The Deadliest Song in History

My Obsessive Search for the Music You Least Want to Hear

I’m told that streaming platforms have identified 5,071 different music genres—with listeners treated to everything from Witch House to Dark Cabaret, and much in-between. No matter what your mood or lifestyle concept, there’s a genre to set the tone. Just consider: If you wanted to try a different genre daily, it would take you almost 14 years to run the gamut—but, at the current pace, thousands of new genres would have appeared long before you were done.

Yet I am constantly surprised that, even amid this abundance, so many old genres have disappeared. Consider this list of songs included in ethnomusicologist Frances Densmore’s 1929 study Papago Music:

Song Before an Expedition to Obtain Salt

Song to Cure an Injury by a Horse

Song that Gave Women the Strength to Carry the Burden Basket

Song to Overcome Fear

Song to Put the Eagle to Sleep

Lamenting the Dead Eagles

Song to Make the Boy Invisible

Song of a Medicine Woman Upon Seeing that a Sick Person Will Die

Song When Restoring a Boy to Life

Anyone who digs deeply into the history and origins of music genres will find that song categories are much lesser things nowadays. They may promise entertainment or diversion, but certainly not invisibility or a return from the dead.

European culture once possessed songs of this awe-inspiring scope—in fact, there was an ancient Greek tradition, allegedly inspired by the mythic musician Orpheus, offering followers powerful hymns for navigating through the afterlife and other realms beyond normal human experience. To some extent, raves and other ecstatic dance parties in the current day preserve a remnant of these transcendental experiences—but don’t expect to access to them just by clicking on a Spotify playlist. Even the highest resolution music platform can only take you so far.

But I’m concerned with perhaps the most peculiar and troubling music genre of them all—a category of music I’d call deadly songs. To be specific, I am in search of the deadliest song of them all. This would be music that, from the first notes, told you bad news was on the way.

Here are some candidates I considered (but rejected) for that dubious honor:

The first example comes from the ancient Roman historian Tacitus, who described the songs of the Germans encountered on the battlefield during the late first century AD. Those who associate Germany with the highest levels of sophistication in composed music do well to read his account—the oldest description I’ve found of German music: “They also have the well-known kind of chant that they call baritus,” Tacitus explained. “What they particularly aim at is a harsh, intermittent roar; and they hold their shields in front of their mouths, so that the sound is amplified into a deeper crescendo by the reverberation.” This performance ensured that “they either terrify their foes or themselves become frightened.” (Not quite the Eroica; then again, maybe there is an ancestral connection—see below.)

Our next candidate for deadliest song is the formidable tradition of “singing the name” found in various Aboriginal communities in Australia. Waipuldanya, a member of the Alawa tribe in Australia’s Northern Territory, told journalist Douglas Lockwood that he almost died during childhood because his name was sung—and was only saved by relying on a practitioner with superior powers. To those who were skeptics, he explained: “I have seen the eyes of my tribal friends rolling in terror. I have seen them frothing at the mouth. I have watched them run amok and be struck dumb: all because they believed too readily when confronted with inexplicable phenomena.”

A third option comes from the Scottish tradition of sending bagpipers into combat to terrify the enemy. This practice has a long and illustrious history that continued well into the 20th century—during World War I, for example, around one thousand bagpipers were counted among the fatalities. The sound of the bagpipe was fearsome, because these musicians were known to lead the troops over the top into the enemy’s front lines. (A side benefit: If you were lost, you could identify the location of your regiment by the song played.) In a perhaps unique moment in music history, a British court ruled in 1746 that the bagpipes were officially an instrument of war—a classification that would not be rescinded for 250 years.

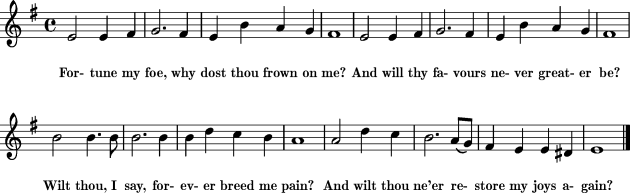

But my choice for the deadliest song of them all is none of these. Instead I want to give the honor to a 16th century Irish folk song that somehow got turned into the darkest soundscape of Elizabethan life. This melody spawned a whole genre of brutal and gloomy songs—with different lyrics used on various occasions, but almost always macabre ones relating to misery and death.

The song was known as “Fortune My Foe,” and it showed up at all the wrong times and places. Spectators would sing it at executions—it became so well known for this purpose that many simply called it “The Hanging Tune.” Ballad singers would use it to tell of murderous tales. Pipers would play it on their bloody military campaigns.

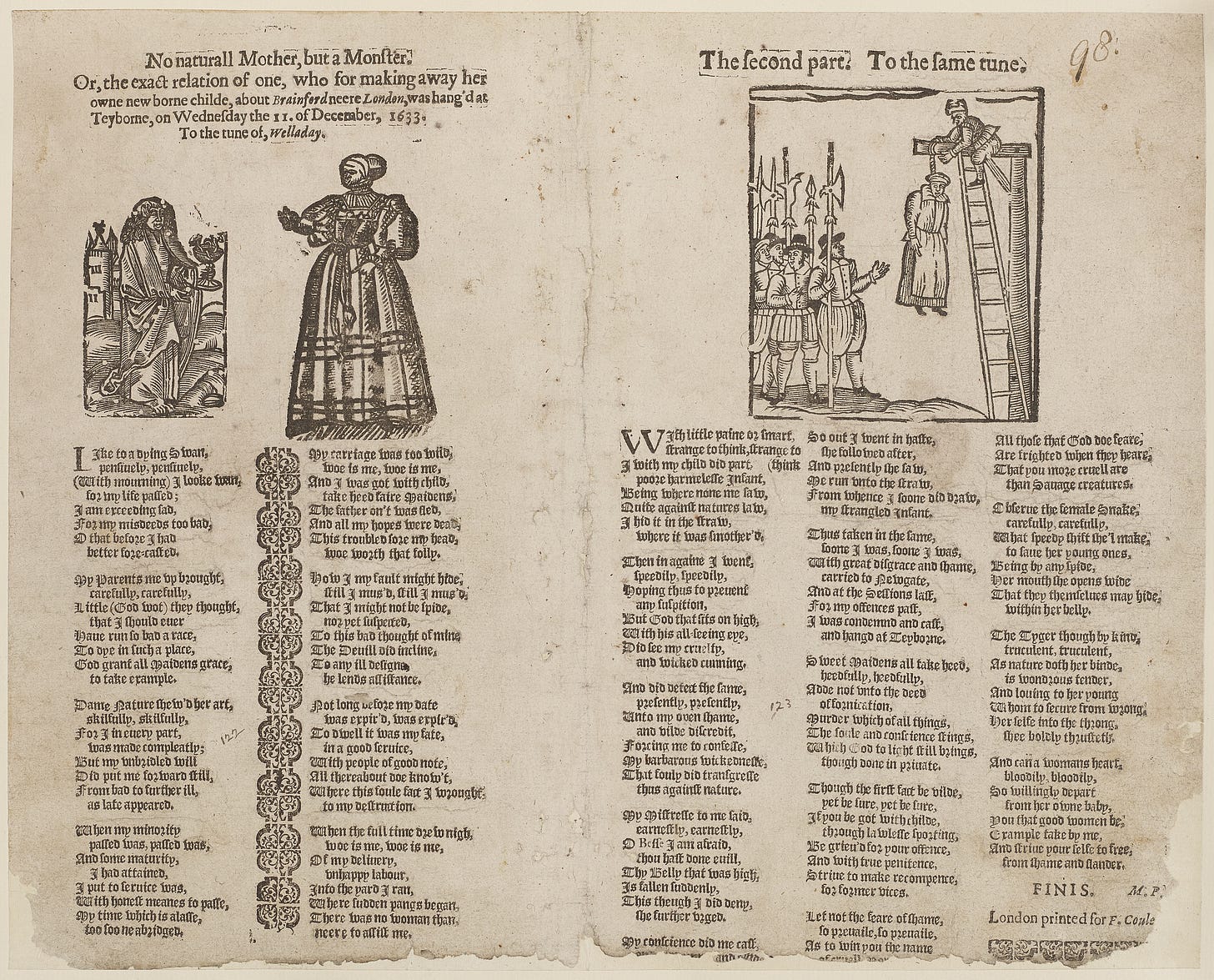

This melody also served as a platform for disseminating bad news of all sorts. When dark and gloomy tidings arrived in the village, it often came in the form of lyrics to this ominous melody. Even when that news was shared on the printed page in a broadside ballad, this convention was retained.

These breaking news stories spared no detail. A 1635 broadside ballad describing the execution of the Reeve brothers tells how the perfidious killers were hung by chains and their bodies left to decay, so passersby could gloat over this harsh justice. And to leave as little as possible to the imagination, an illustration was provided on the printed sheet next to the lyrics.

You could even make a case that these crude ballads were the original source of the visual meme. And just like those shared on the Internet nowadays, they were often accompanied by music. Strange as it seems, you can draw a direct connection between “Fortune My Foe” and the “Harlem Shake.”

Perhaps you find this idea vulgar and representing a tradition best forgotten, but even highbrow culture was shaped by “Fortune My Foe.” Shakespeare alludes to the song in The Merry Wives of Windsor, and his most violent play, Titus Andronicus, was based in part on a ballad sung to “Fortune My Foe.”

Yet this only gives the smallest hint of the flexibility of “Fortune My Foe,” which was also used for parodies, or adapted into much gentler contexts. Delicate instrumental arrangements were popular, for example a lute version by John Dowland.

I suspect that many musicologists are embarrassed by this dismal history. They prefer their songs to reside in concert halls, not at executions. But have we really evolved beyond such brutal uses of music? Consider the soundtracks of first-person shooter games or slasher films. These forms of entertainment are even more vividly realistic than the broadside ballads of yore—and they also rely heavily on accepted musical conventions to achieve their gory effects.

I once studied the soundtracks of the films with the greatest number of onscreen fatalities, and found that there are unmistakable ingredients that recur again and again in these contexts, many of them borrowed from 19th German orchestral and operatic music. So we have our own deadly music nowadays, we just don’t call it that.

If there’s a real discrepancy between different generations or eras, it’s certainly not because we are more virtuous or less inclined to music-accompanied violence. The gap is more one of contextualization. For the Elizabethans, this bloody music reflected the actuality of their society, and kept them informed on what was happening in their communities and among their neighbors. For us, the bloody music is consumed purely for enjoyment and thus is embedded in fantasy life and lifestyle definition. I’ll let you judge which of those two approaches is the most unsettling.

Your writings are fantastic Ted. Am teaching a class to at-risk kids on the Power of Music, and your material is perfect! Bravo.

What a great post!! I am delighted to discover your Culture Notes. And at the same time chagrined to find a music blog possibly more entertaining than my own. Drat!

https://themusicsalon.blogspot.com/