Why is the Oldest Book in Europe a Work of Music Criticism? (Part 1 of 2)

Here's the opening of chapter one from my new book 'Music to Raise the Dead'

Below is the first chapter of my new book Music to Raise the Dead—which, as promised, I’m publishing on Substack.

My plan is to publish one chapter per month on The Honest Broker. Chapter one will be shared in two installments—I’m releasing the first half of the chapter today, and will publish the rest very soon.

To give you the larger context, here’s a link to the book’s prologue and introduction—and below is the table of contents.

Each chapter can be read on its own, or as part of the larger narrative of the book.

MUSIC TO RAISE THE DEAD: Table of Contents

Prologue

Introduction: The Hero with a Thousand Songs

Why Is the Oldest Book in Europe a Work of Music Criticism? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Is There a Science of Musical Transformation in Human Life? (Part 1) (Part 2)

What Did Robert Johnson Encounter at the Crossroads? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Why Do Heroes Always Have Theme Songs? (Part 1) (Part 2) (Part 3)

What Is Really Inside the Briefcase in Pulp Fiction? (Part 1) (Part 2)

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

CHAPTER ONE

Why is the Oldest Book in Europe a Work of Music Criticism?

By Ted Gioia

Greek workers were simply trying to widen the road from Thessaloniki to Kavala. On January 15, 1962, the work crew had arrived at Derveni, a narrow pass six miles north of Thessaloniki, where they stumbled upon an old necropolis.

They didn’t know it at the time, but they had discovered a burial ground near the ancient city of Lete. Judging by the weapons, armor, and precious items, it had served as a gravesite for affluent families with soldiering backgrounds.

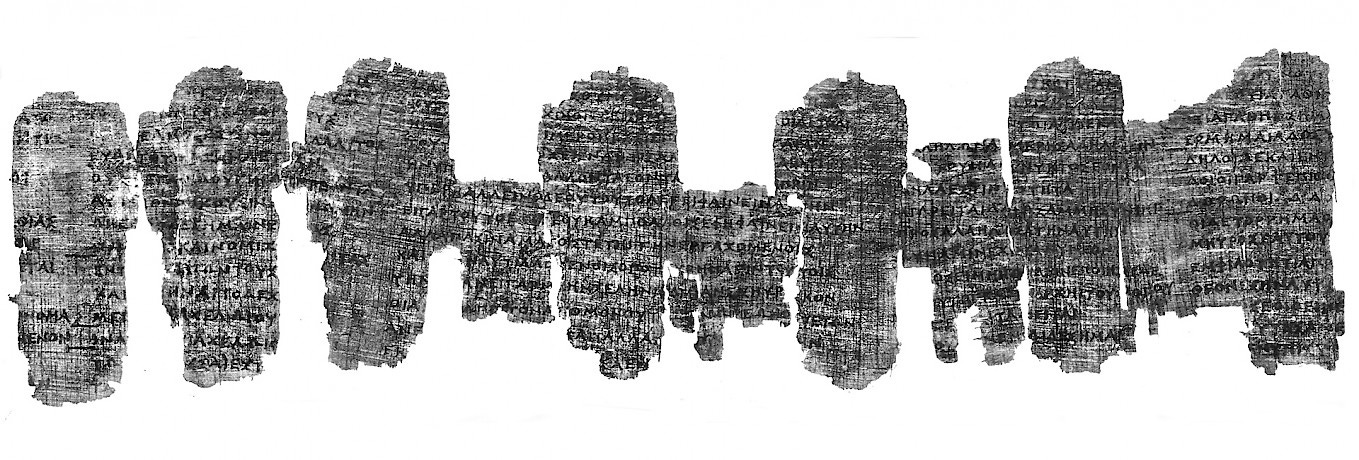

Here among the remnants of a funeral pyre on top of a slab covering one of the graves, they found a carbonized papyrus. Experts later determined that this manuscript was, in the words of classicist Richard Janko, “the oldest surviving European book.”

The discovery of any ancient papyrus in Greece would be a matter for celebration. Due to the hot, humid weather, these documents have not survived into modern times. In this case, a mere accident led to the preservation of the Derveni papyrus—the intention must have been to destroy it in the funeral pyre. The papyrus had probably been placed in the hands of the deceased before cremation, but instead of burning, much of it had been preserved by the resulting carbonization.

Mere happenstance, it seems, allowed the survival of a document literally consigned to the flames. And what was in this astonishing work, a text so important that its owner wanted to carry it with him to the afterlife?

Strange to say, it was a book of music criticism.

But this charred papyrus contained a very unusual type of musicology. To start, it analyzed a song by a composer who didn’t exist, or so we’re told. Even by the standards of reclusive star musicians of our own time, that’s quite a disappearing act.

To add to the mystery, the expert analyzing the song, the author of our Derveni text, was also anonymous, but clearly was a sage consulted for his deep theoretical and practical knowledge—expertise that gave the possessor a quasi-magical power—of hymns by Orpheus, the composer of the song in question. But most unusual of all were the claims made about this music—which, as we shall see, go far beyond the usual boundaries of song analysis and interpretation.

Adding to the mystery, excavators also found in Derveni some of the oldest pharmaceuticals and medical tools ever identified in the Western world. Trying to put together the details is challenging—or even bizarre. What we seem to have here is the resting spot of rare individuals who were warriors and priests and healers—empowered by special songs with their own esoteric musicology.

If this was, in fact, the birth of music criticism, it’s unlike any kind practiced today. Lester Bangs at Cream or the gnarliest punk ‘zines seem conventional by comparison.

Yet, in some ways, all this was fitting. Orpheus was, without question, the most famous musician of antiquity, although also the most peculiar. He too was an adventurer and a healer and a musician. His songs were so remarkable that they charmed not only people, but also animals and trees, and even Hades, ruler of the Underworld, who rewarded Orpheus by allowing him to bring his dead wife Eurydice back to the realm of the living.

You’ve probably heard that story at some point. It’s one of the most famous tales in history. Orpheus literally knew music to raise the dead.

But this beguiling myth, still widely told today, could hardly be an actual historical event. You can’t really visit the Underworld, can you? Songs can’t really raise the dead, can they? That’s obvious, no? Maybe to us, it is—but 2,500 years ago, Orpheus was considered every bit as real as Homer, Hesiod, and other respected authorities of antiquity.

I’ve been researching the myth of Orpheus for almost 25 years now, and I’m not so sure he is merely a myth. Certainly the author of the Derveni papyrus was absolutely convinced of his reality. As far as I can tell, everybody back then believed that both Orpheus and his music were incontestably real, and capable of doing things that, today, would fall under the domain of medicine, or science, or philosophy, or even magic.

We would love to hear music of that sort, wouldn’t we? And the Derveni papyrus actually shares parts of a hymn, praised not for its beauty or artistic merits, but because of its extraordinary powers. In other words, the Derveni author was offering to teach the secrets of a kind of music much like that famous Orphic song that had brought a dead soul back to life. You can now understand why someone would want to bring this music to the next life—it was simply too good, too powerful to leave behind.

But let me emphasize, here at the outset of our journey, that this is a much bigger issue than just one man and his magical songs. A key argument of this book is that the shape of Western society even today is the result of a battle in worldviews that took place 2,500 years ago. On the one side, you had the proponents of logic, rationality, and philosophy, and they defeated their opponents who put their faith in songs.

It seems like an unfair battle. How can music ever be more powerful than logic? But Plato—and the other leading ancients who laid the groundwork for our rational and algorithmic society—feared music for a good reason. They saw the hypnotic effect of the epic and lyric singers on the masses. For centuries, people learned life skills from songs. They preserved history, culture, and the entire mythos with songs. They tapped into their own deepest emotions with songs. They celebrated every life milestone and ritual with songs. They reached out to the gods themselves with songs. Above all, they used this music to secure personal autonomy and what today we would call human rights. So we should not be surprised that Plato, Aristotle and the other originators of Western rationalism had to displace this dominant worldview of their ancestors—mythic, magical, musical—in order for them to create a more rigorous, disciplined, and analytical society.

They won that battle, and we live with the consequences today in our algorithm-driven culture. As a result the richest and most influential musicology in the history of human society has been mostly forgotten. The Derveni papyrus and the tradition it represents is never taught or even mentioned at music schools. But this alternative musicology—which we need more today than ever—hasn’t disappeared completely. Far from it. As we shall see, it still exerts a surprising impact in almost every sphere of human life, but in hidden ways. Alas, the musicians themselves are never formally initiated into its techniques and responsibilities, and won’t learn them unless they discover them by chance. And for the simple reason that even their teachers never learned about them in the first place.

But if this is an amazing kind of musicology, it’s also an embarrassment. Maybe that’s why I’ve never heard a single musicologist mention the Derveni papyrus—although it is arguably the original source in the Western world of their own academic specialty. Things aren't much better in the various academic disciplines of ancient studies, built largely on celebrating the rational and literary achievements of the distant past. For classicists, the claims presented in this papyrus are awkward from almost every angle.

The Derveni author was clearly smart and educated, a seer among the ranks of magi, but hardly operating from the same playbook as Plato and Aristotle—those paragons of logic and clear thinking. At first glance, this sage seems more like those roadside psychics working out of low-rent strip malls, who tell your future and bill twenty-five dollars to your credit card.

But this magical mumbo-jumbo was just a start of the many controversies surrounding the Derveni papyrus. As subsequent events proved, almost every aspect of this ancient text would be scrutinized, disputed, and—most of all—cleansed in an attempt to make it seem less like wizardry, and more like the scripture of an organized religion, perhaps similar to the teachings of a sober Protestant sect, or the tenets of a formal philosophy, similar to those taught in respectable universities.

We will need to sort out a few of these troubling issues, which have considerable bearings on our understanding of the origins of music, and even its potential uses in our own times. But before proceeding, I must point out a disturbing pattern I’ve noticed over the course of decades studying the sources of musical innovation: namely, that many of the most important surviving documents were preserved only by chance, and frequently were intended for destruction—and, when they have survived, they have frequently been subjected to purifying distortions of the same kind involved here.

In fact, it’s surprising how often musical innovators are completely obliterated from the historical record. And if you pay attention you notice something eerie and unsettling: the more powerful the music, the more the innovators risk erasure. We are told that Buddy Bolden was the originator of jazz—but not a single recording survives (or perhaps was ever made). W.C. Handy is lauded as the “Father of the Blues,” but by his own admission he didn’t invent the music, but learned it from a mysterious African-American guitarist who performed at the train station in Tutwiler, Mississippi. In that instance, not only did no recordings survive, but we don’t even know the Tutwiler guitarist’s name.

Even the venerated genres of Western classical music originate from these same shadowy places. Only a few musical fragments survive from the score of the first opera, Jacopo Peri’s Dafne; and Angelo Poliziano’s Orfeo, an earlier work that laid the groundwork for the art form, is even more enigmatic. Not only has none of its music survived, but we aren’t entirely sure of the year it was staged, the makeup of the orchestra, or the names of the musicians who might have assisted Poliziano in the creation of the work. Yet such mysteries are hardly exceptions but rather the norm in the long history of musical innovation, so murky and imprecise and resisting the neat timelines we find in other fields of human endeavor.

Inventors and innovators in math, science, and technology are remembered by posterity, but for some reason the opposite is true in music. If you are a great visionary in music, your life is actually at danger (as we shall see below). But, at a minimum, your achievement is removed from the history books. If you think I’m exaggerating, convene a group of music historians and ask them to name the inventor of the fugue, the sonata, the symphony, or any other towering achievement of musical culture, and note the looks of consternation that ensue, even before the arguments begin.

Of course, old things rarely survive under the best of circumstances, but in the case of musical innovations the deliberate aim is, with disturbing frequency, complete destruction. We see this from the very start, with the earliest singer known by name, the Mesopotamian priestess Enheduanna, who lived more than 4,000 years ago. In 1927, archeologist Sir Leonard Woolley discovered an impressive alabaster disk depicting our first singer-songwriter at work—consider it the ancient equivalent of a gold record honoring a star musician—but this particular disk had been broken into several pieces and looks as if it has been deliberately defaced as well.

Things hadn’t improved much, more than 1,500 years later, when the ancient Greek poet Sappho, usually credited as the originator of lyric song in the Western world, created her most famous works. Classicists were excited when a new Sappho lyric came to light in 2004. Up until then only three complete works had survived, and now a fourth had been found in the wrappings of an Egyptian mummy. This was truly a cause for celebration, but how sobering to consider that the ancients had only saved the poem by chance—their actual intention had been to preserve the mummy!

But authorities didn’t always need to destroy the songs. Cleansing and reinterpreting are more subtle tools, and especially useful when the music deals with the four forbidden subjects: magic, altered mind states, sex, and violence. The Orphic tradition celebrated in the Derveni papyrus dealt with all four of those matters on an intimate basis—an unfortunate situation for those who hope to understand the origins of Western music. In the case of that kind of hymn, the odds against survival were steep.

Not only is music of this sort endangered, but in many instances the musicians too. Orpheus, according to the myth, was torn to bits by angry Bacchic maidens because of his transgressions. And I note that Pythagoras, the most famous successor to Orpheus—and the innovator credited with inventing the tuning systems that define Western music—may have actually died in a fire set by his enemies, Details are obscure and imprecise, because they always are in these cases, but Pythagoras clearly had to go into exile along with his followers, and many of them perished when their house in Croton was burned to the ground by angry locals. Needless to say, that’s a fate far worse than just having your music burned.

In other words, the history of musical innovation overlaps closely with the history of dissidents and their rebellions. Mull over the implications of that connection.

And the story continues, in the same discordant manner, century after century. The inventor of musical notation, the monk Guido of Arezzo (991-1033), was harassed and evicted from his monastery, and eventually sought out the protection of the Pope. Saint Benedict, who developed a system of chanting still practiced among monastic orders today, is now venerated as both a musical and religious innovator, but he barely survived several poisoning attempts during his tumultuous lifetime. The emergence of counterpoint in European music was accompanied by a similar controversy and backlash.

Fast forward to the twentieth century and consider the case of Robert Johnson, the greatest innovator in the history of the blues—and someone perhaps never before mentioned in the same breath as Saint Benedict—but he too was poisoned, fatally in this case, after living a quasi-mythical life of wandering and testifying that has uncanny similarities to the biography of the founder of the Benedictine Order. There’s even a crossroads story in Benedict’s biography, much like Johnson’s, when in the course of his early life, the future saint had a decisive meeting with a stranger, a hermit he encountered on a path, a holy man named Romanus of Subiaco—who might not have taught him blues guitar, but did steer him toward a life of contemplation and holy chanting. Whether your inspiration is God or the Devil, musical innovation is, it seems, a risky business and takes you on strange journeys.

We can trace this story of musical destruction all the way to the present day, and share accounts of parents and other authority figures literally burning recordings of rock, blues, hip-hop, metal, and other styles of disruptive music—songs possessing an alluring power over hearers almost identical to what Plato warned against back in ancient Greece. In 1979 the demolition of a box of disco records with explosives—as part of a publicity stunt to get fans to attend a Chicago White Sox baseball double-header—turned into a full-fledged riot, with 39 people arrested. Some people will tell you that the age of disco music ended because of that incident. But the destruction didn’t stop there. Just a few years ago, a minor league baseball team attracted a crowd by blowing up Justin Bieber and Miley Cyrus’s music and merchandise in a giant (and aptly-named) boombox. In fact, you could write a whole book about people burning and blowing up music.

But why do we destroy music? In the pages ahead, I will suggest that songs have always played a special role in defining the counterculture and serving as a pathway to experiences outside accepted norms. They are not mere entertainment, as many will have you believe, but exist as an entry point to an alternative universe immune to conventional views and acceptable notions. As such, songs still possess magical power as a gateway on a life-changing quest. And though we may have stopped burning witches at the stake, we still fear their sorcery, and consign to the flames those devilish songs that contain it.

Faced with such threats, which recur in every century, many musicians have learned to rely on coded languages. Robert Graves assures us that Irish bards had to master 150 different cipher alphabets—an education requiring three years of study. If his speculations are correct, these musical performers relied on elaborate codes that incorporated colors, trees, letters of the alphabet, and other details into a rich tapestry of secret meanings. By the way, our persecuted inventor of sheet music Guido of Arezzo, invented a symbol system relying on joints of the fingers very similar to the codes used by the Irish bards. And a few years later, Hildegard von Bingen—arguably the first major European composer known to us by name—developed her own secret language of around one thousand words. Nobody really knows why. Is all that just a string of odd coincidences, or are they part of a larger history of song as a source of secret information too dangerous to share widely?

Yet so many of our most famous composers, from Bach to Shostakovich, have incorporated codes directly into their musical notes. And, as we shall see, these hidden meanings are even more prominent in African-American music. Is all this just a game, a diversion for bored creative people—or something larger? These artists rarely explain their motives, but that in itself is revealing.

It’s curious to note how codes and secret languages have played a prominent role in quest narratives even into the modern day. You find them everywhere, from the cryptic opening of Canto VII of Dante’s Inferno all the way to the strange Dothraki language, complete with a vocabulary of 4,000 words, constructed for George R. R. Martin's fantasy novels and their TV adaptation Game of Thrones. And we will inquire later into the impact of these codes on contemporary music.

But here I want you to focus, just for a moment, on the case of J. R. R. Tolkien—who studied the old bardic tradition more closely than almost any individual of his time and proved, against all odds, its relevance in modern times. His fantasy books The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings launched one of the largest brand franchises in history—a multibillion dollar business that has only grown larger in the decades since the author’s death in 1973. But the whole project started out as a private language, built on Tolkien’s obsession with words, codes, and secret alphabets. His mythology and stories only came later, as an outgrowth of this personal cryptography.

Tolkien’s obsession went so far that he had trouble deciphering his own diary, because of the constantly changing secret alphabet he had constructed. And when he served in the military during World War I, Tolkien turned his back on the prestigious positions of authority he could have achieved, with his Oxford background, and instead trained in the signal corps—where, according to his biographer, “he learnt Morse code, flag and disc signaling, the transmission of messages by heliograph and lamp, the use of signal rockets and field telephones, and even how to handle carrier pigeons (which were sometimes used on the battlefield).” In the midst of the greatest drama of his era, finding himself sent to the front at the start of the Battle of the Somme, Tolkien was focused more on codes than combat. Yet this very mindset, gave us The Lord of the Rings.

As strange as it sounds, we need to view the Derveni papyrus as part of this same tradition. You can even consider it as the founding document in the Western world of the history of the musical hero’s quest as a secret code. But our goal here is not to label it, but actually decipher it.

What we will learn in the process is that this alternative musicology not only helps us understand songs in our own time, but even provides tangible solutions to problems and challenges happening elsewhere in our algorithm-dominated culture.

Put simply, this is a code well worth breaking. . . .

Click here for the rest of chapter one of Music to Raise the Dead: “Why is the Oldest Book in Europe a Work of Music Criticism?” (Part 2 of 2).

In that section we start to decipher the alternative musicology from the Derveni papyrus, and see how radically it rejects the dominant notions about music of our own time.

Footnotes:

The oldest surviving European book: Richard Janko, “Reconstructing (Again) the Opening of the Derveni Papyrus,” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 166, 37-51. The passage quoted is on page 37.

the oldest pharmaceuticals and medical tools: Despina Ignatiadou, “The Warrior Priest in Derveni Grave B Was a Healer Too,” Histoire, Médecine et Santé, Vol. 8 (Winter 2015), pp. 89-113.

Irish bards had to master 150 different cipher alphabets: Robert Graves, The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), p. 292.

he learnt Morse Code: Humphrey Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000), p. 86.

I’m 100% engaged in your work. Thank you. As I read your words, I’m sitting in a recording studio working on a devotional music project which is intended to bring comfort and healing to those who engage the music. Every time I produce this kind of thing certain questions swirl in my mind with which you will perhaps deal. Where is this power to transform resident? Is it in the sound of the music? Is it in those who compose the music? Is it in those who perform the music? Is it in those who receive the music? Is the performance (live or recorded) of this music attended by a spirit (the Holy Spirit in the Christian tradition) which imbues the music with healing properties? Is the power an aggregate of all the above? Yes, I agree, this is a code well worth breaking.

Terrific! Thank you for sharing, thank you for posting this on Substack. So much I didn’t know. Never heard of the Derveni papyrus for instance. I’m haunted by this sentence: “The shape of Western society is the result of a battle of worldviews that took place 2500 years.” I’ve seen a similar version of this argument made about the Renaissance, the rationalists, Descartes, Mersenne, etc, actively suppressing an ancient hermeneutic tradition (Hermes Trisgemistus, etc) that was in the process of being rediscovered. Very interesting to think about this same sort of dynamic at the height of the classical world. Look forward to more!