The Anti-Tech Canon: 30 Books

My reading list for reviving human values in today's digital desert and liberating yourself from tech overreach

Back in 2024, I felt an urgent need to challenge the new doctrine of techno-optimism. This ideology told people to shut up and keep scrolling.

Silicon Valley would build utopia for us. We just needed to stare into those tiny screens 24/7, download all the apps, and upload all our private information.

They would do all the rest.

Please support my work by taking out a premium subscription—for just $6 per month (even less if you sign up for a year).

Around that time, some tech leaders started sharing reading lists. These were mostly filled with garbage books—banal pop psychology, sycophantic tech bro bios, and padded ‘big idea’ screeds churned out by Gladwell-ish gladhanders.

I found this alarming. I don’t tell these people what to code. Why were they telling me what to read?

But after thinking it over, I decided that there might be a positive side to this. After years of mocking the humanities—learn to code was their mantra—the Hollow Men were finally saying learn to read.

This was the beginning of wisdom. Yes, they did need books. But they needed better books.

Let me be blunt: You won’t learn about those better books from tech CEOs. Many of them are very smart—I spent 25 years in Silicon Valley and know that from firsthand experience. But right now the tech world needs an infusion of humanistic thinking and a larger cultural perspective.

And that’s not something that Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk or Tim Cook can deliver.

You need to go outside the tech echo chamber to find this larger wisdom. I’m talking about the real thing—holistic and healing and with the deepest of roots.

There is no app for this.

Back then, I wrote the following:

There’s a resistance to the notion that philosophers or humanists or artists or spiritual individuals with large souls have anything to offer in this debate. So they are excluded from the conversation.

Tech is treated like a closed universe, operating by its own rules.

You might think this isn’t a big deal. After all, who cares what books tech leaders read?

But I have a very different view. I believe this is a deadly serious matter.

Tech is destructive if it operates outside of core human values and holistic, empathetic thinking. Those STEM disciplines are useful, but only when they contribute to human flourishing.

Few things would do more to improve our culture and society than a shift in the tech worldview—away from grasping and control and the will to power. Imagine how much we would benefit if the tech community had different values, more compassionate, constructive, and centered on the users (not the makers) of all those devices and apps.

All that can start with a reading list

I have now updated and expanded that reading list. And I’ve also removed it from behind the paywall where it has been hidden from view.

A Humanistic Tech Canon: 30 Books

FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2024. UPDATED AND EXPANDED IN 2025

By Ted Gioia

Here are 30 books from outside the Silicon Valley echo chamber. They critique tech from a humanistic standpoint.

The goal here isn’t destroying or denouncing technology. We just want to put it to good use—for the benefit of its users. These works are the best guides I’ve found for achieving this.

I’ve discussed some of these books elsewhere (click on the links in the titles). In other instances, I’ve written unpublished essays on them that I plan to share with you in the future.

In any event, I will have more to say about these authors and their core ideas. These are my essential sources for a surviving in a broken technocracy.

I list them here in chronological order:

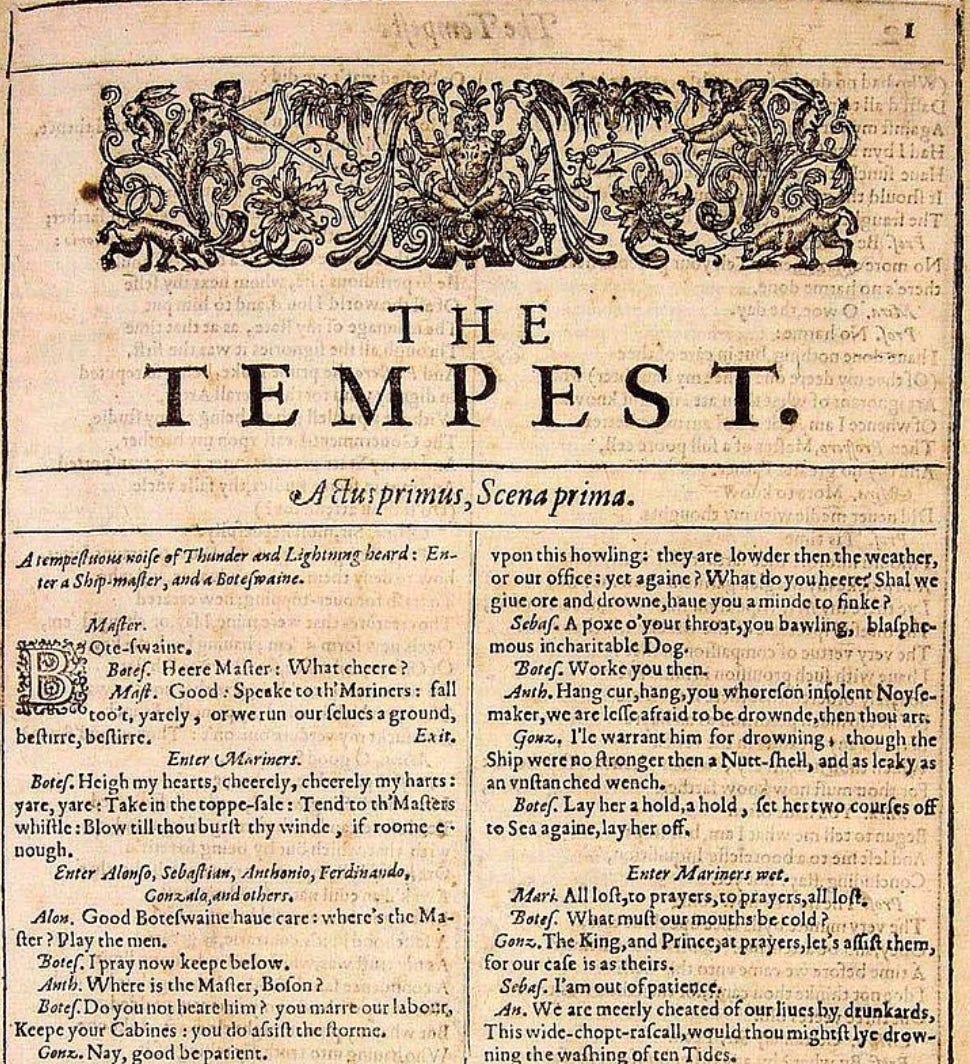

William Shakespeare: The Tempest (1611)

In Shakespeare’s final play, he offers the prototype of a leader and innovator in the character of Prospero—based, many critics believe, on the playwright himself. Prospero’s wizardry brings great power, but also responsibility, perhaps more than he can initially handle.

But a story that begins with an unfettered quest for knowledge and grasping after power, ends up as a celebration of imagination, harmony, and reconciliation. This is a very wise work, and somebody should hand out copies on Palo Alto street corners.

Mary Shelley: Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818)

Dr. Frankenstein is the quintessential tech entrepreneur—striving in his lab to create a breakthrough prototype, stitched together one piece at a time. It’s a shame he has to rob graveyards to get his bits and bytes. But when ends justify the means, anything goes—and, hey, his version 1.0 is a total monster.

In other words, Dr. Frankenstein is the exact opposite of Prospero in Shakespeare’s play. If I were teaching a class for Stanford’s entrepreneurship program, I’d assign a compare-and-contrast paper.

Two hundred years after its publication, Frankenstein is still our best introduction to the responsibilities of the technocrat, and the price we pay when innovation runs ahead of our moral thinking.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Faust (1832)

Forget those fawning tech bios, and consider instead Dr. Faust—who is so excited by knowledge and progress that he sells his soul for them. I really expected to see him on the Forbes billionaire list. It’s too bad that things went sour before the IPO.

John Ruskin: The Nature of Gothic (1853); Unto This Last (1860)

Ruskin praises the technology that built the Gothic cathedrals—and for the most amazing reason. He loves the Gothic worldview because it allowed workers to express their own creativity in the finished work. These artisans still speak to us today in every gargoyle and curlicue.

Ruskin’s The Nature of Gothic thus offers a completely different way of conceptualizing organizations and enterprises—from a genuinely human standpoint.

Seven years later Ruskin published Unto This Last, which offers a similar critique of economics from a caring, ethical perspective. These are essential works for anyone who wants to analyze utilitarian tech stances from the more people-centered perspective of the humanities.

Charles Dickens: Hard Times (1854)

The Enlightenment (1650-1800) delivered rapid industrialization and other economic benefits, but at a terrible human cost. The innovators of that era rarely worried about child labor, slavery, and exploitative work conditions. We are fortunate that the humanists of the 19th century stepped up to counter these abuses.

No writer played a bigger part in this than Charles Dickens. His entire output is informed by a desire for compassionate reform—but the place to start is his 1854 novel Hard Times.

Henry David Thoreau: Walden (1854)

When you finally go on a digital detox out in some hermitage or retreat, this is the book to bring on your healing trip.

Thoreau gave up his smartphone for two entire years. In fact, he abandoned all technology, and pursued a contemplative life in nature at Walden Pond.

You can still do that today, if you dare. For a start, maybe try two weeks—or two days, or perhaps just two hours.

Thomas Mann: The Magic Mountain (1924)

Engineer Hans Castorp finds himself forced painfully outside his comfort zone, as a visitor (and later a patient) in a luxurious tuberculosis sanatorium in the Alps. Here he confronts a tumult of intellectual and emotional currents—the whole modernist 20th century predicament—and all his STEM formulas and analytical skills cannot even begin to grasp their significance.

No novel is more ambitious in showing the limitations and blind spots of the technocrat worldview, and how it cannot operate in isolation from other social currents.

“The fact that Mann sets his novel in Davos, now the favored meeting place of the World Economic Forum, adds a further ironic twist to this already multilayered work.”

The fact that Mann sets his novel in Davos, now the favored meeting place of the World Economic Forum, adds a further ironic twist to this already multilayered work. It’s almost as if Mann saw what was coming in our future.

José Ortega y Gasset: The Dehumanization of Art (1925)

In a tech-driven world, the human element in art is an embarrassing relic from the past. At least some people think so. And nowadays huge businesses are built on the idea of replacing artists with bots.

Ortega grappled with this way of thinking a century ago, and his analysis of the dehumanized aesthetic mindset is eerily relevant right now.

Aldous Huxley: Brave New World (1932)

Imagine a world where people are benumbed by pharmaceuticals, tech-driven entertainment, thought control, and imposed conformity. No, I’m not talking about the Google executive suite—I’m vibing on Huxley’s Brave New World, hatched from his mental hatchery 93 years ago.

This may the single most prophetic sci-fi work of them all. Huxley grasped that you don’t need soldiers to impose tyranny. People will embrace their own degradation and subjugation, if you just make it sufficiently addictive and distracting.

Johan Huizinga: Homo Ludens (1938)

Huizinga was a renegade historian who disrupted the groupthink of his time. (I also love his book The Waning of the Middle Ages, which shows how a rich humanistic society flourished in Europe even before the Renaissance.) In Homo Ludens he is just as provocative—insisting that the most important ingredient in human life is playfulness.

Huizinga loved rituals, festivities, communal gatherings, and all the things we do for sheer fun, not monetary gain. The internet and tech community embraced those same free-wheeling values not long ago, but then it all changed.

If you’re seeking a life-affirming alternative to the grasping utilitarianism of today’s corporate directives, this book is for you.

George Orwell: Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

Yawn—we’re not shocked by this book anymore. Orwell’s account of tech-driven surveillance, brutally employed in the service of authoritarian leadership is now our everyday reality.

But even if the abuses described here are familiar, Orwell still has much to teach us about the psychological and social priorities that underpin his imaginary 1984. It’s just a shame that this is no longer fiction. His command-and-control tech-driven agenda is now the status quo in almost every organization and institution.

There’s heavy irony in the fact that Apple’s most famous TV commercial warned people about precisely this danger. And now Apple is the main source of the “telescreen” (that’s Orwell’s term for it) that does the most harm.

Simone Weil: The Need for Roots (1949)

Simone Weil’s books should come with warning labels. She is constantly tossing out new ideas and agendas—and some of them are odd or worrisome. But her deepest insights are so illuminating that you need to ignore the warnings, and plunge right in.

If she were alive today, Weil would warn us that AI and apps will destroy the rich web of relationship, affinities, and loyalties that allow humans to flourish in their communities. She called these roots—and we’re learning the hard way what happens in a world where millions of people are unrooted or even uprooted.

I plan to write more about Weil in the future. For now, let me point out that this book is rich with implications for those who want to restore human-oriented values in a society where they are getting digitally eradicated.

Martin Heidegger: The Question Concerning Technology (1954)

This is the single best philosophical critique of technology you will ever read. Be forewarned: Heidegger’s prose is dense and difficult. But when he describes how tech wants to turn everything into raw material for its own reframing of the human world, you will be stunned by his prescience. He writes as if he has been eavesdropping on board meetings at Meta and OpenAI.

Hannah Arendt: The Human Condition (1958)

This book also feels like it was just written today. In the opening paragraphs, Arendt talks about techies who want to build spaceships, create virtual reality, and dominate society with thinking machines. But she wrote all this in the 1950s.

She offers an acute diagnosis of the current malaise, and provides a deeply textured alternative way of thinking about the human condition—offering an actual playbook for a creative, purposeful life.

F.R. Leavis: Two Cultures? The Significance of C. P. Snow (1962)

The feud between F.R. Leavis and C.P. Snow ranks among the most intense intellectual battles in modern history. Their debate got so nasty that Leavis’s publisher needed to get a signed release from Snow before they would publish this book.

And the subject of the debate? It was on the relative value of tech versus humanities.

You can hardly imagine such a dry subject creating a firestorm in the early 1960s. But it did—and the aggressive dueling between these two thinkers is more important than ever right now. We would do well if they taught about it in tech and managerial programs. That won’t happen—but Snow’s and Leavis’s heated exchanges are available for anyone who cares to read them.

Frank Herbert: Dune (1965)

What do you fear most from Silicon Valley? Maybe anti-democratic centralization of power? Or cult-like behavior? Or ecological exploitation and ultimate collapse? Or spiced-up technocrats on mind-altering drugs making big decisions?

Herbert deals brilliantly with all these themes in his epic novel Dune—and lots more. There are even huge sandworms here doing the exact same work as Elon Musk’s Boring Company.

You may think that the author was writing about an imaginary desert planet. But Frank Herbert was an editor in San Francisco when the tech thing took off. He learned from what was happening around him—and just pretended that it was all make-believe.

Trust me, this is one of the most underrated literary works of the 20th century. It deserved the Pulitzer in fiction back in 1965. I won’t even mention the forgettable novel that got the prize instead.

Philip K. Dick: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (1968)

What happens when tech gets so advanced you can’t tell the difference between human and machines? For the big tech companies today, that’s their business plan, but for Philip K. Dick it was dystopia.

If robots ever do take over society, this will be the first book they burn.

Gregory Bateson: Steps to an Ecology of Mind (1972)

Gregory Bateson was one of the most wide-ranging intellectuals of the 20th century, and a hero of the counterculture. But his specialty was the interplay between technology, society, psychology, and the environment.

We need an ecology of mind today, and especially among the tech leadership. This expansive work is filled with insights on how to attain it.

Annie Dillard: Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974)

This is the best book about living in nature since Thoreau’s Walden—a loving account of how to flourish without digital interfaces, in embodied, empathetic relationship with the real world.

Dillard is also a remarkable prose stylist. Even if you aren’t ready to lock up your smartphone, you should read this book just for the quality of the writing.

Michel Foucault: Discipline and Punish (1975)

Foucault made a specialty of studying the hidden history of controlling institutions—prisons, mental asylums, hospitals, etc. He showed how they pretend to operate on benevolence and service, but actually work to maximize power and centralized authority. Their tools are data and surveillance.

The worldwide web didn’t exist when Foucault wrote this book, but it’s evolving into a kind of utilitarian’s Panopticon prison just like the one he describes in its pages.

William Gaddis: JR (1975)

Just imagine a youngster launching a huge business—and doing it all with just a phone. No, I’m not talking about Sam Bankman-Fried or Vitalik Buterin or somebody from Peter Thiel’s youth launching pad.

Instead, I’m referring to the eleven-year-old hero of William Gaddis’s cranky postmodernist novel JR. Back when it came out in 1975, readers laughed at this improbable story. Little did they know all this was in our future.

Jean Baudrillard: Simulacra and Simulation (1981)

What happens when all reality is marginalized, and fake things start imitating other fake things? The result is the ultra-vapid world of the hyperreal, deconstructed by Baudrillard in Simulacra and Simulation—a work much beloved by grad students in critical theory.

Alas, Baudrillard’s notion of simulation—a bogus reality built on nothing, with no origin or actual referent—is no longer just a trendy concept for PhDs. It’s the driving force in today’s Matrix-inspired tech.

Neil Postman: Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985)

Neil Postman doesn’t mention the iPhone anywhere in this book. How could he? Smartphones didn’t exist back when he wrote Amusing Ourselves to Death. But make no mistake, this is the single most incisive critique of screen-driven culture ever written.

Back in 1985, Postman was worried about television. It seems quaint now—all this brouhaha about the boob tube. But Postman saw it as more than just idle entertainment for couch potatoes. He feared the consequences of replacing concepts, texts, and reading with screens, images, and watching.

He believed that reading and writing challenge our thinking and build our cognitive skills. But images deaden them. Forty years ago, he feared that raising a whole generation on screen interfaces might put everything at risk—education, democracy, even our mental capacities.

The dangers he saw in TV have been amplified a hundredfold by the tiny screens we carry with us in our pockets. So the man who never lived long enough to use a smartphone turns out to be our single best guide in understanding it.

Kazuo Ishiguro: Never Let Me Go (2005)

Sometimes pushing technology forward requires the destruction of living, breathing people. In extreme cases, the trade-offs are obvious, as in the Manhattan Project. But in other instances the costs are indirect, or hidden from view.

There’s a lot of that going down right now. And the scariest thing is when the people doing all the damage just smile and pretend this is fine—like a coffee-drinking meme dog in a burning building.

Nobel laureate Ishiguro believes this is not fine, and instead nurtures our empathy in this deeply moving novel. I won’t say more, because I don’t want to give away plot spoilers—so just read the book.

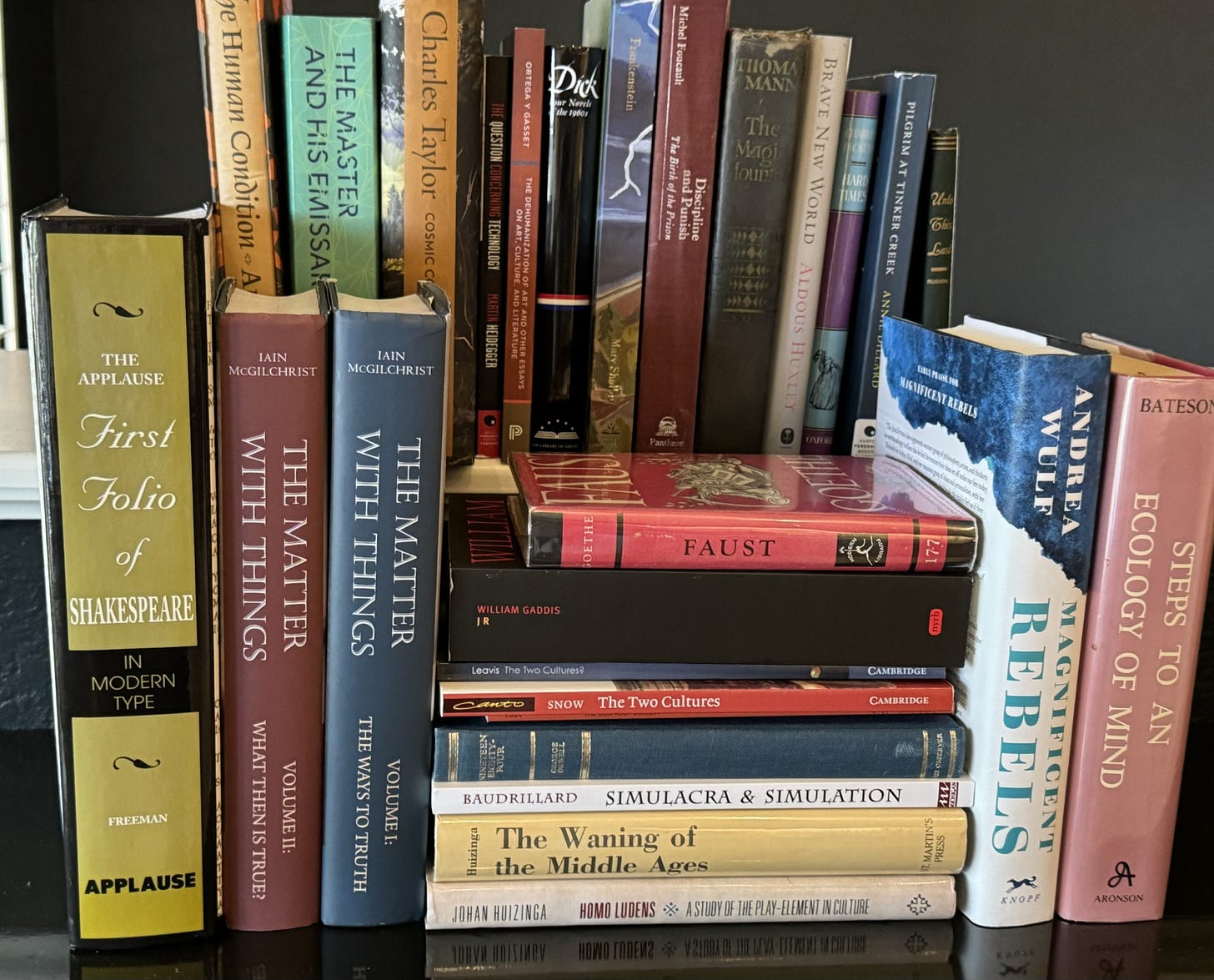

Iain McGilchrist: The Master and His Emissary (2009)

I believe that Iain McGilchrist ranks among our half dozen most important living thinkers. His ability to bring together science, humanities, history, and philosophy at such a granular (but interconnected) level is impressive—and about a hundred steps ahead of the empty postures in all those pop technology books about macrotrends or life hacks.

McGilchrist grasps the risks to society from the left-brain obsession with calculating, controlling, and dehumanizing that pervades the dominant worldview. This book was filled with insights when it was published fifteen years ago, but it actually gets more important with each passing year.

His followup work The Matter with Things (2021) pushes his critique even further. It’s a massive undertaking—the bibliography alone is almost 200 pages! But McGilchrist has big goals—he is taking on an entire dysfunctional system. We do well to pay attention.

Paul Feyerabend: The Tyranny of Science (2011)

In my early 20s, I first read Paul Feyerabend—and was horrified. I had been imbibing the philosophy of science from Thomas Kuhn, Karl Popper, Imre Lakatos and other logical and reasonable people. But Feyerabend was like a voodoo doctor at the Mayo Clinic (almost literally, if you know his worldview).

His book Against Method (1975) was one of the most disruptive books I’ve ever read. And for many years I mocked it. But now, in an age where scientific studies fail to replicate and tech companies pursue progress that looks like regress, I realize that Feyerabend knew exactly what he was talking about.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that this Austrian-born thinker moved to California, and saw the tech revolution firsthand over the course of three decade. The Tyranny of Science, published posthumously, is a plea for a more pluralistic approach to science, and calls out the subtle (or not-so-subtle) will to domination and control that too often drives supposedly disinterested research.

Byung-Chul Han: The Burnout Society (2015)

Multitasking isn’t progress, Byung-Chul Han warns us—it’s what animals do in the wild. It’s a way of life for people in survival mode. And the multitasking mantra of “You can do everything” soon collapses into “I can do nothing.”

You need to read this book if you want to understand how pervasive digital tech is contributing to rising rates of depression, mental illness, and other psychic disorders.

Andrea Wulf: Magnificent Rebels: The First Romantics and the Invention of the Self (2022)

The single best role model for our thought leaders today is the Romanticist movement that transformed European culture, circa 1800—and later spread to America and elsewhere. The Romanticists offered a persuasive alternative to the profit-maximizing industrialization and rationalistic, atomistic thinking of the Enlightenment.

They understood that human beings matter. The natural world matters. Our psyches and souls matter. They were artists and visionaries but also reformists who helped end slavery, child labor, and other abuses.

And guess what? The Western economies actually grew faster after those dreamy-eyed Romanticists made their reforms—because holistic thinking really does produce beneficial results for almost everybody.

Andrea Wulf has written the single best account of how this movement got launched and spread like wildfire through society—combining biography, philosophy, history, and cultural criticism in a very readable book.

I believe that something similar is going to happen again—and sooner than anyone realizes.

Charles Taylor: Cosmic Connections: Poetry in the Age of Disenchantment (2024)

What would the world look like if it turned to poetry—not apps and devices—for an upgrade? Philosopher Charles Taylor points the way in this brand new book.

Taylor recently celebrated his 93rd birthday, so this will probably be his last major work. But what an inspiring capstone. He actually takes the arts seriously as a springboard for the fully realized life. I’ll choose that over a chatbot any day of the week.

That’s my list—30 mind-expanding books from the wisest people I can find.

Don’t dismiss them. If important people actually read these works and took them seriously, the ground might start shaking in Silicon Valley. And I’m not talking Richter scale, but something even bigger.

If you have other titles to add to this syllabus, tell us in the comments.

Pretty detailed list. You should also have Ted Kaczynski’s Industrial Society and its Future. Even though he committed terrorist acts and he died in prison where he belonged, the manifesto that was first published in the Washington Post in 1995 is worth reading, especially regarding how technology can have a negative effect on human individuals. Some of the quotes are quite relevant today sadly especially with the mental health crisis with kids and screens.

“The system does not and cannot exist to satisfy human needs. Instead, it is human behavior that has to be modified to fit the needs of the system.”- Ted Kaczynski

“The concept of “mental health” in our society is defined largely by the extent to which an individual behaves in accord with the needs of the system and does so without showing signs of stress.”- Ted Kaczynski

Intriguing list, thanks for sharing! Many of the books I haven’t read although they were already on my list and others haven’t even been in it.

Just as a comparison, here s what chatgpt 4.0 recommends based on your intro and framing (quite some overlaps and interesting alternatives)😉

Reading List: Toward a Human-Centered Tech Ethic

I. Philosophy, Ethics & Moral Imagination

1. Albert Camus – The Myth of Sisyphus

A call to embrace meaning and dignity even in an absurd world.

2. Simone Weil – Gravity and Grace

Spiritual clarity in the face of power, violence, and materialism.

3. Martin Buber – I and Thou

A foundational text on dialogue, encounter, and relational life.

4. Hannah Arendt – The Human Condition

What it means to act, think, and create meaningfully in a world of machines.

5. Alasdair MacIntyre – After Virtue

On the collapse of shared moral systems—and what we can recover.

6. Martha Nussbaum – Creating Capabilities

A human development framework based on dignity and flourishing.

7. Byung-Chul Han – The Burnout Society

Modern tech capitalism as a system of internalized exploitation.

8. Charles Taylor – The Ethics of Authenticity

Resisting flattening forms of instrumental rationality.

9. Ivan Illich – Tools for Conviviality

Designing technologies that empower rather than dominate.

10. Paul Feyerabend – The Tyranny of Science

On scientific arrogance and epistemological pluralism.

⸻

II. Systems Thinking & Complexity

11. Gregory Bateson – Steps to an Ecology of Mind

Cybernetics, feedback, and the need for ecological intelligence.

12. Donella Meadows – Thinking in Systems

Practical insight into how complex systems behave—and fail.

13. Iain McGilchrist – The Master and His Emissary

How brain hemispheres reflect competing worldviews—analytic vs. holistic.

14. Fritjof Capra – The Web of Life

Re-envisioning biology and society as interdependent networks.

15. Nora Bateson – Small Arcs of Larger Circles

A poetic systems thinker’s view on interwovenness and grace.

⸻

III. Spiritual and Indigenous Wisdom

16. Robin Wall Kimmerer – Braiding Sweetgrass

A botanist and indigenous thinker reclaims reciprocity and reverence.

17. Black Elk – Black Elk Speaks

Lakota wisdom on vision, ritual, and interconnection.

18. Thomas Berry – The Dream of the Earth

A cosmologist’s call for an ecological spiritual awakening.

19. Bill Plotkin – Soulcraft

Technology may serve ego, but soul needs myth, depth, and wildness.

20. Thich Nhat Hanh – The Art of Living

How presence and compassion can shape every field—including tech.

⸻

IV. Literature as Deep Critique

21. Fyodor Dostoevsky – Notes from Underground

The limits of reason and the soul’s revolt against cold rationalism.

22. Aldous Huxley – Brave New World

Techno-utopia as dehumanizing dystopia.

23. Mary Shelley – Frankenstein

The original myth of creation without care, innovation without ethics.

24. Kazuo Ishiguro – Klara and the Sun

An AI companion raises human questions machines can’t answer.

25. George Orwell – 1984

Surveillance, data, and power in their most terrifying alignment.

⸻

V. Critical Tech and Future Thought

26. Shoshana Zuboff – The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

How tech extracts human experience as raw material.

27. Douglas Rushkoff – Team Human

Why we must reclaim human agency in a digital world.

28. Tristan Harris – The Ledger of Harms (public paper + talks)

How to reorient tech design toward ethics and wellbeing.

29. Ruha Benjamin – Race After Technology

How algorithms reinforce systemic inequality—and how to resist.

30. Jenny Odell – How to Do Nothing

A quiet manifesto for attention, place, and reclaiming human time.

⸻

Optional Bonus Categories

• Design ethics: Victor Papanek – Design for the Real World

• AI philosophy: Brian Cantwell Smith – The Promise of Artificial Intelligence

• Poetic insight: David Whyte – Consolations

• Futures thinking: Bayo Akomolafe – These Wilds Beyond Our Fences