Stupidity: A Reading List

You get smarter by studying foolishness—so here's how I'd teach a 12-week course on stupidity

Several people have asked me to provide a reading list in the humanities.

That sounds like a good idea—until I actually begin. There are so many books and such little time.

So I worry I’ll end up like W.H. Auden, who expected his students to read six thousand pages in a single semester.

Hannah Arendt’s syllabus for her 1974 class on Thinking isn’t much easier.

Okay, she lets students skip Kant’s The Critique of Pure Reason except for an extract, and issues a merciful governor’s reprieve on (her lover) Heidegger’s Being and Time. But she serves up ample doses of Hegel, Wittgenstein, Plato, Merleau-Ponty, and Aristotle.

No college class in the US would make such demands today:

I’ve read most of these books, and won’t dispute the benefits. But it took me decades to gain a mastery of the canonic texts—I’m a slow reader. Finally in my early 40s, I started to feel a command of the tradition, and had some confidence in how I applied it in my own life.

But that was a huge project—maybe the most ambitious I’ve ever tackled.

So I’m not going to provide some long, imposing list of great books. That’s not education or erudition—it’s cruelty.

Instead I will offer a series of focused reading lists.

Today I will start with the most important one of all. I’m sharing my reading list on stupidity.

Why are you looking at me like that? Do you think I’m joking?

Not in the least.

The single best thing you can learn in college is stupidity. Currently it’s just an (extremely popular) extracurricular. But they really should turn it into a major—Stupidity Studies.

The fastest way to get smart is to avoid the pitfalls of the stupid. But you need to learn them first.

Today I’ll step forward as your esteemed Professor of Stupidity. (Can I put that on my LinkedIn profile?) Below is my stupid reading list—designed for a twelve week course.

It may not be as daunting as Auden’s and Arendt’s list. But even stupidity will still take you a few months to learn. There are no shortcuts on the fool’s road.

I also include a final exam in stupidity. That should be easy to pass, no?

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Stupidity: My Reading List for a 12-Week Course (and a Final Exam)

By Ted Gioia

“Who knows if a dense, aggressive stupidity might not provoke illumination.”

E.M. Cioran

“Stupid is as stupid does.”

Forrest Gump

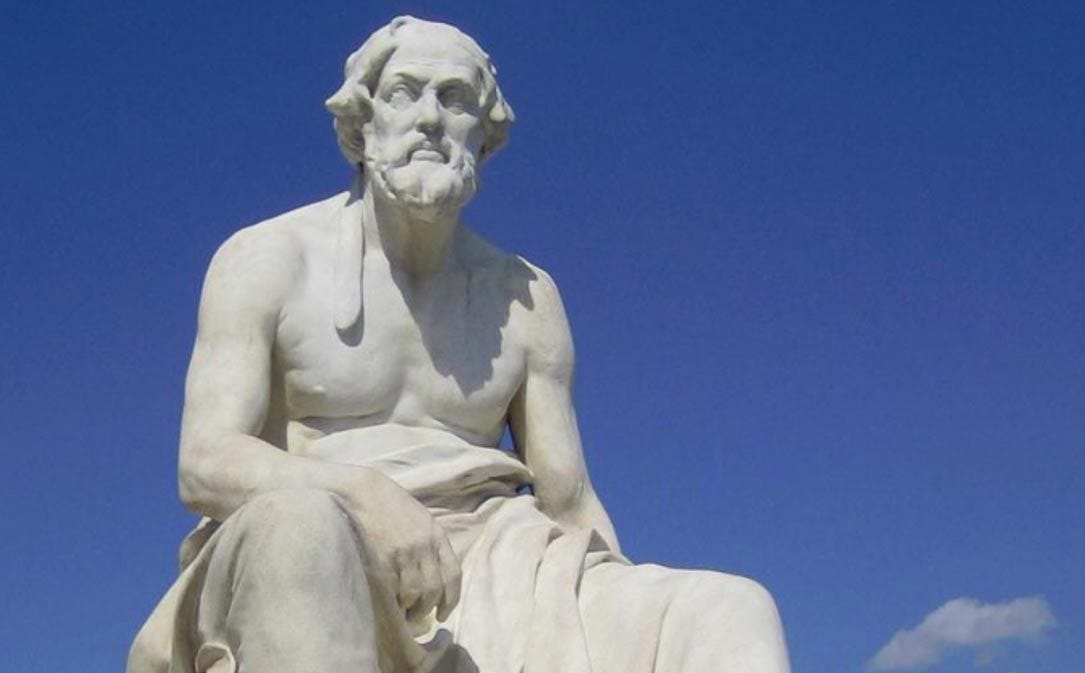

Week 1: Thucydides: History of the Peloponnesian War (Circa 400 BC)

This book is absolutely the place to start—and it marks an important moment in human culture. For the first time in the Western world, a historian turned to his own society and said: “This is stupid.”

So Thucydides studied it. He diagnosed its causes and effects. He laid it out for others to learn from.

His subject was the war between Athens and Sparta—and Thucydides was a participant. He watched as his native Athens laid the foundation for its own defeat through hubris and overreaching. Never before had a historian dealt with such brutal, unflinching honesty when facing the shortcomings of his own generation.

We should all learn from this.

Week 2: Tacitus: The Annals (Circa 100 AD)

There are many eye-opening books on Roman stupidity—so many that I have to leave most of them off my list. There just isn’t enough room to cover the entire history of Roman decadence and fatuousness.

I will only feature two short books here, by Tacitus and Procopius (see below). But you would also do well to read Suetonius, Martial, Apuleius, Juvenal, and others to get a larger picture of Imperial idiocy.

Tacitus is less gossipy than these others, but his sober realism makes his dissection of Roman corruption all the more useful. He understands what good governance looks like, but is cursed to live in a time where stupidity, crassness, and self-serving behavior are in ascendancy.

Does that sound familiar?

The fact that many of his observations are relevant today makes The Annals all the more painful—and useful—to read. Every politician should be forced to study it from cover to cover.

Of course they won’t, but you can.

Week 3: Procopius: The Secret History (550 AD)

Four hundred years have elapsed since Tacitus, but the Roman empire—now morphed into the Byzantine Empire—hasn’t gotten any smarter in the interim.

Procopius of Caesarea is our guide to this new phase in Imperial stupidity—because he sees Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora up close and personal.

What he knows is dangerous to tell. You can’t expose the stupidity of rulers without paying a heavy price. So Procopius writes in secrecy, just for his own satisfaction—and the benefit of posterity.

The Secret History was so secret that this book was unknown until the Renaissance. A manuscript was discovered in the Vatican Library and published in 1623. And what an amazing book it is. I only wish that insiders would write with such bravery and honesty in our own times.

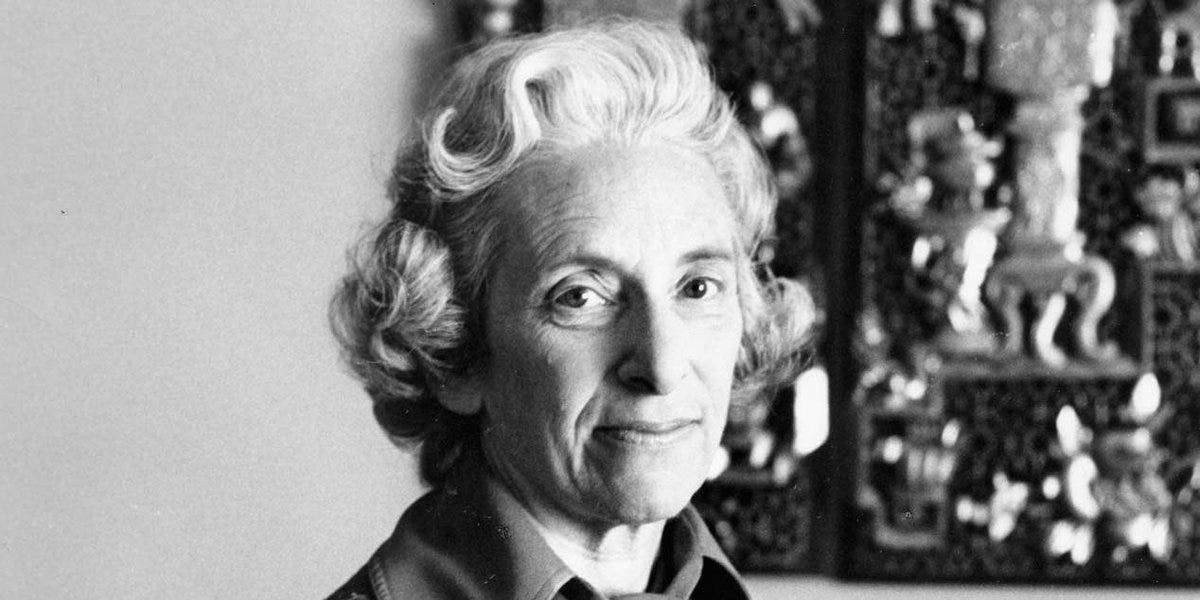

Week 4: Barbara Tuchman: The March of Folly (1984)

Barbara Tuchman never earned a graduate degree in history, but that didn’t prevent her from winning a Pulitzer Prize (twice!) and teaching at Harvard. She published the best modern guide to stupidity, The March of Folly, in 1984—where she covers everything from Ancient Greece to the Vietnam War.

Few scholars have ever put more faith in the notion that history has painful lessons to teach, and historians carry a responsibility to impart them. Some believe she was too harsh on the US foreign policy establishment in her critique, but subsequent events show them repeating the very same errors Tuchman highlights—with similarly disastrous results.

Week 5: Erasmus: In Praise of Folly (1511)

We cannot convict the foolish without giving them a chance to respond. For that we must turn to Erasmus of Rotterdam, who delivered this brilliant defense of folly.

He almost convinces us that stupidity is superior to wisdom. Foolishness, he claims, is the path to a happy life, and maybe even a saintly life.

This may have been where Shakespeare got his idea for fools who say wise things—a recurring trope in his plays. When Dostoevsky wrote The Idiot, he pushed this notion even further, insisting that any genuinely good and benevolent person must appear a fool in the eyes of the world.

The same concept underlies the film (and book) Forrest Gump—in fact, this Hollywood hit comes straight out of the Erasmian playbook.

Erasmus seems like a joke—like Gump and Dostoevsky’s Prince Myshkin. But you do well to take them seriously.

Week 6: Charles Mackay: Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowd (1841)

I plan to write more in the future about crowd manias—a subject that greatly interests me. Mackay is our single best source on the subject. Even if you don’t know his name, you may have heard the stories he shares—for example, the great tulip bulb mania of the 1630s, for which Mackay is the most frequently cited source.

There’s a reason why many leading investors study this book, which taught me things about finance I never learned in business school. But this work also helps you understand so many other matters, from pop culture to fashion to social media.

Weeks 7 & 8: Gustave Flaubert: Madame Bovary (1856) and Bouvard et Pécuchet (1881)

No novelist was more savage than Flaubert in exposing the lies that vain and fatuous people tell themselves—so he gets two books on our reading list. Madame Bovary is the best known of these, and stands out as the supreme literary case study in self-serving human vanity. Bouvard et Pécuchet, a satirical tale of two foolish friends, is less well known, but a classic in its own right.

Flaubert’s critique is all the more incisive because he rarely passes judgment, and lets his characters convict themselves via their own overreaching. If you have lived much in the world, this will strike you as painfully realistic.

Special Event for Week 8:

A screening of the film Idiocracy. Attendance is mandatory.

Week 9: Samuel Butler: The Way of All Flesh (1903)

This novel about stupid parenting occasionally shows up on lists of the greatest books of the century, but very few people read it. That’s a shame because this novel is so forward-looking. You might even claim that Butler invented the concept of the generation gap.

Nowadays, parents are often mocked in books, movies, and TV shows. It’s almost a cliché: the protagonist somehow rises above the imbecilities imposed by the older generation. But brutal criticism of parents was almost taboo in fiction until Samuel Butler delivered a fierce critique of what fathers can do to sons in this brave book.

Here is George Orwell’s assessment:

"It gives an honest picture of the relationship between father and son, and it could do that because Butler was a truly independent observer, and above all because he was courageous. He would say things that other people knew but didn't dare to say. And finally there was his clear, simple, straightforward way of writing, never using a long word where a short one will do."

Week 10: Svetlana Alexievich: Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets (2013)

The winner of the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature, Svetlana Alexievich, is hardly a household name, especially when compared with the 2016 honoree Bob Dylan. And she earned the prize as a non-fiction writer, a great rarity. But she eminently deserves her rise to global literary fame for a series of works that are (in the words of the judges) “a monument to suffering and courage in our time.”

Any syllabus of human vanity and overreaching must deal with the plight of the Soviet Union, and Alexievich dealt with this subject in books on Chernobyl and the Afghanistan war. But the place to star is Secondhand Time, an oral history covering the collapse of the USSR, and the challenges of citizens struggling to adapt to the aftermath.

If you think it’s easier to live in truth rather than lies, this book will force you to reconsider. Here’s a passage:

“More often, people were irritated with freedom. ‘I buy three newspapers and each one of them has its own version of the truth. Where’s the real truth? You used to be able to get up in the morning, read Pravda, and know all you needed to know, understand everything you needed to understand.’…Everyone thought of themselves as a victim, never a willing accomplice.

Week 11: Umberto Eco: Foucault’s Pendulum (1988)

Eco is a brilliant, devious writer. In this novel, three friends find themselves increasingly obsessed by a wide range of conspiracy theories. Everything is here: secret societies, the Knights Templar, Freemasons, Opus Dei, you name it.

These unhinged researchers somehow manage to pull all their crazy ideas together into a unified theory of conspiracy. Their exploits are both amusing and alarming, proving the great lengths people will go along the highway of half-baked ideas.

This novel, written before the rise of the Internet, is even more relevant in a digital culture, where conspiracy theories have more influence than ever.

For Extra Credit:

You can write a brief paper on one of these additional books:

Growing Up Absurd by Paul Goodman

Mumbo Jumbo by Ishmael Reed

The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Ship of Fools by Katherine Anne Porter

The Peter Principle by Laurence J. Peter

A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

Week 12: A Final Exam in Stupidity

Answer three of these questions—drawing on our readings, your core values, and your personal experiences.

In the digital age, we have access to all the world’s wisdom at our fingertips and super smart bots to answer all our questions. Will this eliminate stupidity? Or make it worse?

Who is stupider—an individual or a group? Analyze and compare both. Make sure to provide examples.

Why is the Tree of Knowledge considered dangerous in Western Judeo-Christian tradition? Isn’t knowledge superior to ignorance?

How could we lessen the impact of stupidity on our lives? Or should we?

Sociologist Max Weber claimed that bureaucracies are efficient because they decide everything by clear and well considered rules. Yet people constantly complain that bureaucracies are stupid. How is this contradiction possible?

“The best way to expose stupidity is through comedy—not journalism or history or even philosophy. Laughter is our most powerful remedy.” Agree or disagree?

Do universities lessen the amount of stupidity in the world? Or do they increase it?

What political institutions are most valuable in resisting stupidity?

Is the world getting smarter or stupider? How will this play out over the next 50 years?

That’s our reading list in stupidity. Get smart, and check out a few of the titles.

I may publish other focused reading lists in the future. If you have suggestions for topics, tell me in the comments.

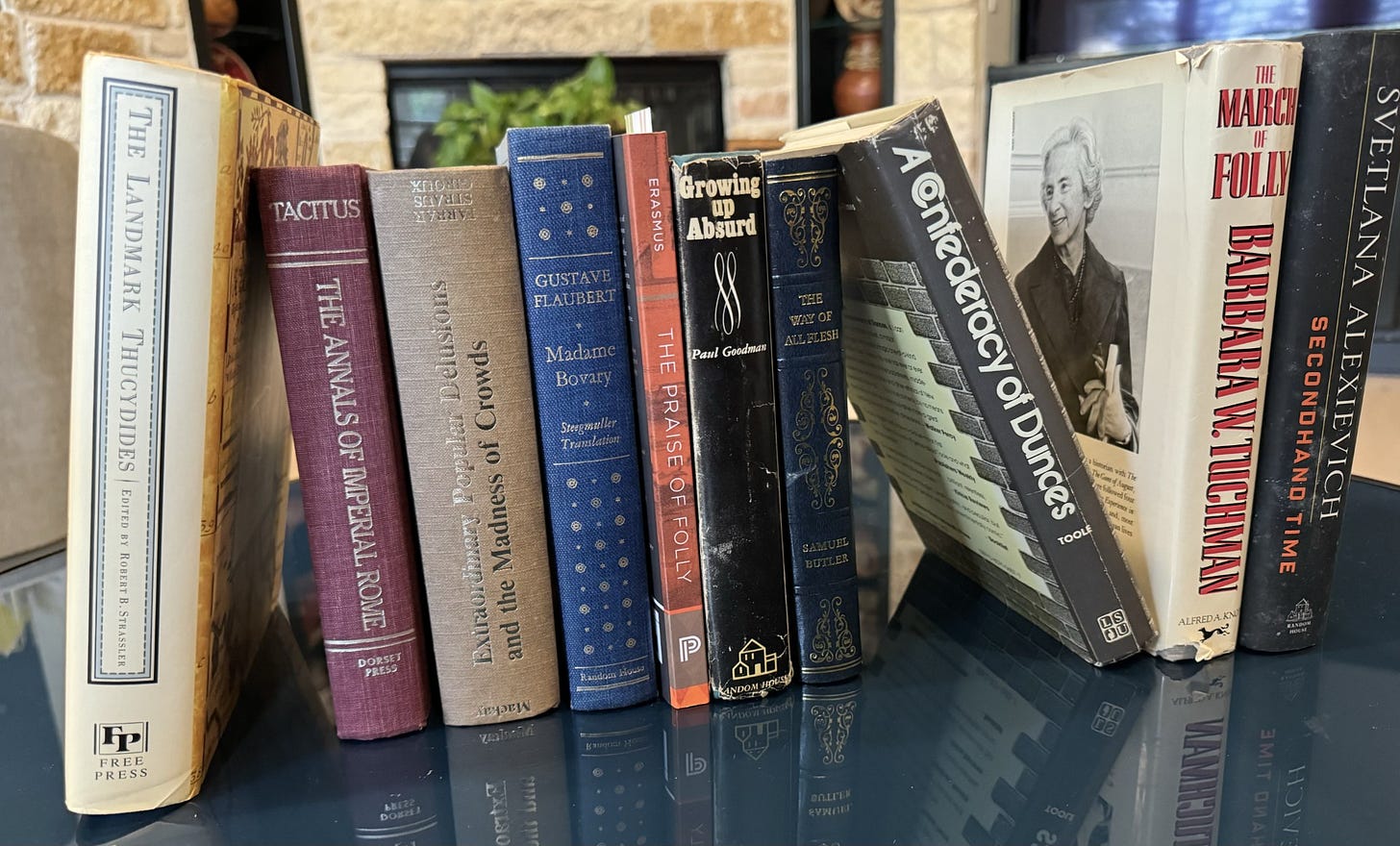

I love this, but...I've read Thucydides. Allowing one week for that book suggests you have incurable optimism about people's reading abilities and speeds 😂. I think it took me about 6 months. And may I recommend The Landmark Thucydides if one is going to make the attempt? The maps and annotations make this fascinating work so much more accessible...

Ignorance in general does not bother me, because it is all around me.

What does bother me is when someone is ignorant and proud of it!