The Real Story of Blues Legend Robert Johnson's 'Deal with the Devil' at the Crossroads

In this section from my new book, I uncover neglected source materials from the 1930s and provide new insights into the most famous story in blues history

Below is a section from my new book, Music to Raise the Dead, which I’m publishing in installments on Substack. This chapter shares the results of many years of research into the most famous story in the history of the blues—namely guitarist Robert Johnson’s legendary deal with the Devil.

I promise to provide insights here you won’t find anywhere else. My approach allows us to solve mysteries about the blues and American music that have long bedeviled (an appropriate word in this instance) experts, and also uncover hidden elements in our current-day music culture.

Each installment of my book can be read as a stand-alone essay, or as part of the larger narrative. Below is a table of contents for the entire work—with links to the sections already published.

MUSIC TO RAISE THE DEAD: Table of Contents

Prologue

Introduction The Hero with a Thousand Songs

Why Is the Oldest Book in Europe a Work of Music Criticism? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Is There a Science of Musical Transformation in Human Life? (Part 1) (Part 2)

What Did Robert Johnson Encounter at the Crossroads? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Why Do Heroes Always Have Theme Songs? (Part 1) (Part 2) (Part 3)

What Is Really Inside the Briefcase in Pulp Fiction? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Where Do Music Genres Come From?

Can Music Still Do All This Today?

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

What Did Robert Johnson Encounter at the Crossroads? (Part 2 of 2)

By Ted Gioia

The crossroads shows up in three separate places in Plato’s accounts of the afterlife. In the Gorgias, Plato describes a “Meadow at the Crossroads,” where one path goes to the Isles of the Blessed, while the other leads to a prison of punishment and retribution.

The imagery recurs in the Republic, where we are told that the virtuous person departs to the right and ascends to the heavens, while the rest must travel to the left and downwards, where they pay a “tenfold penalty for each injustice.” Socrates assures us that this isn’t just idle speculation. His source is a soldier who was killed in battle, and twelve days later was placed on the funeral pyre—where he revived, to the shock of onlookers, and gave his account of what he had seen and heard in the world beyond.

But the most interesting Platonic reference to the crossroads comes in the Phaedo, where the philosopher offers an important clarification. He explains that this dangerous trip isn’t made alone, but that the dead “proceed to the underworld with the guide who has been appointed to lead them thither from here.” Plato adds that this guide is essential because the path “is neither one nor simple, for then there would be no need of guides; one could not make any mistake if there were but one path. As it is, it is likely to have many forks and crossroads.”

Once you are aware of the larger significance of forks and crossroads in these settings, you start noticing them everywhere. They show up in the Faust legend, and in Transylvanian folklore, and even that often-quoted poem about two roads by Robert Frost. Xenophon's Memorabilia tells the story of Hercules at the crossroads, where the intersecting roads represents a defining decision between a life of honor or one of disgrace—a story that was even set to music by Bach and Handel. And we can find similar accounts in so many other cultural settings, from The Pilgrim’s Progress to pagan rituals honoring the Norse god Odin. I suspect that you could put together an entire essay just documenting the use of crossroads in video games.

As we have already seen, the conductor on these journeys is often a musician. But even with the best preparation, the mission sometimes fails—and this is a significant difference between the vision quest and the Hollywood hero’s journey, which requires a happy ending. The first documented Orpheus-type myth in the New World, recorded in 1636 by Father Jean de Brébeuf as told by a Huron shaman, recounts a trip to the Village of the Dead, after fasting and a vigil, to reclaim the soul of the man’s dead sister. He did everything according to plan, singing his songs of power and calling upon spirit helpers, but still failed in his mission.

A complete inquiry into these myths, now widely documented in so many settings, reveals that such failures are common. Those who embark on these dangerous trips, where dark powers are confronted, do so at great risk.

I doubt that Robert Johnson knew about Plato’s accounts of the crossroads, and he certainly had no familiarity with the Derveni Papyrus, still buried in the ground during his lifetime. It’s more possible that he had heard the Orphic myths of Native American culture. But we hardly need to make such a leap, because a rich body of African and African-American lore of his day was obsessively concerned with what happened at the crossroads.

Once again, we have no need to consult 1960s blues fans to learn about this, and in fact will only be misled if we turn to them for guidance. The blues revisionists would be better served by studying traditional African “dilemma tales”—which have been documented in at least 84 different ethnic groups from all over the continent—a rich body of work that has extraordinary implications for anyone hoping to understand the meaning of the blues. It’s a shame that American music scholars pay so little attention to such matters.

William Bascom, who collected 449 of these stories, lamented that these narratives are even ignored by folklorists, who dismiss them as having “little literary merit.” These stories always involve protagonists facing a choice of critical importance, sometimes taking place at a crossroads, and mix elements of superstition with aspect of utmost realism. They are often used for didactic purposes, or told as a kind of riddle, but—like the quest narrative in other cultures (and in striking contrast to the Hollywood version)—they aspire to something more than mere entertainment and diversion. The listener is expected to grapple with the life-changing questions at stake in the dilemma, much as we have already seen in the crossroads traditions from other cultures.

But the connection between African-American folklore and Robert Johnson is even more marked in the figure of the supernatural conductor who presides over the crossroads. In Brazil, practitioners of Candomblé, a syncretic religion combining aspects of Yoruban belief systems from West Africa and Roman Catholicism, pay homage to the trickster deity Exu (or Eshu), who controls roads and doorways. The risks of encountering him on your pathway can perhaps be gauged from the fact that his name was long mistranslated into English as Satan or the Devil—technically inaccurate, but perhaps emotionally significant.

When I was doing research in Brazil, I learned that offerings to Exu are often seen at crossroads even in the current day. In Haiti and parts of the United States we find a similar figure named Papa Legba, who is depicted wearing a straw hat and smoking a pipe. He is linked with dogs (call them hellhounds, if you like). In Cuba we hear of a similar trickster known as Eleguá, whose colors are red and black. Here too some have identified this figure as the Devil; and though many believers in Santería, the African-influenced Cuban folk religion, disagree, even they acknowledge that Eleguá is a dangerous character who must be approached with caution.

But is any of this relevant to our inquiry into Robert Johnson and the origins of the blues? Would African Americans who came of age in Mississippi during the 1920s and 1930s have known about these folkloric figures and belief systems? We are fortunate that a determined amateur ethnographer named Harry Middleton Hyatt tried to answer that very question, and devoted much of his life to this project.

In the 1920s Hyatt grew convinced that witchcraft was still actively practiced in the modern day, especially in the American South. To prove this, he amassed “the best and largest folklore collection ever assembled in the United States.” But, much to his disappointment, Hyatt learned that academics and published works couldn’t answer his questions, which required intensive interviewing and fieldwork.

He undertook the responsibility for doing just that, and with relentless energy—although, as his biographer notes, “much of what his informants were telling him seemed too incredible to accept.” This research, I note, took place during the exact same period when Robert Johnson was performing and recording his music, and in many of the same communities. By the time Hyatt was finished with this massive project, his findings took up almost five thousand pages with material drawn from 1,606 informants and documented on three thousand cylinder recordings.

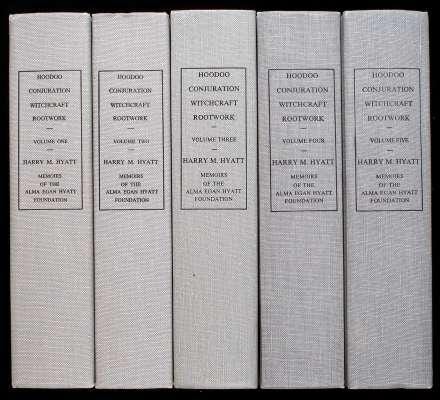

This was far more than any commercial publisher could envision issuing, but Hyatt eventually shared his research in five thick self-published volumes entitled Hoodoo-Conjuration-Witchcraft-Rootwork—a compendium of material that testified to the widespread survival of African belief systems in the very same places that gave birth to the blues. It’s unfortunate that the revisionists who have tried to rewrite the story of Robert Johnson have not learned from this remarkable work—because it would have overturned many of their most tendentious theories.

The simple truth is that this massive oral history from the 1930s tells us exactly what we need to learn to grasp the real meaning of the crossroads in Johnson’s life and music. As we shall see, it even provides clues to deciphering mysterious lyrics that others have failed to understand.

“The most common reason people made a deal with the Devil, according to these accounts, was the desire to play a musical instrument.”

“I did not begin with preconceived theories,” Hyatt explains at the conclusion of his project. “Rather, I let my informants tell me what they knew, believed and practiced.” If interview subjects asked what he was doing, Hyatt simply replied that he was studying hoodoo, and let the informants take the discussion in whatever direction they wanted. He ran into many obstacles along the way, many of them only incidentally related to his research.

In Memphis, Hyatt was raided by the police, and essentially run out of town. In New Orleans, a journalist investigated him as a potential drug dealer. In other communities, Hyatt got branded as everything from a government agent to a kingpin of organized crime. In many locales, stool pigeons posed as informants, but were merely gathering information for authorities who were concerned about this suspicious visitor to the their community.

Hyatt eventually published, as an appendix to his research, a collection of signed letters of permission from local police authorities, authorizing his activities in “colored neighborhoods.” Hyatt had learned through hard experience that operating without these endorsements was a risky proposition. But even simple logistical problems were a constant hassle.

Hyatt lost a huge amount of material because his recording equipment failed—perhaps enough information to fill another book. He later lamented that his life would have been far easier if only the cassette tape had been invented 35 years earlier. But a lack of informants and their stories was never an obstacle. Back in the 1930s, the sheer mass of available firsthand information on these magical and supernatural practices was nothing short of astounding.

Sad to say, Hyatt’s work is little known and seldom consulted nowadays. Only a few hundred copies of Hoodoo-Conjuration-Witchcraft-Rootwork were ever printed, and these are almost impossible to find—I recently saw one set put on the market with an asking price of $8,500. The few surviving copies are hoarded, I suspect, by actual practicing sorcerers—whose numbers have probably increased since the Harry Potter brand franchise took off. As a result, few specialized folklorists have ever seen a copy—let alone owned one—and even fewer music researchers.

Many years elapsed between the time I first learned of Hyatt’s research, and actually got access to it. But its value to a blues scholar is inestimable, maybe even more than the hefty asking price. In these pages—which ostensibly have nothing to do with music in general or blues in particular—we find the full range of imagery and attitudes that came to the forefront in the songs performed by Robert Johnson and so many other blues innovators.

Sorcerers in New Orleans and Memphis, for example, told Hyatt that witchcraft was so common in their communities that you could buy magic powder or the lucky bone from a black cat at many local drugstores. The befuddled Hyatt asked in disbelief: “Would they sell it to me?” The answer: “Everything you want.”

That’s the milieu in which Robert Johnson came of age—a society where you purchased magical potions at drugstores on Main Street.

But for our purposes, the most important information here involves deals with the Devil—and Hyatt shares dozens of examples. These come both from people who knew about such transactions, as well as from those who had actually made them. And most of these deals, he tells us, took place either at a crossroads or a fork in the road (although, in a few cases, a cemetery or church yard or other spiritually-charged setting could suffice).

Can you guess what the number one reason people gave Hyatt as the purpose for making these deals with the Devil? A range of goals are documented in Hyatt’s indefatigable field work—testimonies of people who wanted to win at dice, or have a streak of good luck in their everyday life, or even learn how to dance. But the most common reason people made a deal with the Devil, according to these accounts, was the desire to play a musical instrument.

And the most popular instrument for this devilish instruction was the guitar, with the banjo a close second. A few scattered accounts mention violin or harmonica, but curiously enough Satan doesn’t seem to have much interest in pianos or saxophones or trumpets. If you didn’t know it already, you would walk away from these oral histories with the sure knowledge that the guitar is the Devil’s favorite instrument.

“At exactly twelve o’clock on Friday night, you go to a crossroads, any crossroads,” one informant told Hyatt, “and there you are to kneel and say you make vow to stay wit the devil, and do whatever he wants yo’ to do—hell, raise destruction—what not—from now until long as yo’ live—and that’s the vow to de devil.”

But there is a loophole—a way to extricate yourself from this ominous contract. “And to overcome this and to change, why you have to go right back to the same crossroads and make a vow to reform.” The informant adds that the person needs to “face to the east” while breaking this contract.

Let me share another account of a deal with the Devil at the crossroads collected by Hyatt—and this time we have something quite extraordinary. He interviewed a man who had actually done this, and then later broke his contract with Satan:

“The reason I tell you that is because I tried it one time when I wanted to learn to play music on de guitar, an' pretty soon I found out that it was true—why, I throwed de guitar right down an' I walked off an' left 'im. So that break the tie [the compact between him and the Devil].”

This informant also emphasized the importance of facing in the right direction. You stand at “the cross roads an' you turn your face to the west, your back to the east, your right to the north an' your left to the south, an' you shall call this man who pretend to do anything that you desires.” Even more fascinating, he provides a comforting detail that a contract with the Devil is not in perpetuity, but has an expiration date. You have only “sold your soul outright for seven years.”

It’s amazing that blues researchers have written books about the crossroads mythos without learning from these remarkable testimonies. But if you don’t, you can’t even begin to grasp Robert Johnson’s life story and music.

Just consider the opening to Robert Johnson’s “Cross Road Blues”—which he recorded approximately seven years after his alleged midnight encounter.

I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees

I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees

Asked the Lord above, “Have mercy now,

Save poor Bob if you please…”

And a few measures later in the song, we find:

And I went to the crossroad, mama, I looked east and west…

Not only is it hard to apply a secular interpretation to this song, it’s simply impossible. And the knowledgeable listener who has studied the prevalent beliefs of Robert Johnson’s time and place concludes not only that the musician had an intense crossroads experience, but that he might have made a second visit to the site to renege on whatever contract, real or imaginary, that resulted from his first visit. Certainly the invocation to “the Lord above” in “Cross Road Blues” supports such an interpretation. Perhaps Johnson felt that his term of servitude had expired, and he could make a fresh start.

Much speculation has surrounded the incidents leading up to Robert Johnson’s death in 1938 at age 27, most likely due to poisoning from a man jealous of the musician’s attentions to his wife. But Johnson’s family took particular note of a piece of paper that came into their possession as part of the guitarist’s final effects. They called it his testimony, and it was written in green ink in Johnson’s own hand.

The text was just one sentence: “Jesus of Nazareth, king of Jerusalem, I know my Redeemer liveth and that He Will call me from the Grave.” You can assign any number of interpretations to that simple statement. But what you can’t do is use it as evidence of a secularized or agnostic worldview.

Put simply, the accumulated evidence of Johnson’s life and the culture of the communities where he lived matches closely with the words in his songs. The picture they present is anything but the modernized and demythologized entertainer that revisionists have struggled to substitute for the anguished singer of dark and troubled blues.

In fact, a more persuasive account would embrace the clear metaphysical overtones of Robert Johnson’s worldview. We might even consider the possibility that he reclaimed a soul from some realm beyond everyday experience, much like Orpheus or the visionaries in the Native American Orphic tradition. But with an intriguing twist: the soul at risk was his own. At least that’s how he seemed to view matters.

I know that many readers, especially those with a rationalistic or anti-metaphysical mindset, will find this troubling. Not only don’t people make deals with the Devil but—they will insist—there isn’t even a possibility of making a deal with Devil. Such a contract can be no more binding than a letter to Santa Claus or a promise to the tooth fairy. According to this mindset, built on empiricism and a scientific outlook, any reasonable person must reject the crossroads myth as total balderdash, unworthy of serious consideration.

I have some good news for these skeptics. They can accept the crossroads story without abandoning their rationalistic mindset and while maintaining the strictest allegiance to science. And they may need to do just that because, given the preponderance of evidence, the crossroads myth isn’t going away. The Devil is so deeply embedded in Robert Johnson’s lyrics, his life and times, his legacy, and the surrounding culture permeating his music, that any attempt to impose a purified, hard-headed account of this artist that eliminates this part of the story is doomed to failure from the outset. You can’t sweep the crossroads narrative under the carpet or blame 1960s blues fans for attaching it to Johnson’s oeuvre. It’s woven into the inner workings of Robert Johnson and his music.

We have a range of options here that don’t require the Devil to make an actual appearance at midnight down on Highway 61. It’s possible, for example, that Robert Johnson went to the crossroads and pledged his soul in some ritualistic way that fell short of an encounter with an otherworldly force. It’s also possible that he never went to the crossroads, but viewed certain life events—his decision to learn the blues, for example, or the death of his wife in childbirth while he was on the road playing guitar—as representing a symbolic crossroads moment, a renunciation of the virtuous path taken by the righteous.

We can be certain that others in the community viewed his behavior in precisely those terms. Many, perhaps most, of his contemporaries in Mississippi would have judged Robert Johnson as being in league with the Devil merely by observing his lifestyle. It’s worth noting that Johnson’s family included a preacher who talked about the crossroads in sermons, drawing on Jeremiah 6:16: “Stand at the crossroads and look; ask for the ancient paths, ask where the good way is, and walk in it, and you will find rest for your souls.” For these people of faith in 1930s Mississippi, a crossroads decision wasn’t ignorance or superstition, but solid theology. And it didn’t require an actual intersection or fork in the road to be binding.

Finally, Johnson may simply have embraced the dark, devilish connections of his music as a good marketing device, much as rockers did in a later generation. The very religiosity of those around him ensured that the crossroads story would capture their attention. Under this last scenario, Johnson himself might have been a hard-headed empiricist who scoffed at the superstitious views of his contemporaries, but knew how to manipulate their ignorance.

Even the most skeptical reader should have no trouble accepting at least one of these interpretations of the crossroads story. But the last explanation, although technically possible, must be viewed as the least likely of them all. Johnson’s final “testimony” in his own handwriting, carefully preserved word-for-word by his family, shows that he took matters of redemption very seriously. And the songs themselves don’t sound like marketing gimmicks. If you don’t hear a haunted man in these performances, you will have a difficult time explaining why this music has had such a profound impact on listeners. In my opinion, you won’t be able to explain it at all—for the simple reason that this is some of the least gimmicky music in the long history of American song. These recordings have inspired awe and trembling for almost a century, and for a good reason. They feel real, desperately real, and any interpretation of the music that doesn’t grapple with that almost instinctive reaction from listeners is hardly a legitimate explanation.

And even in another hundred years this won’t change, not in the slightest. I’ve lived with this music for decades, and it doesn’t sound any less haunted and haunting with the passage of time. If anything, the opposite is true. For better or worse, we are left with Robert Johnson facing his personal crossroads, an intersection as enduring as any you will find on an actual roadway. We can’t understand one without the other.

Before concluding this chapter, it’s essential to place all this in the larger context of historic and mythic vision quests—which will show us that Robert Johnson was no outlier or exception, but part of a powerful, larger tradition that demands our attention and respect. When viewed in this broader context, it becomes even harder to dismiss his crossroads encounter as hokum or a gimmick. Such a view doesn’t only misrepresent this particular blues singer, but fails to take cognizance of an entire tradition.

I mentioned at the outset of this book that the Native American vision quest should serve as a role model and ideal type in understanding these kinds of encounters. We will learn more about this in the pages ahead, but even at this juncture it’s essential to consider what we have just learned about Robert Johnson in light of this tradition. The connections, as you will see are extraordinary.

The Native American vision quest is now documented in a shelf-full of books, many of them strange and unsatisfying. The first accounts, mostly from missionaries, treated the rituals and resulting visions as mostly a matter of ignorance and superstition (much as some critics today deal with the crossroads story), and a later wave of scholarly studies—for example, Jackson Steward Lincoln’s The Dream in Primitive Culture or George Devereux’s Reality and Dream: Psychotherapy of a Plains Indian—proved to be, if anything, even more reductionist in their insistence on portraying the quest in terms of clumsy Freudian stick figures.

Even some first-person accounts from actual vision quest participants have been cleansed and filtered for mass consumption. For our purposes here, I will quote from Lee Irwin’s more reliable survey The Dream Seekers: Native American Visionary Traditions of the Great Plains, a work that made great strides towards dealing with these practices on their own terms.

Here are the key elements of the vision quest, drawn from Irwin’s survey of eighty different tribal societies—as quoted directly from his text:

“The intentional center of the visionary encounter is the set of instructions, songs, and gifts given to the visionary.” [p. 143.]

“Contact with the sacred powers is widely regarded as dangerous….The increased intensity and the arising of the uncanny aspects of the vision experience, coupled with isolation and exposure, drives many to abandon the quest.” [p. 123.]

“According to the ethnography, the most fundamental condition for the visionary, power-bestowing dream is that of isolation.” [p. 83.]

“The axis of the visionary encounter turns on the singing and the songs given…and points to the central significant of the song as instructive medium of power.” [p. 148.]

“The mark of empowerment is the ability to accomplish anything beyond the ordinary, including continual success in everyday tasks.” [p. 151.]

“Powers could be used to enhance and promote human welfare or to destroy and seduce.” [p. 152.]

“Its inherent potency, taking on the specific aspects of individual experience, is then shared with others through unusual and often remarkable demonstrations.” [p. 119]

“Talk about power is empty. The verbal aspect resides in the song.” [p. 208.]

In sum, a person faces a decisive encounter at a milestone moment of transition in life. It takes place at an isolated locale, and involves a fearful engagement with a dangerous external party. Here, an exchange is made, focusing on powerful songs.

The successful visionary leaves the encounter transformed, and possessing music of tremendous potency. The empowered individual returns to everyday life marked by the experience and able to demonstrate a newfound mastery. Yet the individual now faces risks and dangers related to this transfer of power.

I don’t think I even need to point out how much this overlaps with what we’ve learned about Robert Johnson. In other words, the vision quest not only survived into modern times, but entered into the mainstream of commercial music—where it still resides today. After all, even the most abbreviated chart of Johnson’s influence shows its lasting impact everywhere.

The story of the vision quest is also the story of the blues—and via the blues it enters into rock, pop, folk, and other genres. As we shall see in the pages ahead, this simple fact possesses tremendous explanatory power. It’s an invaluable guide for any scholar involved in the study of music and social history, as well as for those who merely want to tap into the deeper capacities of the songs they hear in their day-to-day lives.

Yet this is a very different way of conceptualizing song than we find in musicology or other conventional approaches to music. The mythos resists reduction to written or codified form. That which is uncanny begins at precisely the point where codification loses power.

These descriptors of the vision quest serve as a suitable summary of this chapter. They show, first and foremost, that the crossroads story is hardly a modern invention or even less a shallow marketing gimmick, but links back to the oldest musical tradition in the world. This is why it inspires such awe and cannot be cleansed from the record, despite persistent efforts to reimagine music history without it.

This also prepares us for the next stage of our study, where we try to find out whether songs can really fulfill these extraordinary promises and expectations. If music can propel a heroic quest, this seems to place musicology in a very different position from the one it holds today—perhaps even implying formidable powers or a hard-earned wisdom that continues to influence people long after the music has stopped playing. Songs, from this point of view, are anything but entertainment or escapism, but truly world-changing and life-changing.

And if, against all odds and contrary to conventional expectations, songs actually possessed this larger capability in the past, this raises the unavoidable and vital question: Can they still possess it today?

CLICK HERE for Chapter 5 of Music to Raise the Dead: “Where Did Musicology Come From?”

Footnotes:

the most interesting Platonic reference to the crossroads: Plato, Gorgias, 524a–524b, translated by W.C. Helmbold (New York: Liberal Arts Press, 1952), p.103; Plato, Republic, 10.614b–621d, translated by C.D.C. Reeve (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004), p. 320; Plato, Phaedo, 107c–115a, translated by G.M.E. Grube (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1957) p. 58-59.

little literary merit: William R. Bascom, African Dilemma Tales (The Hague: Mouton, 1975), p.3.

the best and largest folklore collection: Michael Edward Bell, “Harry Middleton Hyatt's Quest for the Essence of Human Spirit,” Journal of the Folklore Institute, Vol. 16, No. 1/2 (Jan.-Aug. 1979, pp. 1-27). Passage quoted is on p. 13.

much of what his informants were telling him: Ibid., p. 15.

five thick self-published volumes: Harry Middleton Hyatt, Hoodoo-Conjuration-Witchcraft-Rootwork (Hannibal, Missouri: Western Publishing, Inc. 1970-78).

I did not begin with preconceived theories: Ibid., vol. 5, p. i.

Everything you want: Ibid., vol. 1, p. 157.

At exactly twelve o’clock on Friday night: Ibid., vol. 1, p. 100.

The reason I tell you that: This and below from Ibid., vol. 1, p. 99.

They called it his testimony: Annye C. Anderson, with Preston Lauterback, Brother Robert: Growing Up with Robert Johnson (New York: Hachette, 2020) p. 87.

Stand at the crossroads and look: Ibid., p. 74.

I will quote from Lee Irwin’s more reliable survey The Dream Seekers: Passages here from Lee Irwin, The Dream Seekers: Native American Visionary Traditions of the Great Plains (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994), can be found on pp. 143, 123, 83, 148, 151 152, 119 and 208.

great informative read ted. in 1998, I was interviewing Eddie Kirkland. he was best known as John Lee Hooker's guitarist from 1949-1962. out nowhere, he started talking about his visit to the crossroads. I sat in silence and awe in that I was hearing a first hand account of this belief, prevalent in the southern African-American culture, that up to this point, I'd only read about.

...here are Eddie's exact words.. "Almost all the people born on those islands, Jamaica and Cuba, held those beliefs passed down from generations. That’s most of their religion. In America, I was taught to worship Jesus. My mother’s people came out of Africa and they brought much of the African religion with them. My dad’s people came from Cuba, and they believed in the same things, root doctors, mojos, and crossroads.

I know what happened. Charley Patton years ago sold his soul to the devil and he lasted 5 years. Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil and lasted 8 years. Stevie Ray Vaughan sold his soul and lasted 6 years. Jimi Hendrix sold his soul to the devil and lasted 6 years. People read up on this stuff and they try it man.

I’m gonna tell you something. I went to the army in 1943. I came out in 1945. I was kicked out and I hurt so bad becauise I wanted to be a service man. I was really angry. I didn’t have nobody, I hadn’t seen my mother since I was 12. I went to Detroit. I went and got me a black cat, got me a big ol’ boiling pot and boiled that cat till the bones just fell offa her. Once you get that bone, you go to the fork in the road for nine mornings. If you can stand what you see for nine mornings, you’re automatically sold to the devil. If I’d a went through with it, I’d a been dead, gone, cause the devil woulda come and got me. What I saw on the first morning at the crossroads, I said, Hell no. I went to a priest who told me to get on my knees for nine mornings and ask God’s forgiveness and you’ll be alright. I did that cause what I saw on the first trip, I knew I wasn’t gonna go through with that.

Stevie was at the top of his life, Jimi was at the top of his life. Robert Johnson was at the top of his life, Charley Patton too. I backed out of that."

Hi ted -great to read your stuff - i have bought your blues book and subversive history and both are informative and insightful. Re the piece on Robert Johnson and in part the imagery derived from landscape that is found in the blues, I once had the inestimable privilege of having a long conversation with Brownie McGee at a post gig party in Dunedin New Zealand. This was way back in the early 1970s. To be honest I didn't know squat about the blues beyond the Peter Green/Clapton/BB King stuff but as I wrote music reviews for the Uni newspaper I got these invitations from to time.

The concert had been promoted locally by a pair of wealthy lawyers and it was in one of their big houses that the party took place. The atmosphere was a trifle odd as the host was keen to both show off his guest - Sonny Terry was tired and stayed in his hotel rather than attend - and equally keen to demonstrate his knowledge of the blues. He got into a conversation with Brownie about the details of his past. It was odd because this guy even had the temerity to correct Brownie's versions of some of these events. It became clear that Mr McGee found this tiresome and he retreated to a piano stool in one corner of the large room. A few of us kids - I was 19 - sort of gathered at this feet and he began to talk to us whilst still holding a sort of more public conversation with his host.

At one point a guy turned up with an ancient Gibson acoustic which he was keen to sort of flaunt to gain Brownie's validation as it were. The old man confided to us that he had several of this model back at his home and that he was "a dollar millionaire". He then offered the man a thousand dollars for the guitar but it became clear that the guy didn't want to sell it. Brownie kind of dismissed him at that point in a kind of "shit or get off the pot" manner - courteous but "don't waste my time or patronise me".

The atmosphere was getting odd as clearly Brownie wasn't interested in pandering to his hosts and again said to us kids that he was touring on behalf of the US State Department and encountered this sort of thing often. He obviously found these rich white folks somewhat patronising and repeated the point that, appearances to the contrary, he was a man of substance and not some kind of old poor black man singing for his supper.

Kiwis were then - before Peter Jackson's Tolkein tourism movies - inclined to manifest a sense of insecurity that whilst they lived in this demi-paradise, the world had largely ignored the place. So foreign visitors were often asked about what they thought of the country. Brownie deflected these questions in a courteous manner, being too diplomatic to offer any view that might court controversy. Apart from which he was on a whistle stop tour and hadn't really "seen" much of the country at all. These queries continued in an ever more fatuous manner - "What do you think of the mountains ?" - sort of thing until one of the hosts asked what Brownie thought of the rivers.

At this point Brownie presented a long disquisition, almost sotto voce, about his relationship to rivers and it became very clear to us kids that he wasn't talking about the Mississippi or the Hudson but dealing more with the imagery of rivers in the blues and in poetry and what those images denoted in a metaphysical sense. Most of the "grown-ups" quickly lost interest - he wasn't speaking in a loud voice - and returned to their conversations with each other. Brownie continued talking to us kids sat on the floor at his feet. He went off almost in a kind of reverie about the poetics of landscape in the blues. He didn't use those terms but that was the center of his meaning. He knew precisely what he was saying and had read the complexities of the room and the different degrees of receptivity in his audience(s) and his tone was definitely "Who feels it knows it".

It was at that point that my eurocentric conception of this music and its denizens took a giant step into the beginnings of the kind of understanding that your piece on Robert Johnson exemplifies. I knew intuitively that what Brownie was saying to us kids was on the same level as the lectures on the Metaphysical poets that I was attending at Uni. The blues never sounded the same since that night.