965 article for The Nation—which only paid him $100—quite a comedown from the $1,000 fees he had earned from the National Observer. But the real payoff came a few days after his story was published, when seven different book deal offers arrived in the mail. (Other editors probably tried calling him, but Thompson hadn’t paid his phone bills, so the line was disconnected.)

Thompson agreed to write a paperback about bikers for Ballantine, but they soon sensed how big this book could be—so hardcover rights got assigned to Random House. The book generated lots of publicity when released in 1967, but Thompson never quite made the money he expected. The publisher had not printed enough copies at first and couldn’t supply bookstores when demand was at its peak.

Hell's Angels established Thompson’s public persona, but if you read it (as I did) after first consuming his later work, it seems cautious by comparison. In the early pages, the author works hard to establish his credentials as a respectable journalist—offering up statistics, quotes from government reports, and paragraphs filled with names and facts. But even at this early stage, Thompson must have grasped that his readers wanted something more. So as the book progresses, it gets weirder and weirder.

Later Thompson came up with the quip: “When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.” And that’s what happens around page 125 of Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga. Thompson never actually became an official member of the gang, but from that point on, the distinction is purely academic. He’s out there boozing, procuring, running interference with police, and putting his life and property in constant danger. The bio on the book’s dust jacket sets the tone: “He is known as an avid reader, a relentless drinker and a fine hand with a .44 Magnum.”

Three incidents in the book give us a taste of Gonzo journalism in full flight. In a historic juxtaposition, Thompson set up a meeting of the Hells Angels and Ken Kesey’s LSD-imbibing Merry Pranksters—one of the defining confrontations of the decade. He’s lucky it didn’t collapse into rampant violence, as even Thompson realized at the time. Take dozens of rowdy, well-armed bikers already high on beer and introduce them to hallucinogenics at a wild party, and you may soon rack up a sizable body count. But somehow the LSD (still legal at the time, but not for long) had a pacifying effect on those East Bay bad boys.

The same cannot be said of the other two classic scenes in Thompson’s book. In its denouement, Thompson gets stomped by several of his former biker buddies, and sent off to the hospital emergency ward. And a final poetic epilogue describes Thompson taking a dangerous ride on his bike, almost suicidal in intent.

Those were the passages that set the tone for all his future work. And his life too. The theme of suicide emerges too many times over the years, long before his self-caused death at age 65. The same year he embarked on the Hells Angels project, he wrote to a friend: “The one thing I insist on is that I can’t be croaked , except when I give the word.” To another correspondent he described suicide as “the only logical human act.”

To his credit, Thompson may have arrived late at the New Journalism party, but he was taking bigger chances than any of them. Wolfe and Mailer and Capote were outrageous figures, no doubt—but had any of them gotten ass-whupped by bikers in order to get a story?

Despite the success of Hell’s Angels, Thompson’s career stalled during the mid-1960s and the immediate momentum from the book led to numerous dead ends.. He agreed to write a book on the American Dream for Random House, but couldn’t find the right angle. He worked on novels, but couldn’t get them published—although The Rum Diary finally showed up in bookstores in 1998 (and was later turned into a Johnny Depp film).

Playboy refused to publish the profile article on Jean-Claude Killy it had commissioned. Esquire hired Thompson to write a 3,000-word article on the National Rifle Association, and he submitted an unusable 80,000-word manuscript that was promptly rejected. Even Thompson’s old standby, the National Observer, finally grew tired of his theatrics.

He did make progress in some areas during this period—but typically on absurd or futile endeavors. He saw an ad in the back of a magazine that offered ‘doctor of divinity’ degrees for five dollars—so the future Gonzo King sent off for one, and from that time forward was “Dr. Hunter S. Thompson.” In the middle of conversations, he would sometimes remind his interlocutor that “I am, after all, a doctor.”

More serious, but still futile, was his immersion into politics in his new home of Aspen, Colorado. In a series of campaigns to demonstrate “Freak Power”—the potential impact of young, disgruntled voters of various constituencies—Thompson tried to take over City Hall, and establish himself as Sheriff.

To his credit, Thompson mobilized a meaningful group of supporters, albeit insufficient to earn him a sheriff’s badge. But a more fruitful long term result was an assignment from a new upstart periodical to cover the campaign.

The magazine was Rolling Stone, still just a few months old but already shaking up the scene. Editor Jann Wenner wanted to enhance his imprint’s counterculture credentials, but even he must have wondered what he was getting into with Dr. Thompson. After their first encounter—mostly a 45-minute monologue from the journalist himself—Wenner turned to his colleagues and said: “I know I’m supposed to be the spokesman for American Youth Culture and all, but what the fuck was that?”

That was the typical reaction of Thompson’s closest collaborators during this final stretch toward journalistic fame. British illustrator Ralph Steadman had a similar shock on first encountering HST in the flesh. Steadman was literally on his first day in the United States when he got hired to go with Thompson to cover the Kentucky Derby—initiating a partnership that (as with Wenner) would last decades. “It was my first time in America, and I hit a bull’s eye,” he later reminisced. “I met the strangest man in America.”

The stars were now aligned for the birth of fear and loathing on the road. The optimism of the 1960s had now faded, and a bitter aftertaste left young readers thirsty for a more insurgent form of journalism than even Talese or Mailer could provide. Thompson’s Kentucky Derby article, for Scanlan’s Monthly, published in June 1970, was his first demonstration of this new style—it was so strange that even the author was apologizing for it before it stirred up so much acclaim. And now Rolling Stone—the voice of “American Youth Culture”—was ready to finance, support, and edit the most unhinged writer on the scene.

Let’s stop for a moment and savor the incongruity. Hunter Thompson, now in his thirties, was a full decade older than the Baby Boomers. And with his balding head and furrowed brow, he looked more like an Ancient Mariner than a young rebel.

You would never mistake Thompson for a hippie. He was a married man with a child, raised in Kentucky during the Great Depression and WWII years. He was a former airman in US military now living on a farm in Colorado with his family and a bunch of firearms.

Could this faux doctor of divinity really set the tone for the youth movement, the peace-and-love crew, the freaks and rebels? Could he have clout on Haight and Ashbury or amid the rumblings of post-Woodstock America?

We would soon find out.

Click here for the third and final installment of “The Rise and Fall of Hunter S. Thompson.”

I actually met Hunter Thompson on a plane. I was a flight attendant in first class and he was there. The man was such a mess that he couldn’t discern what was the flush button and what was the call button. I had to save the man from the first class lav. As we had a passenger manifest and I had also enjoyed his Rolling Stone article I knew it was him. I asked him, “Are you okay Mr Thompson” and was met with “DOCTOR Thompson”.

He drew a picture of me on a napkin and signed it. What I ever did with it is a mystery. I’m just not a collector of signatures and he just gave me the napkin cuz I rescued him from the toilet I guess.

Ending reminds me of how many of the iconic figures of the 1960s - early 70's were actually Silent Generation folks. Worth exploring sometime.