“The Only Sensible Person in the World”

10 Perspectives on Joan Didion

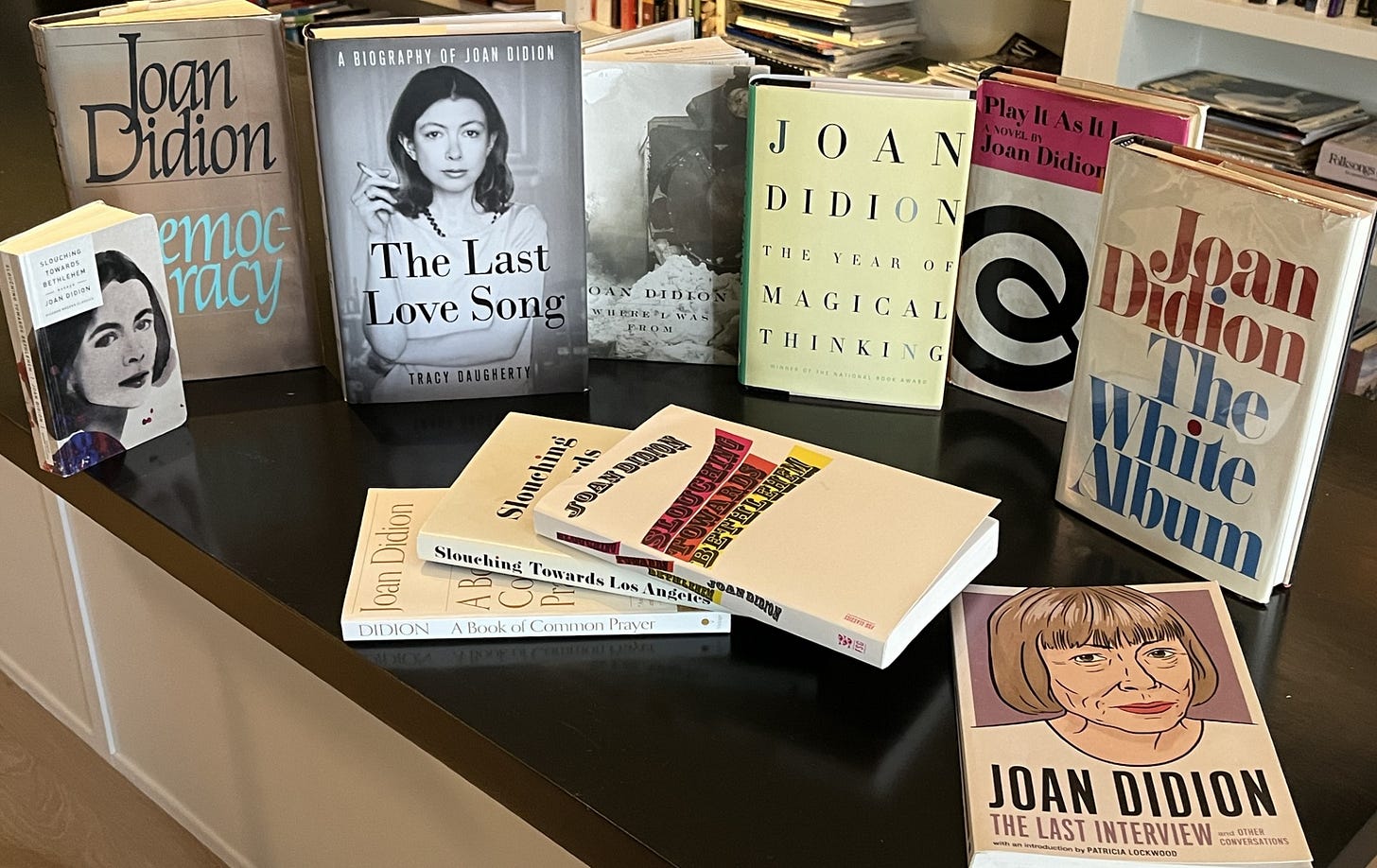

I first read Joan Didion back in college, when her novel Play It As It Lays shook me up like a SoCal temblor. They really ought to measure her books on a Richter scale.

I knew all about existentialist novels back then, but I thought they were only set in France and featured gloomy people in Parisian cafes. But Didion showed me that existentialist angst also existed in my own home town of Los Angeles.

You felt it every time you merged on to the freeway.

I’ve continued to read Didion’s work over the decades. In both her fiction and non-fiction, she taught me ways of perceiving my own milieu on the West Coast that I’d have never learned on my own.

Below are 10 perspectives on Joan Didion—whom I call (borrowing from her friend Eve Babitz) the “only sensible person in the world.”

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

The Only Sensible Person in the World

10 Perspectives on Joan Didion

By Ted Gioia

1.

If you want to know how elusive Joan Didion is, just consider that her celebrated book of essays The White Album never mentions The White Album.

2.

“I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate,” Joan Didion writes at the beginning of her book Slouching Towards Bethlehem. That admission, typical of her disclaimers—her books and essays are full of them—is like her oeuvre, a mix of fiction and non-fiction.

But Didion really was a mass of contradictions.

She saw herself as an archetypal Californian, and did more than anyone to capture the particular West Coast existential angst linked to driving a car. (It runs as deep as the Freudian Id—when Angelenos’ autos are in the shop, a visible malaise actually spreads over their faces.)

Didion herself owned a flashy yellow Corvette. But this is the same writer who admitted in an interview: “I could probably number on both hands the times I’ve driven freeways.”

She didn’t really know how to merge into rapidly moving traffic. (Perhaps she would be more comfortable nowadays when SoCal traffic moves as lethargically as an Academy Awards show). “I can only enter a freeway if it’s at the beginning.”

I could laugh at all this. Instead, I’m beguiled by the notion that LA freeways have a beginning.

3.

One of my favorite passages by Joan Didion was something she didn’t even write.

At a key juncture in her essay The White Album, she shares highlights of a doctor’s file on a psychiatric patient, who suffers from. . . well, pretty much everything:

In June of this year patient experienced an attack of vertigo, nausea, and a feeling that she was going to pass out….

The Rorschach record is interpreted as describing a personality in process of deterioration with abundant signs of failing defenses and increasing inability of the ego to mediate the world of reality….

Her fantasy life appears to have been virtually completely preempted by primitive, regressive libidinal preoccupations many of which are distorted and bizarre….

It is as though she feels deeply that all human effort is foredoomed to failure, a conviction which seems to push her further into a dependent passive withdrawal.

One of the stylish writing tricks Didion learned during her stint as a Vogue editor was to withhold the key detail until the end of a passage or paragraph. That’s precisely what she does in this instance.

After a full page-and-a-half of this alarming medical record, Didion explains casually that she is the patient herself.

She writes:

The tests mentioned—the Rorschach, the Thematic Apperception Test, the Sentence Completion Test and the Minnesota Mutliphasic Personality Index—were administered privately, in the outpatient psychiatric clinic at Saint John’s Hospital in Santa Monica, in the summer of 1968, shortly after I suffered the attack of ‘vertigo and nausea’ mentioned in the first sentence and shortly before I was named a Los Angeles Times’ Woman of the Year.’ By way of comment I offer only that an attack of vertigo and nausea does not now seem to me an inappropriate response to the summer of 1968.

I’ve read a lot about the tumult in American society in the late 1960s. I even lived through it, residing just a few miles away from Didion’s outpatient clinic. So I say with full authority, that this might well be the single best summation I’ve encountered of that time and place.

4.

Didion “cooked nonstop,” recalled Eve Babitz.

She continues:

She made stuff like Beef Wellington—for a sit-down dinner for 35 people—with a side dish, Cobb salad or something, for those who didn’t eat meat. It’s the first time I ever saw Spode china. She seemed to be the only sensible person in the world in those days. She could make dinner for forty people with one hand tied around her back while everybody else was passed out on the floor.

5.

Didion’s writing style was, like the author herself, a fusion of opposites.

She loved the short, punchy sentences of Ernest Hemingway, and even tried to internalize the rhythms of his prose by typing out his paragraphs on her typewriter. (Curiously enough, Hunter S. Thompson followed the same practice.) But Didion also admired the ponderous periods of Henry James, with their alluring ambiguities—somehow they managed to grab on to the subject at a deeper level by dancing around it.

From these two opposed influences, Didion created her own prose style. On the surface it seemed straightforward and direct, but the more you studied it, the more open-ended it was. It’s like taking one of those crazy LA shortcuts, where you get to the destination faster by leaving the freeway and dodging through all these mysterious and confusing side streets.

So I’m not surprised that Didion hated the LA freeways she wrote about so pointedly. They were a physical embodiment of the straight paths she abhorred in everything she did.

6.

In her essay, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” Didion captures the uneasy tone of the Haight-Ashbury hippie scene in another first person anecdote.

She is standing with Norris, one of her informants, out on the street, where he suggests she head down to Big Sur to get a taste of the scene there.

Norris says it would be a lot easier if I’d take some acid. I say I’m unstable. Norris says all right, anyway, grass, and he squeezes my hand.

One day Norris asks how old I am. I tell him I am thirty-two. It takes a few minutes but Norris rises to it. “Don't worry, he says at last. “There’s old hippies too.”

7.

How do you establish an independent literary career in Los Angeles—a place where writers are handservants to Hollywood moguls?

For Didion and her husband John Gregory Dunne, the most alluring connection was Christopher Isherwood—a literary lion with a highbrow European aura already in place when he arrived in Hollywood.

But Isherwood was a tough person to enlist in a networking relationship—at least for Didion and Dunne. In his diaries, Isherwood referred to them as “Mrs. Misery and Mr. Know-All.” Didion, he claimed, “spoke in [a] tiny little voice which always seems to me to be a mode of aggression.” She was, above all, a “tragic and presumably dying” woman.

It’s a shame that Didion couldn’t have used those as blurbs on her book covers.

8.

Didion’s later turn to political writing must have surprised many people. She was so out-of-touch with power politics that one interviewer asked her querulously if she even cared enough to vote. (“Once in a while,” she replied. “I’m hardly ever conscious of the issues.”) And her sensibility as a writer, so fluid when dealing with nuance and ambiguity, had nothing in common with the pervasive political rhetoric of the electioneering world.

But it was precisely this grasp of unarticulated truths that made her unique on the campaign trail. I can’t help but be reminded of what a Salvadoran official told her during her on-the-ground research into Central American conflicts: “Don’t say this,” he said off-the-record, “but there are no issues here. There are only ambitions.”

That was something Didion—with residences in both New York and Hollywood—could easily understand, probably even better than journalists on the politics beat.

9.

What makes Didion so elusive is how completely she responds to her setting. Every time she moved into a new context, she reinvented her writing.

She grew up in Sacramento as the child of pioneers—during the Gold Rush days of the 1840s, there was already a saloon in that city called Didion’s. She started out writing about the old West, dealing with John Wayne, the Donner Party, and a mostly forgotten first book, Run River, that was a historical novel about California.

Nothing in her early years, though, prepares us for Didion’s reinvention when she moved to New York to write for Vogue. In a flash, she shifted gears from pioneer daughter of the Wild West to fashionable commentator on Manhattan life. So I shouldn’t be surprised that she adapted just as easily to film writing after her next move to Hollywood, or that she turned into a leading voice in the counterculture after her stint in the Haight-Ashbury.

The effect on the reader is eerie. You feel Didion’s presence everywhere in these writings. Yet you also feel how absolutely transparent she is—as you turn the pages, you believe that you are looking straight through her to the subject at hand, whether biker movies or youngsters dropping acid.

That’s a total illusion. Joan Didion is in total control of the narration at every stage, and actively shapes each scene. But you come to trust her so much, you willingly absorb her perspective into your own.

The last stage in this career of acute sensitivity to the context shouldn’t have surprised anybody. In her final years, Didion emerged as our leading chronicler of aging, loss, and mortality. To cite one example: The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) is one of the most probing books you will ever read about death.

You couldn’t imagine any of the other writers associated with the New Journalism movement making this shift. Certainly not Hunter S. Thompson or Norman Mailer or Truman Capote. They were so caught up in the mythos of New Journalism, they could never adequately write Journalism of the Old. Their output grew less honest over time, while Didion’s became more so.

This is why I agree that Joan Didion was the most “sensible person in the world.” But it’s not for her common sense. Instead it’s her sensibility—defined in the old-fashioned way as a deep perception of stimuli—and her sensitivity to everything around her.

10.

At the start of her career, Didion played it cool—downplaying the authority of her voice, even as she demonstrated it in sentence after sentence.

And this was still true at the very end. Here is the conclusion of the last interview she gave, shortly before her death at age 87—with its characteristic pessimism, countered by a teasing look at resurrection.

What does it mean to you to be called the voice of your generation?

I don’t have the slightest idea.

How does it feel to be a fashion icon?

I don’t know that I am one.

Is there anything you wish to achieve that you have not?

Figuring out how to work my television.

What are you most looking forward to in 2021?

An Easter party, if it can be given.

You convinced me, I bought one of Joan’s books. Thank you

Thanks for this appreciation of Joan Didion, whose non-fiction in particular I greatly admired when I was younger. One quibble: you write that "she turned into a leading voice in the counterculture." I'm sure what you mean by that, but Didion, as I recall, had little if any sympathy for the counterculture. She was perhaps a leading explicator of the counterculture to those who found it as baffling and disturbing as she did. She wrote certainly not from within the counterculture but from outside it for others who were even further removed from it.