Let's Give Duke Ellington the Pulitzer Prize He Was Denied in 1965

Last week, the IOC reinstated Jim Thorpe's 1912 Olympic gold medals—it's time to do the same with Duke Ellington's Pulitzer

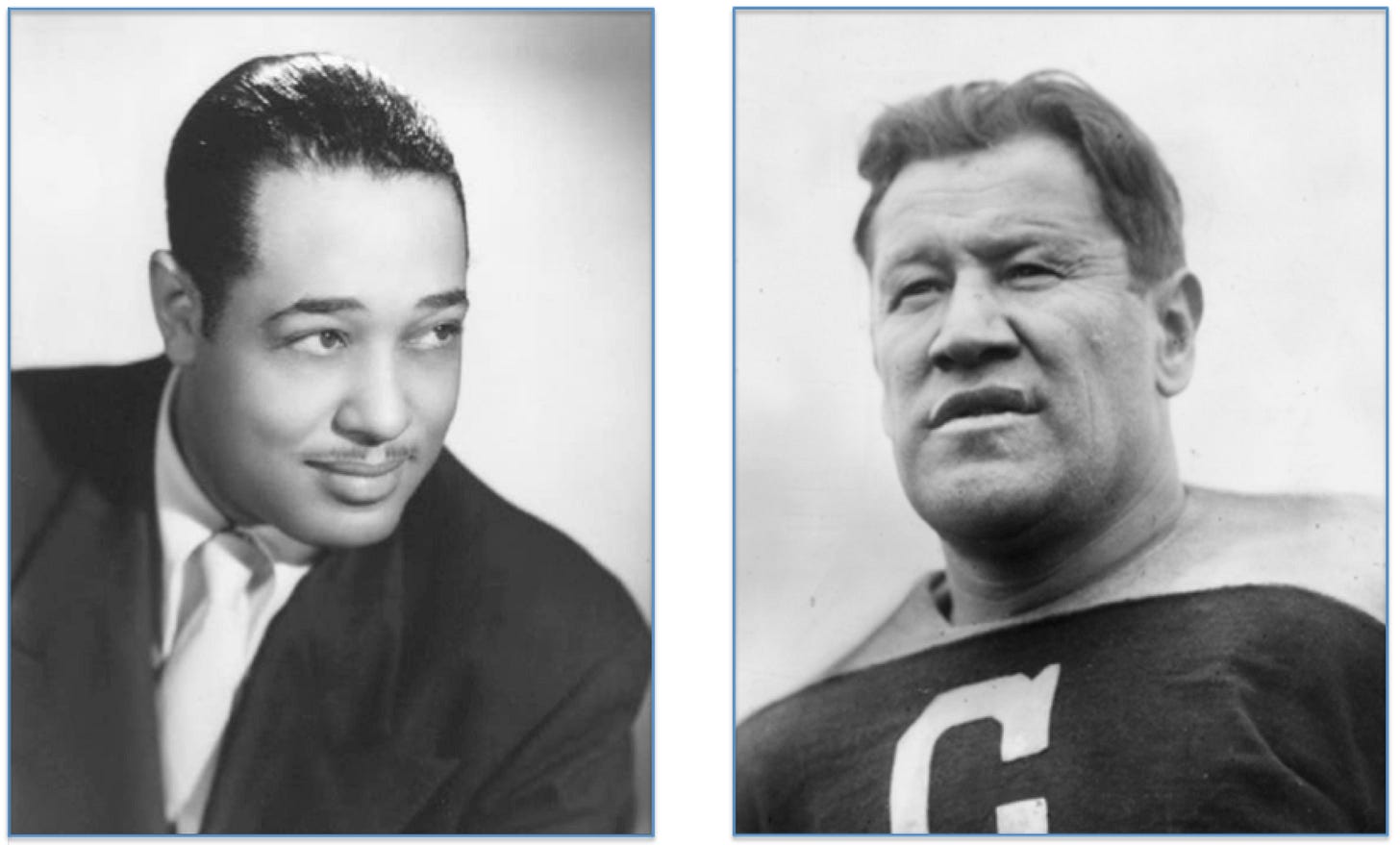

Last week the International Olympic Committee reinstated Jim Thorpe’s gold medals, taken from him in 1912. Emboldened by this rectification of a longstanding wrong after more than a century, I am launching an online petition for Duke Ellington to be granted the Pulitzer Prize he was denied in 1965—despite the recommendation of the music jury.

Here’s the link to the petition. The back story is below.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Let's Give Duke Ellington the Pulitzer Prize He Was Denied in 1965

by Ted Gioia

Something amazing happened in sports last week. And it didn’t take place in a competition or on an athletic field.

Jim Thorpe, a legendary athlete in almost every sport he played, was retroactively awarded sole possession of the Olympic gold medals for the 1912 pentathlon and decathlon.

It had taken 110 years to redress a wrong.

Thorpe destroyed the competition at the 1912 Olympics and set records that lasted for decades. At the medal ceremony King Gustav V of Sweden declared that he was “the greatest athlete in the world”—and nobody disagreed. But a few months later, Jim Thorpe was stripped of the awards because he had played a few games of semi-pro baseball, and thus violated the Olympic rule that only amateurs could compete in events.

In my childhood, my parents and others of their generation still complained bitterly of this. Thorpe had lived for a time in my home town of Hawthorne, California, and though he died four years before I was born, many still remembered him, and his name was always spoken with awe and reverence.

But the lost medals were especially lamented by the Native American community—Thorpe was a member of the Sac and Fox nation, and he was not only a great athlete, but at the very highest rung. When the Associated Press conducted a survey in 1950 to pick the best athlete of the first half of the 20th century, Thorpe took the top spot. When they did another vote decades later to cover the entire century, Thorpe placed third, behind only Babe Ruth and Michael Jordan—an extraordinary achievement, especially given the fact that Thorpe’s glory days were only a dim memory by that time.

I never expected Thorpe to regain sole possession of those 1912 gold medals. But it happened. And it was the right thing.

And that leads me to the subject of Duke Ellington and the Pulitzer Prize he never got in 1965.

If you look at the list of winners of the Pulitzer Prize in Music from the 1960s, you see a strange gap. Here’s what it looks like on Wikipedia.

That missing award from 1965 has long been a source of disappointment and frustration to jazz fans, and a genuine disgrace in the history of the Pulitzer. The jury that judged the entrants that year decided to do something different—they recommended giving the honor to Duke Ellington for the “vitality and originality of his total productivity” over the course of more than forty years.

This was an unusual move in many ways. First, the Pulitzer usually honors a single work, much like the Oscar for Best Picture or other prizes of this sort. In this instance, the jury recommended that Ellington get the honor for his entire career. But even more significant, it would be the first time a jazz musician or an African-American received this prestigious award.

But it never happened.

The Pulitzer Board refused to accept the decision of the jury, and decided it would be better to give out no award, rather than honor Duke Ellington. Two members of the three-person judging panel, Winthrop Sargeant and Robert Eyer, resigned in the aftermath.

As it turned out, no jazz work would receive this honor until Wynton Marsalis took home the Pulitzer in 1997 for his Blood on the Fields. Since that time, jazz has been occasionally recognized, and even Ellington got a special citation in 1999—one of a number of posthumous awards that the Pulitzer started giving out, largely as a rearguard action to deflect criticism of past omissions.

But the recent action of the International Olympic Committee sets an admirable precedent. Let’s give Duke Ellington the 1965 award. If the IOC can set matters straight after 110 years, the Pulitzer Prize Board can certainly revisit a decision only half as old.

And in this instance, nobody gets their prize taken away. In that regard, it’s more straightforward than even the Olympic case. The slot is open, and Duke deserves it. That’s why I’ve launched a petition asking the Pulitzer Board to take this honorable step.

“Fate is being kind to me,” Ellington told the press. “Fate doesn’t want me to be famous too young.”

The story behind the denied prize is worth revisiting—especially for the insights it gives us into Ellington and how he viewed his artistry and legacy.

He was on the road with his band when the Pulitzer news story broke, and journalists sought him out for a comment. What was Duke’s reaction to coming so close to winning the biggest award in American music, only to have it snatched away at the last minute?

Ellington always had something eloquent and decorous to say, no matter how awkward the situation, but in this instance he was sorely tested. This would have been an extraordinary moment for his career, his race, his genre, and his artistry. But his response was every bit as dignified as one expects from a Duke:

“Fate is being kind to me,” he told the press. “Fate doesn’t want me to be famous too young.”

I note that he was 66 years old at the time, and in the final decade of his life.

“What else could I have said?” Ellington later elaborated. “In the first place, I never do give any thoughts to prizes. I work and I write. And that’s it. My reward is hearing what I’ve done.”

A few hours later, he was back on the road, driving alongside his longtime traveling companion, baritone saxophonist Harry Carney. He was already worrying about the next gig, the next composition, the next recording session.

Ellington wasn’t lying about his priorities. One of my favorite anecdotes about the bandleader tells of his friends trying to come up with a special gift for Duke’s 60th birthday. They decided to track down the scores of his illustrious compositions, make clean copies of each and have them published in a one-of-a-kind set of bound leather volumes. Much of the music had been lost, but a copyist was hired to work in secret on transcribing parts from records.

All in all, it was a huge amount of work. And finally the birthday arrived, and Ellington was given these extraordinary books that contained his life’s work. And how did Duke react? Once again with charm and dignity. “He made polite noises and kissed us all,” recalled Arthur Logan, who had initiated the plan behind the gift volumes. “But, you know, the son of a bitch didn’t even bother to take it home.”

True to his word, Ellington was far too preoccupied with what he would do tomorrow—and that gave him no time to think about what he had done yesterday, or last year, or back in the 1930s and 1940s.

So I don’t think we need to give the 1965 Pulitzer Prize to Duke Ellington to placate his ghost, or even ensure his legacy. That’s already rock solid.

We do it because it’s the right thing. It enhances the prestige and legitimacy of the Pulitzer—and every award needs that nowadays, when many have grown skeptical about our leading prizes. And it’s the proper thing for the music—because every time genuine artistry is recognized it sets an example for the present generation, and lays a foundation for the future.

And it’s so easy to do. That 1965 slot for the Pulitzer Prize in Music is empty. Giving Ellington his belated award fills that gap. And nobody—absolutely nobody—fills it better than him.

Fate may not have been kind, denying him the award back then. But at least let’s give fate a chance to be fair over the long haul.

You can sign the petition here.

Great article, Mr Gioia …. totally agree with both the sentiment and morality of your case …. more than happy to sign your petition.

Though I was born in England in the 50’s and a ‘Child of the 60’s’ my parents were avid fans of American swing bands and the jazz of the 30’s and 40s. … they had many of the records of their era and played them endlessly. I of course, being a teenage fan of Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin (and the other Rock bands of the 60’s) thought my parent’s music was old fashioned and boring. It only took me about twenty years to learn the error of my ways and to develop an appreciation of the immense talent and artistry of musicians like Duke Ellington and Ella. Who was it that said ‘youth is wasted on the young’? I sincerely hope you succeed in your petition and that America does right for one it’s greatest national treasures.

Cheers,

Neil

P.S. only recently found your channel and am totally enjoying the quality of your writing and the energy of your insights - keep up the good work - thanks.

How fortunate we are that there are musical artists that walk among us, that when asked why they create, reply, "My reward is hearing what I've done."