The Final Triumph of Cormac McCarthy (1933-2023)

The novelist delivered an end-of-life masterpiece, but the culture machine was barely interested

Some years ago, I was doing a book promotion tour, and my driver dropped me off early for an event at one of the largest indie bookstores in the country. I tracked down the store owner, and we both had time to kill. So we embarked on a far-ranging conversation about novels.

The owner was just as passionate about books as me. It wasn’t just his job, it was his fixation. He was obsessively interested in contemporary fiction—and for a good reason: he often hosted the leading novelists of the day in his store. He knew them both as writers and individuals.

He had stories to tell, and I couldn’t hear enough of them. I felt like a junkie who gets introduced to the cartel leader—the insider who can point me to ecstasies I don’t yet know about. So we had a lovely conversation. I still remember it years later—not just the dialogue but even more his love of literature.

At one juncture, I asked my new friend a question. “But who is your favorite? You love all these writers, but who is the best living novelist?”

He didn’t need to think for long.

“Well, of course, there’s Cormac,” he said.

[Long pause] “But he’s in a class by himself. So let’s talk about some others.”

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

It was like I’d asked a Chicago Bulls fan to name the best basketball player of all time. The answer was so obvious that it was hardly worth discussing. You had to go down to number two or three on the list to get a real argument going.

My interlocutor couldn’t even be bothered to give the full name. Just Cormac—like Elvis or Oprah or Pele. A couple syllables were sufficient.

I knew many people who had the same view of Cormac McCarthy back then. And that was before he won the Pulitzer Prize for The Road, and the Coen brothers turned No Country for Old Men into a cult classic film. Even before those events, Cormac was larger than life, like a bleak Biblical prophet who somehow was writing novels in the current day.

Was he our best contemporary American novelist?

Cormac McCarthy’s first 5 novels were totally ignored. . . . Even Blood Merdian—now widely considered a modern classic of American fiction—got remaindered after only selling 1,883 copies.

I really don’t like rankings. I stopped ranking my best-of-year albums some time ago. When you get to the highest level of any art form, there are always several figures of historic importance to the idiom.

But Cormac McCarthy was clearly in that elite company. I might hem and haw, and offer three or four other names. But he belonged on the shortest of short lists.

Late last year, I learned that Cormac was planning to release his first new novel in 16 years. This caught my attention, as you can imagine. But even more striking—McCarthy was planning to release two books in late 2022.

These were interrelated novels, entitled The Passenger (published on Oct. 25) and Stella Maris (published on Dec. 6). As it turned out, these would be the final works released in McCarthy’s life—because he died two days ago at age 89.

He had reportedly been working on these books for four decades.

But it was surprising—at least to me—how little media attention this was getting. NPR, in a ho-hum write-up, explained that these books were “hard to categorize,” and described McCarthy fans as “rabid” and “fanatics.” You got the feeling they were reporting on some fringe cult that needed to be put in quarantine.

The New York Times kept using the word “portentous” in its review. That’s a word that has a positive and negative meaning—so take your pick. The Washington Post offered much the same, telling readers “prepare to be baffled.” If McCarthy’s final opus won any awards, I didn’t hear about it.

And many media outlets just ignored the book. But I guess that’s no shock—in the 16 years since McCarthy’s previous novel, most of the newspapers in America either fired their book editors or went out of business. In those periodicals, a new novel by a major author is like the proverbial tree falling in the forest—no matter how imposing all that wood pulp might be, nobody hears a thing.

Given this, I wasn’t even sure I should read the McCarthy books, except. . .

. . . Except that I kept hearing from individual readers how amazing these two novels were. These were people I trusted and their enthusiasm was off the charts.

So, finally, last month, I started reading The Passenger—and it was an extraordinary experience. So I followed up with Stella Maris, and it was just as brilliant, maybe better.

I thought I already had a good sense of this author’s range and capabilities. I knew he was a powerful psychological novelist. I knew he was a unsurpassed landscape novelist. I knew he had a formidable command of incident and character. But I had no idea that McCarthy was so skilled at writing dialogue—these works are filled with pages that could go straight into an Oscar-winning script. This is Tarantino or DeLillo level work.

And there many other unexpected joys in these two books. I don’t want to give out spoilers. But no matter how well you think you know Cormac McCarthy, you are still in for a jolt.

So why did the culture arbiters at legacy media give these books so little attention?

I could come up with many reasons:

A new book from an old dude (almost 90!) in New Mexico is not a cool, fashionable news story. Publishing, it seems, is also no country for old men.

McCarthy’s new books (like his previous ones) are brutal and unapologetic—and many readers will find them disturbing.

Cormac has always been a prickly recluse who doesn’t play the publicity game—and repeatedly refused to give interviews to the media outlets in question. So he drops to the bottom of their priority list.

He never networked with the influential people or glad-handed his way to the centers of power, and even now a price must be paid for this.

Etc.

This whole experience reminds me of why I rely so much on personal recommendations from trusted sources nowadays. These are simply more reliable—in books and music—than the resident pundits at the leading institutions. I wish that wasn’t the case, but it really is.

I could give other reasons for the puzzling media response to these brilliant books. But this is the place to explain that McCarthy, from the very start of his career, repeatedly faced indifference or hostility—and it lasted for decades.

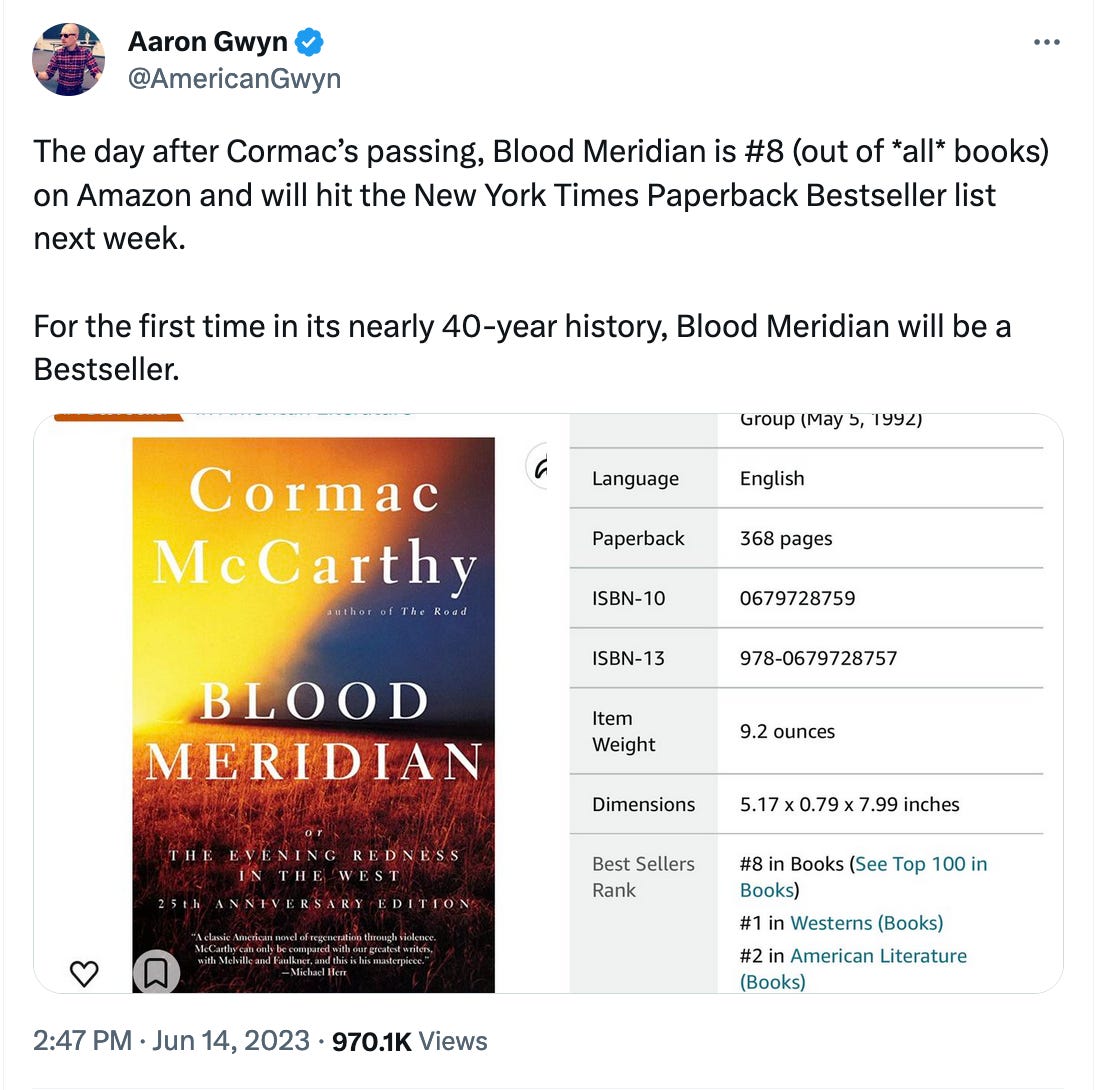

Cormac McCarthy’s first five novels were totally ignored by the culture media, and hence by readers who take such verdicts seriously. None of them sold more than 5,000 copies. Even Blood Merdian—now widely considered a modern classic of American fiction—got remaindered after only selling 1,883 copies. (That’s why first editions now sell for $10,000.)

Give credit to Cormac’s editor Albert Erskine, who worked with the novelist at Random House for more than 20 years. He continued to support McCarthy’s work despite poor sales. And who dared argue with Erskine, who had been editor for William Faulkner, Ralph Ellison, Eudora Welty, Robert Penn Warren, Malcolm Lowry, and other towering figures of American fiction?

They don’t make editors like Erskine anymore. Or perhaps it’s fairer to say the dominant publishing behemoths wouldn’t allow them to stick with an author for five books with lousy sales. Either McCarthy would be dropped from the roster, or the editor would get fired.

But Erskine backed McCarthy from the start, publishing his first novel The Orchard Keeper in 1965. It took more than twenty years for Cormac to get his due. But Erskine and Cormac persevered—and were finally rewarded.

Esteemed literary critic Harold Bloom would eventually name Blood Meridian as “the greatest single book since Faulkner's As I Lay Dying.” David Foster Wallace put it on a short list of the five most underappreciated modern American novels. When the New York Times polled famous authors to pick the greatest American novels of the previous quarter century, Blood Meridian finished in second place, surpassed only by Toni Morrison’s Beloved.

I admire Blood Meridian greatly, but before you buy a copy I need to read you the riot act. Cormac McCarthy has a dark and disturbing vision of the human condition. If you’ve seen the movie of No Country for Old Men, you already have gotten a taste of this. So you shouldn’t pick up any of his novels unless you’re ready for a tough ride in the saddle.

Even Harold Bloom, who also compared Blood Meridian to Moby Dick, admitted that he failed to finish the book the first two times he tried to read it—because the story is “so appalling.”

I would make a similar claim for McCarthy’s final works The Passenger and Stella Maris. In the latter book, the main character describes her worldview—which sounds similar to the author’s. I share it as a warning:

There was an ill-contained horror beneath the surface of the world and there always had been. That at the core of reality lies a deep and eternal demonium. All religions understand this. And it wasn’t going away. And that to imagine the grim eruptions of this century were in any way singular or exhaustive was simply a folly.

I’ll make a controversial statement at this point. Given the overall tone of society, we need brutal books that shake us up—but those are precisely the ones that publishers don’t want us to read.

We’re living in a paradoxical time. People and events are pushing us to the brink—and in the most ugly ways imaginable. But at the very same time, a pervasive daintiness and primness has taken over the world of books. It’s gotten so bad, that many books for kids are also marketed to grown-ups and vice versa—perhaps the lasting legacy of Harry Potter.

Sometimes I can’t even tell the difference. I start reading an award-winning new book, and ask myself: Is this targeted at me, or an early teen? Welcome to the Namby Pamby Era in fiction.

Just a few days ago, a novelist withdrew her book from publication—because it was set in Russia in the 1930s. This might hurt feelings (of Ukrainians, etc.). So the book got axed. For better or worse, that’s the literary culture in the year 2023. At this rate, we’ll soon have a new ending for War and Peace, with Napoleon returning from Moscow in triumph. Anything else would be indelicate.

This is why the culture wasn’t ready for Cormac McCarthy’s last works. And it’s also why we need them all the more.

And now Cormac gets the last laugh. Blood Meridian started climbing the sales rankings at Amazon immediately after the obituaries were published—get ready to see it on the bestseller list. And even before that, a film deal was announced.

McCarthy will not be denied. New readers are seeking him out, no matter what the institutional pundits have to say.

And there’s one thing I know for certain. These books will make quite an impression. In the midst of a delicate literary culture, something so harsh and harrowing stands out all the more. Who knows, maybe this will even put a dent in the dominant Namby Pamby aesthetic. If anyone could do that, it’s Cormac—who is still, even posthumously, in a class by himself.

I'm still haunted by 'The Road'

There's a stretch of I5, southern Oregon, where you go up and down, a series of crests, then down into the wooded valley. Each and ever time I crest, and start down into the next valley, I'm scanning for the smoke from small fires, and I get a chill. My wife get's tired of me re-telling the story every time. She doesn't know it, but I'm thinking about it every single ridge cresting. Powerful. Another great post Ted, Thanks.

I had read everything by McCarthy and just finished the last two a couple of months ago. A serious writer for serious readers. I am in awe of the magnificent, massive intelligence behind the writing. He may have been a recluse but he shared so much more humanity through his writing than through the "culture machine." He gave humanity to repugnant characters and asked us to look at them unflinchingly. As we should to ourselves.