Have Non-Musicians Taken Over Music Scholarship (and Should We Care)?

A new book reminds me of the STEM-ification of musicology and how desperately we need more interdisciplinary dialogue about music

One of the most important books on music history this year was written by a science writer trained as a mechanical engineer. Should I be surprised? Probably not—many of the most significant works on music in recent years have come from scholars without degrees in music.

No, I’m not talking about music fans—who often undertake important research (especially in my own specialty, jazz). Music journalism has never been dominated by professors, and frankly I’m grateful for that fact. In this instance, I’m referring to something very different: namely, trained scholars with doctorates or other impressive credentials outside of music, who find that their specialized research in their discipline has led to significant discoveries about songs.

In fact, if I listed the works that have exerted the greatest influence on my thinking about music over the last three decades, most of them would come from outside of music academia—showcasing the latest research in neuroscience, evolutionary biology, cognitive psychology, mythology and folklore, sociology and anthropology, cultural history, and other disciplines.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

For example, my understanding of how musical traditions migrate around the world has been transformed by the provocative research of Harvard professor Michael Witzel, a philologist whose massive study The Origins of the World's Mythologies analyzes, over the course of 700 pages, how certain core myths evolved and spread all over the globe—a process that took thousands of generations to play out. These same myths were often preserved in the form of songs, and Witzel’s powerful hypothesis thus has significant bearing on ethnomusicology and the ongoing (and heated) debate on musical universals—but, alas, his research seems all but unknown among musicologists.

Or consider the work of renegade classicist Peter Kingsley, whose bold theories about pre-Socratic philosophers and cultic practices make clear that Western thinking systems probably originated as songs. His work has exerted more impact on my recent research than almost any musicologist. (I even send him emails, which are half fan letters and half serious scholarly inquiries, but—alas!—can never get beyond his assistant, who regrets to inform me that Dr. Kingsley is busy, etc. etc. )

By the same token, my understanding of Mozart and Haydn has been tremendously enriched by scholar Antoine Lilti, who teaches modern history at the École Normale Supérieure, and has shown that our concept of celebrity emerged at the same time that the composer who launched the classical style became famous—thus providing an invaluable framework for grasping how our notions of concert music were transformed permanently during this era.

I’ve also drawn heavily on the research of psychologist John Sloboda, who may have done more work than anyone alive on how music is embedded in human life. And I’ve learned much from the studies of poet and polymath Frederick Turner, as will become very clear in my next book, whose inquiries into poetic meter have helped me understand the role of rhythm and phrasing in various cultures. And while on the topic of the beat, how about the work of Tam Hunt and Jonathan W. Schooler, who tell us that rhythm may be the very building block of physical reality?

And, frankly, nobody in music scholarship has shaken up my concepts of performance as much as René Girard, J.L. Austin, and Mircea Eliade—although the first is usually described as a literary critic, the second a philosopher, and the third a historian of religion.

This splintering of knowledge is, perhaps, inevitable. But the absence of a significant, ongoing dialogue between music scholars and these other disciplines is regrettable. Perhaps neuroscientists, for example, are overreaching and reductionist in their attempts to ‘explain’ music—but no matter what your views on that topic, the efficacy and value of their research will be improved if musicologists engage with them in constructive dialogue. And the same is probably true of many STEM fields that are now ‘encroaching’ on music studies—just wait and see what damage will be wrought by algorithms and artificial intelligence. Nothing in the music world today will have more impact than these expert systems, created by well-meaning outsiders who will completely change our musical culture, often without actually understanding it.

This trend won’t end any time soon—if only because STEM researchers have access to much more grant money than any musicologist can even dream of. If scientists want to take over music scholarship, no one will stop them. They will even get a blank check and a comfy corner office to help them do their work.

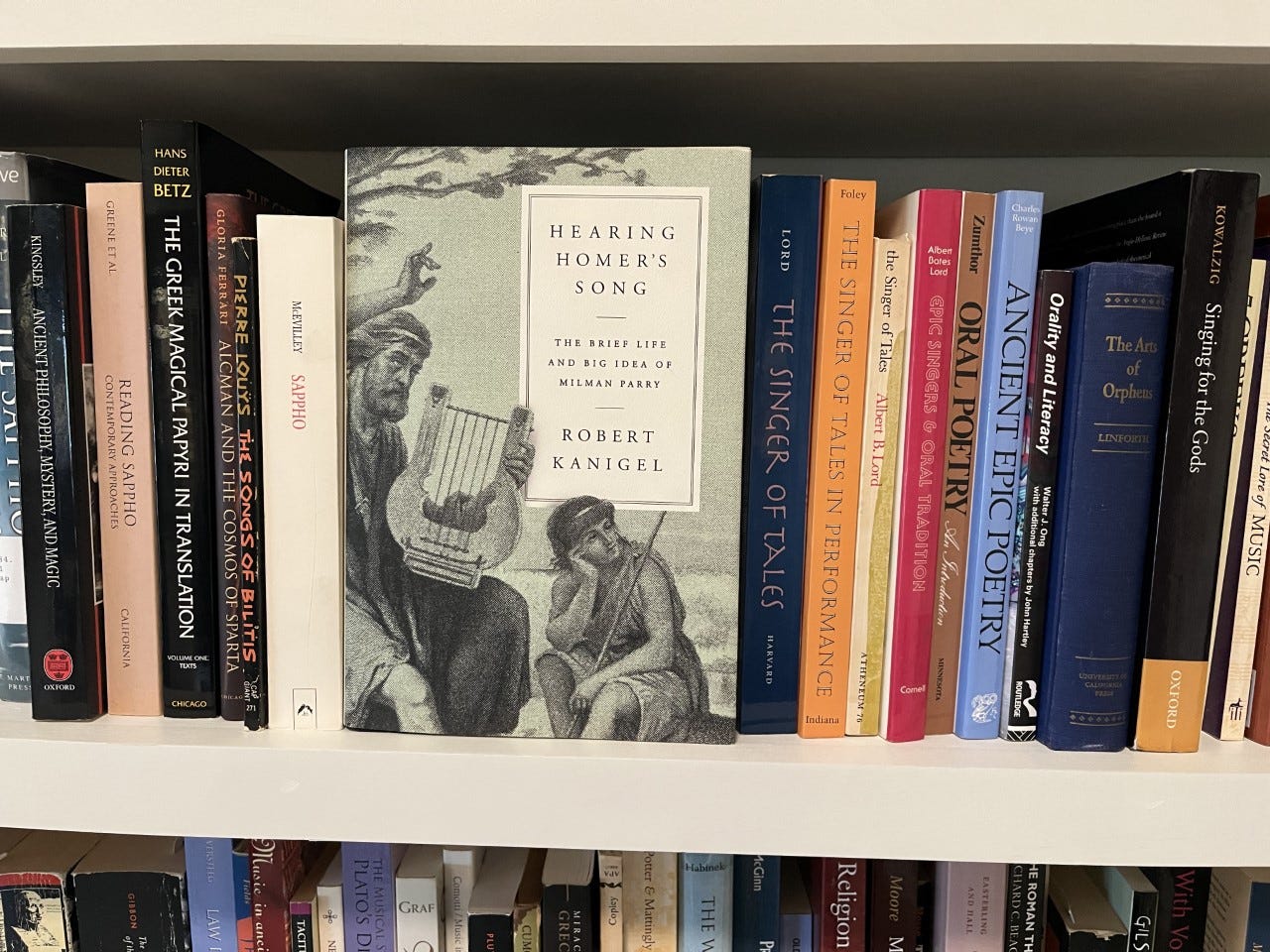

But I’m a music historian, so it’s eye-opening to see so many books specifically addressing music history written by outsiders. The most recent example is Hearing Homer’s Song, an in-depth study of Harvard scholar Milman Parry (1902-1935), whose intrepid fieldwork in Eastern Europe demonstrated how highbrow Western culture originated in the songs of pre-literate performers. This is simply the latest in a long series of books on the origins and functions of music coming from scholars outside the field, but one of the best.

You could make a case that Hearing Homer’s Song written by Robert Kanigel—the aforementioned mechanical engineer and science writer—is as important as any music book published in 2021, except that no one even thinks to call it a music book. Take a look, for example, at the publisher’s website, where it is tagged as history, biography, literary criticism, even entertainment—yet the word song in the title is significant.

We now know that the ancient epic tradition simply must be studied as a musical practice. But if you look at the most frequently cited scholarly works on epics, almost every one operates from the perspective of literary criticism or classical studies. The same is true of the troubadour tradition, which was undoubtedly the outflowing of a musical culture, but is almost always studied as a body of poetic texts on the printed page. Or consider the ancient lyric tradition of Sappho, who was essentially what we would call nowadays a singer-songwriter, but poets have adopted her as their own. And for a good reason—who wouldn’t want to have Sappho as part of their lineage and tradition? But I am puzzled that our music institutions don’t fight harder to hold on to her—and other great musicians of antiquity such as Hesiod or Homer or Parmenides or Empedocles or Solon or Pythagoras. Music was at the heart of what they did, yet none of them are considered musicians by posterity.

“STEM researchers have access to much more grant money than any musicologist can even dream of. If scientists want to take over music scholarship, no one will stop them.”

Just consider the extraordinary nature of Parry’s discovery that singers in coffee shops held the key to grasping the birth of ancient literary culture. Or his almost conclusive proof that the masters of this tradition were illiterate herders. Or that their ability to recall and deliver complex story songs disappeared if you took their string instrument from their hands, and asked them to recite lyrics without musical accompaniment. Or that the improvisational techniques and patterns that led to the birth of the Western epic are virtually identical to those used by jazz musicians in the 20th century.

These are remarkable facts. And without Milman Parry we wouldn’t know them. But even more significant are the implications—many of them still still neglected after almost a century—that his research should have opened up in other spheres of music history and practice.

It might seem like an exaggeration to claim that our culture is essentially musical in its formation, even fields far outside the arts and humanities—but there’s an abundance of evidence to support this view. In my next book I will show, and substantiate with a large body of multidisciplinary research, how modern cultural institutions that seem to having nothing to do with music, actually were created by singers—but in ways that are now hidden from view. In fairness to Milman Parry, he laid the groundwork for this approach almost a century ago.

The current revival of interest in Parry makes clear how much these outside researchers might benefit from a dialogue with those who deal with singers and songs on a daily basis. For example, it’s worth probing into the strange—perhaps even bizarre—fact that Parry proved that the epic tradition was created by singers, but later scholars stubbornly avoided calling this music, instead preferring the odd term oral literature. And after making this deft substitution, they can proceed to analyze these works with little or no consideration of them as songs As a result, scholar Walter Ong can release an extremely influential book Orality and Literacy, which only uses the word “music” once, in passing, in a work that asserts the significance of oral culture in traditional societies.

But the main repositories of this revered oral tradition were not talking heads. They didn’t merely deal in what Hamlet mockingly calls “words, words, words.” They were actually singers, bards, griots, shamans, etc.—in effect, the presiding experts of musical practice. You can’t understand the formation of cultures and societies, without comprehending this overwhelming fact. In other words, civilizations are built on a musical foundation—a claim that seems extreme, but is scrupulously valid. Even more significantly, we don’t grasp the potentiality of music in our own times if we fail to encompass this same power to construct and define communal beliefs, meanings, and institutions.

Milman Parry learned, to his surprise, that the greatest performer of epic works he found during his fieldwork, peasant farmer Avdo Međedović, was only capable of remembering these stories if he had his gusle—a one-stringed instrument—in his hand. As soon as he was deprived of this musical support, his skills dissipated. It might be worth noting that this Balkan instrument is similar to the diddley-bow, which played a similarly foundational role in early African-American musical culture. But that connection is not mentioned in the current book—and who can be surprised, when such a large divide exists between music scholars and the people writing books on “oral literature”?

By the same token, a book devoted to Milman Parry’s discovery of the virtuoso folk singers in Eastern Europe ought to mention that song collector John Lomax met an African-American singer named James “Iron Head” Baker at almost that same moment in Huntsville Penitentiary in Texas—and that he described this inmate as a “Black Homer” because of his extraordinary ability to remember and perform intricate story songs. But Baker isn’t on the radar screen of science writers, and is thus omitted from the account. The same is true of Vasily Shchegolenok, the amazing illiterate epic singer who so dazzled Leo Tolstoy that the latter imitated aspects of these sung tales in his world-famous fiction. Also neglected by experts in “oral literature” is the herder Beatrice Bernardi, who demonstrated an awe-inspiring ability to deliver intricate story songs for art critic John Ruskin.

The memory and performance skills of these unschooled singers almost defies belief. Međedović performed, for his Harvard visitors, an epic entitled The Wedding of Smailagić Meho, which took seven days to complete. When it was published in book form, it filled up 12,311 lines—which is almost the same length as Homer’s Odyssey. Certainly this is a great achievement of “oral literature”—but if you actually watched this artist in performance, you saw immediately that he was a musician, not a literary figure.

Here’s a rare video clip. I can’t prove that Međedović was in a kind of trance, almost shamanic in intensity, when he made this music, but watch and decide for yourself. And what a different perspective you have on highbrow culture when you grasp that this was how it originated.

But even as I gripe over how music gets removed from the history of “oral literature,” I still learned a great deal from Kanigel’s book. It shows how Milman Parry was almost forgotten even within his own field of classics. For decades, his reputation was overshadowed by his own student, Albert Lord, who completed and published his mentor’s research after Parry’s untimely death at age 33.

When I first learned about Parry and Lord’s work—back in my college days, when a professor of literature suggested it might be useful as part of my research into jazz—I was only told about Albert Lord, not Milman Parry. The breakthrough book on the subject, The Singer of Tales, was attributed to Lord alone—at least on the title page. Yet the actual text makes clear how much Lord needed Parry.

Lord had little expertise when he went to Yugoslavia in the 1930s as Parry’s assistant, almost what we would call a “gopher” today. He took care of the physical recordings, and that was a full-time job in itself. Parry wanted to preserve the songs of these singers, and eventually collected a half-ton of recordings, preserved on 12-inch aluminum disks. The entire collection, now held in Harvard’s Widener Library, amounts to some 3,500 disks.

These would revolutionize our understanding of the epic tradition. But The Singer of Tales also shaped my sense of how jazz must have been created by its earliest practitioners. When I first read Albert Lord’s book, I was struck by how closely the formulas and patterns of his Balkan epic singers resembled jazz improvisations. I was around 20 years old at the time, and was making an in-depth study of the recently published Charlie Parker Omnibook, the first widely-available collection of transcribed bebop solos. I was making particular note of the trademark phrases that Parker repeated in solo after solo—and was trying to decide whether this reliance on stock devices was a flaw, or some kind of signature statement by Parker, or filled some other role in the music. Lord helped me comprehend that these formulas are essential ingredients of all improvised or semi-improvised musical traditions.

In essence, Charlie Parker’s bebop licks were his equivalent of Homer describing the dawn as “rosy-fingered” or Achilles as “swift-footed.” The phrases have both artistic value in enhancing the expressiveness of the work, but they also fill up the right number of beats in the form, allowing them to be used as pieces in an elaborate musical jigsaw puzzle.

So my own personal journey in jazz was enhanced by Milman Parry’s inquiry into the roots of the Western epic. It’s precisely these kinds of connections we ought to make between songs and other disciplines in the current moment—that’s an approach that will help us understand music more profoundly, grasping the myriad ways it is integrated into the overarching concerns that motivate individuals, communities, and entire societies.

Musicologists have a vital role to play in laying the groundwork for this multidisciplinary research, thus keeping the STEM folks, with their deep pockets, on the right track. But those of us devoted to music as our main focus of inquiry also benefit in turn by engaging in these dialogues. After all, music is embedded in every significant aspect of human life, and if songs are our specialty, we now have a lovely excuse to pursue our inquiries almost anywhere and everywhere. That might look like a heavy responsibility, but it’s actually an invitation to expand our knowledge and impact, as well as to enhance the joy and delight we take in our craft.

Trying to picture Mededjovic’s 7 day concert - and that’s without any bass solos? Amazing stuff here. Thanks for keeping track and making cliff notes for us in the back of the hall. As always, your efforts are enjoyed and appreciated.

Again, thank you.