My Lifetime Reading Plan

I share some private details of how I educated myself through books

I want to tell you how I gave myself an education by reading books. I’m going to do this in two installments.

In part one, I’ll share the techniques that worked for me. In part two, I’ll tell you about the mistakes I made—and what I’d change if I was doing this all over again.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

But I need to issue a warning upfront.

Here’s the warning: I am not recommending these tips and techniques for anybody. What I did was extreme, and driven by an intense desire to expand my mind and broaden my understanding of the world. I went beyond what was reasonable—almost the way a high performance athlete trains for some ultra-competitive event.

That’s why I’ve never discussed this publicly or written about it before—although this reading strategy has been a major part of my life for decades.

You could even say my lifetime reading plan was an extreme sport—only without the physical exertion. I stayed in my comfy chair instead.

Okay, that sounds absurd. But in terms of discipline, consistency, and mental focus, the comparison is apt. What I did with books was like karate or mountain-climbing for the soul and mind.

So I share these techniques only because people are curious about such things, and not because I want or expect others to climb the same mountain. However, I am aware that a few of you are pursuing a similar self-education program and some, like me, have been doing this for decades with significant results. For those folks, these tips may have some practical value.

And a tiny number of you might actually join our ranks after hearing my story. That would make happy if it happened.

HOW TED BECAME WELL READ

First, I should explain my motivations. To some they will seem obvious, while others will consider them hopelessly naïve.

For example, back when I was a teenager I decided I wanted to possess genuine wisdom. You can laugh at that if you want. The very word wisdom seems tainted nowadays. Some will tell you wisdom is a sham, others will dismiss it as something only charlatans or cult members promise. Those of a postmodernist mindset will insist that it doesn’t even exist.

But that was my goal: the pursuit of wisdom.

And along with it, I wanted to develop a meaningful philosophy of life. That seemed urgently important to me as a teenager. It still does today. I wanted to take the high road, with the right values, and pursue the best goals. I wanted to appreciate the world around me more deeply, more richly—and not just the world today, but also the world in different times and places, as seen by the best and the brightest.

Some people will tell you that this is elitist. But I have the exact opposite opinion. For a working class kid like me, this was my way of overcoming elitism. Some elites even tried to steer me away from this project—as not appropriate for somebody from my neighborhood and background.

I felt that this was patronizing in the extreme. In any event, I was determined to puruse this path of wisdom even if others tried to discourage me.

I felt that my best way to do all this was through books.

In fact, that was the only way. Now that may surprise you, because most people think that learning of this sort takes place at school. This leads me to my first tip or technique:

WHAT YOU LEARN IN CLASSROOMS IS IRRELEVANT, AND SOMETIMES EVEN WORTHLESS—YOU MUST TAKE RESPONSIBILITY FOR YOUR OWN EDUCATION

I got the best formal education that money could buy—or in my case, student loans, because my family didn’t have the cash to pay for my education. I eventually earned several degrees that hang on my wall, each from an impressive institution.

But more than 90% of my education came on my own.

That’s almost absurdly true in my case. I made my name as a music historian and jazz writer, but none of my degrees are in music. I never took a class in jazz in my entire life—or even a single lesson. I would have done it if I could, but I never went to a school or college that taught jazz.

I had to learn on my own. That’s a useful skill—teaching yourself. Maybe the most useful.

But let me go back to my lifetime reading plan. Only a tiny part of this happened at college, although I did benefit from some outstanding professors. But here’s the key fact: my best professors were more valuable as role models than for the books they assigned. They gave me a sense of the kind of life and worldview I wanted to cultivate for myself.

But that’s true only of the very best professors. It’s a tiny number. But they stand out—they almost radiate a kind of wholeness and depth. (I’ll talk more about that radiance below.) They teach classes, but they really teach by example.

And they also learned from books. So they make you want to read them too.

I SPENT A LOT OF TIME READING—I MEAN ORCA-SIZED TIME BLOCKS

When I was in high school, I got up at 5:30 AM so I could read a long time before going to my first class. Over the course of my life, my daily schedule starts with reading and ends with reading—and there are blocks of reading during the day.

There have been times in my life when I had to work demanding jobs, with late hours and constant deadlines. But I always found time to read for an hour or so before starting work in the morning. This frequently cut into my sleep or forced me to make other sacrifices.

I always begin the day with a book. I read at lunch. I read at dinner (until I got married). I read at night before going to sleep. Then I start the cycle again the next day.

I remember times when I was so exhausted by the demands put on me that I felt I had reached some limit of psychological and physical endurance. But I still set the alarm clock an hour or so earlier than necessary so I could have my reading time.

Giving up on that would have been like abandoning my own core principles, or selling out to the system.

But if this sounds like a burden, I must disagree.

The reading is like meditation to me. It refreshes me. It centers me. It energizes me. When I sit down each morning with three items next to me—a cup of coffee, a glass of orange juice, and a book—I’m doing something that’s total joy.

I READ FOR MIND-EXPANSION NOT ENTERTAINMENT, AND SEEK OUT CHALLENGING BOOKS

When I started my first job with the Boston Consulting Group, right out of business school, I was reading Sartre’s Being and Nothingness in the mornings before going to the office. The book was almost poetic in its obtuseness, but it was perfect for my needs—I wanted something that took me out of my day-to-day concerns, and nothing does the trick quite like 800 dense pages of French existentialism.

This has always been my pattern. If books were my drug, I always was taking the big intense dose that offered the greatest out-of-body experience. You rarely find those kinds of books on the bestseller list.

If you’re serious about an education, you should read at least one or two long, challenging books each year. When other people pick up light beach reading for the summer, you ought to grab Thucydides or Gibbon or Musil or Woolf or Schopenhauer.

When I was 18, I tackled War and Peace. When I was 19, I did Don Quixote. The next year, I read The Brothers Karamazov, and after that it was Moby Dick and The Tale of Genji and The Magic Mountain. And I’ve kept doing this for decades.

The cumulative impact of this is life-changing.

IT’S OKAY TO READ SLOWLY

I tell myself that, because I am not a fast reader.

I can do speed reading, if it’s absolutely necessary—but I find it painful and exhausting. My natural reading pace is languid, almost lethargic.

Even more to the point, the books I read must be savored and slowly digested. Proust is one of my favorite authors, but I could only handle his ultra-dense writing in small doses. So I read through his 2,000-page novel at the pace of seven pages per day. I started when I was a teenager, and got to the final page shortly before my 30th birthday.

Of course, I read many other things during that period, but I always came back to his massive book—taking it slowly, thoughtfully, in the way it deserved.

For many years, I felt that my slow reading was holding me back. I would be wiser, I would be smarter, I told myself, if I could just read faster. I often keep going back over the same sentences again and again, trying to decipher their inner meaning. This slows me down to a tortoise’s pace—and it’s frustrating.

But now I believe slowness was a benefit. My learning was deeper and more mind-expanding because I didn’t rush it.

By the way, I did the same thing when I learned jazz piano. I spent months learning things that could have been mastered in days. But by the time I was done, I had internalized my learning at a deep level.

Life is not a race. The journey is its own reward. If we could make the trip instantaneously—like they do with those teleporters in Star Trek—it wouldn’t be worth anything.

READING OUT LOUD IS GREAT

I some times slowed myself down further by reading aloud. Some works are better savored this way, because of the music of the language. For poetry, hearing the sounds is essential. But I even did this for some prose works. For example, I’ve read Finnegans Wake by Joyce and the King James Version of the Bible out loud from cover to cover.

Now you’re starting to see why I said upfront that I’m not recommending that ANYBODY imitate me. What fool reads all of Finnegans Wake out loud?

I am that fool.

I KEEP TRACK OF MY READING

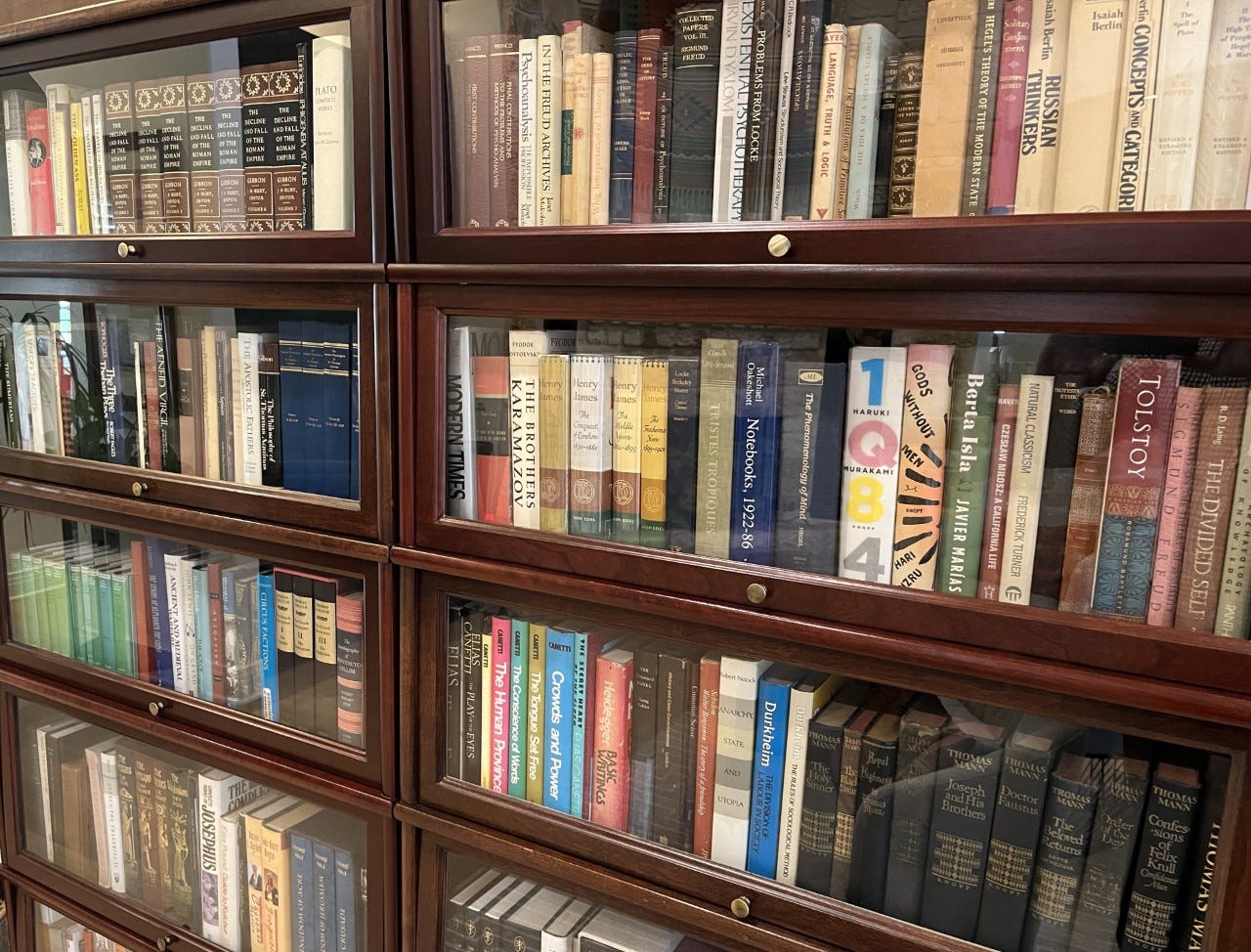

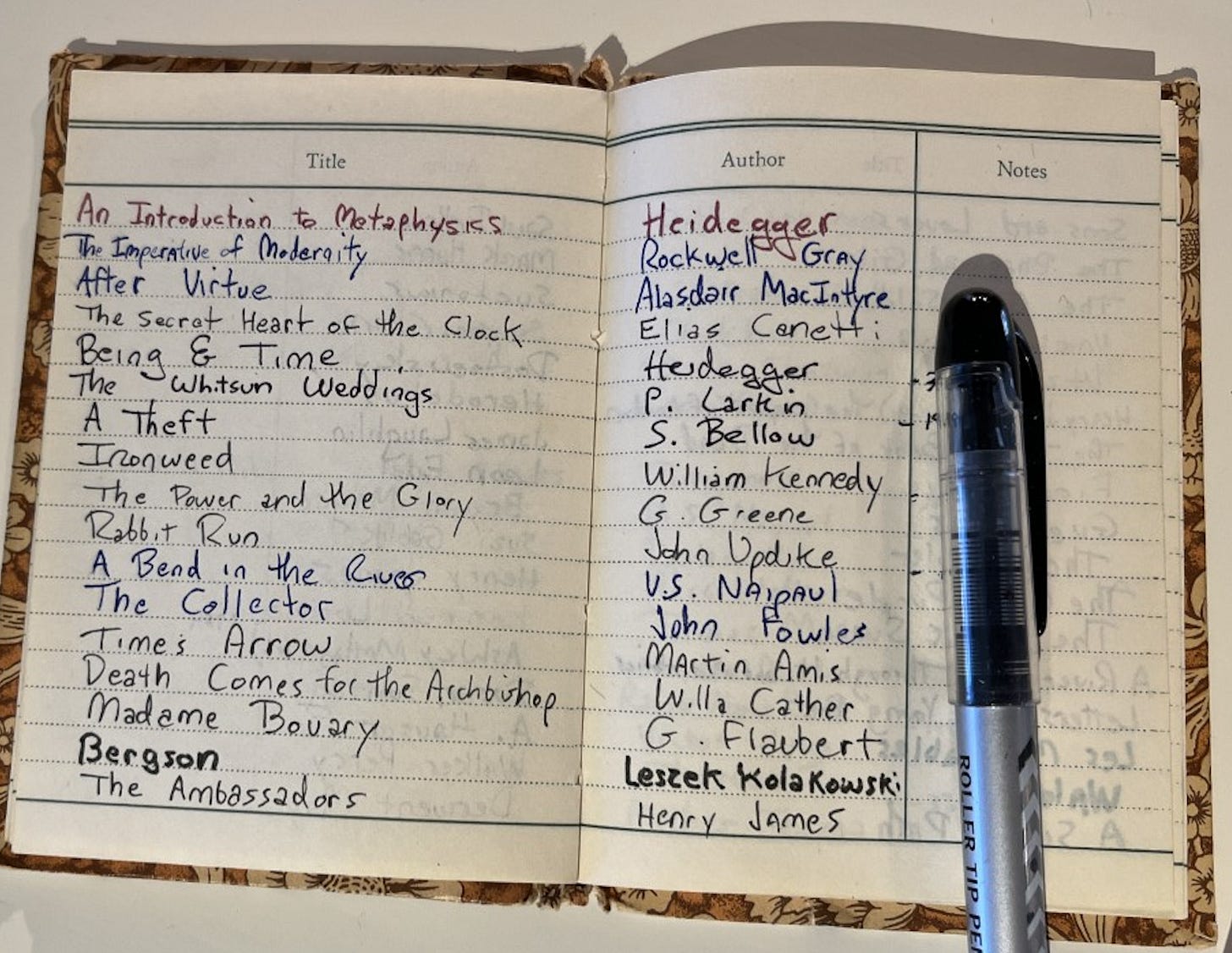

For example, below are some of the books I read around the time I turned 30. I note that I was working ridiculous hours at this point in my life, and NONE of these books had any relationship to my daily activities and responsibilities.

That’s the way I like it. My reading is holistic, not project-driven.

I have countless pages filled up with jottings of titles and authors. Here are some more books I read around that same time.

By the way, if I read a book for work or research, I didn’t even put it on the list. My lifetime reading plan has nothing to do with practical matters like getting a paycheck.

So you will note that there’s not a single book specifically about music here—and that’s by design. My reading plan is the fuel for my inner life, which I tried to keep separate from my career (another reason why I’ve never discussed this before). Eventually the two things—inner life and external vocation—got connected, as I describe below. But nobody was more surprised by this than me when it happened.

That’s so much the case that, even now, sharing this here seems risky to me.

But as I said above, people are curious about these things, and a few of you will benefit from this. I know that for a certainty. Not many, but a few. So I’m sharing my behind-the scenes methodology for these individuals.

I IDENTIFY GAPS IN MY READING EDUCATION, MAKE LISTS OF BOOKS I NEED TO READ TO FILL THE GAPS—THEN I READ EVERY BOOK ON THE LIST

The first time I did this was around the time I graduated from Stanford Business School. I had now completed my formal education, but there were still huge gaps in my learning—so many essential books that I still hadn’t read.

So one day, I sat down and made a list of the 50 most important books that I still hadn’t read. During the subsequent months, I read every book on that list.

When I finished all those titles, I decided that I now knew novels, poetry, social studies, and philosophy at a deep level, but I still lacked sufficient knowledge of history. So I made another list of history books, going back to Herodotus and the Egyptians and Sumerians, and continuing all the way to the modern times. Once again, I read every book on the list.

By the time I reached the age of forty, I was well read. I might even say I was wickedly well read. I could match up with professors at Harvard or Oxford. And here’s the oddest part of the story—I could even talk to them about their specialties, but for me this was all disinterested and outside the scope of my vocation.

They were often shocked. I had professors ask me with a strange, unsettled look in their eye: How does a jazz musician know so much about Aristotle? Or: How were you able to quote that passage from Ovid in the original Latin? Or: How in the world did you know about that book?

It was hard to explain that this was just my extravagant hobby.

But that’s not quite right either. A hobby doesn’t deliver the kind of results I got from my reading plan. Stamp collecting won’t do it. Video gaming won’t do it. Playing bridge won’t do it.

In fact, the benefits of this education were extraordinary. Off the charts. Boffo in every way. I can’t even begin to convey this in words—which is ironic because this whole plan was built on words. I didn’t even expect to get these benefits, but they happened anyway.

I will try to describe what happened, even if it isn’t easy. I should say upfront, that it happened almost without me noticing it. But I absolutely noticed the results.

Once I got into my forties, with all this deep learning behind me, it somehow gave me an aura of gravitas I’d never possessed before. People started treating me differently—and not because I made any demands. Not in the least. I’m not the kind of person to make demands.

And it wasn’t like I was quoting Shakespeare and Plato all the time. I tended to keep this literary education hidden from view, except when it was absolutely relevant to the situation at hand—at least hidden from direct view. But the nature of this kind of training is that it still shows up indirectly. And that’s what happened in my case.

In some ways, I was the last person to figure this out. But I saw the changes reflected in the other people I dealt with. It took me a long time to connect all this to the books I’d read.

But what else could explain it?

When I spoke before an audience, this behind-the-scenes project seemed to give my words an authority and resonance I hadn’t possessed in my youth. People were now trying to hire me for all sorts of crazy projects—giving sales presentations or negotiating million-dollar deals—because of this aura.

I couldn’t even begin to tell you all the wild and crazy ways this changed my life. People felt I had something that they could monetize. They wanted to enlist me in all kinds of schemes. They still do—although I turn them down. God knows what my life would be like now if I hadn’t learned how to say ‘no’ to these folks.

But empire-building of any sort had never been my goal. I had done all this for disinterested reasons.

And even if I walked away from the profit-making schemes, the intangible rewards were huge.

WHEN I WAS YOUNG, I READ OLD BOOKS. WHEN I GOT OLD, I READ YOUNG BOOKS

I took this approach for both books and music. And it might be the most unconventional part of the whole project.

Most young people listen to new music and only become less interested in the current hits when they get older. The same thing tends to be true of books too—the younger generation wants to read stuff that’s current and hip and up-to-date.

I did the exact opposite. I learned the tradition and heritage first, and only then felt I had the proper perspective for the current day.

When I was twenty, I almost never read a book by a living writer. Nowadays, most of the books I read are by living writers. I wasn’t quite as extreme in my music listening habits, but I still focused primarily on the tradition when I was learning how to be a pianist and critic. Today I’m much more focused on new music.

This makes perfect sense to me. But others are often puzzled by it.

Some people wonder why I didn’t start writing about literary subjects until I was middle-aged. The brutal truth is that I wasn’t ready to do it until around age 40. I needed to assimilate the tradition and take some measure of the greatest works of the past before I really had any sense of what a novel or epic poem or some other masterwork was really all about.

But I also enjoyed the old books when I was a young man. I found it liberating to master the tradition. That was far more exciting to me than reading a stack of bestsellers of the current moment.

I realize how strange this aspect of my plan has been. I know people who love old books, and continue to read them all their lives. I also know people who love new books and never change. And there are those folks who become more traditional as they get older. But my calculated plan to shift to the new as I get old is an outlier.

But this whole reading plan was designed just to please myself.

In that regard, I succeeded marvelously. My daily reading is my proven path to Nirvana, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

Okay, that’s my testimony on my lifetime reading plan, and how it worked for me—even without me trying to make it work. At a later date, I’ll tell you about the mistakes I made along the way. Even if I ended up in a good place, I could have done all this reading and learning in a better way. But that’s a story for a different day.

"I needed to assimilate the tradition and take some measure of the greatest works of the past before I really had any sense of what a novel or epic poem or some other masterwork was really all about."

Call me crazy (or homeschooled) but isn’t that how humanities classes are supposed to or used to work?

My older sister and I took a humanities class together in high school (again, homeschooled). We discovered that we absorbed the material much better if we read it aloud, so we read it ALL aloud together. The Iliad, Odyssey, Aeneid. Gilgamesh. Shakespeare. Dante. Milton. It was an amazing experience, and it actually took less time than reading it silently alone, because we never found ourselves glazing over and reading the same sentence again and again or any of the other things that happen when you try to read something too difficult. I recommend it to everyone.

Ted, you may be unique in the thoroughgoing organization of your reading time throughout decades, but in terms of yearning for genuine wisdom from a young age, you were never alone.