My Survey of 16 Classic Works of New Journalism

Let's make New Journalism new again

Journalism is changing rapidly—faster than at any point in my lifetime.

Outsiders are breaking rules and shaking up the system. And insiders can’t ignore them anymore.

They need to adapt, or die.

Business as usual is no longer an option. Every week I see new rounds of layoffs at media outlets that refuse to acknowledge the shift. Meanwhile many alternative outlets are growing by double digits (or triple digits, here at The Honest Broker, where we’re up 130% in the last year).

When change happens this quickly, there’s no place to hide.

We’re lucky to have a role model for reinventing journalism. They called it New Journalism back in the 1960s and 1970s.

It’s not new anymore. But maybe it could be—setting an example for a new generation of writers.

If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

The New Journalists took risks—and I’m not just using a metaphor. When Hunter Thompson wrote about the Hells Angels, he ended up in the hospital.

Editors, by comparison, were easier to deal with—they don’t carry switchblades. So the New Journalists typically ignored marching orders from home office, instead following a story wherever it took them.

They loved exposing corruption and hypocrisy. They battled the system, and were willing to make powerful enemies. They didn’t back down.

We need all of those things right now.

But their books and articles are also bona fide page-turners—the New Journalists rank among the finest prose stylists of the last 100 years. Along the way, they created an entirely new way of reporting on current events, drawing on the techniques of fiction to describe real people and incidents with unprecedented immediacy and intensity.

By comparison, the listicles and down-sized media bites of the current day are sad things indeed.

16 Classic Works of New Journalism

I sketch out the highlights of the movement below with an annotated guide to 16 classics of New Journalism.

They are listed below in chronological order.

Lillian Ross, Picture, The New Yorker, May 16, 1952

When fans congratulated Truman Capote for inventing the non-fiction novel with In Cold Blood (1966), he graciously pointed out that Lillian Ross had done it first—with her work Picture, which appeared in five installments in The New Yorker in 1952.

Here Ross follows the history of a single Hollywood film, The Red Badge of Courage, which made little stir at the box office, but led to the end of Louis B. Mayer’s reign as head of MGM.

The term New Journalism didn’t exist back then, but Ross was putting together all the key ingredients that would later blossom in that influential movement. Ross herself appears as a character in the background of the book, but she lets the film people do all the talking and acting. The result is a major work of longform journalism, and one of the best books ever written about the entertainment industry.

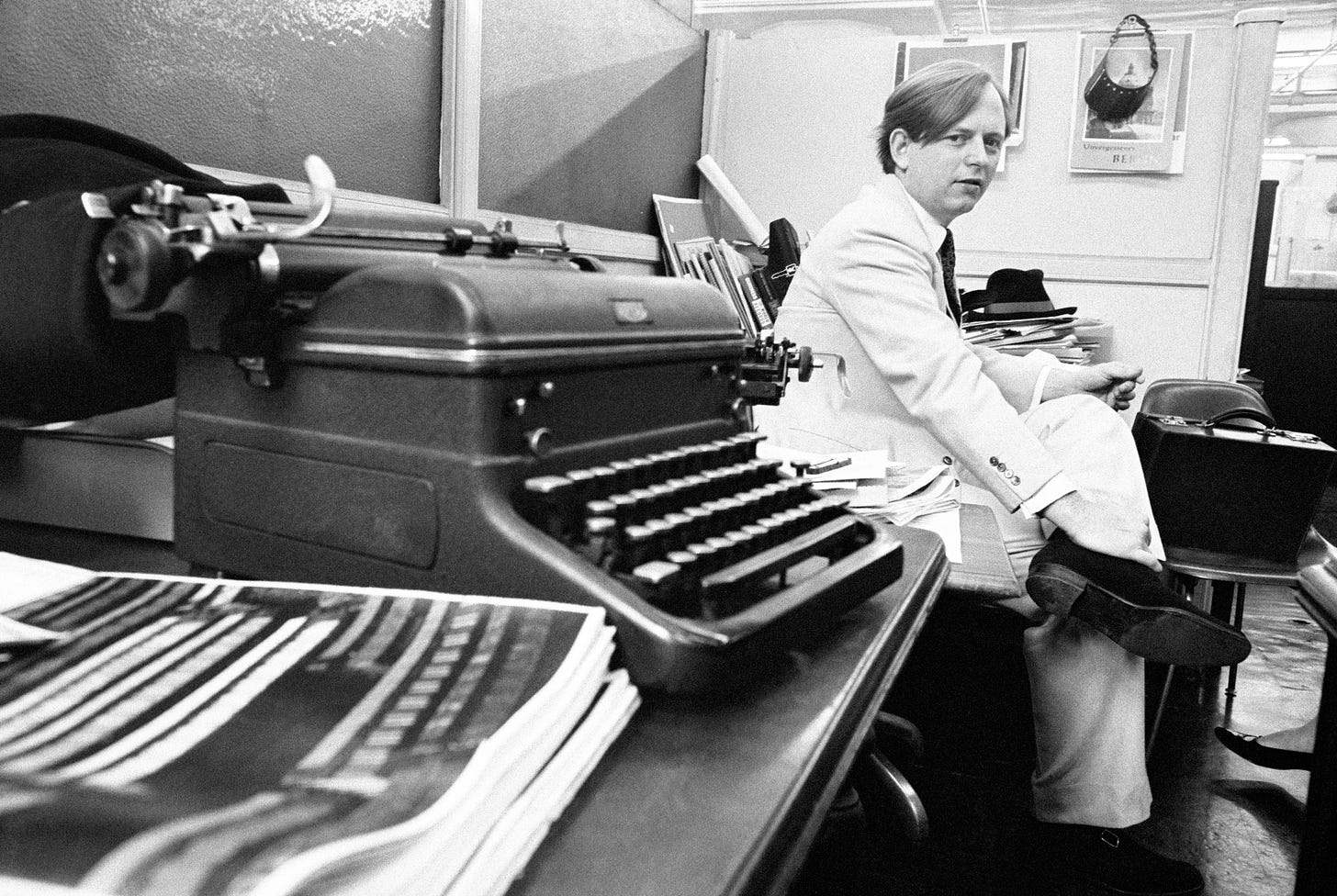

Tom Wolfe, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, June 28, 1965

I read this book when I was in high school, and was dazzled by its flashy prose and extravagant pose. Nowadays, it seems a bit much, and I would tone down some of these paragraphs.

How many times does Wolfe really need to use the word arteriosclerotic in these pages—to dismiss everything that happened before his day?

But, in all fairness, there was a lot of artery-blocking culture in the early 1960s. Maybe today, too.

You might have noticed the cover page blurb by Kurt Vonnegut: “Verdict: Excellent book by a genius.” But the publisher tactfully leaves out the more revealing full quote, which was originally:

“Verdict: Excellent book by a genius who will do anything to get attention.”

That pretty much sums it up.

But the 28 essays in this book are still loads of fun, and must have been a revelation to other journalists during the LBJ years. (Sorry, kids, that’s not LeBron James.) Here Wolfe looks at fast cars, rock music, Las Vegas, and any other way you can roll the dice, literally or symbolically.

Soon a whole generation would be writing like this, but few with the consistency, panache, staying power, or pristine white suits of Tom Wolfe.

Truman Capote, In Cold Blood, The New Yorker, September 25, 1965

This innovative non-fiction novel first appeared as a four-part serial in The New Yorker, and caused a sensation from the outset. Capote’s account of the murder of the Clutter family in Holcomb, Kansas, and the subsequent criminal prosecution of two drifters, was written with a taut, poised prose style and captured a literary suppleness never before found in true crime narratives.

It was almost as if Capote, in this tiny Midwest town, had found his path to becoming the American Zola or Balzac.

Random House released a book edition in January 1966, and it was a runaway bestseller. In Cold Blood would eventually get issued in some 250 editions, translated into 30 languages, and adapted twice on the screen. The book deserves every bit of its acclaim, but Capote proved incapable of building on its success—he published little in the two remaining decades of his life, except for the controversial Answered Prayers (see below).

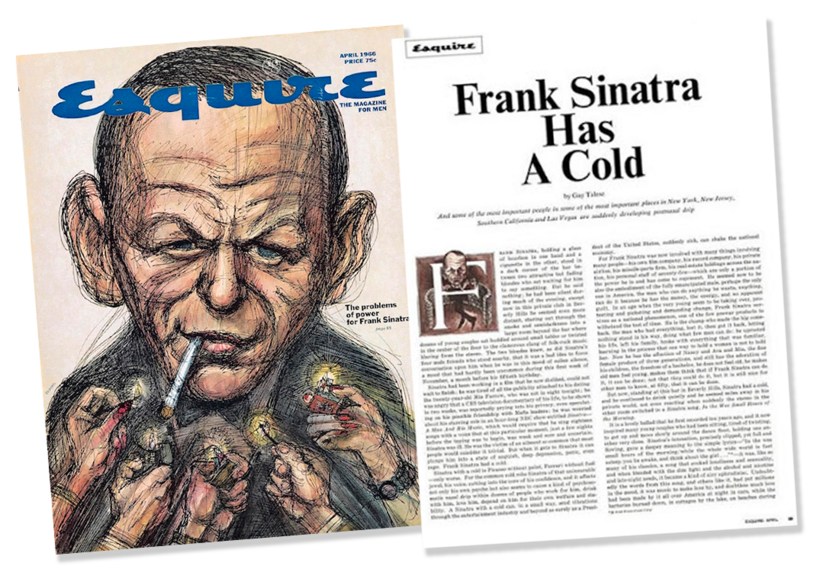

Gay Talese, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” Esquire, April 1966

This may be the most famous piece of music journalism from the mid-1960s. But I avoided reading it for many years, because the whole concept seemed like a stunt.

Talese was unable to get an interview with Frank Sinatra, and had to resort to an indirect, observational style of writing—built on glimpses, asides, and secondhand testimonies.

This didn’t seem promising to me, until I actually read Talese’s essay. He spent three months on Sinatra’s trail, and got a much more interesting story than those slick interviews in other slick magazines.

Above all, Talese revealed here (and elsewhere in his collected work) amazing restraint. Unlike some other New Journalists of a more gonzo persuasion, he never intrudes on his story, but lets it develop on its own terms and at its own pace. I can’t think of another magazine article on American popular music that I admire more than this longform essay.

Jean Stafford, A Mother in History, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1966

The New Journalists loved pop culture stars, but they were even more obsessed with violent criminals.

Journalists have always like crime—it sells newspapers, after all. But they rarely probed into the psychological underpinnings of the perpetrators. If you wanted that, you turned to Dostoevsky, not the daily news.

But during the mid-1960s, a Dostoyevskian sensibility entered the New Journalism movement, most famously in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, but also in this trenchant non-fiction classic A Mother in History.

Jean Stafford traveled to Texas to spend time with Marguerite Oswald, mother of JFK’s assassin. Over the course of several days she compiled nine hours of taped interviews. The resulting short book transcends crime journalism and instead presents a case study in maternal denial and desperate spin.

Stafford faced a huge backlash. Readers complained that her work served to “enthrone a wicked woman” and “demolish the sacred throne of motherhood.” Time magazine called A Mother in History “the most abrasively unpleasant book in recent years.”

Well, it might be that. But it’s a lot more.

Gay Talese, “Joe DiMaggio and the Silent Season of a Hero,” Esquire, July 1966

In the aftermath of his eccentric Sinatra article (see above), Talese tackled an even more tight-lipped middle-aged Italian-American. But dealing with suspicious Sicilians was now his specialty.

Talese grapples here with Joltin’ Joe DiMaggio, now in late middle age, and with his baseball career and marriage to Marilyn Monroe deep in the rearview mirror. A few months later, Simon & Garfunkel would ask: “Where have you gone Joe DiMaggio?” in the lyrics to a megahit song, but readers seeking an answer only needed to track down this issue of Esquire.

If you want to become a superstar journalist in the present day, just learn how to write celebrity profiles like this one. But how many have the talent and persistence to pull it off?

Hunter S. Thompson, Hell’s Angels, Random House, 1967

About 100 pages into this book, American journalism starts to change before your eyes. In the opening chapters, Thompson acts like a responsible reporter, citing statistics, quoting experts, and serving up various sociological theories for your dissection.

But then something shifts, and instead of observing motorcycle gang members, Thompson starts acting like one himself.

He actually used the advance for the book to buy his own motorcycle—maybe the most symbolic transaction in the history of late 20th century journalism. He was arrested three times within the next month.

Before the book is over, Thompson is just as crazy as the worst of these desperadoes. He even has to go to the emergency room after getting stomped on by his new biker buddies. With friends like these, who needs enemies?

We’re lucky he survived, because his strangest book was still ahead of him (see below).

Joan Didion, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” Saturday Evening Post, September 23, 1967

The world was changing in 1967, and Joan Didion confronted it firsthand in Haight-Ashbury, where a new hippie society was in the ascendancy. Here she encountered everything from peace & free love all the way to pot & free LSD.

This was a strange, intoxicating brew indeed, but Didion never gets high on it. At every step, she strenuously avoids the wannabe posturing that, for example, Hunter S. Thompson would have brought to the same setting. Didion somehow floats above the craziness, maintaining a penetrating outsider’s gaze even as she operates in the middle of the strangest proceedings.

This is a case study in how immersive journalism ought to be conducted, with all the independence and brutal honesty the profession demands—but so rarely achieves. Even today, when so many other narratives from the late 1960s are laughable and hopelessly dated, this account retains all its authority, revealing a vanished world that nobody described half so well.

Tom Wolfe: The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, August, 1968

The New Journalists sought out the most extreme subjects for their stories, which were usually happening out West—in Haight-Ashbury or Las Vegas or on the road with motorcycle gangs.

But Wolfe may have found the most rebellious group in all of California: Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, who took LSD tabs like they were M&Ms, and brought their non-stop party on the road in a psychedelic bus, driven by counterculture legend Neal Cassady (inspiration for Jack Kerouac’s On the Road).

In a long, illustrious career, Wolfe never had a better subject, and delivers an iconic text of 1960s rebellion.

Hunter S. Thompson, “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” Rolling Stone, November 11, 1971

Is this really journalism? Frankly, I’m not sure.

I love Fear & Loathing, but would hate to be the fact-checker at Rolling Stone asked to verify everything in Thompson’s gonzo tribute to Sin City. It would be like trying to add footnotes to a feverish dream.

But I put such scruples aside. What Thompson loses in objectivity, he regains via a double dose of subjectivity, assisted by various illegal substances. The result is a portrait of the journalist as a young maniac—hellraising in prose that nobody has since surpassed. Not even Thompson himself, although he tried repeatedly in later years.

Norman Mailer, Existential Errands, Little Brown, April 17, 1972

Sooner or later, any student of New Journalism needs to deal with Norman Mailer—but my advice is to make it later.

He was constantly getting high profile journalism assignments, and delivering painfully narcissistic manuscripts. They have not held up well with the passing decades.

This collection of 28 pieces from the late 1960s and early 1970s finds him on the front lines in the movement, and the attentive reader will enjoy occasional moments of insight and fine writing. But many of the subjects that attracted Mailer (criminals, astronauts, pro athletes, celebrities, etc.) were tackled with better results by Capote, Wolfe, Talese, and Didion.

Yet in some ways, it doesn’t really matter—with Norman Mailer the subject of the story is always just Norman Mailer. And sometimes he does fascinate us through all the crapulence.

Truman Capote, “La Côte Basque 1965,” Esquire, November, 1975

Capote had a grand idea for a follow-up to In Cold Blood—he would write the great gossip novel. And few people knew more dirty gossip than Truman Capote.

He planned a book entitled Answered Prayers, taking the title from Saint Teresa of Avila’s assertion that “More tears are shed over answered prayers than unanswered ones.” In some ways, the whole history of this failed book is summed up in that epigram.

When Capote published three chapters of his gossip novel in Esquire, his friends were shocked to see their most intimate tales revealed in print. Some never forgave Capote and many ostracized him in the aftermath. He never recovered his momentum as a writer—or human being—after that point.

Despite collecting large—and repeated—advances from Random House, he never delivered a finished manuscript. Upon his death, no additional chapters were found—so the edition of Answered Prayers that exists today consists only of the three sections published in Esquire, supplemented by a brief fragment called “Yachts and Things.”

Even so, I refuse to call this book a failure. Despite its abbreviated form, Answered Prayers is a page-turner, and supports Capote’s assertion that gossip is a powerful narrative form with untapped literary potential.

Joan Didion, The White Album, Simon & Schuster, 1979

For the record, let’s make clear that the Beatles’ White Album never appears in this book. But Didion made a career of defying expectations.

Consider the opening of this simmering work, where she starts by announcing her insider acclaim as an LA Times ‘Woman of the Year’ for 1968—and then proceeds to share her hospital reports as a psychiatric patient during the same period.

As the book proceeds, the reader is never quite clear whether our author is the most unhinged writer in SoCal or a paragon of sober reporting. But like the unmentioned Beatles record, Didion’s The White Album stands out all the more for its rule-breaking, and is a legit classic of the era.

Tom Wolfe, The Right Stuff, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1979

Before shifting gears, and turning into a novelist and culture critic, Tom Wolfe delivered one final book-length example of New Journalism at its finest.

The Space Race was a tired old story by the time Wolfe turned to the subject—after all, Norman Mailer had published Of a Fire on the Moon back in 1970. But Wolfe understood that all those pompous hero-worshipping narratives failed to capture the true space oddity of the astronauts’ everyday lives.

The actual story was wilder and crazier than anything reported in US media during the moonflight years. In many ways, these riders of the purple cosmos were more like those Hells Angels that Hunter Thompson had celebrated back in the 1960s.

Wolfe reins in his own tendency to excess, and lets his story tell itself, with just the right seasoning of authorial interference. Even today, when spaceflight has turned into a banal corporate business, this book still takes off like a rocket.

Norman Mailer, The Executioner’s Song, Little, Brown, 1979

Did this bloated book signal the end of New Journalism? Here Mailer tried to out-do Capote’s In Cold Blood, with a comparable true crime story. And he certainly beat Truman in terms of word count.

The Executioner’s Song is more than a thousand pages, and tells you everything you ever wanted to know about murderer Gary Gilmore, who made headlines by demanding that his death penalty sentence be carried out as soon as possible—and even requested a firing squad.

But here’s Truman Capote’s assessment of his rival’s book:

He didn’t live through it day by day, he didn’t know Utah, he didn’t know Gary Gilmore, he never even met Gary Gilmore, he didn’t do an ounce of research on the book—two other people did all of the research. He was just a rewrite man like you have over at the Daily News. I spent six years on In Cold Blood and not only knew the people I was writing about, I’ve known them better than I’ve known anybody.

Okay, Capote is a little catty—but this is not an unfair assessment.

In any event, Gilmore’s case was grisly news story for a few weeks in 1977, and would have soon been forgotten if not for Mailer’s gargantuan book. But the story is too thin for this amount of verbiage, and though Mailer got his usual fawning reviews and awards, he delivered a kind of tumescent journalism that other writers might possibly decide to read, but really shouldn’t emulate.

Janet Malcolm, “Trouble in the Archives,” The New Yorker, December 5, 1983

This is a classic of longform journalism, and one of the best pieces from The New Yorker during the early 1980s. But it caused no end of grief for Janet Malcolm, whose exposé of a flamboyant psychoanalyst (later published in book form as In the Freud Archives) led to intense legal skirmishing.

The story is fascinating: Sanskrit scholar Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson changes careers and becomes a shrink—then somehow turns the whole world of Freud upside down, in ways that eerily echo all those wild theories about transference and Oedipal complexes.

The Supreme Court eventually sided with Malcolm, but this brouhaha made clear that the loose and wild world of New Journalism, with its heavy borrowing of fictional techniques, wasn’t a good fit with the more corporate tone of the 1980s.

I’d like to see more writing like this today. And the time is ripe—corporate media no longer has a lockhold on journalism.

Reporters don’t need permission anymore to tackle controversial stories. They don’t need to obey editors. They don’t need to worry about uptight advertisers.

They can speak directly to readers.

We might not get another Hunter Thompson or Joan Didion. But, then again, we might. We should at least be on the lookout, and give new voices support when we find them.

I’ll try to do that here.

Ted...I must dissent from your opening remarks. If you look back at that golden era, I think you will find that every "new journalist" had a great editor. Without Arnold Gingrich at Esquire, no Tom Wolfe, who famously thought he had flamed-out on his first assignment, sent a letter to Gingrich with notes for another reporter; Gingrich simply lopped off the "Dear Arnold" and ran with it. Fame ensued.

Ditto Clay Felker...ditto (believe it or not) Jann Wenner...with an assist from WaPo's Ben Bradlee, who started "Style," the first autonomous daily newspaper features section. (Which were the first to get the chop when newspapers imploded.)

Some writers came up with these stories on their own--but most were sent scurrying out to satisfy a great editor's boundless curiosity. These same editors on the "soft" side of the news biz often had to defend those writers against the "hard" side, which wanted stories every damned day--you had to "fill" the spaces around the Macy's ads, after all. But great journalism, "new" or otherwise, takes time and an expense account.

(The author of this piece confesses a conflict of interest since he edited feature sections at several once-profitable American newspapers.)

At the risk of dating myself, I was a wayward youth from the hinterlands who found himself at a certain West Coast school in the 70s because I could take tests and throw a baseball with my left hand. My RA took me to an off-campus dinner party gathering of her upperclassmen (and upper class) friends. I knew which fork to use because my countryfied mother insisted throughout my life that manners would pay off, but then we played charades. The card I drew was Fear and Loathing. I'd never heard of HST--he wasn't on my Texarkana public school reading list (I can, however, still recite the prologue to Canterbury Tales in Middle English). The first time I was embarassed by my ignorance. My fastball didn't mean much inthe PAC-10 either.