"Multitasking Isn't Progress—It's What Wild Animals Do for Survival"

I grapple with philosopher Byung-Chul Han’s view that we now live in a "Burnout Society" where too much positivity has spurred an unprecedented psychic crisis

I plan to write a series of posts outlining some unconventional or dissident conceptual frameworks I’ve found useful in understanding contemporary society.

These aren’t the usual tired ideas or dead metaphors already familiar to us. I won’t even mention those stale truisms, because you already know every one of them—in fact, we would all probably be better off forgetting them.

Fewer things are more destructive than a dead-end concept. They are much like dead-end roads—they take you on a trip to nowhere. They provide an illusion of motion, but actually bring you further away from any useful destination.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

The concepts I’m sharing are less familiar, and all the more valuable for that reason. They have forced me to look at everyday situations in new ways, requiring me to challenge some of my own preconceptions and attitudes. Even when they fail to encompass all of a particular reality, they still add value by disrupting the labels and assumptions that I use—and all of us use—to navigate through day-to-day life.

In this installment, I want to focus on Byung-Chul Han’s concept of the Burnout Society.

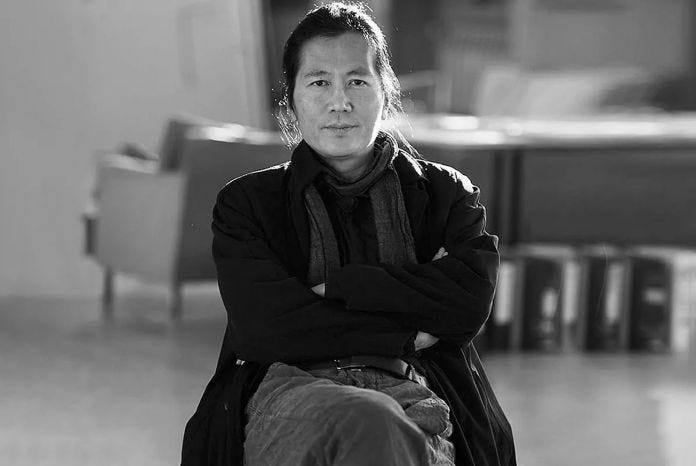

Han is one of the most significant German philosophers of our time, but his background is unusual. He was born in Seoul, South Korea in 1959, and studied metallurgy before moving to Germany to immerse himself in philosophy, theology, and literature. He received his doctorate in 1994, writing his dissertation on Martin Heidegger. His philosophy career didn’t start in earnest until his forties, yet he has now published at least twenty books.

Until recently, Han gave no interviews. In a celebrity-driven culture, he refuses to play the game, remaining stubbornly reluctant to discuss his own life and personal background. But that hasn’t prevented him from gaining a large audience, much broader than you might imagine a German philosopher attracting in the current day. His lectures draw a capacity audience, and his ideas are now crossing over into other disciplines. In particular, a number of people in the art and culture world have started to pay close attention to his concepts and opinions.

Those who have read my book Music; A Subversive History may recall my use of Han’s aesthetic concepts—notably his view that the cult of smoothness is the defining quality of contemporary art. He applies this concept to everything from the design of the iPhone, with its comforting smooth contours, to the Brazilian bikini wax, which aims at a similar endpoint on our bodies.

In this instance, I want to focus on a different concept, namely Han’s notion that we are living in a “Burnout Society” that causes a wide range of characteristic dysfunctions and ailments. These are difficult for society to address because the assumptions built into our inquiries are actually causing these problems.

What follows below is mostly from Han, but reframed and focused by some of my own ideas.

THE BURNOUT SOCIETY

Everywhere around us we see the signs: depression, burnout, hyperactivity, anxiety, self-harm. Sometimes the disorders get classified as medical syndromes with impressive acronyms, such as ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder) or CFS (Chronic Fatigue Syndrome) or BPD (Borderline Personality Disorder).

In other cases—a suicide or fatal breakdown, for example—things have gone too far for even medical intervention. All the acronyms in the world won’t help you then. But in every instance, something similar can be seen: the victims are at war with themselves.

That’s misleading, Byung-Chul Han would say. They only seem to be the instigators of their problems, which are coming from the burdens of a society overdosing on positivity and self-directed achievement. You can’t solve a problem when it’s caused by the very methods you use to solve problems. And that’s at the root of our growing crisis of self-destruction.

You can do anything!

That’s the mantra, and you hear it everywhere. All the messages circulating in our society seem to converge on that same imperative.

But this soon turns into: You must do everything. The symptoms are everywhere—fitness programs, self-help podcasts, inspirational quotes on social media, vitamins and nutritional supplements, constant proclamations about self-actualization, weight-loss fads, life coaches, and countless other schemes for improvement. No boss would ever be as tyrannical as we are to our souls and selves.

We brag about multitasking, but Han warns that this isn’t an advance—in fact, it’s the opposite of progress. “Multitasking is commonplace among wild animals,” he writes. “It is an attentive technique indispensable for survival in the wilderness.”

Wild animals must always be wary and cautious—danger is ever present—so they can never focus entirely on a single task. Their vigilance is constant, and covers the full spectrum of the world at hand. Our own lives are now much the same. Video games even help train youngsters in practicing this modern mindset, producing a “broad but flat mode of attention, which is similar to the vigilance of a wild animal.”

This wild animal mindset explains many other dysfunctional aspects of modern life. “For example, bullying has achieved pandemic dimensions,” Han writes. Instead of pursuing a simple, coherent vision of the good life, people feel they are in a never-ending race with both themselves and others—with the result that even friends and family feel the spillover pressure from the mandate to achieve.

Han sharply disagrees with Michel Foucault, who famously depicted modern society as based on a disciplinary model—and looked at prisons, mental institutions, hospitals, and other places of confinement as paradigmatic examples of the human condition. This might have been true in the past, Han admits, but today, the pressure on individuals comes from the pervasive need for self-actualization, not external discipline, which has weakened to the point of irrelevance.

Even our psychological models need to change in the face of this shift. Freud’s conceptual framework, Han claims, was built on the model of disciplinary society, and is filled with metaphorical “walls, thresholds, borders, and guards.” Perhaps that was a valid approach in Vienna a hundred years ago, when Freud developed his worldview. But the problem today isn’t thwarted desires, rather desire opened to the point of infinity.

In other words, the enemy is hard to find because we have internalized it. We are told to be “entrepreneurs of the self.” We can’t blame the boss or master or patriarch any more, because we play those roles in our own lives, constantly whipping ourselves up to greater and greater levels of achievement—or, increasingly, falling into some psychical or nervous disorder because we feel incapable of keeping up with the pace of this unending round-the-clock game.

The word that best describes this chronic situation is burnout. And it’s a word we’ve grown used to hearing often nowadays. And will continue to hear, because everything in both our public and private lives converges on it.

Even forms of entertainment, which should be a break from the achievement mindset, incorporate it. You need to level up in the video game. You need to add more followers on Instagram. You need to improve your performance at a sport or hobby. You need to check off more items on some bucket list of films seen, books read, landmarks visited, etc.

“One’s many friends on Facebook would offer further proof of the late modern ego’s lack of character and definition,” Han writes. Here, too, the prescribed goals tend to infinity. A truly fulfilled life probably requires two or three genuinely close friends—in contrast, the hundreds or thousands who play that imaginary role for us on social media provide something very different.

Even sex gets reduced to the contemporary practice of scrolling quickly through images on apps—again taking on the quality of endless choice. Thus even in the most intimate moments of our life, our quest for true connection with kindred spirits, the achievement mandate dominates the horizon in every direction.

“Even if you work inside the system, you don’t have to let the system work inside of you.”

In this kind of culture, everything takes on an insatiable non-stop quality. Instead of enjoying a mindless sitcom, you binge watch an entire season of shows. Instead of enjoying dinner, you focus on sharing photos of your masterful culinary efforts on social media. The most banal tasks now become occasions for live-streaming and building your personal brand.

And emerging technologies will only aggravate the situation. If you worry that the Internet cuts us off from reality, wait until you see what immersion in the so-called Metaverse brings. Here the quest for actualization without limits will be literally designed into the fabric of our experiences.

The dominant ideologies fail to grasp the essence of this crisis because, Han claims, they are built on the notion of external conflict with outside enemies. In truth, we have all seen an extraordinary decline in actual battles of this sort during our lifetimes—and that can be demonstrated in many ways. Here’s one:

I could share a dozen other charts that convey the same truth. There aren’t as many external enemies as there once were—whether you measure it in terms of labor strikes, duels, mob wars, whatever.

But we have a need to combat enemies even when the actual battlefields are disappearing. This leads to a panoply of dysfunctional behavior patterns—many of them resulting in battles on an individual basis. My neighbor or family member becomes a substitute target for the actual foes our ancestors met in open combat. And just consider how much we still obsess on borders and boundaries even in peaceful times.

But these are small matters, Han suggests, compared to the most dysfunctional substitute victim of all, namely ourselves. This is a person we can subjugate and oppress round-the-clock, and there’s no way for the target of our hostilities to escape. This is the essence of the Burnout Society.

Han wrote his book several years before the COVID crisis, but he addresses viruses at the very beginning of the first chapter. The concept of a virus is almost a magnet for a mindset that wants to battle external enemies. Even before the pandemic, the media loved to write about computer viruses or viral trends. Han could have predicted that a genuine virus would become a focal point for everybody’s attention—not just a public health issues, but a media phenomenon of unprecedented intensity in our lifetimes. And that’s exactly what has happened.

But a virus isn’t a sufficient enemy—at least in terms of channeling the violent impulses at large in society. You can’t punch a virus in the face or grab it by the throat. When a better outlet isn’t available, the violence turns inward. The result is spiraling cases of depression, fatigue, burnout, and suicide.

How do we get out of this?

Han seems to sense a spiritual void at the center of the Burnout Society, and plays around with the idea of “an imminent religion of tiredness.” But this release only comes, according to him, when we are so exhausted that we achieve some mellow state of tolerance and acceptance. Frankly, I don’t see many signs of that on the horizon.

In this regard, I find other thinkers (Charles Taylor, René Girard, Gregory Bateson, etc.) as more compelling than Han—who is better at diagnosis than the cure.

I’d add one more comment: I suspect that solutions here demand a kind of counterculture capable of resisting the monolithic mindsets causing burnout—and the sad fact is there is no genuine counterculture right now. It was once fashionable to opt out from the groupthink and reconstruct your own life in a free-spirited or even openly dissident way. But the groups and power brokers have gotten less tolerant of dissent nowadays, and it’s harder to find a space for self-invention outside their purview.

Not too long ago, if you didn’t like the system you could drop out—there was even an aura of positivity to the notion of the dropout. Some of most creative people of the 20th century were dropouts, from Walt Disney to Jack Kerouac. It was a thing bohemians and beatniks and hippies did. But when is the last time you saw a bohemian or a beatnik?

“There are no Walden Ponds or hermitage retreats anymore—even the off-the-grid spots are now on the grid.”

And even if you wanted to drop out nowadays, could you? You are identified, tracked, networked, and classified everywhere you go, at every moment of your day. Never in history has it been harder to find a fresh start, a clean slate, or a place to march to the beat of your own drummer. There are no Walden Ponds or hermitage retreats anymore—even the off-the-grid spots are now on the grid.

Only a rare person finds a personal path to serenity in this kind of culture. That suggests that the larger solution must be to fix the society before we can heal most of the people. I don’t underestimate the difficulty of that, but that doesn’t mean I can’t see the desperate need. In the meantime, the only genuine responses will happen at the level of the individual or the small group.

I can’t stress this enough: You do not need to walk in lockstep with everybody else. You aren’t required to accept blindly the dominant values of your society. Even if you work inside the system, you don’t have to let the system work inside of you. No law requires that. It’s not part of the terms and conditions of being a human being.

I wish Han had paid more attention to that fact. But it’s crucial and worth repeating: Even if you work inside the system, you don’t need to let the system work inside of you. And if you summon up the boldness to go in a different direction, others might even surprise you by following along.

Makes me think of a story: [When Vonnegut tells his wife he's going out to buy an envelope] Oh, she says, well, you're not a poor man. You know, why don't you go online and buy a hundred envelopes and put them in the closet? And so I pretend not to hear her. And go out to get an envelope because I'm going to have a hell of a good time in the process of buying one envelope. I meet a lot of people. And, see some great looking babes. And a fire engine goes by. And I give them the thumbs up. And, and ask a woman what kind of dog that is. And, and I don't know. The moral of the story is, is we're here on Earth to fart around. And, of course, the computers will do us out of that. And, what the computer people don't realize, or they don't care, is we're dancing animals. You know, we love to move around. And, we're not supposed to dance at all anymore.

Hi Ted,

Very thought provoking... brings up an example in my own life... I started surfing at age 40 (I am nearly 60 now).

At first it was just great to be out in the ocean doing this magical thing.. riding transitory energy.

But recently I have found myself looking at coaching videos.. how to improve your surfing....

Why???? I don't compete????

It is just a built in idea in our current lives that you should improve at everything you do.