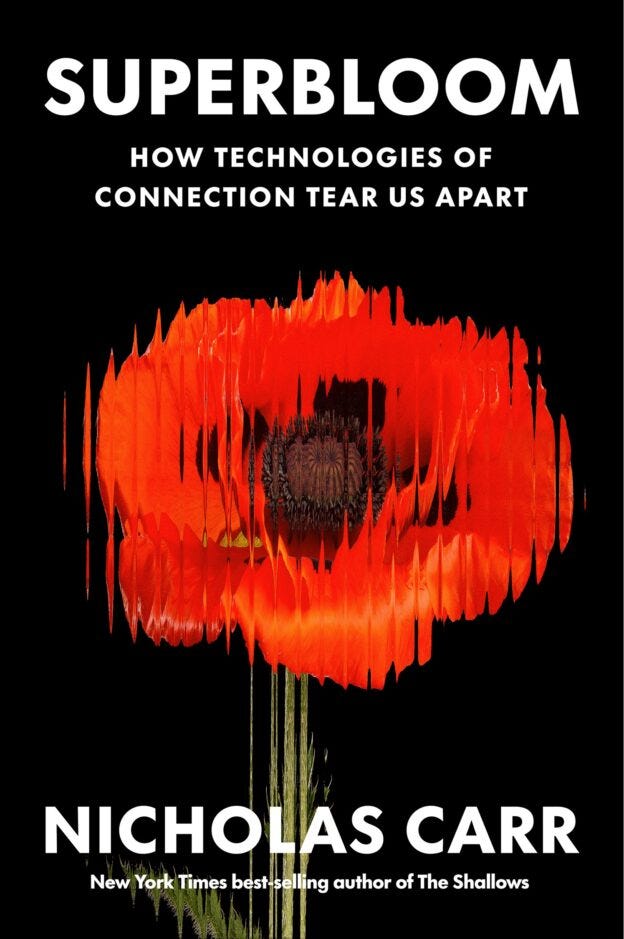

The Honest Broker interview series continues with a very special guest, Nicholas Carr. He is the author of The Shallows, a finalist for the 2011 Pulitzer Prize, and more recently of Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart.

You can watch here or on our YouTube channel. You can also find The Honest Broker Podcast on your favorite podcasting platforms.

Please support The Honest Broker by taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

Our conversation covers Nicholas’s turn to ‘tech skepticism,’ the fact that books like The Shallows sell a lot of copies but don’t seem to slow the adoption of these technologies, the history of technologies of connection like radio, and much more.

An edited transcript of highlights from our conversation can be found below.

Highlights from the Nicholas Carr Interview

For the full interview, check out the video at the top of the page.

Jared: As I looked over your career trajectory, it seems like you got to this tech skepticism fairly early. What was it that led you to this early skepticism of technology?

Nicholas: I actually started writing about technology in 1999, which was the peak of the first dot-com boom. What’s going on with AI today is kind of similar to what was going on in 1999. I enjoyed computers and computer networks. But then very shortly thereafter, the whole dot-com bubble burst. A lot of people who had bought into the enthusiasm and invested their retirement savings in it lost their retirement savings.

I think people are naturally enthusiastic and get naturally excited by new technologies because they’re cool and interesting. But this taught me that we need to be skeptical. And back in the early dot-com boom, people were focused only on the financial and the business side. Social bulletin boards and chat rooms and stuff were dismissed as childish. It turned out that the social effects ultimately have been the biggest change of all.

Jared: I revisited The Shallows recently and thought, “Wow, Carr saw something that was going to happen.” And your book was a bestseller. But the rate of technological adoption has, if anything, increased. How do you keep going?

Nicholas: I draw a distinction between people listening and people changing their behavior. Compared to when I started raising some of these concerns in 2005 or 2010, when The Shallows came out, people were were still in the grip of not only enthusiasm about the internet, but a kind of worship of Big Tech companies and their leaders. We saw them as kind of saviors that were bringing this unlimited amount of information to us. And if you look at attitudes since then, they’ve changed dramatically. I’ve never considered myself fundamentally an advocate or a crusader. I’ve seen myself as a critic, and it’s not my job to change how people live. That’s up to them.

Jared: How has it changed the way that you interact with technology? Because as writers or people trying to get a message out, the internet is the option. I make YouTube videos, and some of them are very critical of what online entertainment can do to you. And of course, a common comment I’ll receive is, ‘Well, why are you on YouTube?’ And my answer is that’s where everyone is. You have to go where people are to tell them how bad things are.

Nicholas: I started writing a blog back in 2005 and wrote it for almost twenty years and then switched to Substack. I’ve used the internet as a platform for personal expression for a long time, and I value it as that. On the other hand, I’m very sad that it’s eroding things like print media, because I think that’s actually a better medium to get things across. But as you say, you go to where the audience is as a writer.

There’s another angle, which is that I’m writing mainly about technology, about things that I think are often having harmful effects, but I have to keep using them, because if I stop using them I’ll have nothing to write about. I have to keep researching, and researching means using the technology. So the sad fact is that even though I’m probably at this point hyper-aware of some of the negative consequences, I, too, have not really changed my behavior. I’d like to present myself as this paragon of somebody who’s figured out how to use technology productively and well, but unfortunately, I can’t do that.

Jared: If you could spend decades thinking through these issues and then say ‘I’m still figuring it out,’ that might just reflect the complexity of the problem.

Nicholas: It reflects the complexities of the technology, which is constantly changing, and also the complexities of human psychology.

Jared: Tell me a little bit about some of the early optimism about things like radio.

Nicholas: Commercial radio came around in the 1920s, but almost a century before that, we saw the invention of the telegraph, which was the first kind of electric technology. It was the first time that speech and information, human expression could move faster than human beings could carry it. The telegraph comes along and suddenly long distance communication is instantaneous. This creates huge enthusiasm — not just enthusiasm, but a kind of wonder. For the first time, it seemed like something essential to an individual human being could be separated from their physical body and have its own life.

In the book, I talk about ministers and preachers talking about this as a gift from God. It becomes this sense that because we can communicate instantaneously with basically anyone around the world, then that’s going to solve all society’s problems, because all society’s problems come from a fact that people can’t talk to each other easily. Nikola Tesla said in an interview ‘I’m going to be remembered as the guy who got rid of war.’ There’s no way you would fight somebody when you can talk to them instead. And then we have Marconi, who actually does invent radio, who says something very, very similar. He says this in 1913, and of course, in 1914 World War I breaks out.

Jared: Can you tell me a little bit about this concept in the book of dissimilarity cascades?

Nicholas: This concept of the dissimilarity cascades, I think, is very important. Human beings have a bias to like people who they sense are similar to themselves and to dislike people who they sense are dissimilar to themselves. And what we assume is that the more we learn about somebody else, the more we’ll see how they’re like us and therefore the more we’ll like them.

While our instinct to like someone is strong, our instinct to dislike another person is actually slightly stronger. When you start getting more information about somebody, as soon as you see some way that they’re different from you, some way they’re unlike you, you start to put more and more emphasis on those differences. We begin to emphasize how they’re dissimilar to us.

If you wanted to design a media system that would set off dissimilarity cascades, social media is kind of precisely what you design because it encourages people to disclose as much as possible as quickly as possible about themselves. We’re sort of these buzzing, blooming individuals, and if we present ourselves like that to others, they’re going to be overwhelmed and not know how to make sense of us.

Jared: We’re asking guests to recommend a book to our listeners. Maybe it’s a book everybody should read, but nobody is. Do you have anything for them?

Nicholas: If people know Neil Postman, it’s for his famous book Amusing Ourselves to Death. But after that, he wrote a shorter book called Technopoly. It looked ahead to computers and the kinds of things that are online. And I think in many ways, it was even more prophetic than Amusing Ourselves to Death. It’s also a short book, so you don’t have to have a huge attention span anymore to read it.

Jared: Nicholas Carr, thank you for joining us here at The Honest Broker.

Nicholas: Thanks, I enjoyed it.