Western Music Isn't What You Think

Or how my views on culture proved to be all wet

Around 1990, I started researching the social history of music. I knew this was a big topic, but I had no idea how big.

As it turned out, this project kept me busy for the next 25 years.

I was crazy to do this. I was trying to understand the role of music in human life going back to prehistoric times, and hoped to follow its evolution until the present day. This demanded intense multidisciplinary research at a scope beyond anything I’d attempted before.

Nobody wanted me to take on this mission. In fact, I’ve never faced such resistance in anything I’ve ever done.

Every publisher and editor I met during that period asked me to write about jazz—because my book The History of Jazz was a big seller and they wanted another book just like it.

When I tried to enlist their support for my bigger project, speaking in rapturous terms about music as a source of enchantment and change agent in human life, their eyes glazed over.

They didn’t want to hear it.

If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a premium subscription (for just $6 per month).

But I was persistent. This project was my obsession, and my motivation kept getting recharged—because I was learning things about music that other experts had missed.

Most of my breakthroughs came through sheer perseverance, and relentless digging into primary sources (usually outside of the music field) that my peers had never even considered consulting.

Even today, I reap benefits from this intense work. I gained a deep understanding of how culture impacts actual flesh-and-blood people—that’s the core of my expertise. I often draw on it for what I publish on The Honest Broker.

But it took me fifteen years before I was ready to share the first results of this massive research project—Work Songs (2006) and Healing Songs (2006). Almost a decade elapsed before I was ready to publish the final installment of this trilogy, Love Songs (2015). These works, encompassing the entire history of human song, prepared me to write Music: A Subversive History (2019).

I believe this is the core of my life’s work.

The book I’m currently publishing in installments on Substack, Music to Raise the Dead, is the culmination of this enormous endeavor. It presents nothing less than an alternative musicology—a powerful way of transforming songs into sources of enchantment and a life-changing force for individuals, communities, and entire societies.

I’ve learned many things during the course of this work, but one of the most surprising relates to how musical innovations take place.

I repeatedly encountered exciting new song styles emerging in port cities, border regions, and the fringes of society—both geographical fringes and poor fringe population groups.

The best known examples come from the Americas. The dominance of US commercial music in the last hundred years relies, to an extraordinary degree, on African Americans. Their contributions led directly to jazz, blues, soul, hiphop, R&B, Afro-Cuban music, and a range of other important idioms.

Put simply, the most impoverished, marginalized people had the greatest impact on the music.

I always just took that for granted. But it’s surprising, no?

In the course of my research, I kept encountering the same influence of the outsider. I found it everywhere from the emergence of secular songs in Deir el-Medina in ancient Egypt to the rise of tango in Buenos Aires or reggae in Jamaica.

The outsider is everywhere in music history.

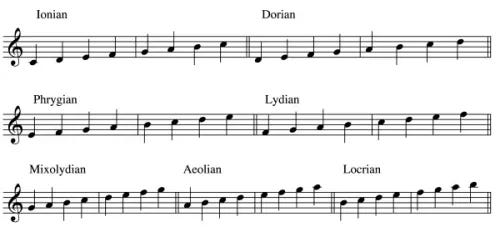

Consider, for example, the names of the musical modes—something else I long took for granted. They are named after population groups, but who were the Aeolians, the Lydians, and the Phrygians?

They were slave groups, conquered by the Greeks in Asia Minor. The Greeks also named some modes after themselves, but the more unusual or controversial modes were associated with slave musicians.

They don’t teach you this in music school.

So the next time you hear somebody talk about the building blocks of Western harmony, show them the map below. It’s not as Western as they think.

They will see that a dialogue between insiders and outsiders was shaping European music long before Europe even existed as a concept.

Now let’s examine the origin of the Western lyric song. The most significant innovator in the history of this idiom is Sappho, a singer-songwriter (if I can use the current-day terminology) who lived on the island Lesbos, circa 600 BC.

But Lesbos is on the absolute fringe of Europe, and is even today an entry point into the continent from West Asia. In 2015 alone, a half million migrants from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq arrived on Lesbos.

It’s safe to assume that Lesbos was also home to a diverse population in Sappho’s day, with strong ties to West Asian musical traditions.

You might say that Lesbos is like New Orleans, where jazz originated. The ingredients for innovation were the same in both instances:

Located at a port on a major trade route

At a border point or boundary between countries/cultures

Boasting a diverse, multicultural population

New Orleans was the most diverse city in the United States at the time when jazz emerged. The population drew from Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, and Latin America—and this diversity was further supported by a constant flow of trade and visitors via the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico.

“Cultural historians rarely pay attention to water, but they really should.”

It’s no coincidence that jazz happened here. This is precisely the kind of city where new musical styles evolve.

But let’s go back to Europe—because the story gets more interesting.

In a surprising passage from The Philosophy of History, Hegel recognized the key role of outsiders in the formation of Western culture. “The rudiments of Greek civilization are connected with the advent of foreigners,” he writes. He even identifies the main source of its success, and sums it up a single word: heterogeneity. Today we might call it diversity.

This pattern would repeat itself over and over in later centuries.

The most significant innovation in Western love songs after Sappho came from the French troubadours during the late medieval era. But how much of this music originated in France?

Related Articles:

Did Bach Draw on Native American Traditions?

Is There Such a Thing as Western Harmony?

The Most Important City in the History of Music

Why Did Medieval Cities Hire Musicians as First Responders?

I was shocked to learn, during the course of researching my book Love Songs, that this deeply personal approach to singing about romantic love actually originated in Baghdad among female slave singers—slaves again as song innovators! And it only entered Europe via Spain after the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

From there, the song styles came to the south of France, and then got disseminated throughout Europe. The French nobility took all of the credit, and most books still present the story from that perspective. But in reality, innovation took place at the fringes, and entered Europe via outsiders.

I’ve written elsewhere about Córdoba, which had the largest population of any European city in the 11th century. That surprises many people—but Córdoba had more people than London, Rome, and Paris combined.

Take a guess at answering this question: What were the five most populous cities in Europe in the year 1050 AD?

You’re in for a shock. Here’s the list:

Let’s put those cities on a map.

This is where secular culture emerged in Europe, laying the foundation for Western humanism and the Renaissance. But you’re gazing at Palermo and scratching your head.

Yet it’s true: Palermo had a population ten times as large as Rome back then.

I need to emphasize this point: the exciting centers of European culture during its formative years were port cities, or borderlands, or other multicultural centers. Innovation came into Europe from outsiders, especially via the Mediterranean and Adriatic seas.

Just stop and think for a moment about the importance of Venice in the history of music. Everything from madrigals to operas found their home in that bustling port city—a key connecting point between West and East in the modern imagination.

And what about Rome? In ancient times, Rome had been a dominant source of culture and innovation—but that only happened when all roads led to Rome (as the proverb goes). When Rome was a diverse, multicultural center, it exerted enormous influence. But when it lost its allure as a destination for outsiders, during the medieval era, Rome stagnated.

Rome later regained its luster. But that only happened when a new influx of outsiders showed up there. The same is true of Paris, London, Vienna, etc.

I’m focusing on music here, but the same forces shaped innovations in literature. For example, the sonnet—which we all associate with Petrarch and Shakespeare—actually originated in Sicily. It started on the fringes of Europe, and then migrated inland.

And if I had time, I could discuss how religious movements always entered Europe from outside—all those Roman mystery cults came from other countries and cultures. Even Christiantiy—which many people view as emblematic of European culture—arrived in Rome from West Asia.

This is the truth about Western culture nobody wants to tell you. People treat it like a monolithic system of established elites, but the exact opposite is true.

Let me lay it out for you:

Western culture only thrived because it drew on diverse outsiders.

The major sources of innovation are often located on the fringes of the Western world, because this is where outside influences enter the system.

Cultural historians rarely pay attention to water, but they really should. For example, the Mediterranean was a huge force in innovation and cultural transmission, but rarely shows up in your typical Western culture class.

It’s no coincidence that Greece—which has the largest coastline of any country in the entire Mediterranean region—was the epicenter of innovation in the classical world. Those 8,500 miles of shore land are a measure of Greece’s openness to the outside world.

The most innovative cities are also the most diverse, and not because diversity is a popular political slogan, but due to the simple fact that we evolve as a species by sharing and learning among others with different backgrounds.

Poor, disadvantaged groups have a huge impact on this process, because they make up a significant portion of the population in these borderlands. These include migrants, exiles, slaves, and other marginalized communities.

Given this process, even the term Western culture is misleading—because so much of it came from outside the West, strictly defined.

But this isn’t a flaw in the system. It’s actually a great strength. A culture that can assimilate the best of outside forces is stronger because of that skill.

I know this is true for music—because I’ve done the research. But we have good reason to believe that other spheres of culture follow a similar pattern.

I share this because I want to defuse some of the hostility to this cultural history. We don’t need to choose between ‘Western’ culture and diversity—they go hand-in-hand. The problems begin when we forget that important fact and start living (and thinking) in silos.

Everybody bitches about cultural appropriation. But you know, bite me. Because what it really is is cultural cross-pollination and it's where everything important to art, architecture, music, science, and language comes from. Think of it as cultural endosymbiosis. Thanks for all you do Ted!

My own researches have been focused upon Irish music, traditional and otherwise (a nod to Tin Pan Alley) over the years - which also claims a role in both instruments and dance steps relating to Jazz and its ancestry. I defer to those more expert in the latter, but I am reminded of a book about the Irish in America titled "How the Irish Became White" which reflected early years of discrimination in the US affected the role of the Irish in American society and how they evolved out of that early niche.