The Blue Collar Jobs of Philip Glass

I praise his work as a composer—but also as plumber, taxi driver, steel mill worker, and in other trades

Maybe a few stars get to boast, like Mick Jagger, that they’ll never be a beast of burden. The rest of us ask instead: ‘What’s the pay rate for beast work?’

That’s true for me. So I’ve done many unusual day gigs over the decades—blue collar, white collar, every kind of collar.

Only a few were genuine beast-of-burden jobs, but most made more demands than the typical 9-to-5 routine. And I also wanted to pursue my creative vocation on the side—so I learned to get by with very little sleep.

I never complained. This was just reality. You pay as you go. And I was glad to have a paycheck.

That’s true for many of you, too. I know that for a fact.

You feel a calling in music or some other creative pursuit, but don’t have a trust fund or family members with deep pockets. You don’t want to sacrifice your hopes and dreams—but hopes and dreams rarely pay well by the hour. So we find other ways to survive

It isn’t always pretty.

If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

I respect artists who make these sacrifices. That’s one reason I admire composer Philip Glass—not just for his musical works, but also for the many other kinds of work he did.

Like me, he kept doing day gigs into his forties. Then he finally earned enough from composing to focus entirely on music.

“I never considered academic or conservatory work,” he later recalled in his autobiography Words Without Music.

“Of course, I was never offered a job anyway.” The first time Philip Glass got an inquiry—not even an offer, just a conversation—about teaching, he was 72 years old.

That’s more common than you might think. Many of my cultural heroes were ignored by academia, or found some entry point only to get denied tenure or face other forms of hostility.

But Philip Glass deserved better. He had an amazing track record—starting when he entered the University of Chicago at just age fifteen. (He did so well on the entrance exam that they let him in without a high school diploma.) Then came time at Juilliard. and overseas as a protégé of Nadia Boulanger, teacher to the leading composers of the century, who predicted that this student would achieve greatness in music.

He was so poor, that Boulanger volunteered to teach him for free.

But Glass could make good money in blue collar jobs back in the US. And he taught himself many trades over the years.

His family was opposed to his music career. They feared he would turn out like Uncle Harry, a dental school dropout who worked as a drummer in vaudeville and Borscht Belt hotels. So how did Glass pay his way at Juilliard?

Glass, like the musicians mocked in the song “On Broadway,” took a Greyhound bus back home to Baltimore. But he didn’t stay there for long—just five months.

He made enough money in that time to pay for his New York education. But that’s only because this intrepid 20-year-old aspiring composer somehow convinced Bethlehem Steel to give him a job at their plant in Sparrows Point, Maryland.

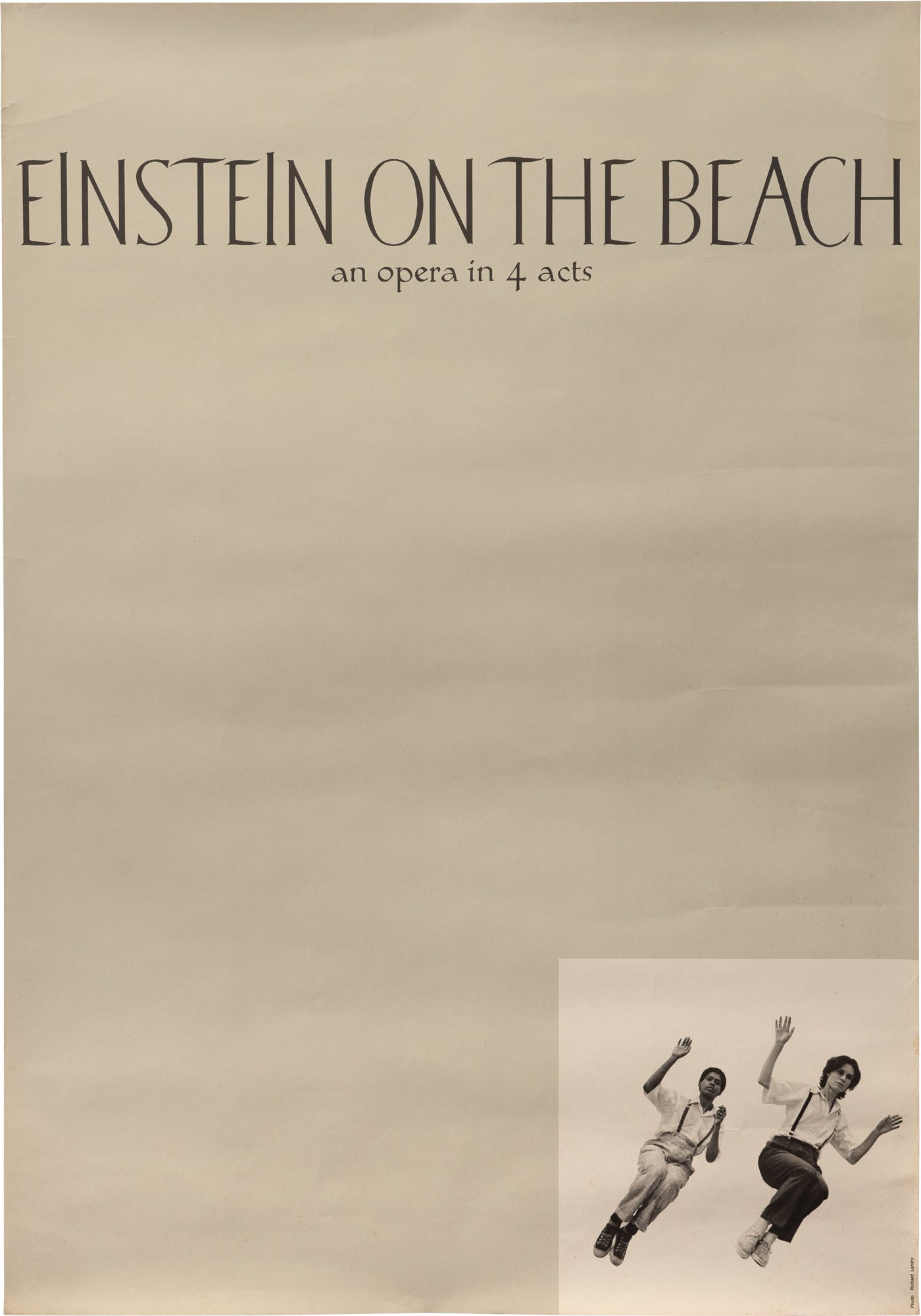

Here the future composer of Einstein on the Beach operated a crane. During breaks he devoured all of Herman Hesse’s novels. Just imagine reading Siddhartha or The Glass Bead Game at a steel mill—but that’s Philip Glass for you.

He saved up, and a few months later Glass had enough money to return to New York.

That served as the pattern for more than two decades. He kept getting better as a composer, but still took demanding day gigs.

So Glass was delighted when, on his return from his Paris days with Boulanger, a friend was waiting for him at the pier in New York—who told him:

“Don’t worry. I’ve got your truck.”

And just like that, Philip Glass was in the business of moving furniture. “We didn’t have uniforms, much less gloves. We didn’t even have insurance.” But he advertised in the Village Voice—under the names Prime Mover or Chelsea Light Moving—and got regular work.

He got so much work that the truck eventually fell apart. After that, Glass persisted—renting trucks by the day when he had a moving job.

In his autobiography, Glass explains:

“I could manage quite well working as few as twenty to twenty-five hours a week—in other words, three full days or five half days. Even after I returned from Paris or India in the late 1960s and well into the 1970s, I could take care of my family by working no more than three or four days a week.”

Like many artists, Glass took advantage of the revitalization of Soho, when industrial lofts were converted into residences and creative spaces. But Glass benefited in a different way from other musicians—he actually built artist lofts.

At first, he got jobs installing walls with sheet rock. “This was heavy work,” he recalls.

Glass later claimed that he “gained an extra twenty years of life” because he did demanding physical work in his 20s and 30s, not partying and getting stoned.

Then he started taking on plumbing jobs—even though he had no experience in the field. When he had an installation job, he got advice from the guys who worked at the plumbing supply store on Eighth Avenue near 18th.

He simply did what they told him—and gradually learned the plumbing trade. He started with sinks and toilets, and worked up to hot water heaters and interior pipes. For three years, he worked for a plumbing company on Prince Street off of West Broadway.

This sometimes led to strange encounters. Glass shared this story in a 2001 interview:

“I had gone to install a dishwasher in a loft in SoHo. While working, I suddenly heard a noise and looked up to find Robert Hughes, the art critic of Time magazine, staring at me in disbelief. ‘But you’re Philip Glass! What are you doing here?’ It was obvious that I was installing his dishwasher and I told him I would soon be finished. ‘But you are an artist,’ he protested. I explained that I was an artist but that I was sometimes a plumber as well and that he should go away and let me finish.”

Glass made creative use of these experiences too. When he later took a job as studio assistant to abstract sculptor Richard Serra, Glass convinced the artist to start using lead for his works.

Glass knew about this from his plumbing jobs, and even brought Serra down to that same supply store on Eighth Avenue. There he showed Serra all the materials and tools—and the artist immediately started working with lead.

You might think that Glass could have made a full-time living in music by this time. But that wasn’t the case. When he performed with his ensemble on the road, he typically lost money. He needed to work 3-4 weeks just to pay off the costs of each tour.

“I never got any money from grants,” Glass adds. He came close when the New York State Council on the Arts awarded him $3,000. “But when they found out I was working, they asked for it back, so I never applied for any grants after that.”

In the mid-1970s, Glass decided he needed work that was less physically draining, and with more flexible hours. So he became a taxi driver. By curious coincidence, this is the same period when Robert De Niro did the same thing in preparation for his role in the film Taxi Driver (1976).

I like to imagine Glass and De Niro encountering each other on the job. Maybe that happened at the Dover Garage in Greenwich Village where Glass picked up his taxi in the late afternoon. Then he would typically take fares until well after midnight.

After returning home, usually around 1:30 AM, Glass would stay up the rest of the night, working on his compositions. Much of Einstein on the Beach was written this way. Then, in the morning, he would take his children to school, and only then finally get some sleep.

“Driving a cab was never a problem for me,” he later recalled. “I liked driving in New York and got to know the city very well.” On a typical night, he would drive a hundred miles or more.

But this was a dangerous time to drive a taxi in New York. “Drivers were regularly getting killed in their cabs,” he notes. “I would say five to ten cabbies got killed every year.”

“I was almost killed a couple times,” he admits. His closest call came when four assailants attacked the car late one night on a deserted street. Glass was dropping off a passenger, when they struck—two at the back doors and two at the front doors of his taxi.

The front doors were fortunately locked, but the attackers opened the back doors. Before they could enter, however, Glass floored the gas pedal.

“I was a block away within seconds. I don’t doubt if they had gotten me—if they had opened the door and pulled me out—that I would’ve been dead. That was what was going on then. Some people thought cabs were banks on wheels.”

Glass’s career as a taxi driver ended in 1978, when he got a commission from the Netherlands Opera. The resulting work, Satyagraha, was inspired by the life of Mahatma Gandhi—and it takes its name from Gandhi’s concept of non-violence.

That commission coincidentally allowed Glass to avoid the violence he was potentially facing in his side gig on the streets of New York.

After that, Glass was a full-time composer. He was 42 years old when he walked away from these day (and late night) gigs.

Some people will tell you that all this is irrelevant to Philip Glass’s musical work, but I disagree.

Sometimes I think I can hear the rhythms and textures of his workaday life in the music.

But even more, I respect the commitment and resolve Philip Glass demonstrated during more than two decades of blue collar jobs. Others would have given up. Or maybe they would have found some scam or subterfuge—scheming to get others to pay their bills and cover their costs.

Many creative people would have complained how they deserved better, and a bitter resentment might have entered into their music—that often happens because art usually reveals the artist.

But Philip Glass isn’t like that. I could devote another essay to his spiritual disciplines, practiced over a period of more than sixty years and encompassing hatha yoga, Tibetan Buddhism, Taoism, and the Toltec tradition of Mexico. Close to a third of his autobiography deals with these pursuits.

And there were other benefits to this peculiar approach to a career in the arts. Glass later claimed that he “gained an extra twenty years of life” because he did demanding physical work in his 20s and 30s, not partying and getting stoned.

He is now 87 years old, and still active as a composer. Here’s some music he recorded at his home studio during the COVID lockdown.

In other words, these jobs—even the beast-of-burden ones—made him stronger in every way.

So I celebrate Philip Glass the composer, but also as a role model in so many other ways. He’s not just the hardest working man in minimalism, but maybe the most versatile in self-reinvention of any major composer in the Western canon.

Glass did all this by taking on the toughest jobs in the toughest city on the planet. And instead of letting it drain him, he turned everything into a source of self-reliance, energy, and confidence in his life.

Maybe that’s something we all can learn from, and not just musicians.

One of the underrated benefits of having a blue collar job is that the people you work with, when they find out you have any kind of smarts or talent (and if you are doing a good job working with them), will often encourage you to go to school or perform or whatever it is you need to do to use those abilities. And hard, repetitive work gives you plenty of time to think.

Charles Mingus worked in the post office, Albert Einstein was clerk in a patent office. You do what needs to be done in order to pay the rent.