Welcome back to The Honest Broker interview series —also available on our new YouTube channel. You can also find it on Apple Podcasts and other podcasting platforms.

Today, I’m pleased to share my conversation with C. Thi Nguyen.

Please support The Honest Broker by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

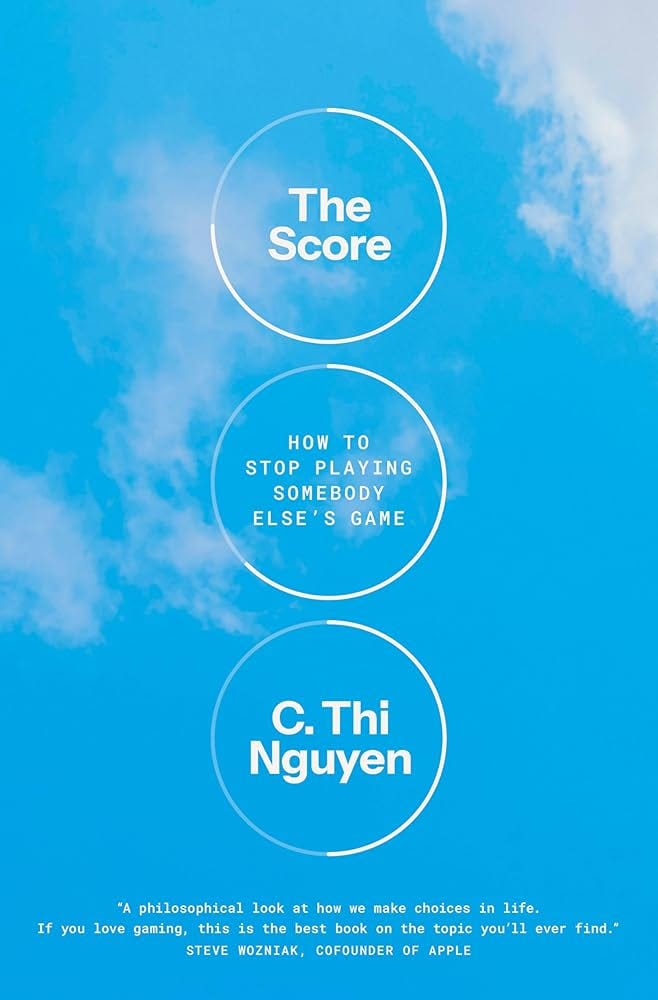

Nguyen is a former food writer who became a philosopher. He’s now an Associate Professor of Philosophy at the University of Utah, where he also teaches in the Division of Games. His first book, Games: Agency as Art, won the 2021 Book Prize from the American Philosophical Association.

In January, Nguyen released The Score: How to Stop Playing Somebody Else’s Game. It’s an exploration of the philosophy of games and a critical examination of the detrimental effects of gamification and institutional metrics. (I wrote a review of The Score on my own Substack.) Jennifer Szalai described The Score in a review at The New York Times: “This may be the only book in existence that discusses the game of Twister, the ethics of Aristotle and the mechanics of bureaucracies.”

Below are highlights from my interview. For the rest of our conversation, check out the video at the top of the page.

Highlights from the C. Thi Nguyen Interview

Jared: Thi, thank you for joining me.

Thi: I’m happy to be here.

Jared: I want to start off with a big broad question: why are games fun?

Thi: There are so many answers to that. I’ve given much more complicated answers, but maybe the dumbest answer is one of the deepest. Games are actually designed to be fun. Not all games, but a lot of the games we find fun are not accidents. It’s an ultra-careful fine-tuning process.

Designing for fun is so delicate. If you just tweak a few little bits in the incentive structure or tweak a few little rules, the fun will fall out of things. People think fun is mysterious — it’s not for game designers. There are micro-issues of exactly how you pace the timing and exactly how you pace the rules that seem to emerge. A lot of people are most impressed by the game designs that are elaborate and complicated, but what a lot of game designers are most impressed by is a five-rule party game that’s fun, because that’s the hardest thing to build.

I think it’s important to acknowledge that these things are designed objects that have been subject to brutal design cycles.

Jared: If I’m playing games, I have two very different preferences. One of them is that I really like cozy games, like Stardew Valley. But then my other love is roguelikes, which are so frustrating. I played Slay the Spire last night, and I never made it to the last level. It was an intentionally frustrating experience, and I went to bed happy. I think that’s weird. The challenge is why you want to keep playing, and it makes it more satisfying.

Thi: Roguelikes are probably the center of my video game universe. But when you asked about fun, I immediately thought about laughter, the social part of fun. In game design circles, ‘fun’ is used a little more technically, where they are talking about ‘fun games.’ I have the same experience as you that most of what I love is intensely, gruelingly difficult and mostly involves failure and pushing your way intensely to get tiny moments of success.

I have a theory about why that is deeply enjoyable for us. In games, unlike ordinary life, you can seek exactly the balance of difficulty, frustration, skill, and success that suits you. That’s unlike the world, which says ‘Now you must work on this thing at this difficulty.’ The choice structure is that you get to choose whether you’re playing Stardew Valley or Slay the Spire, and that ability to adapt the challenge environment to you makes it much more possible to find the deliciousness wherever it may lie for you.

Jared: This is probably related to our mutual love of rock climbing.

Thi: Rock climbing taught me a lot. Climbing is what taught me to pay attention to my body and the way my body moves, and part of it was exactly the difficulty scale. It gave me feedback.

Godfrey Devereaux, who is one of my favorite yoga writers, has this amazing passage where he says that one of the reasons we do yoga is that a lot of us want meditation, but we fail at seated meditation. In seated meditation, when your mind wanders, you don’t notice because your mind has wandered. But when you’re in a hard yoga pose, if your mind wanders, then you wobble. That feedback tells you to go back.

I think climbing is a particularly neat example of this because in a lot of games, the choice of difficulty is kind of hidden in the background. But rock climbing really surfaces the subtle degree of choice.

Jared: I’ve only sustained one major injury from climbing. I cracked my fibular head on a warm-up climb. It was my second climb of the day. And what I thought was, ‘I can skip that hold because this is an easy climb.’ I was craving a certain kind of experience, and I rushed to get that experience. I rushed to the difficulty I was getting ready for. There’s also something potentially misleading about difficulty scales.

Thi: You’re opening up two completely different universes to talk about right now. One is about the pleasure of games, and the other is about data compression of seemingly objective scales.

Jared: Let’s stick with the pleasure of games. I’m trying not to lead with dystopia.

Thi: You’re making me realize something I hadn’t quite thought about. I had an original model with games where games set an exact mental state and attitude that you entered into as you entered the game. But as I was writing The Score, I ended up thinking a lot more about variable games like rock climbing and fly-fishing. We plunge ourselves into a goal, but we often step back and are able to modulate what that goal is to chase a particular kind of experience. You’re making me realize that there’s careful modulation of the game experience even in the process of warming up.

Jared: You get to be in control of your experience in a really nice way, which is related to what you said earlier, which is that life often does not give us that sense of control. Games give us a sense of power over our circumstances.

Thi: When I started working on games, I did not realize that they were as interesting as I have now found them to be. When I started working on it, I was just going to write one little paper because I was annoyed. I’d read a couple books on the philosophy of video games, and they were all using cinema theory, and I was like, ‘This is dumb.’

I think the big unlock was reading Reiner Knizia saying that points give you the motivational system. I was sitting around with friends, and I said, ‘The most important thing about games isn’t that they’re fiction. They’re like art governments. They’re governments for fun.’ You play around with rules and incentives and shape people’s actions—not to rule them, but to create a beautiful experience.

Jared: Let’s talk about The Score. One way of explaining your book is that you have a theory of games, and you give that to us early on in the book, and then you have a theory of something like pernicious gamification in which metrics are imposed, and we start playing these games in the rest of our lives. The big question you open up at the end of the first chapter is: ‘Is this the game I want to be playing?’ Tell me a bit about what led you to go from thinking about games, which are a source of joy, to thinking about this.

Thi: I was writing my first book, which is a love ode to games. Toward the end of writing it, people were like, ‘Oh, you love games, so you must love gamification.’ I hate gamification! My gut sense was that if you actually understood what was good about games, then you’ll see forced and pervasive gamification as kind of horrible.

The term I’m using for this process is value capture. This is when your values are rich and subtle, and then you are presented with a simplification of your values in an institutional setting, and these are typically quantified. The simplification takes over your reasoning and seizes your attention. It starts to replace your values.

Jared: Here are some examples: language apps, fitness trackers, law school rankings. In my own world of YouTube, we have views, likes, comments, revenue, and more. These become markers of good videos rather than thinking about educational quality, entertainment value, or just making something you’re proud of.

One thing you note is that when our values are rich and subtle, they’re usually qualitative. They can even be a bit ambiguous. We’re both analytic philosophers, and we’re always told to take the ambiguous and make it precise. But part of your book might be that ambiguity is where the freedom is. Ambiguity gives you a sense of ownership and agency. That clarity might also be fake clarity.

Thi: Yes! When I first started doing this, I used the term ‘gamification.’ But I’ve come to think that what actually matters is the long progress of the last thousand years of an emphasis on institutional accountability at scale. The thing I’ve been chasing is an attempt to explain why a lot of our values might be better captured by ambiguous, fuzzy, rough language, or by poetic, metaphorical language.

There are two dimensions, and I think they’re not quite the same. One of them is that when things are ambiguous, we have more degrees of freedom. The other is that there might be a real value there, but that drawing a clear, definable line is going to mess the essential fuzziness of the real thing.

Theodore Porter has this book, Trust in Numbers, where he’s trying to explain why bureaucrats and administrators compulsively reach for quantitative justifications. He says that qualitative communication is rich, open-ended, and context-sensitive, but it travels badly between contexts. Quantitative information is design to travel between contexts and make aggregation possible. What Porter made me realize is that the thing that makes metrics socially powerful is precisely that they have had context stripped out of them. It’s a design feature and a design bug in one.

Jared: One thing about quantified systems that I find so striking is that once you enter into this realm of legibility and numbers, it becomes nearly impossible not to engage in rankings.

Thi: One of the big lessons for me from philosophy of technology is that one of the best ways to think about the impact of a technological system—and I think metrics are a technological system —is to think about what they make easy and what they make hard. Consider maps. Dennis Woods in The Power of Maps has all these great questions. Why don’t maps show sound quality? Why don’t they show where the pleasant nature is? It’s because the map-maker is often interested in things like property lines and commuting by car.

Not every game has a scoring system. You can have a competition without a scoring system. You can go to the skate park and skate with your friends. Even if you have a similar goal, like Be the coolest, you can judge that in different ways. When you transition to official contexts like ESPNX, which require an official verdict, then you get this movement towards more easily countable targets, like flips and the height of jumps. The same thing happened in yo-yoing. The rise of the competition scene happened during the YouTube era, so there are records. The space of what counted as good yo-yoing was once much wider. There were a lot of tricks that were just done for beauty, or grace, or flow. Now, the scene is locked in on speed and difficulty. It sucks a lot of the joy out of those activities.

Jared: We could talk for hours, but we need to end. Do you have a book recommendation for our audience?

Thi: I want to recommend a book that I think is incredibly important for right now. It’s a technical book. It’s by a law professor, Julia Cohen, called Between Truth and Power. It’s an attempt to understand precisely the changes in property law that make our current world of data-ownership possible. The current world of data that we’re in right now didn’t have to be. It is a particular construct of a particular way of envisioning data as ownable that was created by very specific laws that are entirely changeable.

Jared: C. Thi Nguyen, thank you for me.

Thi: Thank you so much, man.