"This Is a Hell of a Statement I'm About to Make—But He Superseded Miles"

More on the mystery of Dupree Bolton, and updates on other recent articles.

Below are updates on several recent posts—and I cover a wide range of topics.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

I’ve griped a lot about the fake artists problem at Spotify. It’s like a stone in my shoe, and just gets worse and worse.

I’m especially alarmed by those strange playlists—filled with mysterious artists who may not really exist, or almost identical tracks circulating under dozens of different names.

Here’s a new example—a 20 hour playlist called “Jazz for Reading.”

I’m supposed to be a jazz expert. So why haven’t I heard of these artists? And why is it so hard to find photos of these musicians online?

I listened to twenty different tracks. There’s some superficial variety in the music, but each track I heard had the same piano tone and touch. Even the reverb sounds the same.

But the musicians are allegedly different.

Of course, I haven’t listened to the whole playlist. It feels endless, lasting almost an entire day!

But what’s going on here?

In other fields, this would be a scandal.

Imagine if you ran a medical office with physicians’ names on the door, but patients never got a glimpse of a flesh-and-blood doctor. Or a law firm gave out legal advice, but no lawyers were ever seen in the office.

Maybe Spotify will allay my concerns by putting these “artists” on tour. Why do I doubt that will happen?

A few days ago I published part one of my account of the mysterious jazz trumpeter Dupree Bolton—who shook up the LA jazz scene in the early 1960s, and then vanished.

I’ll soon share part two of that story.

In the meantime, check out this amazing account of Bolton from Curtis Amy, who hired the trumpeter shortly before his disappearance.

This comes from an oral history conducted by Steve Isoardi. I’m indebted to subscriber Tim Campbell, who called my attention to this document.

[Bolton] came down to the club and played and just blew everybody away. This young man was so talented. But there was a degree of cockiness that defeated him, because he thought he was the king of the world….

But he didn't get along with anybody, and it's really unfortunate, because to me, now I mean, this is a hell of a statement I'm about to make. But to me he superseded Miles [Davis] from the standpoint of playing…..

And he had all the love. Everybody loved Dupree, everybody—all the cats, all the girls….So it was just one of those bad situations in life that could have really been extraordinary, you know? Because we could have taken that band on the road….

But then I got Tuesday nights at Shelly's Manne Hole….and it would be packed. This particular Tuesday night I used Dupree and the band that we had played with on Katanga! We played the first set, man, and it was just burning.

It was just—whew, man! You know those unforgettable evenings that you have musically that are rare? Well, that's the way it was the first set.

We took intermission and I never saw Dupree again.

Some time back, I wrote about the remarkable piano prodigy Austin Peralta (1990-2012) in my article “The Jazz Great Who Never Was.”

Peralta was such a modest young man—I reached out to him as a music critic who hoped to write about his work. But he didn’t want me to hear to any of his recordings.

He insisted they weren’t good enough.

You can judge for yourself. Here he is at age 16—recording with Ron Carter. Peralta’s solo starts at the one minute mark.

Breathtaking, isn’t it?

I’ve never encountered such shyness from a recording artist. I had to order his albums from Japan because he refused to provide me with even a single track.

I’m convinced Austin Peralta would be famous now, if he had lived. He was closely involved with the Brainfeeder label (Flying Lotus, Thundercat, Kamasi Washington, etc.), and that would have opened doors. I suspect he would have played on The Epic, and recorded with many of the music superstars who live and work in SoCal.

I am happy to report that Peralta’s only leader date for Brainfeeder Endless Planets is getting reissued today in a new expanded edition.

Endless Planets deserves recognition as one of the classic jazz albums of the last quarter century. My only complaint is that Peralta didn’t feature his own playing enough on his own album—but that doesn’t surprise me, given my interactions with this unassuming virtuoso.

In December, I made predictions about a shift in the media during 2024. I anticipated that this year would witness a tipping point—marked by rapid weakening of the macroculture (traditional legacy media) and a huge increase in the power of the microculture (alternative platforms, such as Substack).

We’re only six weeks into the year, and here’s the bloodshed we’ve already seen.

Time magazine eliminated 15% of its unionized editorial staff.

Chicago Tribune suffered the first employee strike in its 180-year history.

TikTok refused to make concessions to Universal Music, and the largest record label in the world is now gone from this fast-growing platform.

Pitchfork’s corporate owner Condé Nast announced that the entire magazine would be absorbed into GQ.

Business Insider got rid of 8% of its staff.

There’s even a rumor about a network canceling its nightly news.

Meanwhile Spotify gave a new $250 million contract to Joe Rogan. And I keep hearing stories like this and this and this about successes on emerging platforms.

Welcome to the new normal—and we are only a few weeks into the year.

When Spotify first listed its shares on the stock exchange, I expressed skepticism about its business model—declaring that “streaming economics are broken.”

I did the math. The numbers told me that you simply can’t offer unlimited music for $9.99 per month. Somebody would get squeezed—probably the musicians (for a start).

And now?

I note that Spotify has sharply increased its subscription price and recently laid off 1,500 employees.

But the company released quarterly earnings this week—and it is still losing money!

Meanwhile the CEO continues to sell his shares—another $57.5 million in the last few days.

Let me put this into perspective: Spotify was founded in 2006, and has now been operating for almost 18 years. It has 236 million subscribers in 184 countries. But the business still isn’t profitable.

I expect that Spotify will find a way to make money, sooner or later. But the company has already squeezed subscribers and musicians. So who gets squeezed next?

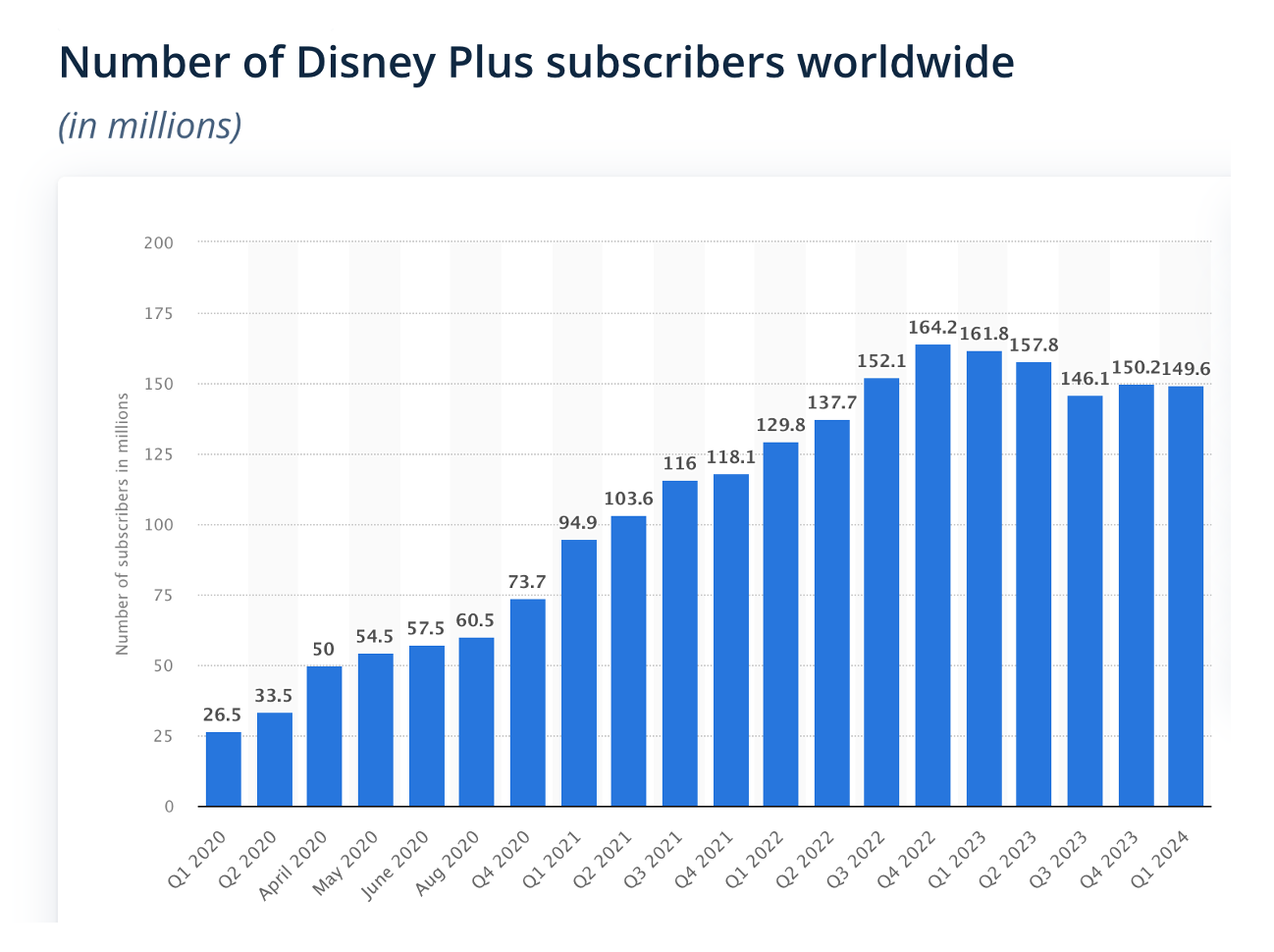

How easy is it go gain new streaming subscribers?

Check out the trendline below for Disney+. All signs indicate that large streaming platforms have hit a saturation point.

Disney’s quarterly results last week showed flat revenues, which missed expectations. Profits were still up, but only because of deep cost cutting.

This is just one more facet of the macro-versus-micro shift mentioned above.

I continue to anticipate a tech takeover of Disney, probably by Apple. But that company has its own problems to fix.

In October, I heard from angry Apple fans after I claimed that the company “will struggle to grow sales just 5-10% annually—unless they make a bold move. By comparison, Steve Jobs generated 44% compounded growth during the last five years of his life.”

As it turned out, I was too generous. The latest quarterly results came out this week, and Apple reported sales growth of only 2%.

Here’s a comment from subscriber Victor Sanchez to my recent article on the collapse in music journalism.

What I have noticed in my local paper, you may have heard of it, the New York Times, is no reviews of concerts and club dates that would have had a regular review years ago.

Regular reviews of musicians at The Village Vanguard would be common. If a major jazz artist like the Keith Jarrett Trio was at Carnegie Hall there would be a review a few days later.

Now there is nothing. Those reviews would encourage me to go hear a band or just inform me of what was happening. And if the review was of a concert I had attended the review would offer a different perspective on the music.

In the last month I saw, Kris Davis, Jason Moran, and Joe Lovano and not a single review of any of them. And this has been going on for years.

It seems they all have podcasts and year end lists, and write about cultural impacts, but nothing about live performances.

Upcoming concerts will be Vijay Iyer, then Ulysses Owen Jr. and Caetano Veloso in April and I'm pretty sure there won't be a review of any of their performances.

That’s a fair assessment. I check out the jazz news in mainstream media every day, and live music reviews simply don’t exist anymore, even in large cities.

Once again, blogs and Substacks are trying to compensate for this. But it’s a huge hole to fill.

My doom and gloom predictions about investment firms buying out song catalogs are all coming true. The CEO of the largest song investment fund lost his job last week. The fund is worried about litigation.

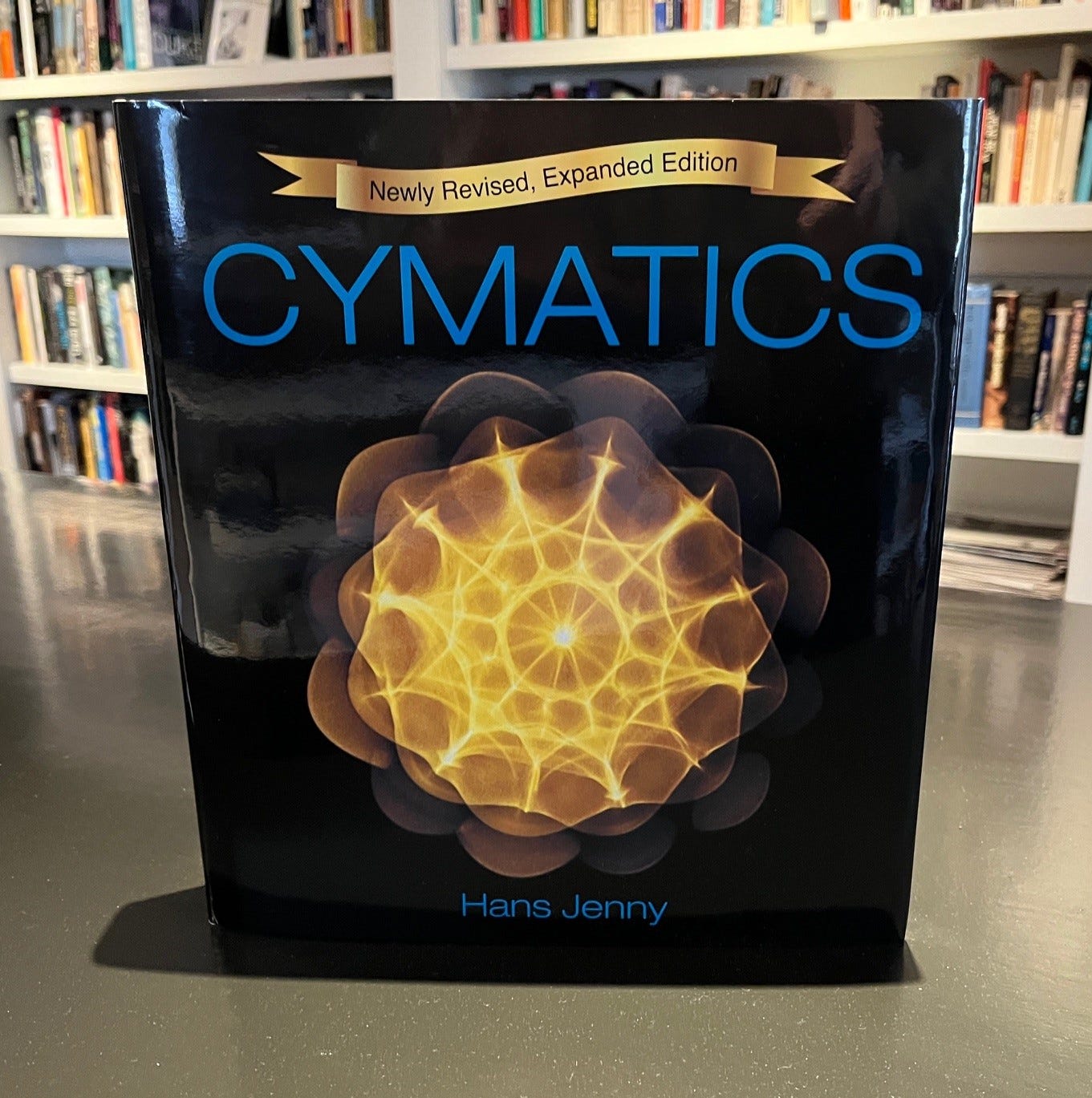

I’ve written frequently about Hans Jenny and his book Cymatics—one of the most important works on sound and music published during the last century.

I’m pleased to report that the long-awaited updated edition of Cymatics is finally available (with a foreword by me). My copy arrived in the mail this week.

Jenny’s research broadened my horizons, teaching me that music could transform physical reality. He actually capture it on film.

If you don’t know about Cymatics, this new edition is the place to start.

Just another example of the 'Enshitification' of our world.

Started with social media, now spreading everywhere like a toxic weed.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enshittification

Speaking of stolen or hacked music, and I’m sorry I don’t have a link for the New York Times, but there was an article about a band, called Bad Dogs, who found out that their songs were stolen and renamed, and someone had taken the digital fingerprints. It took them some time to prove that it was their music and this happens all the time. It is said that people that do this end up walking away with about $25,000 in royalties before they actually get caught.