Why Do Heroes Always Have Theme Songs (Part 1 of 3)

An excerpt from my new book 'Music to Raise the Dead'

I have a lot of extreme ideas about music.

You can probably tell just by looking at the title of my new book: Music to Raise the Dead—which is currently available only on The Honest Broker.

In my worldview, conductors take charge of things much larger than an orchestra—that little stick they hold was originally a magic wand. Their songs are supposed to heal, to sanctify, to empower, to transform….and even to destroy.

That’s my kind of musicology. Along the way, I insist that musicians created the first legal codes. And musicians laid the groundwork for philosophy. And did many other things on the largest scale imaginable—preserving history, codifying knowledge, and interceding with the divine.

I back up these claims with lots of evidence, drawn from three decades of research. At each step I try to show that my vision of empowered music is connected to the larger role songs play in vibrant societies and human flourishing.

But a core claim at the center of my book is that musicians show us how to be heroes. Songs help us navigate our most dangerous journeys and milestone moments—much like all those gimmicky devices that James Bond uses, or those Indiana Jones stunts.

Can songs really do that? Read on and find out.

But before jumping into the narrative, let me provide the table of contents for the entire book—with links to the sections I’ve already published.

Each chapter answers a single question.

You can read the chapters in isolation, without tackling the entire book. That’s true of the section I’m publishing today. But if you want to follow the whole story in sequence, here are the links to do it.

MUSIC TO RAISE THE DEAD: The Secret Origins of Musicology

Table of Contents

Prologue

Introduction: The Hero with a Thousand Songs

Why Is the Oldest Book in Europe a Work of Music Criticism? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Is There a Science of Musical Transformation in Human Life? (Part 1) (Part 2)

What Did Robert Johnson Encounter at the Crossroads? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Why Do Heroes Always Have Theme Songs? (Part 1) (Part 2) (Part 3)

What Is Really Inside the Briefcase in Pulp Fiction? (Part 1) (Part 2)

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Why Do Heroes Always Have Theme Songs? (Part 1 of 3)

By Ted Gioia

I’ve written a lot about heroes here—much more than you will find in any other music book. But the heroes in these pages don’t resemble Tom Cruise or Harrison Ford or the other good-looking protagonists strutting and preening in Hollywood movies. Or in video games, comic books, TV shows and other media products of contemporary consumer culture.

Instead of facing dangers with a gun or sword, my heroes rely on music, rhythm, and poetry. They take on great risks, but not for conquest or treasure, instead seeking personal transformation and wisdom.

They embark on their dangerous missions without weapons. If they carry a bow, it’s a musical bow, not one that shoots arrows. Instead of flying Han Solo’s spaceship, they rely on a drum to initiate their journeys. If they carry a wand, it isn’t Harry Potter’s type, but more like a conductor’s wand or the laurel staff of the ancient bards.

They are heroes with songs.

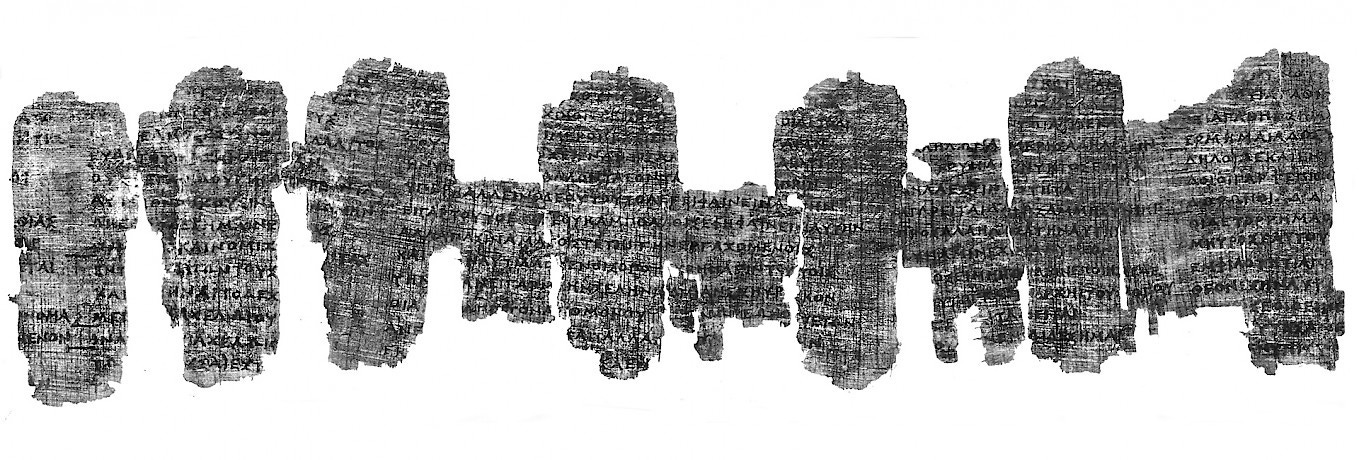

This would all seem absurd if we hadn’t already accumulated so much evidence, from so many time periods and every region of the world, to substantiate this alternative view. The patient reader who has traveled so far in this book has now seen how heroism was originally a musical tradition. Musicians sang about heroes (Homer, for example), and were heroes themselves (shamans, for example), and they taught others how to achieve great things (as demonstrated, for example, in the Derveni payrus, the oldest book in Europe).

And this happened everywhere in the world.

This ancient tradition of heroic music-making is marginalized or forgotten in the current day. We prefer weaponized heroes with lots of CGI. But, as we shall see, the entertainment industry cannot dispense with the traditional heroic quest and its music, no matter how unsuitable this playbook might be for cinematic treatment. Even fake movie heroes require heroic songs—we will hear some of them below.

But how do actual musicians get turned into movie heroes? Let’s look at one example.

Consider the case of Myrddin Wyllt, a prophet and bard whose songs were heard in Carmarthen in South Wales almost 1500 years ago. He is our classic shaman, who consulted with animals—they might be called totems or tutelary spirits in other contexts. But he was also a famous warrior.

A passage in Annales Cambriae mentions how this mysterious figure went mad at the Battle of Arfderydd in the year 573 AD. His madness was probably a kind of possession or trance, or what Mircea Eliade calls, in his study of shamanism, an “archaic technique of ecstasy.” After this decisive moment, Myrddin Wyllt went on a journey into the wild woods—his last name actually translates as “wild”— where he composed inspired works of bardic lore, a few lines of which have survived to the modern day.

Why should we care about Myrddin Wyllt?

Well, just look at his legacy, and consider its impact. In the early twelfth century, Geoffrey of Monmouth used Myrddin as a blueprint in constructing his semi-historical account of Merlinus Ambrosius. By the time we arrive at Sir Thomas Mallory’s Le Morte d'Arthur (1485)—in my opinion, the most influential prototype of the modern adventure story—this shadowy figure is simply known as Merlin, and he demonstrates awesome powers as a magician, sage, and guide for King Arthur.

Today, Merlin is more than a character, he’s actually a meme or pop culture archetype, appearing not just in books and films, but also video games, cartoons, comic books, and almost any other type of fantasy narrative you can name, from Japanese manga to BBC miniseries. But he started out as Myrddin Wyllt, a prophetic bard known for his mastery of altered mind states—or, in other words, a musical master of the vision quest.

Merlin’s influence is hardly limited to stories about King Arthur. He has served as role model for every wise sage with special powers in pop culture, a stock figure found in action and adventure movies of all genres. He is the antecedent of Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings, Yoda in the Star Wars universe, and Dumbledore in the Harry Potter stories.

Even if you don’t have magic in the story, you still need a Merlin figure—so he transforms himself into the spy masterminds Q and M in the James Bond films, or those wrinkled, ancient martial arts masters in a thousand karate and kung-fu movies, or in some other formulaic guise. Of course, there’s still a kind of magic here: a special high-tech gadget for 007’s use, or an esoteric fighting technique, or some other top secret assistance for the hero to use on the journey.

In the original version, those were all songs. But not just ordinary songs—this music possessed uncanny power.

All this started with a powerful shaman named Myrddin, but these current-day imitators have mostly forgotten their music. Agent Q does not share magical songs with James Bond, nor do any of these other Hollywood stick figures demonstrate the slightest musical ability. Even so, they are still conductors, similar to those we studied back in chapter two.

In the case of wizards such as Gandalf or Dumbledore they actually retain possession of a wand, a symbol rich in magical and musical resonances. But it is no longer the laurel staff given by the Muses to Hesiod the bard, or the stick you wave to set the New York Philharmonic into motion. It demands respect as a physical object that now contains the shaman’s musical magic in reified form—a significant displacement that we will witness in other settings in the pages ahead.

All this is a degraded form of the actual quest. But the biggest letdown is the threadbare wisdom conveyed by these modern-day conductors of the hero’s journey. They invariably make their appearance midway through the movie, and spout off advice that is more trivial than the worst self-help manual.

It’s hard not to laugh when you hear cheesy hero’s aphorisms such as “Be like water” or “Resist the Dark Side, Luke Skywalker!” The fact that scriptwriters still need to enlist such paltry sages for their brief moment on the stage tells us how deeply embedded these shamans are in our psyches, and how reluctant we are to abandon their guidance. Yet how sad to witness a tradition that gave birth to great spiritual and mythic traditions around the world and spurred the rise of Western philosophy reduced to such inanities.

I am disappointed that these movie magi no longer have powerful songs to share with the film’s protagonist. And, at first glance, it might seem that heroes nowadays do their jobs without the help of any supporting music. But that’s not true at all.

Every screen hero has a theme song, and these possess remarkable staying power. The iconic theme composed for super-spy James Bond in his first film appearance in 1962 is still propelling the franchise forward more than sixty years later. The multibillion dollar Mission Impossible franchise absolutely requires the incantatory appearance of the familiar 5/4 theme song launched with the original TV show back in 1966, which hasn’t lost its mojo despite a half-century of changing musical trends and tastes. Indiana Jones and Harry Potter enjoy endless reboots in movies, games, and TV shows—but the audience would refuse to accept these brand extensions without these heroes’ special songs.

Strange as it may seem, the songs have actually proven more enduring than the actors, plots, directors, or settings in these films. This runs against everything we’re told about the music business, where an instrumental track from 1962 would have very little significance in any other sphere of pop culture. But when it comes to heroes, different rules apply. These larger-than-life figures need their special songs and—as in the traditional quest stories—the melodies that have proven their magic in the past are the most potent of all.

Even so, it’s worth stressing that a tremendous amount of effort has gone into depriving heroes of their music. This project has been underway for more than two thousand years. We saw in the previous chapter how the songs that supported ancient laws and legal codes were eliminated by later jurists—who not only jettisoned these magical melodies, but did so proudly, looking down on the oral/aural origins of their vocation. And this devaluing of music has been just as visible in a host of other fields and disciplines.

Doctors have learned to heal without their songs, once so central to their craft (although the music is now returning in the operating room, where most surgeons today work with a playlist). Manual laborers have learned to get every job done, no matter how difficult, without the assistance of work songs (but they still prefer to have the radio blasting while they toil). Sailors no longer know their shanties; street vendors no longer sing out the products they offer for sale; union members no longer join their voices together to belt out their solidarity anthems.

Even sex workers—who once were essentially musical performers, believe it or not, in almost every culture—no longer have their special songs to entice and titillate. The last holdouts in this disenchantment of the modern world are spiritual leaders and religious functionaries of all denominations. They retain their holy songs with vehemence, making no apologies for their metaphysical claims, which in other settings are now viewed with such embarrassment.

So we shouldn’t be surprised that the heroes in our stories have struggled to hold on to their empowering music. The first onslaught took place in ancient times. The Romans put enormous energy into turning the epic and lyric and other music genres into literary formulas. In ancient Greece, Homer sang about his heroes, but when the poet Virgil adapted this tradition for the Roman Empire, he operated as an author, not a singer.

In a culture where everybody knew songs, but only a few people could read texts, this shift to the written word added to the elitism and authority of powerful insiders—in fact, the very word author has the same Latin root as the term authority. In his authoritative works, Virgil engaged in a kind of highbrow playacting—pretending to be a singing shepherd in his pastoral Eclogues, or singing advice about farming in his Georgics, or starting out his epic the Aeneid with the famous boast Arma virumque cano ("Of arms and the man I sing"). But he really didn’t want to sing any of these works, which were intended for reading, or perhaps recitation, but not actual bardic performance.

If you trust conventional accounts, you might believe that Virgil set the model for all future narratives about heroes—who were now characters in literary works, not protagonists in powerful songs. But, in fact, the opposite was true. As soon as you left the highbrow world of Roman Imperial culture behind, heroes still flourished in a world of magical songs. And these songs, although marginalized and despised by elites, would come to exert more influence on later heroic narratives than anything concocted by Virgil and his classical cohorts.

Everywhere in Europe, folk ballads preserved this older tradition, and it flourished over the course of centuries, building its appeal on sung tales about heroes, romance, and adventure. These songs reached an audience far larger than anything Virgil could have dreamed of, spanning a territory wider than the Roman empire at its peak, and possessing a vitality that kept heroic music in circulation until modern times.

Yet I was never taught about these folk ballads in college, even though I was an English major specializing in the Western narrative tradition. By any reasonable measure, they should have been a central focus of my education—after all, these were the stories that permeated every nook and cranny of England, as well as the rest of Europe, known to millions who lacked the education to read a Roman epic, or even a tale in their own vernacular script. But they all knew songs about heroes, beguiling stories chanted or sung by the elders in their communities, and handed down from generation to generation.

If you haven’t spent much time studying old folk ballads, you might be surprised by what you find in them. Conventional wisdom tells us that these were the authentic artistic expressions of the common people–or the Volk, as they were called by Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), the German thinker who played a key role in legitimizing this music as an object of scholarly concern. But when I undertook a statistical analysis of hundreds of these ballads, I found that 55% of them dealt with nobility—knights and their lovely ladies, chivalry and feudal splendor, and other trappings of the ruling class.

At first glance, this defies common sense. Why would the Volk (or folk)—many of them peasants living in abject poverty—care so much about the heroic deeds of the rich and powerful? But this all makes perfect sense when you realize that these folk ballads were a continuation of the traditions started by bardic court poets more than a thousand years earlier. Just like these bards, the folk singers sang the praises of elite warrior heroes.

An even more prevalent theme in the folk ballad tradition is magic and the supernatural. My analysis of the canonic Child Ballads—named after Francis James Child, the Harvard professor who collected and published these old story songs during the second half of the nineteenth century—found that 61% of them involve some supernatural or miraculous occurrence. This too is an important historical legacy, and allows us to trace connections between these songs and the shamanistic tradition, where music was inextricably linked with uncanny powers.

The fact that these songs of heroes and magic still flourished in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century is extremely revealing. The literary experts of that period would have told you that the narrative tradition in the modern age had no connection to magic and music.

The most influential literary currents of those years were realism, naturalism, and various experimental schools. The authorities who presided over these exciting movements in elite culture had no interest in the old-fashioned heroes celebrated by their ancestors. The naïve notion of the feudal hero had been undermined back in the early days of the novel, or so you were told, when Cervantes mocked its pretensions in his classic work Don Quixote. And Shakespeare’s most famous knight was the buffoonish Sir John Falstaff—another sly deconstruction of outdated heroic concepts. According to this conventional view of literary history, songs and stories about traditional heroes became little more than a joke around the year 1600.

This whole attitude towards the literary narrative deserves scrutiny—and if examined carefully will be found wanting in many respects. But a revisionist account of literary history is beyond the scope of this book. Even so, we do need to consider the debunked traditional hero, supposedly exiled from the literary world by the great novelists. And even a cursory look at book sales proves that these old-fashioned heroes never died, merely changed genres. Literary critics might praise Flaubert, Tolstoy, Conrad, and Joyce, but the same period in which these highbrow authors operated also saw the rise of a huge mainstream market for genre tales, in which the traditional formulas of the hero’s journey continued unabated.

You could even make the case that every major category of genre fiction has its origins in the ancient songs of the heroes, with their adventures, romances, and magical dealings. Certainly the science fiction genre comes straight out of the hero’s journey formula. The connection is so powerful that sci-fi pioneers Jules Verne and H.G. Wells built the majority of their bestselling novels out of stories that explicitly promise a risky hero’s journey in the title of the book:

Journey to the Center of the Earth,

The First Men in the Moon,

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea,

Five Weeks in a Balloon,

From the Earth to the Moon,

Around the World in Eighty Days,

The Island of Dr. Moreau, etc.

And the fantasy genre is even more explicit in its connections to the sung stories of heroes—Tolkien and his heirs openly imitate those ancient and medieval bardic narratives. The romance, for its part, genre still struggles to escape the clichés of knights in shining armor, although in modern stories the hero’s armor is often replaced by a doctor’s white coat, a soldier’s uniform, or some other garb associated with valor and high performance under pressure. And the horror and mystery genres also show profound connections to the ancient tales of magical, mystical doings.

It would take an entire book to tease out these connections, but for our purposes we can cut to the chase: highbrow literature fought the hero, but the hero won—albeit in the genre sections of the bookstore.

Musicians, those grand heroic journeyers to the Underworld (like Orpheus) or elsewhere, served as prototypes for each of these current day heroes. And, if you pay close attention, you will find that these protagonists still rely on songs, even in the 21st century….

Click here for part two of “Why Do Heroes Always Have Theme Songs?”

Fascinating! Perhaps this is touched upon more in part two, but I couldn’t help but ponder the impact motion pictures had on music and the hero’s tale. Lyrics became expendable and even unnecessary as silent films became “talkies.” Modern heroic theme songs / scores are instrumentals that are the backdrop to dialogue and visual eye candy.

Star Wars and Lord of The Rings being two of my favorites.

For me, the most emotional always had lyrics to some degree or another:

Gonna Fly Now (Rocky)

Footloose (Footloose)

Somewhere Over The Rainbow (Wizard of Oz, talk about magic and the hero’s journey!)

Nobody Does It Better (The Spy Who Loved Me)

Stayin’ Alive (Saturday Night Fever)

Circle of Life (Lion King)

We Don’t Need Another Hero (Mad Max Beyond The Thunderdome)

Tomorrow (Annie, stage to screen)

Conversely, you have anti-hero or villain theme songs that are just as powerful— did the bards partake in these delightfully chilling tales?

Jaws theme

The Emperial March (Star Wars)

The Ballad of Sweeney Todd (stage to screen!)

Poor Unfortunate Souls (Little Mermaid)

I Want It Now (Charlie and The Chocolate Factory)

What an entertaining and enthralling topic to shed light on. Thank you!

It's a powerful thesis, verified by genes. Human speech is shared with birds, who use it specifically as heroic theme songs.

http://polistrasmill.blogspot.com/2019/04/bipedal-bugles.html

Work songs still pop out naturally in some circumstances!

http://polistrasmill.blogspot.com/2021/03/john-henry-20.html

And vendor songs aren't entirely dead either.

http://polistrasmill.blogspot.com/2011/05/crossing-song.html

This song did disappear after I wrote the above piece, when the school switched to an all-digital announcement system with outdoor speakers. Now it's just a beep.