How Musicians Invented the Antihero

In this section from my new book 'Music to Raise the Dead', I probe the hidden musical origins of Hollywood protagonists

Today I’m sharing a section from my book Music to Raise the Dead. I’m publishing it in installments, and it’s currently available only on Substack.

Each chapter addresses a separate question, and can be read as a stand-alone article.

If you want to read the book in its entirety (or dig into previous installments), I’m sharing an interactive table of contents below.

I’ll publish the remaining sections of the book early next year.

MUSIC TO RAISE THE DEAD: The Secret Origins of Musicology

Interactive Table of Contents

Prologue

Introduction The Hero with a Thousand Songs

Why Is the Oldest Book in Europe a Work of Music Criticism? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Is There a Science of Musical Transformation in Human Life? (Part 1) (Part 2)

What Did Robert Johnson Encounter at the Crossroads? (Part 1) (Part 2)

Why Do Heroes Always Have Theme Songs? (Part 1) (Part 2) (Part 3)

What Is Really Inside the Briefcase in Pulp Fiction?

Where Do Music Genres Come From?

Can Music Still Do All This Today?

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Why Do Heroes Always Have Theme Songs? (Part 2 of 3)

By Ted Gioia

For centuries, heroes survived only in songs.

Homer was the Marvel Cinematic Universe of his day. And we find the same thing elsewhere, for example in the Epic of Gilgamesh or the Mwindo Epic or the Ramayana. You might say that heroes survived only if they were sung—because music served as cloud storage for traditional societies.

In the English-speaking world, the folk ballad stood out as the most important and enduring survival of the ancient hero’s tale. Even after the invention of the printing press, these songs still flourished in the aural culture—preserving the hero’s music even as it was forgotten by highbrow elites.

When folk song scholars Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles traveled to southern Appalachia during their 1916-1918 visit to the US, they were amazed to learn that old British ballads not only survived in this impoverished region, but often in a more authentic form than back in England. Here, four thousand miles away from home, they heard melodies of works that, in their land of origin, only existed as literary texts.

“The entries on ‘antihero’ in both Wikipedia and Encyclopedia Britannica make no mention of music whatsoever. But the lineage of this concept is absolutely clear—it came out of folk ballads and other traditions built on singing and rhythmic language.”

Sharp had not expected this, and later claimed his whole research trip had been a matter of mere chance—he had only come to the US to teach dance steps to Shakespearian actors and give a few paid lectures. But fortunately he followed up on a rumor, heard from a woman in North Carolina, who boasted that people in the backwoods still performed the songs their ancestors sang in England and Scotland. Sharp and Karpeles’s ensuing research uncovered an unbroken tradition of heroic music that had somehow resisted both the ravages of time and geographical displacement, surviving intact into the age of movies and recordings.

These folk ballads also defined a new type of protagonist, now known as the antihero—a familiar figure in film and pop culture, but also an invention of traditional singers. There are many antiheroes today, but before the rise of mass media, the most influential example in British culture was Robin Hood—who is a recurring character in the 305 canonic Child Ballads, playing a key role in 38 of them.

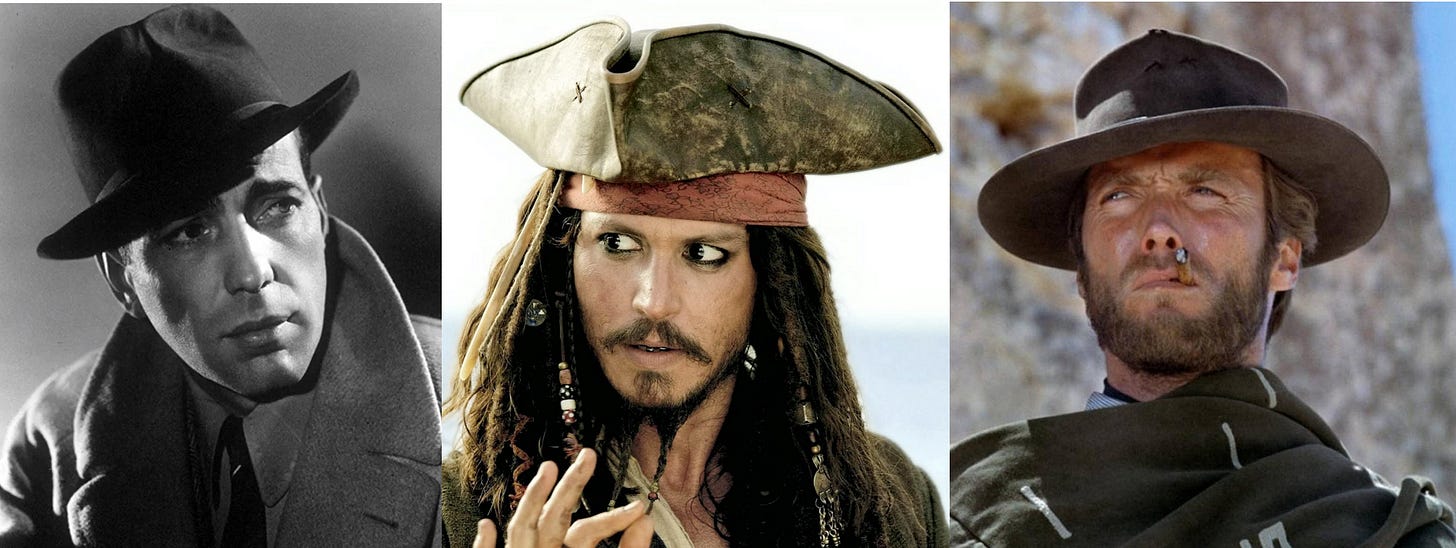

Without Robin Hood, there is no brooding Clint Eastwood in a spaghetti western or ironic Humphrey Bogart running a nightclub in Casablanca. Once again, a powerful cultural trope originates as a musical tradition.

That tradition had been around for roughly 500 years before Professor Child began collecting these songs. The most curious detail of these ballads is the fact that Robin Hood is both a hero and an outlaw.

Nowadays we are familiar with a criminal who is also a hero—this character shows up everywhere from Ocean’s 11 and Pirates of the Caribbean films to TV shows such as The Sopranos and Breaking Bad. Most cultural critics act as if the antihero is a modern invention—or even a quintessentially modern personality type. But this protagonist originated in songs and the oral tradition.

The antihero shows up in embryonic form in traditional tales of the Trickster, a familiar persona in myths, legends, and sung tales, most notably those found in Native American, African, and diaspora cultures. Homer also adopted some elements of the Trickster persona for his hero Odysseus, and we can identify this figure in many other societies. Yet the story took on realistic, quasi-historical trappings with the rise of Robin Hood as the dominant protagonist in the British folk ballad repertoire, probably toward the close of the fifteenth century.

The antihero has become such a powerful meme, that this conflicted character has suprassed the traditional hero in pop culture narratives. The shift is so marked, that the Joker—who first made his appearance in April 1940 as a cartoonish adversary in the debut issue of the Batman comic book—is now more popular than the caped superhero himself. Hollywood discovered this character type back in the 1930s and 1940s, and still milks it for everything it's worth.

Humphrey Bogart was among the first to grasp the possibilities of the antihero as a screen persona—but the 1950s and 1960s saw it take off. A whole series of brooding screen stars (Marlon Brando, James Dean, Paul Newman, Clint Eastwood, Steve McQueen, Jack Nicholson, and their countless imitators) were so successful in demonstrating the allure of moral ambivalence, that we still haven’t escaped their pervasive influence a half-century later. Compared to the complexity of the antihero, traditional heroism now seems shallow and one-dimensional.

The entries on “antihero” in both Wikipedia and Encyclopedia Britannica make no mention of music whatsoever. But the lineage of this concept is absolutely clear—it came out of folk ballads and other traditions built on singing and rhythmic language. But this is now forgotten or overlooked, even by people who claim to be experts on the subject. If you believe the conventional accounts, you might think that Hollywood stars and hard-boiled fiction writers had invented the antihero. In this regard, the hero and the antihero share the same fate: their music has been erased from the historical record.

Yet the musical connections of the antihero are more than just a matter of origins. In a very real sense, musicians stand out as the most powerful representatives of the antihero concept in popular culture. Back in the 1950s, Elvis Presley was a far more influential (and controversial) antihero than James Dean. In the 1960s, Mick Jagger shook up more people with his moral ambivalence than Clint Eastwood. A few years later, Sid Vicious and Kurt Cobain lived the antihero contradictions in ways that make Johnny Depp and Harrison Ford look like pretenders to the throne.

Just listen to the defining songs of these artists, from “Jailhouse Rock” to “Sympathy for the Devil” to “Anarchy in the U.K.,” and all those other antihero tunes still in non-stop rotation on playlists worldwide decades later, and consider their impact on the modern psyche. And it’s not just rock. Every music genre needed to find its own antiheroes to maintain relevance in the marketplace.

Country music fans called them outlaws and although this genre is supposedly a bastion of traditional values, its greatest legends are bad boys like Willie Nelson and Johnny Cash—who famously sang of killing a man in Reno “just to watch him die.” Or what about reggae and Bob Marley, who announced, in a famous song, that “I shot the sheriff.” And you couldn’t even begin to count the songs boasting about murder and violence in hip-hop and blues.

Robert Johnson is an antihero. Tupac Shakur is an antihero. Billie Holiday is an antihero. Even Glenn Gould is an antihero. Their mythos is as big as their music.

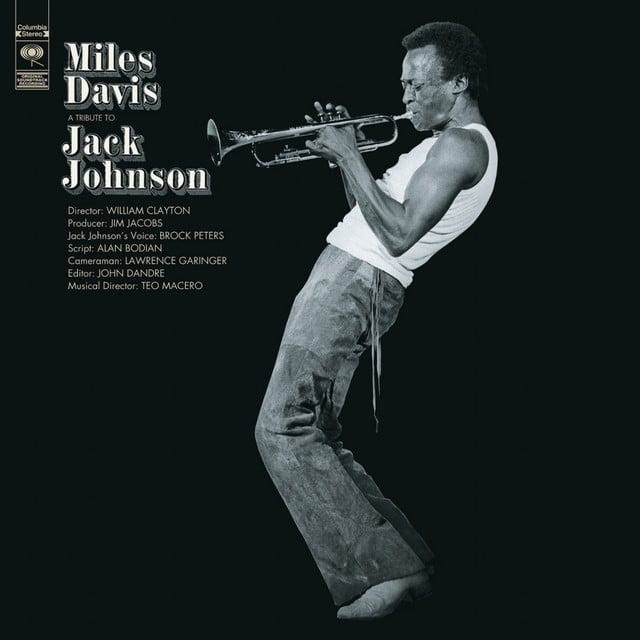

As the last example suggests, the songs themselves don’t need to be violent, or even have lyrics, to convey this ethos. If I had to pick the biggest musical antihero of all, I’d opt for trumpeter Miles Davis. Miles may have been famous for cool jazz, but was hot and intemperate in almost every other sphere of his life.

Yet that’s the paradox that drives the whole antihero meme, those simmering, unpredictable interchanges between fire and ice, sympathy and rage, the raw and the cooked. It’s the most potent persona in contemporary narrative, and it’s never lost its ties to music, although on the surface the two concepts—songs and antiheroes—appear to have nothing in common.

“Robert Johnson is an antihero. Tupac Shakur is an antihero. Billie Holiday is an antihero. Even Glenn Gould is an antihero. Their mythos is as big as their music. “

So it makes perfect sense that Robin Hood and the antihero tradition would emerge from the folk ballad. This protagonist was famous for stealing from the rich and giving to the poor—and what narrative tradition was more aligned with the underclass than that? But Robin Hood could never have been a movie hero if he hadn’t first been a musical one.

These ballads were preserved and promulgated by the impoverished, people who had no access to novels—and not just because they couldn’t afford them. In many instances, they lacked even the basic education necessary to read them. Music and dance have always been the central forms of artistic expression for this underclass, and it’s hardly surprising that they would inherit a tradition that celebrated heroes of knights and noble ladies, but add to it a new twist—reversing the values of elites and insiders.

This is a huge unexplored gap in cultural history. The rise of the antihero completely changed the rules of narrative, and musicians have never received fair credit—or, in many instances, any credit at all—for this innovation.

But the influence of Robin Hood, for all its importance, can hardly match that of King Arthur and the knights of his famous Round Table. King Arthur had a different moral valence, more aligned with the establishment—after all, what do you expect from the King? But between them, these two figures—Robin Hood and King Arthur—defined almost the entire rulebook for modern protagonists in film, video games, and other narrative-driven media.

“King Arthur is the first business-driven brand franchise in Western culture. He may have originated as King of the Britons, but he thrived as Servant to the Capitalists….And this had a terrible impact on music.”

If Robin Hood wrote the playbook for the antihero, the Arthurian legends created a more mainstream, if less ethically nuanced, approach to the mass-market heroes that dominate today’s pop culture. One of the best measures of the influence of the Arthurian tradition is the sheer number of heroes it presents, not just King Arthur and his multifaceted wife Queen Guinevere, but also the many knights of his Round Table. These include Lancelot, Gawain, Percival, Tristan, Galahad, and dozens of other heroes celebrated in countless songs and stories. They represent, in aggregate, every twist and turn of the hero’s journey.

But even more impressive is how many nations have claimed these heroes as their own. Most readers associate King Arthur with England, but the Welsh have a much better claim to him—there’s a whole school of thought that traces the origin of his story to a Celtic deity. And some scholars even link Arthur back to a Romano-British leader who battled the invading Anglo-Saxons. In other words, King Arthur might originally have been an anti-Anglo hero who took pride in his connections with the colonialist Caesars.

But here’s something even stranger: the greatest early literary accounts of the Arthurian tales came out of France, England’s most hated rival (the Hundred Years War was still a living memory)—where they were popularized by the famous trouvère Chrétien de Troyes and other court bards. This cultural displacement led to one of the most unexpected twists in literary history. Sir Thomas Malory established King Arthur as the preeminent British hero, but his publisher William Caxton even gave the book a French name (Le Morte d'Arthur) and openly admitted that the stories came from French sources.

Yet Caxton noted that other Arthurian accounts could be found in Spanish, Dutch, Italian, and Greek. And the German angle is especially compelling. Richard Wagner drew again and again on Arthurian tales and turned them into foundational myths of his own national culture. Then finally King Arthur traveled to America, and shows up everywhere from Hollywood to Broadway.

If you are seeking a universal hero in the psyche of Western culture, this is the closest prototype you will find.

For our purposes, the Arthurian legend is of particular importance—as will be seen even more clearly in the next chapter, where everything from The Maltese Falcon to Pulp Fiction will be explicated with help from this forerunner. At this stage, it’s important to stress that Caxton did all this to make money. He was the first person to introduce a printing press into England, and his goals were commercial and mercenary. Caxton wasn’t a folklorist but the owner of (what we could call nowadays) an entertainment business. King Arthur and his valiant knights were his brand franchise (to use another contemporary term).

In fact, King Arthur is the first business-driven brand franchise in Western culture. He may have originated as King of the Britons, but he thrived as Servant to the Capitalists.

And this had a terrible impact on music.

Because of Caxton and his brand franchise, heroes now had to abandon their songs. And for the saddest (and simplest) reason of them all: you can’t sing on the printed page of a mass-market, text-driven narrative.

And we lost so many other things from this shift. The hero’s journey could no longer focus on acquiring wisdom—instead it required constant fights and bloodshed, love affairs and adultery, rivalries and vengeance. You needed those ingredients to sell books (and later movies, video games, etc.).

The visionary power of sleep and dreams (so essential to the shamanic musical tradition where heroic narratives originated) also was forgotten. Caxton imposed all these changes on his market-driven heroes in order to maximize profits. We’re still paying the price today.

It’s not a small thing to abandon the quest for wisdom and transcendence.

But that’s exactly what happened. After the Arthurian rupture, metaphysics had no place in popular culture. Music survived—it was impossible to kill—but mostly cut off from its own nurturing roots. Songs were now products for commerce, not pathways for self-transformation.

I sometimes wonder how different our culture would be if recording devices had been invented before the printing press. Singing bards might have enjoyed wider renown and more acclaim than scribblers of novels. The aural/oral tradition would be enshrined in great institutions—universities, libraries, archives—and songs would be treated as the cornerstone of the humanities, and not as an afterthought. Scholars studying the lineage of the epic, the lyric, the troubadour song would treat them as essentially musical forms of expression, and not as literary works flattened by their reduction to black-and-white words on the printed page.

Above all, heroes would never have lost their songs.

Yes, they still survive nowadays. But only as simulacrums—theme songs in a movie or video game. But they were once so much more….

Holiday gift subscriptions to The Honest Broker are now available.

Click here for Part 3 of “Why Do Heroes Always Have Theme Songs?”—where I look at how Western literary culture went to war against music in a battle that continues to impact us today.

This makes a great deal of sense. Our current musical environment looks to be a concerted effort to squash the concept and personae of the antihero. It seems clear that the streaming/digital music environment also illustrates the tendency of technology to damage culture and allocate non-tech-related centers of money to itself. It's no accident that the technology business scene is fully populated by monopolies and oligarchies. To a one, these agents enforce conformity and compliance. Streaming companies act as fronts for this baleful cultural trend. The anithero has likely never faced such a powerful and dangerous adversary.

So nice...! A little less famous than Miles but perhaps as similarly iconic as anti-hero wd be Mingus, no?!