Death: A Literary Guide

Can you really prepare for it or even understand it? These 10 books are my cherished touchstones on the matter

“Death never takes a wise person by surprise.” Or so said French aphorist Jean de La Fontaine.

But how many of us are that wise?

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Some people hate even hearing the word. Writers have learned many ways of referring to death without actually mentioning it. Here’s one of my favorites:

Maybe we should bring that back, and talk more about rewards. That has a happy ring about it. It’s like you belong to a airline loyalty program and have just cashed in all your frequent flyer miles. “Heaven, please—and make it a first class ticket!”

The more deeply you dig into the past, the more unusual the phraseology. So I’m still not quite sure what this headline from an Alabama newspaper is trying to convey. But maybe circumlocutions are necessary when you lose the Civil War.

We’ve gotten more cautious in our obituaries. Nobody is “called home” anymore, in E.T. fashion—at least not in a newspaper writeup. And they certainly don’t “meet their maker.” We opt for more ambiguous phrasing—somebody just left us or passed or is at rest.

But that D word makes us nervous.

So at least a few of you won’t want to read any further than this. But maybe some readers are like me. I’m in no rush to get my reward—I’ll let those frequent flyer miles pile up, thank you very much. But I am absolutely convinced that regular meditation on mortality is psychically beneficial.

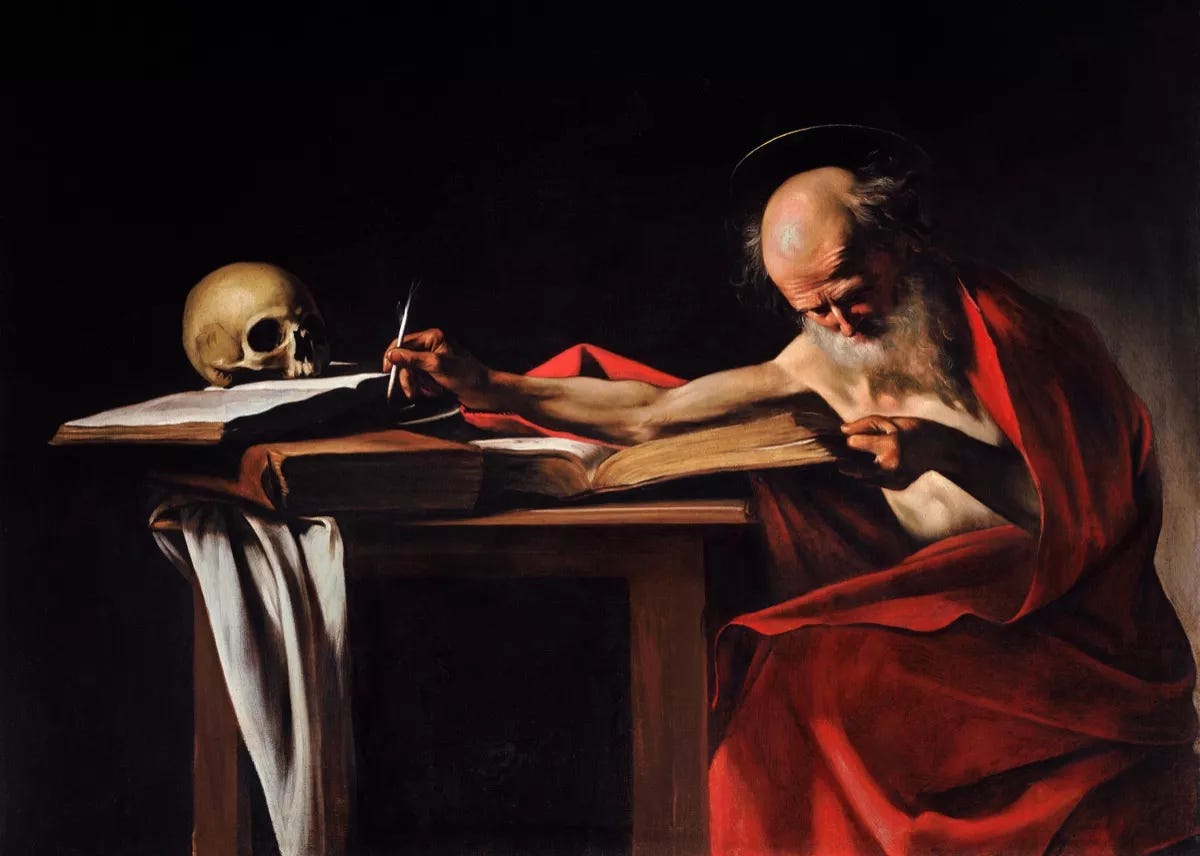

The ancients did that, and called it memento mori—a mulling over mortality, typically one that seeks out some external stimulus (most typically a human skull). We can even trace this practice back to Socrates, who claimed that the purpose of philosophy is the pursuit of death and dying.

That’s a shocking thing to hear—nobody would dare say it in the current day. But Socrates insisted that this led to serenity at the actual time of death. And he proved it in his own final days with a calm tranquility that amazed his students, and even his enemies.

Count me among the believers in memento mori.

I even have a relaxing meditation on the matter. I may share the whole thing with you some day. But the initial step in it is to say the following:

I accept my mortality.

This is actually a very liberating thing to assert. A lot of our anxieties disappear—or are, at least, notably lessened, by accepting our human condition. We battle so much against aging and its inevitable endpoint. But this is like the proverbial old man yelling at the clouds. It’s misplaced energy—an anger without any positive recompense.

I also turn to books for this—but good literary treatments of the subject are extremely rare. After all, who has the Socratic wisdom to grapple with death before the necessary moment arrives?

But here is my literary reading list for death.

Plato: Apology, Crito, and Phaedo

This is the best starting point to understand your own inevitable demise. When my son Thomas was in 7th grade, we put together a summer humanities reading list, and this was his introduction to philosophy (which was later his college major). You might think that a youngster wouldn’t want to read an account of the trial and death of Socrates, but this is one of the most inspiring stories in the whole Western canon. My son loved it, and you will too. If you haven’t read it, you are missing out on one the wisest works ever written.

Herman Hesse: The Glass Bead Game

This book includes a long section that is the best account I’ve ever read about a good death—although I’m sure that some will bristle at the notion that such a thing is possible. And it’s about as non-denominational as they come. I’m referring to the lengthy section of The Glass Bead Game dealing with the final years of the protagonist’s mentor, an old music master. This is as profound as anything I’ve ever read in modern literature about aging and death. I won’t try to paraphrase it—I can’t—but simply suggest you read it, savor it, and learn from it.

Joan Didion: The Year of Magical Thinking

In late 2003, Joan Didion’s world fell apart. Her daughter was in a coma from septic shock, and on December 30 her husband John Gregory Dunne died suddenly shortly after the couple had returned from the hospital. In this stark, confessional book, Didion scrutinizes her own responses in the immediate and longer term aftermath, as she vacillates from intense denial to pragmatic interventions in her day-to-day grieving. This is one of the most honest non-fiction narratives on mourning you will ever read.

Alfred Lord Tennyson: In Memoriam

How far the mighty Tennyson has fallen. In his day, people revered Tennyson’s poetry, and mentioned his name alongside Shakespeare, Chaucer, and Milton. But even college English majors refuse to read him anymore. That’s their loss—he is one of the most musical and moving poets in the English language. And never more so than in this work. After his friend Alfred Henry Hallam died at age 22, Tennyson wrote a 2,916-line poem in 133 sections. In Memoriam is a requiem in words, and the author’s grieving comes across with savage intensity despite the focused control of his iambic tetrameter form.

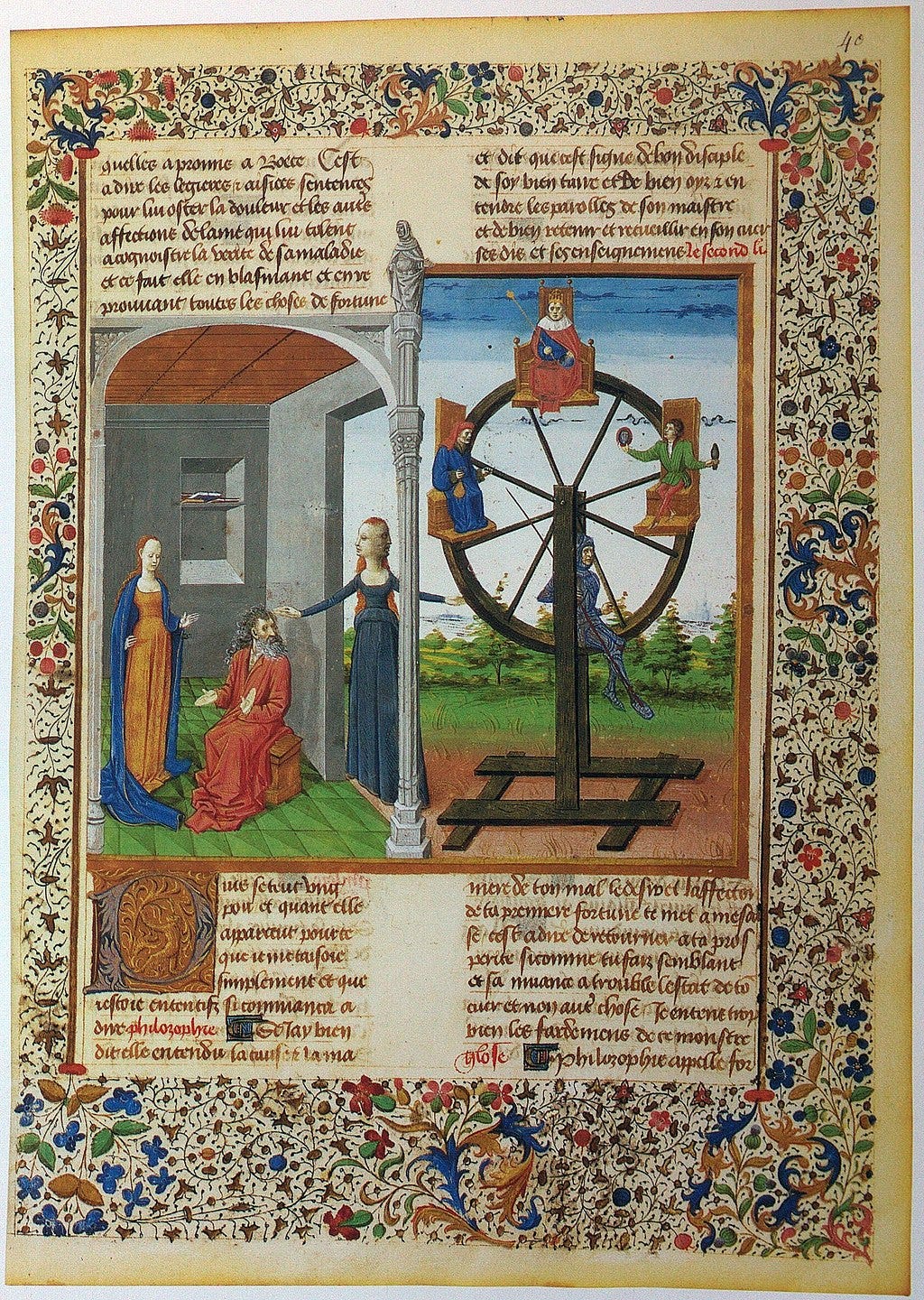

Boethius: The Consolation of Philosophy

In 523 AD, Boethius was imprisoned in Pavia on (probably false) charges of treason, where he waited his eventual execution. He used that opportunity to write this extraordinary work, a thoughtful and tranquil assessment of the human condition and death. Some of this work will remind you of the Socratic narrative above, but there are also elements of stoicism and Christianity here (although some religious authorities were unhappy that Jesus is never mentioned in the text). But no matter what your background or orientation, this work will deliver the consolation promised in its title.

(Addendum for music fans: Boethius also wrote one of the most important medieval works on music—very influential in its time, but less read nowadays than this philosophical work.)

Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love

With each passing year, my own thinking gets more mystical—I’ve come to question many of the parameters of reality I once believed were rock solid, and sometimes I worry what others will think of my increasingly metaphysical worldview. But it is what is, so I make no apologies.

Okay, I still don’t go to fortune tellers or even look at my horoscope. I laugh at the notion of seances and other ways to scam the credulous. But I do read the first-person narratives written by the great mystics of the past. So don’t be surprised to see The Autobiography of a Yogi on my shelf, or The Life of Milearepa, or The Cloud of Unknowing, and other books of this sort. These are thought-provoking works, and reveal a striking convergence among those who have probed these matters in different times and places.

Which brings us to the case of Julian of Norwich (although we’re not even sure that was her actual name).

In the year 1373 AD, she suffered a terrible illness at age 30—and was convinced she would die. But she had visions during this period, and after her recovery felt they needed to be shared with others. Her work Revelations of Divine Love is a classic of spirituality, although if you find mysticism distasteful you should keep away from it. This is about as metaphysical and otherwordly as writing gets.

Leo Tolstoy: The Death of Ivan Ilyich

I admire this book, but it’s so grueling I’m almost afraid to read it again. To Tolstoy’s credit, you can’t say that he avoided the big topics. He wrote the most famous novel about war. He wrote two of the best novels about marriage—not just Anna Karenina, but the even more painfully vivid novella The Kreutzer Sonata. And then we come to The Death of Ivan Ilyich, the story of an esteemed public servant afflicted with a terminal illness and facing his impending death. Like The Kreutzer Sonata, this is a distressing story to read—you almost wish Tolstoy were less probing, less insightful. But he refuses to hold back. The result is the most powerful fictional realization of the memento mori in our literary canon.

Willa Cather: Death Comes for the Archbishop

Death comes from the archbishop, but only at the very end of this story. Yet that’s fitting for a narrative that wants to present a fully integrated panorama of the human condition, with death as not our implacable enemy but the inevitable final stage in a life well-lived. In some ways, the protagonist Bishop Jean Marie Latour is already dead to the world at the outset, when the French prelate is sent to the ends of the earth—or, to be specific, Santa Fe, New Mexico. The story is based on the life (and death) of Jean-Baptiste Lamy (1814-1888), who accepts the call of his vocation in traveling first from France to Ohio, and then on into the Wild West. By the way, this is also one of the best historical novels about American frontier life.

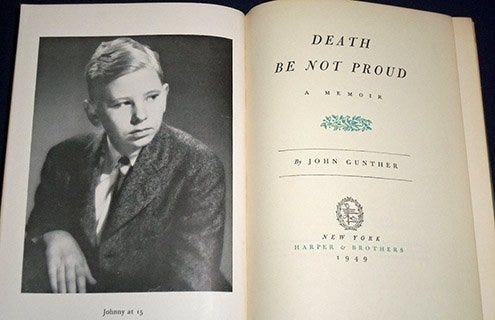

John Gunther: Death Be Not Proud

Gunther was a successful journalist whose life was a charm—until his teenage son Johnny was diagnosed with a brain tumor. For more than a year, the parents tried every possible treatment and stratagem—but with growing despair. Every day, the author sees how is son is drained, exhausted, and suffering—but the youngster continues to work hard in school, and even has hopes of getting into Harvard. This brave teenager somehow manages to get his high school diploma just days before his death in June 1947.

This is one of the most harrowing books you will ever read. Publisher Harper & Row was initially reluctant to release it because it seemed too private, too personal, perhaps even indecent. They later changed their mind, and Death Be Not Proud had a tremendous impact, not just as a lauded literary work, but as the book that (in the words of one commentator) “unleashed American grief.”

Few people read this book nowadays. But that’s a shame—Gunther somehow created, out of his own loss and pain, one of the greatest works of 20th Century American non-fiction.

Hermann Broch: The Death of Virgil

When the Nazis marched into Vienna in 1938, Hermann Broch was immediately arrested, and assumed he would soon be executed as an enemy of Hitler. While imprisoned, he began work on this novel which he believed would be his final work.

I need to warn you upfront that this is an avant-garde book, with dense stream-of-consciousness prose more challenging than Faulkner at his most convoluted, and almost Joycean in its demands. It’s an ambitious novel about a great author on the brink of death—and written by another great author who thought he would soon die.

Honorable Mention: I opted for serious books here, but if I were including comic novels on death, I would start with The Loved One by Evelyn Waugh and Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Gabriel García Márquez. I also excluded investigative journalism along the lines of The American Way of Death by Jessica Mitford—but I highly reccomend it for Mitford’s unsurpassed exposé of the funeral business. A Grief Observed by C.S. Lewis is also an acknowledged classic of spiritual literature, and worth reading. I also considered adding Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, another ambitious novel in the same vein as Broch’s work. (I plan to write about it at a later date.) Finally, here’s a very deep recent essay on death that draws on surprising insights from hospice doctors and nurses.

Several things come to mind as I've just reached my seventies. Much harder than contemplating my own death is that of my loved ones - my wife, our cats, members of my extended family and close friends. Keeping in mind that some day I will no longer be here is a very beneficial exercise for me as it daily reminds me to savor and enjoy the wonderful simple things in my life while I am still alive that would be so easy to take for granted - the smell of freshly cooked food, the feel of water on my lips, the wind on my face, the amazing ability to still walk without pain and even play sports, the routines of taking out the garbage, brushing my teeth, making music with friends, enjoying the sound of my wife’s voice while she’s talking to me, the warmth of my cat on my lap. When I was in my 30s or 40s, the idea of 10, 20, 30 years hence was merely idle speculation but now it is very possible I may indeed never get there. And given that subjective time has really sped up as I’ve aged it becomes all the more sobering.

After much contemplation of death I’ve come to believe that we don’t disappear but that we simply are transformed into a different being of a type that is completely beyond our ability to comprehend hence not worth worrying about while I’m alive, sort of like a raindrop that falls into a pond or the ocean. How could that single drop ever comprehend what becomes of it as it completes its fall? It doesn’t cease to be water but it has entered a new realm entirely. Add to the fact that when we were born we had no idea what was happening to us and don’t have the slightest recall of whence we came. I’m not religious at all but I don’t see how any of that would conflict with serious religious teachings.

For now I conceive of death as being similar to being asleep. Every time I drift off at night I accept that I will completely lose control of what I will experience in my dreams and even more so when I reach deep sleep and effectively everything no longer exists for me. Maybe sleep is nature’s kind way to remind us of our coming death on a daily basis.

Some very helpful recommendations. I’d add Jung to the mix since much of his practice was preparing men and women in their twilight years for their death.

“Only if we know that the thing which truly matters is the infinite can we avoid fixing our interest upon futilities and upon all kinds of goals which are not of real importance.” - C.G. Jung