The Most Important City in the History of Music Isn't What You Think

We can learn from the Córdoba Miracle—and not just about music

Which city is our best role model in creating a healthy and creative musical culture?

Is it New York or London? Paris or Tokyo? Los Angeles or Shanghai? Nashville or Vienna? Berlin or Rio de Janeiro?

That depends on what you’re looking for. Do you value innovation or tradition? Do you want insider acclaim or crossover success? Is your aim to maximize creativity or promote diversity? Are you seeking timeless artistry or quick money attracting a large audience?

Ah, I want all of these things. So I only have one choice—but I’m sure my city isn’t even on your list.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

My ideal music city is Córdoba, Spain.

But I’m not talking about today. I’m referring to Córdoba around the year 1000 AD.

“Did you realize that Córdoba was ten times larger than Rome? Medieval Paris and London are tiny villages by comparison.”

I will make a case that medieval Córdoba had more influence on global music than any other city in history. That’s probably not something you expected. But even if you disagree—and I already can hear some New Yorkers grumbling in the background—I think you will discover that the “Córdoba miracle,” as I call it, is an amazing role model for us.

It’s a case study in how communities foster the arts—and in a way that benefits everybody, not just the artists.

First, I need to provide some background on the sources of musical innovation. Over the course of three decades of research into this matter, I kept encountering new styles of song emerging in unexpected places—but these locations always had something in common.

These epicenters of musical innovation are always densely populated cities where different cultures meet and mingle, sharing their distinctive songs and ways of life. This intermixing results in surprising hybrids—new ways of making music that nobody can foresee until it actually happens in this hothouse environment.

New Orleans provides a great example. Around the time jazz originated in New Orleans, it was the most diverse city in the world—an intense intermixing of French, Spanish, African, Caribbean, Latin American, and other cultures. And the mixture was enhanced by the huge number of travelers and traders who came to the region because of the prominence of the Mississippi River as a business and distribution hub.

Here’s how I described this process in the appendix to my book Music: A Subversive History, where I shared 40 precepts on the evolution of human songs.

I wish I had time to defend these assertions here with empirical evidence. But we don’t have the space to do that. Let me say, however, that these statements are amply documented and supported with dozens of examples and case studies in the course of that book.

But here I want to make another point: namely that a thousand years before New Orleans spurred the rise of jazz, and instigated the Africanization of American music, a similar thing happened in Córdoba, Spain. You could even call that city the prototype for all the decisive musical trends of our modern times.

“This was the chapter in Europe’s culture when Jews, Christians, and Muslims lived side by side,” asserts Yale professor María Rosa Menocal, “and, despite their intractable differences and enduring hostilities, nourished a complex culture of tolerance.”

There’s even a word for this kind of cultural blossoming: Convivencia. It translates literally as “live together.” You don’t hear this term very often, but you should—because we need a dose of it now more than ever. And when scholars discuss and debate this notion of Convivencia, they focus their attention primarily on one city: Córdoba.

It represents the historical and cultural epicenter of living together as a norm and ideal.

Even today, we can see the mixture of cultures in Spain’s distinctive architecture, food, and music. These are both part of Europe, but also separate from it. It is our single best example of how the West can enter into fruitful cultural dialogue with the outsider—to the benefit of both.

I first became aware of the significance of Córdoba while researching my book on the history of the love song. According to most accounts, the main features of the modern love song can be traced back to the troubadours of Southern France in the late medieval era. Yet my studies kept revealing that these French nobles had borrowed this way of singing from medieval Spain.

Nobody could trace this lineage clearly before 1948, when an Oxford grad student named Samuel Stern managed to translate previously indecipherable lines in 11th century Spanish songs. He found that these songs were hard to understand because they combined vernacular Romance language phrases (a kind of prototype of Spanish) with Arabic and Hebrew lyrics. They only made sense—and revealed their meanings—when treated as cultural fusions.

Even more striking, these were intensely personal love songs of a shocking degree of intimacy for the medieval era—some of them very similar to what you might hear even today. My further research detected a previously unnoticed migration of female slave singers into medieval Spain from Baghdad and North Africa. These women were singing the equivalent of troubadour lyrics more than a century before these songs flourished in France.

In other words, the love song—the most popular kind of song for the last thousand years—was the result of a cultural melting pot in which Spain was the linchpin. Europe learned this way of singing by imitating this Spanish example, and in time this style of romantic song spread all over the world.

In an especially shocking chapter in music history, an African named Ziryab set up a music school in Córdoba in the early ninth century. This should be widely known and celebrated today, because Ziryab could even be called the originator of the music conservatory. But that only begins to describe his significance.

We would love to know more about Ziryab’s background and teaching practices (and I plan to write about that subject at a future point). But I note that his name Ziryab was a Persian translation of the word for blackbird—so we can be certain of his African or African-Arabic heritage. Yet we don’t need to know the nitty gritty details to marvel at an Africanized music school in Europe a thousand years before Juilliard was founded.

Córdoba had always absorbed multicultural influences. The city had been a Roman provincial capital during ancient times—there was a Roman forum there as early as 113 BC. A hoard of silver objects from that period makes clear that Roman and local artistic traditions were already intermingling. The city later became part of the Byzantine Empire, and then drew on Germanic influences after the Visigoth conquest of Spain.

But if you’re looking for a medieval case study in multicultural creativity—still an enormous challenge and opportunity in our own time—nothing compares to Córdoba after exiled Abd ar-Rahman, founder of Umayyad Arab dynasty, arrived in the Iberian Peninsula in 756 AD.

Because the ruling Islamic class only represented around 1% of the population in those early years, they were forced to absorb local influences. Over time, a huge number of locals converted to Islam, but that meant that almost everybody had relatives from other religions, and often close family members. Tolerance was not just a theoretical concept for these people, but a necessary way of life.

That’s why we find songs that straddle Arabic, Hebrew, and homegrown Spanish traditions. This alone would make Córdoba worth studying and emulating. But there’s another fact—a huge fact—that we must consider. And it’s probably something you have never heard before, and will hardly believe.

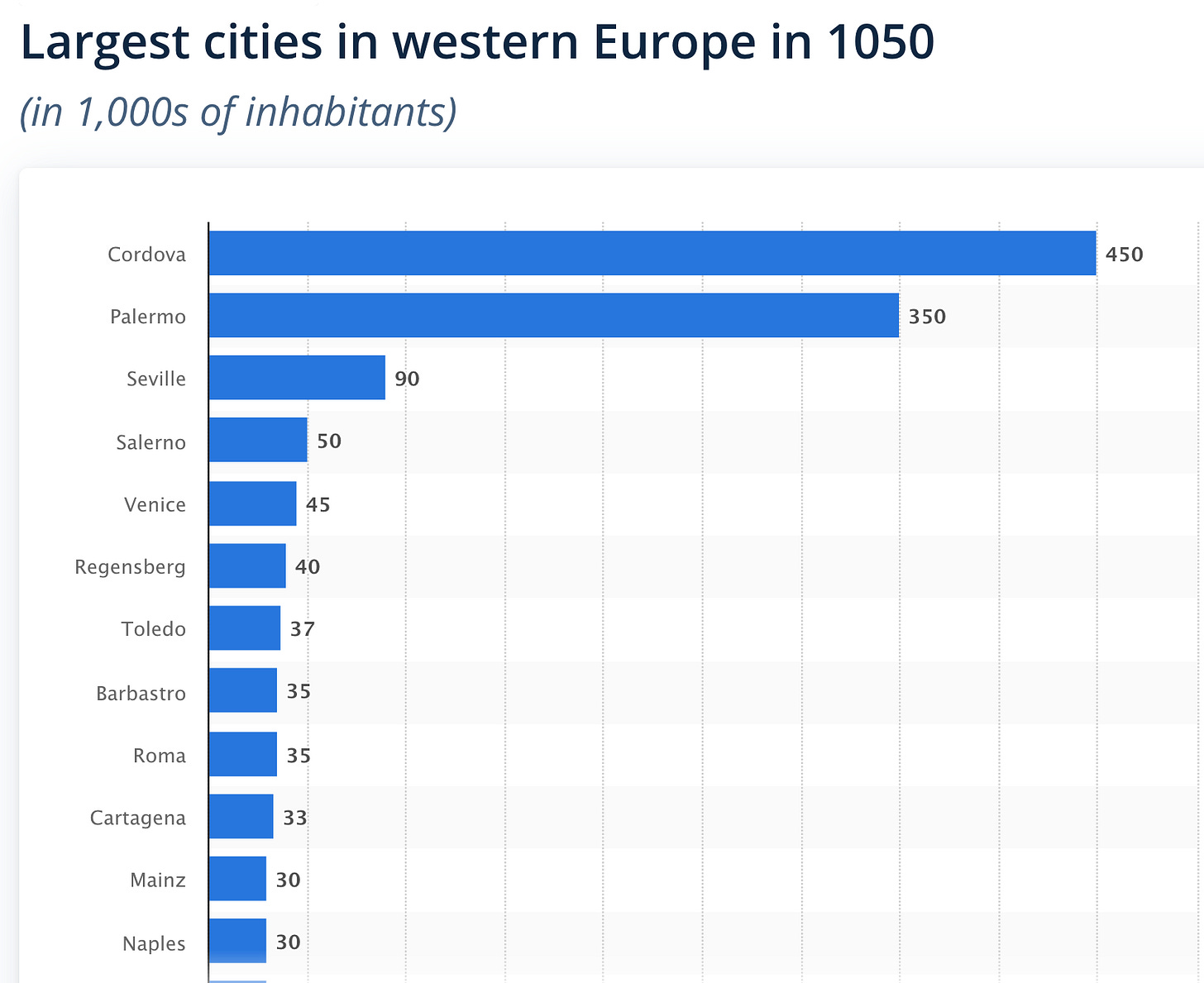

I’m referring to the fact that Córdoba had the largest population of any city in the West back in those days. Consider these estimated population numbers from the year 1050 AD.

Did you realize that Córdoba was ten times larger than Rome? Medieval Paris and London are tiny villages by comparison.

The world back then was driven by the Mediterranean, and that meant for much more fluid interactions between African, Arabic, and European cultures—and no place exemplified this more vibrantly than Córdoba. There were earlier examples of this intermingling in history—for example, the Egyptian village Deir el-Medina in the 18th to 20th dynasties of the New Kingdom. Or later ones, such as Venice during the Renaissance or New Orleans and New York in the 19th and 20th centuries. But they are all following the Córdoba model—which fosters artistic breakthroughs that don’t happen in more homogenized settings.

For this reason, I tend to view Córdoba as a prototype for the artistic environment that has flourished in the United States during our own lifetimes. But when we lose our sense of living together—our own Convivencia—we put all that at risk. And that impacts much more than music.

So the Córdoba Model, as I call it, is not just relevant in our own day, but intensely relevant—because the Internet is turning every city into a multicultural environment. Each city is its own global hub, both absorbing and providing creative impulses to the rest of the world.

The role model we need isn’t hard to describe—the rules are tolerance, connectivity, interaction, sharing, a welcoming attitude to new peoples and influences. But it’s apparently a hard model to put into practice in the real world—and even places where it once flourished seem to have forgotten its beneficial lessons.

Yet that’s one of the advantages of history, even music history: You don’t just study the past, you learn from it too. And the Córdoba Model still has something to teach us today. If we flourished by living together a thousand years ago, why shouldn’t it happen again now?

Ted, reading this stuff feels like someone opened a window and fresh air fills the room. We need signs of humanity's ability to be more than a pack of hyenas.

It's interesting to note that I always used to listen to a fantastic Paco de Lucia album called Zyryab. I had no context about the meaning of that word until now!