How We Lost the Ability to Listen

In this extract from my book 'Music to Raise the Dead' I look at how texts replaced songs as sources of wisdom and guidance

Today I’m sharing a new section from my book Music to Raise the Dead. I’m publishing it in installments, and it’s currently available only on Substack.

Each chapter addresses a separate question, and can be read as a stand-alone essay.

If you want to read the book in its entirety (or dig into previous sections), I’m sharing the links below.

MUSIC TO RAISE THE DEAD: The Secret Origins of Musicology

Interactive Table of Contents

Prologue

Introduction The Hero with a Thousand Songs

Why Is the Oldest Book in Europe a Work of Music Criticism? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Is There a Science of Musical Transformation in Human Life? (Part 1) (Part 2)

What Did Robert Johnson Encounter at the Crossroads? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Why Do Heroes Always Have Theme Songs? (Part 1) (Part 2) (Part 3)

What Is Really Inside the Briefcase in Pulp Fiction? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Where Do Music Genres Come From?

Can Music Still Do All This Today?

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

How We Lost the Ability to Listen

Part 3 (of 3) of “Why Do Heroes Always Have Theme Songs?”

By Ted Gioia

I sometimes wonder how different our culture would be if recording devices had been invented before the printing press.

Singing bards might still possess wider renown and more authority than writers. The aural/oral tradition would be enshrined in great institutions—universities, libraries, archives. And songs would be treated as the cornerstone of the humanities and learning, not an afterthought.

In that kind of world, people would learn how to hear with discernment—perhaps the greatest skill of all (highly underrated compared to talking). Scholars studying epic histories, lyric expressions, folk ballads, and other communal narratives, would treat them as essentially musical forms of expression, not literary works flattened into black-and-white words on a page.

Heroes would never have lost their empowering music. Even laws would be sung (as they once actually were).

But that’s all idle dreaming. We live in a culture dominated by text and images—not listening.

Almost as soon as the printing press was invented, publishing became a lucrative business—and texts gained widespread acceptance as the only legitimate repositories of wisdom. In effect, books assumed the same role that shamans, bards, and griots had once held with such fierce pride.

When you sought enlightenment, you no longer went on a vision quest and brought back songs of magic and wisdom. Instead you found a book store or library, where every branch of learning had its assigned place on the shelf.

As a result, the wisdom songs of pre-literate communities mostly disappeared without a trace.

Why? That happened because, according to the dominant Western model, we value most what is easiest to encode. So text and numbers are always given precedence over sounds. Eventually we lost our ability hear with discernment.

It’s not easy to hold on to a sound.

Music notation systems emerged only gradually, and preserved merely the tiniest fragment of the total musical culture of traditional societies. And as printed books spread over the world, scribes and scholars took over almost every important role once held by singers—former sages who were now relegated to the diminished status of entertainers.

But even more important, for our purposes, was the new attitude towards heroes embraced by the dominant literary establishment. Among the educated, epic songs and folk ballads were replaced by the novel—a new method of storytelling, elaborate and nuanced, that achieved enormous popularity during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Novelists had no patience with the traditional heroes of earlier generations. In fact, the first great novel, Cervantes’s Don Quixote, asserted its supremacy by mocking the entire hero mythos, and showing just how absurd it really was. It was literally tilting at windmills.

The main protagonist of this picaresque novel, Don Quixote, is a man who goes mad from consuming too many stories about chivalric heroes, and decides to go on his own hero’s journey in search of adventure and romance. Every meme of the traditional quest is included at some point in this novel, but only to be ridiculed and found wanting.

Yet even Cervantes, for all his wit and insight, is unable to destroy the heroic grandeur of this venerable tradition. And the reader can’t help admiring the deranged protagonist of this sprawling book, who somehow still discovers magic and enchantment in a world that others find merely prosaic.

By the way, that’s a word that sums up the entire ethos of the literary world we inherited from Cervantes. Prosaic both means writing that has abandoned the musicality of song and rhythmic poetry, but also has come to signify anything that is dull, everyday, ordinary. It’s what the world is like when we stop hearing, and instead merely encode and decode.

If we live, as some claim, in a world that is disenchanted, robbed of its mystery and higher metaphysical powers, this decisive moment—when the Renaissance gave way to the period now known as the Enlightenment—was when it happened. The Western world lost its inherent musicality, and the end result might have been more rational, scientific, capitalistic (or whatever word you want to apply here). But it was no longer a magical, musical, mystery tour.

Even Cervantes feared the deadening impact of turning musical heroes into mere words on the page—and that’s why he borrowed from musical precedents at every turn in his famous book. Not only did he rely heavily on the folk ballads of his day, but even the opening words of Don Quixote (En un lugar de La Mancha…) are taken from a pre-existing song.

And this borrowing continues throughout the book, with so many phrases, incidents, and characters drawn from the sung ballad tradition that it soon becomes obvious that the first great novel in the Western world was built, in large part, from musical precedents. That’s because Cervantes grew up in a world where anyone seeking wisdom still needed to know all the right songs.

We’ve lost that world today. Part of my purpose here is to explore ways of recapturing at least a little of what we’ve lost.

A full account of how literary movements undermined musical conceptions of heroes and their journeys is beyond the scope of this book. But it’s hardly going too far to see the rise of the novel as an attack on the whole bardic concept of heroism, with its old-fashioned notions of wisdom, courage, fidelity, and valor.

You can detect this attitudinal shift in every one of the great writers who established the novel. The new protagonists in these books weren’t brave knights and courtly ladies—unless those figures were getting deconstructed and mocked, as in Cervantes. Instead we read about Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders (eponymous novel from 1722), celebrated for her crimes and harlotry; or Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones (eponymous novel from 1749), the bastard son who overcomes scandal and trickery to make his way in the world; or Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa (1748), whose protagonist deals with sexual assault, anorexia, and a litany of other obstacles.

Traditional songs, for all their boasts of magic and wisdom, could never match this degree of intense realism, drawn from everyday life.

How far could novelists push this demystification of the hero? It might seem that Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) reached the limit: What could offer less scope for traditional nobility and knightly valor than the story of a man shipwrecked on a deserted island. But Laurence Sterne pushed even further with Tristram Shandy (1759), in which not only the whole notion of heroism, but even the basic rules of narrative are treated as little more than nonsensical conventions, suitable for a laugh and endless put-ons—but nothing anybody could take seriously. Our narrator promises to tell the story of his life on page one, but when we get to volume four he is still recounting the day he was born.

If you come to a book like this seeking guidance or wisdom, the joke is on you.

But at the very same moment that musical heroes and their quests got evicted from the novel, they came to the forefront in another art form—namely the opera. And if you have any doubts about the close connection between opera and the hero’s journey, you merely need to look at the subjects of the first operas.

No hero was more celebrated by early opera composers than Orpheus, the very same proto-shamanic figure who stands at the origin of the musical quest in Western culture. The oldest opera whose music still survives is Jacopo Peri’s Euridice (1600), composed for the marriage of King Henry IV of France and Maria de Medici, which tells the story of Orpheus’s journey to the Underworld to bring back his dead wife. In its debut performance, the composer himself performed the role of Orpheus.

And this story was so compelling, that Peri’s rival Giulio Caccini composed his own opera on the subject, also called Euridice, two years later. You might even say that opera originated as music to raise the dead—in eerie echo of music’s ritualistic role thousands of years before these composers were born.

Then Claudio Monteverdi surpassed both of these predecessors with his L'Orfeo (1607), which is the oldest opera still widely performed as part of the standard repertoire. As these examples make clear, opera—just like so many epics, folk ballads, myths and other narratives before it—originated as a musical celebration of a hero’s journey into a dangerous realm. And they focused on the exact same hero (Orpheus) who—as we learned in chapter one—is the central figure in the musical wisdom tradition of antiquity.

Consider the curious fact that these operas were staged at the very same moment that Cervantes was writing the first great novel Don Quixote—part one of that masterwork was published in 1605 and part two in 1615—with its profound critique of the traditional quest hero. In fact, the rise to prominence of the novel in European literary circles coincides almost exactly with the timeline of opera emerging as the dominant form of mass entertainment in every major European city.

And if you left these large cities, the folk ballad played the same role for village and rural communities, celebrating traditional heroes in songs even as these old-fashioned narratives were derided by the leading novelists of the day. In other words, the musical hero’s journey never disappeared from Western culture—if you knew where to look for it.

Literary culture may have forgotten it. But it never really disappeared. Heroes still retained their songs.

If we had time, we could trace this cultural tension as it evolved decade by decade, century by century. Suffice it to say, only a small number of people ever really believed that music-driven heroes, with their quests and adventures, were outmoded. Everyone else—that group we would now call the mass audience—knows differently.

And if that was true with musical dramas and folk ballads, it would prove even more true with the advent of new mass entertainment platforms. In movies and TV shows, video games and web series, heroes still come equipped with powerful songs.

And by holding on to the hero’s music, these mass media platforms somehow needed to pledge allegiance to all the old heroic values too—bravery, honor, duty, vigilance, endurance, fidelity, etc. Heroic songs still try to convey wisdom and cultural values, even in these degraded contemporary contexts.

Mythologist Jospeh Campbell once talked about the “Hero with a Thousand Faces,” but at least nine hundred of them now show up for work at the Walt Disney Company every morning.

It’s one of the great paradoxes of modern pop culture: the newest of new media build brand franchises on the oldest ethical system in human history, namely the simple virtues of a heroic worldview that dates back thousands of years to Homer and Gilgamesh and other sung epics.

You could hardly find a more eloquent testimony to the power of the hero’s journey (or virtue ethics). Even as these larger-than-life protagonists got squeezed out of the serious novel, whose authors typically preferred more realistic and nuanced character traits, they found a receptive audience in almost every other kind of narrative.

At every stage of this history, we encounter music.

It’s hard to avoid concluding that songs are somehow linked to this timeless image of heroism and its ethical imperatives. And it’s true: If you took away the theme songs and exciting soundtrack music to the films and video games, something essential is lost. We’ve come a long way from the ancient epics, but Odysseus and Han Solo have at least one thing in common. They both depend on musicians, although in one case it’s a singer of tales and in the other a Hollywood composer.

I’ve seen intricate taxonomies of music genres, which divide and subdivide songs into every possible category from glitch hop to folktronica. I’m told that the Spotify streaming platform has identified 1,300 different genres of music. Yet these lists never include the genre hero music—the oldest and most enduring song of them all and the root of all narratives. Like other genres, it morphs and evolves, but it never disappears.

Romanticist music of the nineteenth century was self-consciously heroic, and created an aural palette that still impacts film and video game soundtracks today. Even the bosses at the NFL have learned that a running back’s touchdown or quarterback downfield pass are more heroic if they borrow from Beethoven and Wagner’s playbook.

Yet there’s a larger problem here, and it’s very much the focal point of this book. Heroes have retained their music, but at a tremendous cost. Our heroes have been bought out, co-opted, turned into profit-generators by the entertainment industry—businesses which neither understand nor care about wisdom or authentic quests or powerful songs, even as they manipulate these ingredients in crass, opportunistic ways.

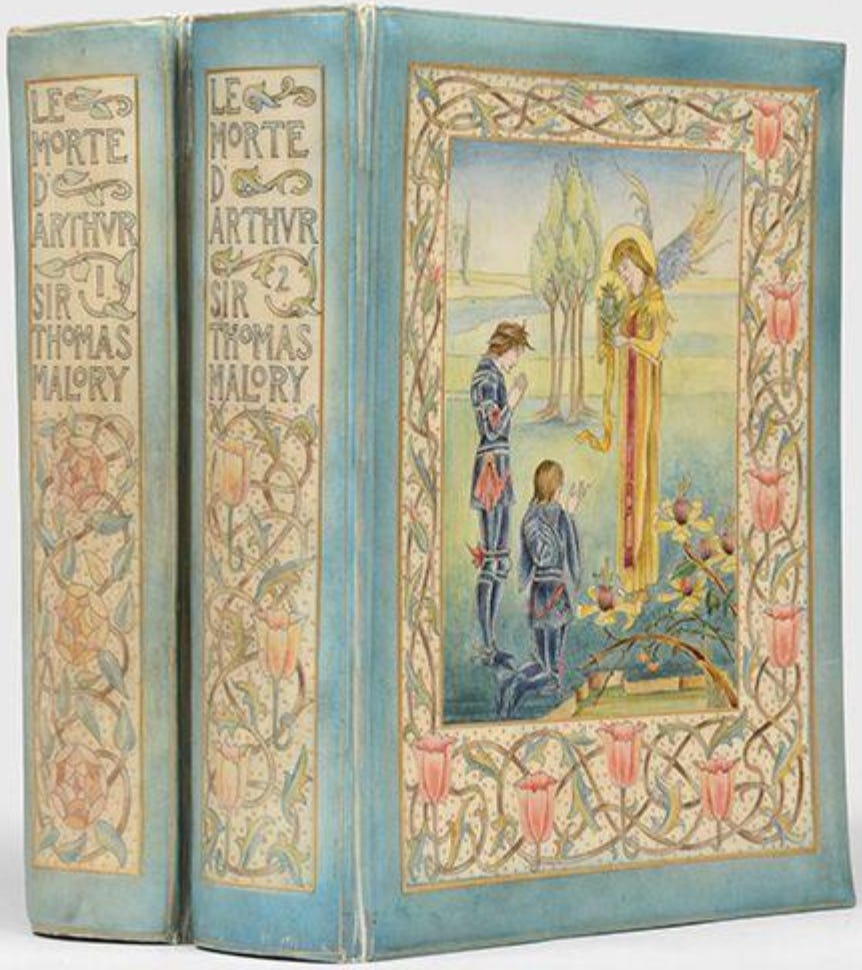

This is evident at the very origin of these storytelling businesses, notably in the money-making decision by publisher William Caxton, the first commercial bookseller in England, to turn the traditional Arthurian legends into the popular book Le Morte d'Arthur (1485). A queasy tension permeates this influential prototype for the modern adventure tale, as two different philosophies of heroism battle for control of the printed book.

In the first two-thirds of the story, author Sir Thomas Malory sticks close to the familiar formulas of the storytelling business—providing the reader with a seemingly endless series of jousts, sword fights and romances. But then in the final chapters, something amazing happens.

In the last third of Le Morte d'Arthur, the story takes a bizarre turn. Major characters start having dreams and visions, most of them centering on a peculiar quest for an object called the Holy Grail.

But what is it? The Grail is presented here with a strange mixture of reverence and ambiguity, almost as if its properties were too great to allow close description.

And from that point onward, the heroes in Le Morte d'Arthur start rebelling against their role in a brand franchise.

They no longer revel in the glory of battle, but seek pathways to wisdom and a higher plane of existence. It’s almost as if our enigmatic author—and who, really, is Sir Thomas Malory?—is conflicted between two ways of writing this book. One way is to please his publisher with a story that anticipates later Hollywood adventure movies, while the other pays homage to an ancient tradition of heroic vision quests incompatible with crass money-making schemes.

More than 500 years have transpired since Malory felt the conflicting pull of these two opposed concepts of heroism. But little has changed—except that the profits at stake are massively larger than anything William Caxton could have imagined.

Heroes now earn huge financial rewards for their corporate owners. Disney has generated more than $20 billion in revenues from Marvel comic book heroes, since buying them out in 2009—for a purchase price of only $4 billion, a sweet deal by any measure. And three years later, Disney took control of the Star Wars heroes for another $4 billion, and proceeded to launch an unending series of films, TV shows, theme park attractions, and other spin-offs.

These are now the twin money-making engines for a global corporate empire of unprecedented scope. And it’s all built on heroes, from the humble animated mouse (a hero in his own way) that set the whole Disney business in motion a century ago, and now includes everything from Ant-Man to Zootopia.

Mythologist Jospeh Campbell once talked about the “Hero with a Thousand Faces,” but it now at least nine hundred of them show up for work at the Walt Disney Company every morning. But there are still a few stragglers who operate out of different corporate headquarters, such as Harry Potter (estimated value = $25 billion) and James Bond (estimated market value = $20 billion), and—most unlikely of them all—an overalls-clad plumber named Mario (estimated market value = $30 billion), who may not have much charisma, but still struts along to his familiar theme songs, traveling on adventures and bringing home the bacon to Nintendo Co., Ltd.

These heroes and their exploits offer a cartoonish caricature of the true quest, which is hidden from view in the modern day. And the more pop culture obsesses over these formula-driven characters, the less capable we are of grasping the true possibilities for a transformative journey and magical aural experiences in our own lives.

We no longer hear with discernment. We no longer sing our own powerful songs. We merely stare into the screens.

Of course, only a fool would turn to the entertainment industry for wisdom and transcendence. If you have any doubts, just consider how those Hollywood moguls lead their own lives. Or, for the ultimate warning, imagine what your life journey would look like if you tried to follow the example of a Marvel superhero or Call of Duty first-person-shooter video game protagonist.

That way madness lies.

But what price do we pay when these sad heroes are the only ones available for mass consumption? Or when the hero’s music, which back at the time of the Derveni papyrus offered a promise of transcendence to all who could listen, gets displaced by bombastic soundtrack music to accompany shoot-outs, chase scenes, and various forms of mayhem and mass destruction?

No, heroic music hasn’t disappeared. But, given these modern instances, it might be better if it had.

We now need to launch our own pursuit of a magical grail in the next chapter, but before proceeding let’s summarize what we have learned in this one.

Singers invented the concept of heroism, and taught it to discerning listeners over the course of thousands of years, but this musical linkage is forgotten nowadays. As a result, we’ve lost much of our ability to hear with discernment, and use music in transformative ways.

It’s hard to identify an exact turning-point in this process, but 1485 is a plausible birth date for the hero as a brand franchise. That year saw the publication of Le Morte d'Arthur by William Caxton—the first printer and bookseller in Britain—and represents a milestone moment when the bardic tradition, which had long shaped how heroes were sung and celebrated, got displaced by the profit motive

The subsequent rise of the novel as the main commercial platform for literary narratives demanded a new kind of hero—deconstructed, demythologized, and deprived of all musical support. Don Quixote, the first great novel, explicitly mocks and satirizes the older style of heroism, and similar approaches can be found in Fielding, Defoe, Richardson and other pioneers of this new form of storytelling.

Yet even as heroes got deprived of their music in novels, they retained their songs in other narrative forms—notably the folk ballad and opera. In these settings, the tradition of heroic music continued uninterrupted, and often made clear its ancient roots. For example, the most popular hero in early opera was Orpheus, who also inspired the Derveni papyrus, studied back in chapter one, and is the defining shamanic figure in Western culture.

Heroic music also persists in other narrative forms, even the most high tech and up-to-date (video games, movie soundtracks, etc.). Every significant hero-driven brand franchise in the contemporary world has its incantatory theme songs. These are so important in movies and video games that the same themes are used over and over again—James Bond, for example, has retained many of his same melodic motifs for more than sixty years.

Musicians themselves have emerged as powerful cultural heroes and antiheroes. In fact, musicians have played the key role in creating the concept of the antihero—perhaps the most significant innovation in narrative during the last century.

The profit-driven concepts of heroism promoted by Hollywood and high-tech media are degraded versions of the actual quest hero. Heroes once sought wisdom and transcendence, and their music was a pathway to another world. Brand franchise heroes are instead obsessed with fights, chase scenes, and special effects.

This situation has created an unresolved cultural tension. The profit-driven heroes can bring in billions at the box office, but still not fill the huge gap in the modern psyche created by the erasure of the vision quest and the marginalization of the transcendent music that once empowered it.

Click here for Chapter 9: “What Is Really Inside the Briefcase in Pulp Fiction?”

As luck would have it, I'm currently reading Tales of Genji, another oft-cited contender for the title of "first novel," in this case, from the 11th Century. Murasaki Shikubu's work provides a fascinating counterpoint since, much of the time, one can't help but see the prose as an excuse to get to the "music." That the term "Waka" (和歌) translates not as "Japanese poem," but "Japanese song" is often neglected by Western literary commentators, who've worked very hard to obscure the importance of singing to this tradition. Why do they think Genji's playing his kin-harp all time?

Japanese is timed by mora, not syllables, as in some European language, or stress as in English. It's not, 5-7-5 syllables for a haiku - it's 5 units of language, 3 units of pause, 7 units of language, 1 unit of pause, then 5 more units of language, 3 and more units of pause. That's 8 unit's a line - or common time: You can read more here:

https://haikupresence.org/essays/haiku-rhythm-and-the-arches-of-makudo/

It seems to me the more "balanced" approach of novels like Tales of Genji is a model worth considering, along with the very different trajectory of Japanese culture before the Meiji Restoration. Reading this chapter also brought to mind how things have followed a different pattern in Bollywood, and it would be interesting to consider how it relates to what's discussed here. There's a lot to think about.

"anyone seeking wisdom still needed to know all the right songs."

And still does, she says, as she listens to Leonard Cohen.

Your book makes me very glad that , with a few notable exceptions, I stopped going to the movies and watching TV twenty years ago...