The Rise and Fall of Hunter S. Thompson (Part 1 of 3)

Below is the first installment of my three-part essay on Hunter Thompson. This is the latest in an ongoing series of essays on counterculture figures—including (so far) Jack Kerouac, Frank Zappa, Bob Dylan, Joan Didion, Eden Ahbez, and Gregory Bateson.

At some point these may appear in a book on the counterculture. But right now they are only available here on The Honest Broker.

Please support my work—by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

The Rise and Fall of Hunter Thompson (Part 1 of 3)

By Ted Gioia

I.

Hunter Thompson’s first run-in with the FBI happened at age 9.

One day in the summer of 1946, two federal agents knocked on the door of the Thompson home in the Louisville suburbs much to the surprise of the adult residents. Here they threatened the tiny future Gonzo King, who had just finished third grade, with a 5-year prison term for destroying federal government property—which the boy had done, and much more.

Not only did little Hunter topple a mailbox, using an ingenious set of ropes and pulleys, but he had sent it flying into the street in front of an oncoming bus. Of course, he had his reasons—he always did.

Thompson didn’t like the bus driver, who was “rude and impatient.” When youngsters arrived a few seconds late, and ran after the bus, the driver refused to stop. Most kids put up with such petty injustices, but little Hunter Thompson decided to do something about it—setting a pattern that would last the rest of his days.

Another two decades would elapse before Thompson invented Gonzo journalism—that immersive style of reportage that puts the writer at the center of the story. But young Hunter had already figured out the basic formula:

He caused the news;

Things got destroyed;

Authorities didn’t like it.

Of course, people (typically criminals and revolutionaries) had done all this before Hunter Thompson. But he turned it into a journalism career.

How far could he push it? Thompson would eventually find out—with the assistance of savvy editors such as Warren Hinckle at Scanlan’s and Jann Wenner at Rolling Stone. But he got even more fuel from drugs, alcohol, and a generous expense account, as well as the various cronies and sidekicks who accompanied him on his frantic journeys into the wounded heart of late 20th century America.

Back at age nine, fast talking by father and son, assisted by tears from mom, got the boy off the hook. But more arrests ensued. In high school, Thompson was taken out of a classroom in handcuffs by police—this time for a bout of underage drinking followed by vandalism. A short while later, he got caught up in a (possibly armed) robbery, and spent thirty days in jail.

He missed his high school graduation as a result, and was thrown out of Louisville’s Athenaeum. The latter was especially painful, because the Athenaeum was not just an elite club for partying, but a genuine literary society. For a better adjusted young man, this connection might have been a step toward an Ivy League degree, but Hunter S. Thompson was not that kind of young man.

Heaven knows, his parents tried. Thompson’s mother, in particular, had a firm sense of Southern gentility, and raised her son in that spirit. His dad, who sold insurance, could hardly have provided a stronger role model for conformity and civic responsibility. But their kid was a devil—he even painted the gates to hell on the floor of his bedroom.

Give the boy some credit, he was a creative little devil. But if dealing with him was hell, it soon got worse when he earned a driver’s license. That’s when Thompson became hell on wheels.

His stint in Hells Angels was still in a dim distant future, but the Gonzo kid was already prepping for it back in Louisville. Thompson constructed his first ‘automobile’—made from a crate, three wheels, and a washing machine motor. Hunter’s mother relented and gave him the keys to her car, if only to prevent her son from driving in a death trap like this. But that was really the proverbial attempt to find the lesser of two evils. In time, Thompson proved he could do damage on anything that moved.

Over the years, Thompson tried to lose that license in almost every conceivable way. As early as 1958, a friend who visited Hunter in Greenwich Village noted that he had accumulated 122 parking tickets. A few years later, Thompson spent the advance he received for his Hells Angels book on a motorcycle—and was promptly arrested three times in the next three weeks.

He got so many citations in subsequent months, that his California driver’s license would have been revoked, except for his constant posting of bail money and “a never-ending involvement with judges, bailiffs, cops, and lawyers, who kept telling me the cause was lost.” But he managed to prevail, only to spinout in an epic motorcycle crash on a wet road north of Oakland.

Even Thompson had a hunch he would die on the road some day, and seemed more surprised than anybody it never happened. His edict on this chronic risk-taking captures the author’s worldview in a single epigrammatic sentence: “Being shot out of a cannon will always be better than being squeezed out of a tube”

But motorcycle escapades were still in the future in those Louisville days. At the conclusion of his jail sentence, Thompson took a much more conventional journey—to Scott Air Force Base near Belleville, Illinois for basic training.

This seems odd. Why would Hunter S. Thompson, an individualist with anarchic tendencies, join the military? But what other options did he have? He was certainly smart enough for college and legitimately belonged in the Ivy League, where many of his high school friends were heading, but his criminal record scared off those institutions. Even the Army put him on hold, so Thompson signed up with the Air Force by default.

He didn’t last long, and was lucky to get out with an honorable discharge. But even better was the experience he gained writing for a military newspaper. He parlayed this into a civilian newspaper job in Pennsylvania, also short-lived—he literally had to escape at a moment’s notice after trashing a coworker’s car, not even collecting his last paycheck.

Thompson’s next stop was New York, where he was down to his last five bucks when Time magazine took him on at the lowest possible level, namely copyboy. But the Time stint also ended quickly and unhappily—as did almost every other Hunter Thompson endeavor in those days. He had an instinct for infuriating almost everyone in his path, which strangely enough also brought him a growing cadre of friends even as he got fired, booted out, chased away, or exiled from place after place.

II.

I’m certain he learned a few writing skills in these come-and-go jobs, but the real story of how Hunter Thompson developed his prose style is much odder—and far more methodical than anybody realized.

That’s because there were always two Hunter Thompsons. One was crazy mad about everything, flying high on adrenalin (combined with various other chemicals), and destroying as much as he created. But there was a different Hunter, unseen by the public, and this alter ego was disciplined and ruthlessly organized—a veritable Clark Kent of the journalism trade, hidden behind a more flamboyant Gonzo Superman.

This hidden Hunter refined his writing chops by typing out The Great Gatsby and A Farewell to Arms. “Your hands don’t want to do their words—but you’re learning,” he later explained.

When friends laughed at this technique, he defended it in almost mystical terms: “I just want to feel what it feels like to write that well.” Along the way, he was internalizing the texts as he recreated them, page after page. In the aftermath, Hunter S. Thompson gradually emerged as a true heir to Hemingway and Fitzgerald, taking his place as one of the great American prose stylists of the century.

No MFA program or writing teacher would ever ask students to do this rote typing. Not because it doesn’t work—I suspect that it does—but simply because who has the patience to learn in such a painstaking, arduous way?

Hunter Thompson did.

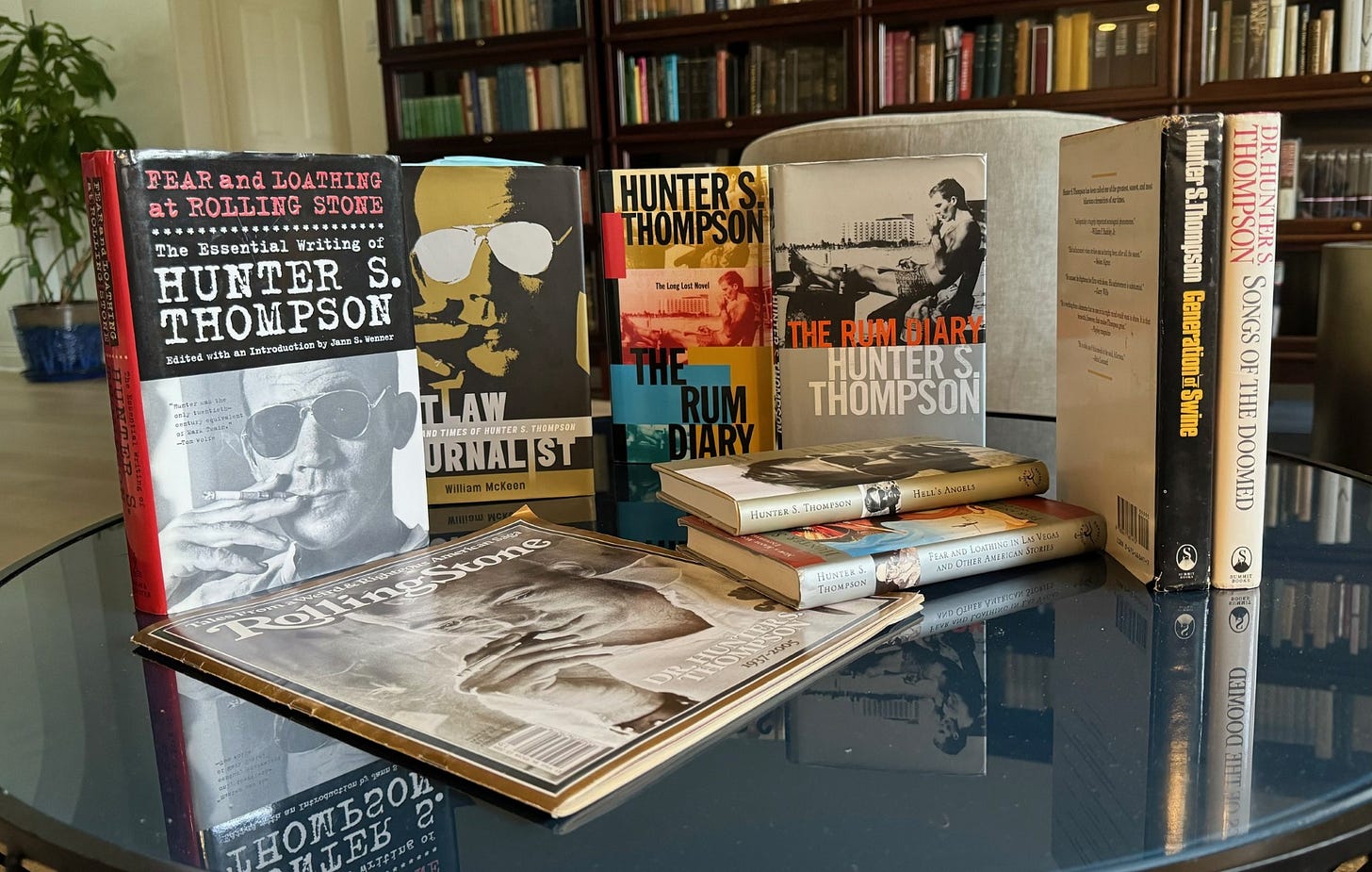

You can’t argue with the end results. Critics have leveled many charges against Hunter Thompson, and he’s guilty of almost every one. But you can’t dismiss the energy of his prose, the sweep of his sentences, or the transgressive power of his persona as it radiates from the printed page. Even when he is out of control, he somehow writes taut, unforgettable words.

I once heard somebody say that Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas doesn’t have a single sentence or word that a reader would want to change. And it’s true.

Here’s the opening—and I say, without the slightest exaggeration, that this is writing that changed the whole rulebook for American non-fiction prose:

We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold. I remember saying something like “I feel a bit lightheaded; maybe you should drive....” And suddenly there was a terrible roar all around us and the sky was full of what looked like huge bats, all swooping and screeching and diving around the car, which was going about a hundred miles an hour with the top down to Las Vegas. And a voice was screaming: “Holy Jesus! What are these goddamn animals?''

Then it was quiet again. My attorney had taken his shirt off and was pouring beer on his chest, to facilitate the tanning process. “What the hell are you yelling about?'' he muttered, staring up at the sun with his eyes closed and covered with wraparound Spanish sunglasses. “Never mind,” I said. “It's your turn to drive.” I hit the brakes and aimed the Great Red Shark toward the shoulder of the highway. No point mentioning those bats, I thought. The poor bastard will see them soon enough.

It was almost noon, and we still had more than a hundred miles to go. They would be tough miles. Very soon, I knew, we would both be completely twisted, but there was no going back, and no time to rest. We would have to ride it out….

And it continues like that, immersive and irresistible, for the next two hundred pages. Nobody had written like that before—not Kerouac or Kesey, Mailer or Miller, Wolfe or Wolfe or even Woolf.

That’s Hunter Thompson. There’s always someone in control behind the wheel—even when he seems most out of control.

This hidden discipline showed up in other ways. Years later, when he ran for sheriff in Aspen or showed up in Washington, D.C. to cover an election for Rolling Stone, savvy observers soon grasped that Thompson had better instincts and organizational skills than some of the most high-powered political operatives. People rallied around him—he was always the ringleader, even going back to his rowdy childhood. And hidden behind the stoned Gonzo exterior was an ambitious strategist who could play a long term game even as he wagered extravagantly on each spin of the roulette wheel that was his life.

“I don’t think you have any idea who Hunter S. Thompson is when he drops the role of court jester,” he wrote to Kraig Juenger, a 34-year-old married woman with whom he had an affair at age 18. “First, I do not live from orgy to orgy, as I might have made you believe. I drink much less than most people think, and I think much more than most people believe.”

“I drink much less than most people think, and I think much more than most people believe.”

That wasn’t just posturing. It had to be true, merely judging by how well-read and au courant Thompson became long before his rise to fame. “His bedroom was lined with books,” later recalled his friend Ralston Steenrod, who went on to major in English at Princeton. “Where I would go home and go to sleep, Hunter would go home and read.” Another friend who went to Yale admitted that Thompson “was probably better read than any of us.”

Did he really come home from drinking binges, and open up a book? It’s hard to believe, but somehow he gave himself a world class education even while living on the bleeding edge. And in later years, Thompson proved it. When it came to literary matters, he simply knew more than most of his editors, who could boast of illustrious degrees Thompson lacked. And when covering some new subject he didn’t know, he learned fast and without slowing down a beat.

But Thompson had another unusual source of inspiration he used in creating his unique prose style. It came from writing letters, which he did constantly and crazily—sending them to friends, lovers, famous people, and total strangers. Almost from the start, he knew this was the engine room for his career; that’s why he always kept copies, even in the early days when that required messy carbon paper in the typewriter. Here in the epistolary medium he found his true authorial voice, as well as his favorite and only subject: himself.

But putting so much sound and fury into his letters came at a cost. For years, Thompson submitted articles that got rejected by newspapers and magazines—and the unhinged, brutally honest cover letters that accompanied them didn’t help. He would insult the editor, and even himself, pointing out the flaws in his own writing and character as part of his pitch.

What was he thinking? You can’t get writing gigs, or any gigs, with that kind of attitude. Except if those cover letters are so brilliant that the editor can’t put them down. And over time, his articles started resembling those feverish cover letters—a process unique in the history of literature, as far as I can tell.

When Thompson finally got his breakout job as Latin American correspondent for the National Observer (a sister publication to the Wall Street Journal in those days), he would always submit articles to editor Clifford Ridley along with a profane and unexpurgated cover letter that was often more entertaining than the story. In an extraordinary move, the newspaper actually published extracts from these cover letters as a newspaper feature.

If you’re looking for a turning point, this is it. Thompson now had the recipe, and it involved three conceptual breakthroughs:

The story behind the story is the real story.

The writer is now the hero of each episode.

All this gets written in the style of a personal communication to the reader of the real, dirty inside stuff—straight, with no holds barred.

Why can’t you write journalism like this? In fact, a whole generation learned to do just that, mostly by imitating Hunter S. Thompson….

Click here for part two of “The Rise and Fall of Hunter S. Thompson”

Here is my one Hunter story. From a column about him at National Review.

Sometime around 1990 Hunter and Jann Wenner, founder and editor-in-chief of Rolling Stone, were invited to speak at Columbia University. I sensed at that time that Hunter was on the downward slide and this could be his last hurrah and so I agree to tag along. I decide at the top of the evening to stay until the end of the end wherever that might lead.

Our small group meets in the green room at Columbia. We stand around slugging from a bottle of Chivas Regal. Around and around the bottle goes. Of course, Hunter is well ahead of us, having started much earlier. We stumble upstairs for the speech.

The hall is filled to the rafters, I mean absolutely filled. Hunter and Jann sit at a table center stage. Hunter slurs and slurs, and slugs from the Chivas and hacks up oranges with a huge machete. At one point Jann, wearing natty French cuffs, is lustily booed for being a corporate sell out. Hunter keeps passing the only bottle of scotch through the stage curtain to those of us backstage. “Speech” over, we head cross town to Elaine’s, the longtime watering hole of New York writers and Hollywood outriders.

Keeping with my pledge to ride this pony right down to the ground, I plant myself right next to Hunter at our table of now about ten. We are all pretty drunk, but Hunter is wasted. Still he orders about five courses and eats every morsel. He even eats all the bread, which he heavily butters and covers with pepper. I try to engage him in conversation and I swear hardly the only words I understand are “Nixon,” “Peru,” and “acid.” Along with everything else, Hunter is tripping.

At one point Hunter leans over to me and says something on the order that he is going to the bathroom and there is a guy staring at him from the bar and that I am to watch his back. “Errrr, O.K., Hunter.” Hunter gets up and heads to the men’s room, Jann follows him and sure enough the guy at the bar gets up and follows them both. I join the parade and when I round the turn I see this: The guy from the bar is leaning his full weight on the men’s room door, bending it so far back I can see Jann understandably cowering inside. So, I grab the guy and pull him away from the door and back down the hallway. The whole bar descends on the cacophony in that tight little hallway; bartenders, waiters, patrons. Hunter comes out of the men’s room, comes up to the guy and the guy says this, really loud; “I just wanted to get stoned with you, man.”

The hallway clears, they take the guy back to the bar (they don’t toss him out; Elaine’s is a remarkably forgiving place), and Hunter grabs me and pulls me into the lady’s room whereupon he pulls out a huge bag of cocaine. “It’s not very good,” he says, “but there is a lot of it.” Thankfully, almost immediately Tommy-the-good-bartender yanks us out of the lady’s room and puts us back at our table.

I do not remember much of the rest of the evening except that I am the last one to clear out; well, me, Hunter, and his “secretary.” It is the weeist of hours. Hunter’s limousine takes us downtown. He pulls up somewhere on Central Park South. Hunter gets out and weaves along the sidewalk, scotch bottle in one hand, “secretary” in the other. I yell out to him, “Hunter, where are you going?” “Take the limo,” he says, “He’ll take you wherever you want to go…”

I slump against the window as the car takes me the few blocks to my Upper West Side apartment. The morning joggers are jogging. People are walking briskly to work. The trash trucks are making that beeping sound that is joyful first thing in the morning but deeply depressing at the end of night. One cannot do this thing too many times or for too long and Hunter did both, and now he has a bullet in his brain.

Requiescat in pace, dude.

Beneath the surface froth of both Thompson and Trump I can’t help feeling that their personalities are very similar. Needless to say Thompson had more skill as a writer, but in his own awful way Trump is an effective writer. Both left a trail of destruction behind them that overturned the established order. Arguably, Thompson created something new and valuable in both the literary and philosophical terrains, but there are those who think that true of Trump. Not that I’m one of them I hasten to add. But if one adheres to the “move fast and break things” concept that has become so popular among certain types, one might consider Thompson to be the progenitor of Trump. It’s curious how apparent opposites can share so many attributes.