What Do Conductors Really Do? (Part 1 of 2)

In this section from my new book, I unlock the secret history of the conductor. Even the little stick they hold is much stranger than you think.

Below I’m sharing another installment from my new book Music to Raise the Dead.

Each chapter can be read on its own, as an answer to a specific question (which is always the title of the chapter). So you don’t really need to start this book at the beginning.

But if you do want to check out earlier sections, below is the table of contents—with links to what I’ve already published on Substack.

MUSIC TO RAISE THE DEAD: Table of Contents

Prologue

Introduction The Hero with a Thousand Songs

Why Is the Oldest Book in Europe a Work of Music Criticism? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Is There a Science of Musical Transformation in Human Life? (Part 1) (Part 2)

What Did Robert Johnson Encounter at the Crossroads? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Why Do Heroes Always Have Theme Songs? (Part 1) (Part 2) (Part 3)

What Is Really Inside the Briefcase in Pulp Fiction? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Where Do Music Genres Come From?

Can Music Still Do All This Today?

I’m planning to publish one chapter per month, alongside all the usual stuff at the Honest Broker. I’m hoping to make the book available to all subscribers, but that requires some of you to purchase a paid subscription out of the generosity of your heart to make this possible. (We’re doing soft sell today.)

A paid subscription brings other perks, including access to my 100 Best Albums of 2022—coming at the end of next month—and many other special features.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

What Do Conductors Really Do?

By Ted Gioia

Why do some musicians get called conductors? That’s a little odd, no? A conductor is a person who takes you on a journey—you find them on trains and buses. Their job description is a little vague, but they’re supposed to get us to the destination safely and on time.

But we learned something curious back in chapter one, namely that the oldest book in Europe describes extraordinary musicians exactly like that, powerful singers whose songs keep us safe and guide us on dangerous journeys.

Even stranger, this tradition can be found everywhere in the world. The most famous conductor of this sort was Orpheus, who in the well-known myth actually conducts a dead person back to the realm of the living. But there are hundreds of similar stories from various cultures, and they almost always involve music.

Why do you need a musician to conduct you on a journey to the Underworld or some other ‘next life’ (even if only an alternative universe or mindstate)? Don’t you go to the afterworld, however defined, with a one-way ticket and no traveling companions allowed? Or if you insist on a guide, aren’t you better served by a soldier or theologian—or, best of all, a lawyer to argue your case in that court of final judgment?

But evidence from many cultures makes clear that journeys of this sort inevitably require a conductor, and that musicians possess the essential skills for this role. This is especially true if you plan on making that rarest of all voyages, namely a return trip from the world beyond. You don’t want to get lost on that journey, and without a conductor the risk is enormous.

Before proceeding, it’s worth noting that conductor isn’t the only word with double meanings referring to both music and traveling. Other terms reveal this same convergence—when we refer to the movement of a classical work or a favorite track on a playlist, or even to structural forms such as the fugue (etymologically linked to the verb to flee). Take for example, the ancient Greek word oimê, signifying song, which is connected to the similar word oimos, designating a road or path. Homer makes clear that this is no coincidence, when he praises the bard in the eighth book of the Odyssey, declaring that performers of this sort deserve the utmost honor because the Muse has taught them the “song-path.” Here all three ingredients are brought together: the music, the path, and the conductor.

Fast forward to the present day, when Aboriginal communities in Australia celebrate the Songlines, which are literally travel itineraries in the form of music. As in Homer, this is a genuine song-path, but Aboriginal belief systems didn’t get this notion from the Odyssey or Orpheus. In fact, these songs literally spring from the landscape—or, to be more accurate, the terrain arises from the songs.

What a peculiar convergence of meanings. But this is just the start.

The Muse—whose very name is etymologically linked to music—is an especially powerful conductor, literally a goddess, and the special guide of poets, bards, and other creative individuals. She is invoked by Homer at the start of the Iliad and Odyssey. Virgil calls on her in the opening of the Aeneid and Ovid does the same in the Metamorphoses. Milton turns to her at the beginning of Paradise Lost, despite the apparent contradiction of invoking the pagan Muse at the outset of a Christian epic.

Robert Graves was still honoring her—and insisting on the Muse’s continuing relevance as the source of all great poetry—in the midst of the 20th century modernist movements. “I cannot think of any true poet from Homer onwards who has not independently recorded his experience of her,” he proclaims in The White Goddess—“a true poem,” in his view, “is an invocation.” Here and in so many other similar contexts, the Muse is courted as the source of inspiration whenever an artist is planning to undertake an extraordinary, life-changing project—anything of truly epic proportions.

As these examples indicate, a conductor is required for momentous undertakings even if no physical journey is involved. This will become very important to us in the pages ahead, where we will need to recalibrate all our notions of the hero’s quest and how it is pursued. At this juncture it suffices to point out that the creative act itself is sufficiently perilous and uncertain on its own, and requires guidance, preferably (according to this tradition) from a woman with special powers and identified by name with music.

Current-day conductors are admittedly poor substitutes for goddesses, although many make quite an effort to cultivate a larger-than-life personality, as any experienced orchestra player will tell you. But the role itself seems to transform these stick-shakers into quasi-deities, at least in the minds of audiences, no matter how severe their personal failings.

Even more surprising, the same double meanings reside in the conductor’s baton, a tool so simple and banal that it’s often mocked. I’ve heard many ask whether that tiny stick really achieves anything. Isn’t waving a hand just as good? Maybe even the whole idea of a conductor is worthless. Can’t the musicians manage on their own?

I’m reminded of Fellini’s amusing film Orchestra Rehearsal, where musicians mount a revolt, replacing their dictatorial conductor with a ten-foot-tall metronome. It’s not quite as absurd as it sounds. Even a sophisticated symphony fan may wonder what the person with the baton really adds, especially when they see that most of the musicians are looking at the score and seemingly ignoring their demonstrative, wand-waving boss.

But the history here is revealing.

The ancient rhapsode (or epic singer) carried a laurel staff or wand as a sign of authority. This was no ordinary piece of wood. Hesiod, one of the earliest singing poets in recorded history—he lived almost three hundred years before Socrates and the rise of philosophy—claims that the Muses actually came to him while he was shepherding and handed him the laurel staff as a symbol of his divine authority. This decisive interaction with these goddesses empowered his singing of tales.

In other words, a magic wand was the predecessor of today’s conductor’s baton.

For as far back as we can trace, accounts of the afterlife have emphasized these musical connections, not just for the conductors of the journey but for all participants. Even today, the pursuit most commonly associated with the departed in the next world is playing music—usually on a harp. God’s closest allies, the angels, are seen both as forces of intercession with the ultimate divine power, and also as kickass musicians.

And somehow, when we show up in that higher realm, we get our own harp. If I can judge by general consensus (and popular culture), it is the only absolutely required tool for getting by in the Good Place.

But that’s just Christianity, and musical connections show up in every other belief system that envisions a plane of existence beyond our own. The ancient Greeks associated choral dancing with the afterlife, as documented by countless funerary inscriptions. In the Zoroastrian tradition, the souls of the departed cross Chinvat Bridge, where the worthy are escorted by Daena, a female guide representing divine revelation, to the aptly-named House of Song. The texts of songs about the afterlife found on Egyptian tombs, going back to the Middle Kingdom, are accompanied by images of blind harpers, who seem to possess some inherent authority for their pronouncements—hence these hymns are known nowadays as “Harper’s Songs”

Why the harp? In Christian tradition, the harp has been associated with heaven at least as far back as the Book of Revelation (14:2), where the sound of paradise is explicitly compared to the music of an ensemble of harpists. But, as the Egyptian images suggest, there is a much older tradition linking stringed instruments with the afterlife. Ancient sources tell us that Orpheus drew on Egypt for much of his expertise, so we shouldn’t be surprised to find that he is frequently depicted holding a lyre, similar in appearance to a small harp, on countless ancient works of art. With the rise of Greek philosophy and a more rationalistic outlook, this notion lost none of its charm—in fact, it was extremely pleasing to the leading thinkers, who considered the well-tuned lyre as an emblem of a well-tuned universe.

An ancient reference to a lost work attributed to Orpheus called Lyra even goes so far as to insist that “souls cannot ascend without a lyre.” Some of the most respected authorities in the classical world offered similar verdicts. We are told that Pythagoras asked his followers to play the lyre at the time of his death, obviously to ensure a propitious soundtrack for his final journey. In ancient Rome, Cicero expressed a similar confidence in the lyre, declaring that “learned men, by imitating this harmony on stringed instruments and song have opened for themselves their return to this place [the heavenly spheres].”

Get a harp and go to heaven? Is it really that simple?

But there’s an alternative view, mostly forgotten and marginalized, that links heroic quests and the afterlife with drums, not string instruments. These magical drums are powerful tools with a history that predates even the Egyptian Harper’s Songs. Around the same time that Greek road workers found the Derveni papyrus, archeologists in Turkey uncovered an almost 8,000-year-old shrine wall with images from the ancient city of Çatal Hüyük depicting musicians dressed in animal skins playing percussion instruments. Other ancient images and figurines from a wide range of locales—spanning Asia, Africa, and Europe—show similar performances, most often by women playing frame drums.

In fact, the earliest drummer known to us by name is one of these women, Lipushiau, who was priestess of Ur (circa 2380 BC). As in our discussion of the Muse above, women seemed to possess a special relationship with creative forces in these early societies, although here communal aims of fertility and propagation were probably more important than any purely aesthetic conceptions of creativity.

This image of paradise-with-a-beat also has Biblical validation. In Ezekiel 28:13, for example, we learn that the tambourine was played in Eden. You can still see tambourines today in the hands of the angels of Signorelli’s painting of heaven at the Cathedral in Orvieto, Titian’s Assumption of the Virgin in Venice, and in various works by Fra Angelico and his followers.

You may think that arguments over which instruments are played in heaven is pointless. Who cares whether angels prefer harps or drums? But this seemingly small detail is quite significant. The drum is the instrument of rhythm and forward momentum, and has always been associated with movement, journeys, and trance states. In 1962, scientist Andrew Neher shook up many music scholars with his paper on drumming and brainwaves as a defining factor in human societies—a scholarly study entitled “A Physiological Explanation of Unusual Behavior in Ceremonies Involving Drums.” This work followed on Neher’s earlier experiments showing that a snare drum beat could actually change the electroencephalogram pattern for test subjects. But this merely gave scientific validation to what our Bronze Age ancestors already knew, namely that drums provide a pathway to another place, an altered mind state where unexpected things can happen.

Societies that envision a heaven where string instruments are played have different priorities. The string instrument is, for them, less a tool of transcendence and ecstasy, and more a metaphor for a well-tuned, harmonious existence. Harmony, in these settings, is associated with orderliness and stability, not journeys and altered mind states. The leaders of societies that celebrate metaphors of harmony often fear and repress the “unusual behavior” described by Neher, and prefer religious and political institutions that instill rationality and conformity. This is why we shouldn’t be surprised (as are many scholars) that those famous Harper’s Songs from the Egyptian Middle Kingdom sometimes express skepticism about the afterlife. The best known of these songs, found in the tomb of Intef, actually states that we don’t really know what happens after we die, so we are wise to keep our expectations in check.

When you trace out these changes on a larger timeline—especially drawing in the shamanic implications discussed later in this book—the implication is clear. The drum, when used in rituals, aims to transform and enliven the participants in a manner resembling intoxication; the harp and lyre serve to subdue and rationalize. One takes you on a trip; the other keeps you in your place.

We are now beginning to understand why you need the right musician as your conductor on a vision quest. The rhythm of the music creates the road for this journey. And does a lot more, too—as we shall see in the pages ahead.

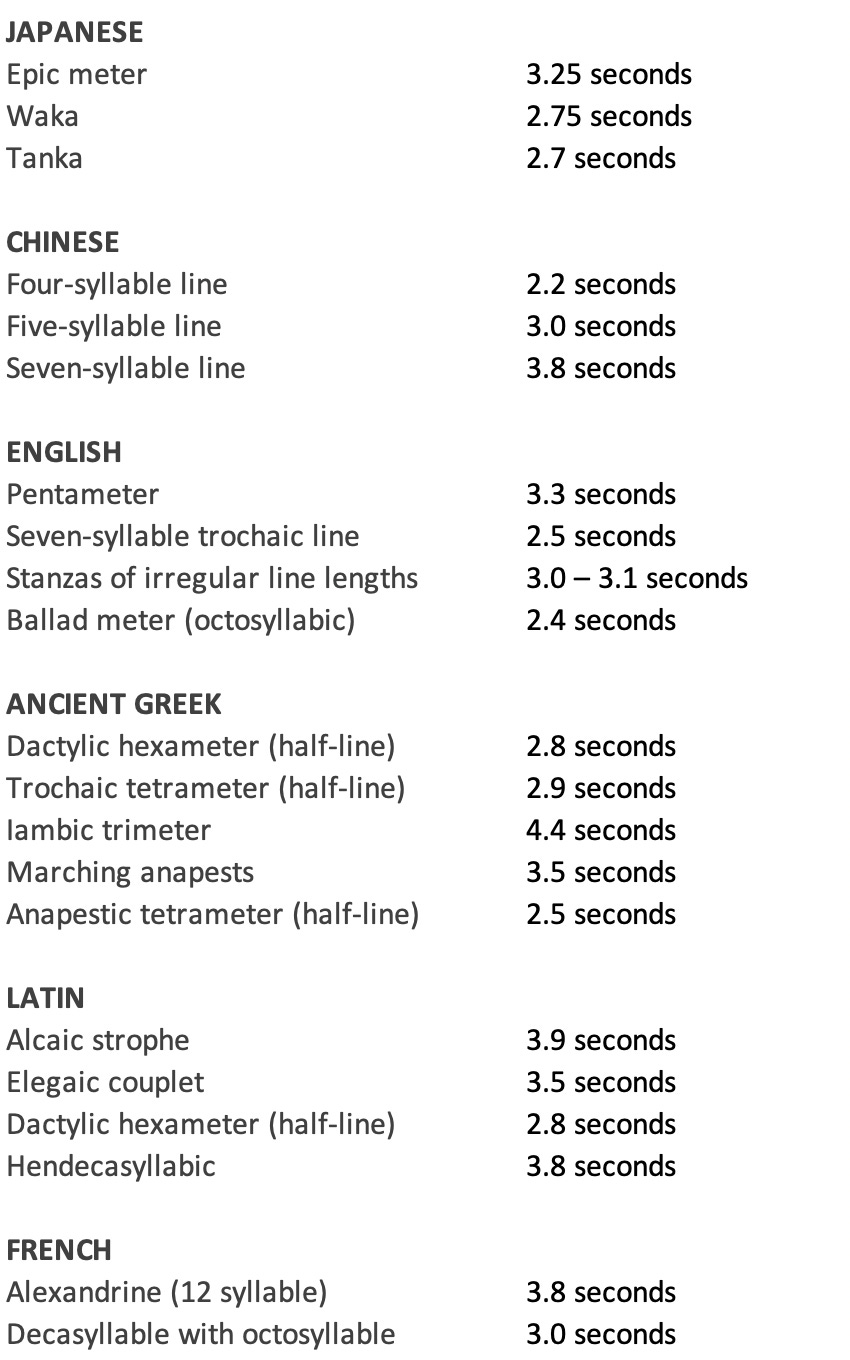

Even after epics and lyrics lost their music, evolving into purely literary endeavors, these rhythms remained in the meter of the poetry. Poet Frederick Turner and psychophysicist Ernst Pöppel have even quantified this elusive and almost magical propulsive force. When they studied traditional poetry of 18 different cultures, they discovered an extraordinary convergence of rhythmic structure. Even as the subject matter and meter differed, the elapsed time to recite a line hardly varied. These researchers concluded that “all human poetry possesses regular lines that take roughly three seconds to recite.”

Here are their measurements for the poetry traditions they investigated most closely:

In addition, Pöppel conducted an analysis of 200 German poems, of various line lengths, and determined that 73% of them lasted two or three seconds. In a very real sense, this is the pace of the journey or quest.

Nowadays we consider meter as a boring topic that only concerns poets and literary critics. But, as with song, meter in its earliest manifestations is closely linked with sorcery and divination. I note that the hexameter used by Homer to invoke the Muse is the same meter associated with the hymns of Orpheus and the oracles given at Delphi. How peculiar that soothsaying and predictions about the future always had to be constructed in this same poetic meter—the identical beat that serves as a guide in a journey to the Underworld! But that should tell us that these structural devices originated with more than mere aesthetics in mind.

Critics refer to this meter as a formal constraint, but it’s better described as the pace of the trip. And its force derives not from culture, but from the structure of the human brain. A large body of research now makes clear how external rhythms influence biological rhythms, and can induce a pleasing trance state. But more than just pleasure is involved here. The brain is better skilled at processing and remembering information when it is packaged in musical rhythms. That is why bards, griots, and other singers have served as custodians for the histories and practical knowledge of their communities—it’s no exaggeration to call them the cloud storage of traditional society. They can serve this function only because their songs and poems are well-designed technologies for preserving wisdom and knowledge.

We have all experienced this first hand. When I was first learning the alphabet, my teachers taught me the ABC song, wisely deciding that I would remember this lesson if it came with a rhythm and melody. Other musical lessons followed, at both home and school, and the fact that I can remember so many of these melodies today, decades after I stopped singing them, testifies to the long-term storage capacity of this kind of musical learning.

You can find many versions of the “Alphabet Song” on YouTube, some with a billion or more views. Many people are skeptical when I say that music is mind-expanding, but examples of this sort make the point far more eloquently than anything I can say.

These structures are more pervasive and enduring than we realize. The oldest evidence from English, for example, makes clear that the first bards sang with four stressed beats per line, and this primal rhythm has persisted in the language through every change of fashion and genre over the centuries. That’s why you find it in alphabet songs, nursery rhymes, dances, popular poetry (such as Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha” or Blake’s “The Tyger”), the US national anthem, and most notably the 4/4 commercial music of modern times.

In other words, there’s a direct connecting thread from Beowulf to Beyoncė and beyond. And though I can’t predict the music trends of fifty or one hundred years from now, it’s a safe bet that those four beats will keep on pulsating long into the future.

Because these rhythms are matched to the needs of the human organism, they persist even when no sound is present. Turner describes his discussion with an expert on mime, who confirmed that three-second phrases also predominate in that purely visual medium. I note that the average shot lengths in Hollywood blockbuster movies are typically in the same range. In the Transformers movies, the time between camera angle cuts are typically between 3 and 3.4 seconds. The film Inception had an average shot length of 3.1 seconds. Spiderman clocks in at an average shot length of 3.6 seconds. Even Hollywood understands, or so it seems, that this is the pace at which heroes operate. But the same is true, of course, in successful music videos. Or hand gestures in a presentation. Or movement phrases in a dance.

It’s hard to escape the conclusion: rhythm, the foundation of music, augments the information content of any message—provided it moves ahead at the correct pace. When embedded in the beat, the content is amplified the same way a cell phone call is strengthened by a signal booster. A weak message becomes a strong one through the musical rhythm, the catchiness of what today we would call its groove.

Once we understand this, our whole notion of the origin of the hero’s journey, and its literary expression, starts to change. We tend nowadays to consider Homer and other ancient bards as storytellers, but in fact they might have been much more like rappers, DJs, and others who work off the beat….

Click here for the second part of “What Do Conductors Really Do?”

A true poem: Robert Graves, The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), p. 20.

souls cannot ascend without a lyre: Alberto Bernabé, “Orphics and Pythagoreans: The Greek Perspective,” from On Pythagoreanism, edited by Gabrielle Cornelli, Richard McKirahan, and Constantinos Macris (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2013), p. 124.

Cicero expressed a similar: Cicero, On the Commonwealth and On the Laws, edited by James E.G. Zetzel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. 99.

all human poetry possesses: Frederick Turner, Natural Classicism (New York: Paragon, 1985), p. 12.

this is the pace of the quest: Frederick Turner, Natural Classicism (New York: Paragon, 1985), pp. 75-76.

As a teacher of singing, I note that the range typically given for a normal respiration rate is 12-20 breaths per minute. Here's a physiological origin for the 3-second phrase length!

You make some really great points about rhythm. Even Genghis Kahn used rhyme schemes for his commanders to issue orders to his troops. They found that giving orders in rhyme greatly reduced confusion and problems due to miscommunication.