I Ask Seven Heretical Questions About Progress

And I offer seven radical hypotheses. But can you handle the truth?

An editor recently asked me to write an article about progress for a journal specializing in that subject.

I had to decline—for a variety of reasons. But mostly because I knew that advocates for progress would HATE what I have to say.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

I felt a little bit like Jack Nicholson as the movie general who exclaims: “You can’t handle the truth.”

That pretty much sums up how I feel about the current debate over progress.

Yet here’s the strange thing: I absolutely believe in progress.

I fervently desire progress. I work to create progress in the world. I do it everyday—both in my personal sphere and in the world at large.

But there’s a tiny problem here—or, actually, a huge problem: I don’t measure progress the same way other people do.

In many ways, my standards for progress are the exact opposite of the prevailing metrics.

Talking about this will just get some people riled up. But I put “Honest Broker” on my business card—so you deserve to know all the dirty details.

Hence I squelch my inner Jack Nicholson. And instead I offer below: Seven Heretical Questions (and Seven Radical Hypotheses) About Progress.

RELATED ARTICLES

This article on progress is part of an ongoing series. In the articles linked below, I interpret troubling signs of cultural stagnation or dysfunction, and identify rising counter movements—or what I call an alt culture. These alternatives to the status quo are gaining great momentum, but are still poorly understood by prevailing narratives, probably they defy so many entrenched interests.

15 Observations on the Emerging Vertical Dimension of Culture Conflict

How Corporate America Killed a Lifestyle That Threatened Its Dominance

In 2024, the Tension Between Macroculture and Microculture Will Turn Into War

Seven Heretical Questions About Progress

(and Seven Radical Hypotheses)

By Ted Gioia

Let’s start with the heretical questions.

And if you can handle the truth, keep reading until you get to the hypotheses at the bottom of this article—because that’s where I get really outrageous.

1.

Late in her life, my mother worked at organic farming—and sometimes sold fruits and vegetables at a roadside stand. It was hard work and her produce was expensive, but she could vouch that it was healthy and free of chemicals.

She was farming and selling the same way they did back in the medieval era. That actually was her goal.

Here’s a brief story that will tell you a lot about my mother:

One day, I asked: “What do you want for your birthday?”

MOM: “A load of manure.”

TED: “Say what?”

MOM: “You heard me. I want a load of manure.”

TED: “I can’t do that—what son gives their mother a cart of poop for her birthday?”

I got her some other gift. But I still feel bad about it. I let her down—I should have given her the manure. She really cared about those crops.

But this marked a big change from my childhood. In the early days of her marriage, Mom wanted to embrace progress and the newest technologies in all matters related to food.

For her generation, these huge leaps forward were frozen foods and canned goods.

What amazing progress! Those frozen meals were

cheaper than the alternatives

lasted longer (almost forever, really)

easier to prepare

And even offered a balanced, healthy diet—you can tell just by looking at the picture on the box.

Anyone who doubted that this represented progress, just had to look at the name on the carton: TV Dinner. They actually named the meal after the most high tech gadget in our home.

You can’t get more futuristic than that. (By the way, why don’t we have TikTok Dinners and iPhone Meals nowadays?)

So here’s my first heretical question: Why did my mother abandon the most innovative food technologies of her generation and return to laborious and expensive organic foods—raised according to the farming standards of the Middle Ages? How could this possibly be a step forward in the modern world? Or was she just a fool?

2.

Nobody invests more in progress than Mark Zuckerberg. He is everywhere—building the future of virtual reality, the metaverse, social media, and (now) AI.

And when Zuckerberg invests in the future, it impacts billions of people. They spend countless hours on his platforms—Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Threads, and others.

If anybody knows (and controls) progress it’s Mark Zuckerberg.

So why is he building a personal bunker designed to survive the Apocalypse?

Other tech titans have similar plans.

Peter Thiel’s post-Armageddon bunker was so extreme, the New Zealand government shut it down.

Before his collapse from billionaire status, Sam Bankman-Fried planned to “purchase the sovereign nation of Nauru in order to construct a 'bunker/shelter' that would be used for 'some event where 50%-99.99% of people die.”

Elon Musk may actually be considering a move to Mars.

Here’s my second heretical question: How much is progress really worth if the people at the forefront of it anticipate global collapse in their private lives?

3.

I love genuine progress where I see it—and I’ve often seen it during my lifetime. For example, Jonas Salk announced the development of the polio vaccine two years before I was born, and it was commercialized around the time of my 4th birthday.

I benefited from that. And the same is true of the other medical breakthroughs of the middle decades of the 20th century. I might not be alive today without the invention of penicillin and other antibiotics, or various vaccines and treatments of recent decades.

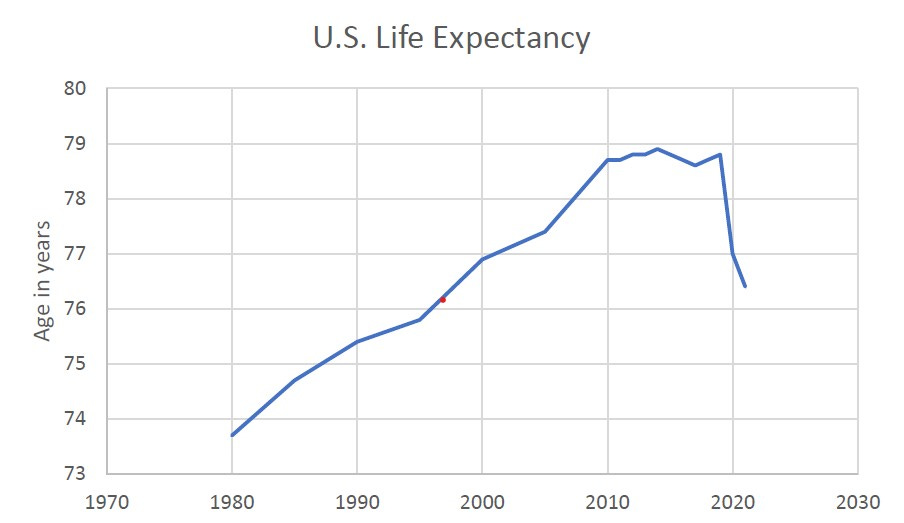

The bottom line: When I was born, the average lifespan of an American was 69 years—but recently it reached 79. Of course, this is more than just medicine—cars are safer, air travel is safer, etc.. But this all falls under the rubric of progress. In total, it’s added a decade to expected lifespans since I was born.

But how crazy is this next fact. Lifespans are now shrinking in the US—and this started even before COVID. US life expectancies reached their peak a half-decade before the pandemic.

This defies all the rules.

All those cures and medical breakthroughs from my childhood happened when the US only allocated 5% of GDP to healthcare—nowadays it’s closer to 20%. You could hardly spend more on health than we’re doing right now.

And every other aspect of technology related to lifespans (auto safety, etc.) receives enormous investment and administrative support.

This leads to my third heretical question: How can huge investment in advancing medical and safety technology result in shorter lifespans? This is the single biggest area of private investment in the entire US, and things are getting worse. If this is what progress looks like, why should I want more of it?

4.

A few months after I graduated from high school, my parents moved from Los Angeles to the middle of nowhere.

Maybe that’s not fair. They actually moved to a poorly-built home on a dirt road in Sebastopol, California—completely off the grid except for an electricity connection to the power lines.

Nowadays, I realize that this was a very cool move on their part. But that’s not how I saw it at age 18.

I was horrified back then.

I’d spent my high school years cruising around LA, going to Hollywood movie premieres, and hanging out at the beach. Now when I came home from college, I was stuck at the intersection of Dullsville and Green Acres.

My parents were rejecting progress—they didn’t even have garbage collection (just an outdoor sump). Or city plumbing—they got their water from a well. And soon they would start organic farming (see item #1 above).

It gets worse: Sebastopol had passed laws against chainstores in the downtown area. So there was no Walmart, no Target, no Best Buy, not even a sucky Olive Garden. Instead there were a bunch of mom-and-pop stores owned and operated by people who also lived in the community.

The city’s biggest source of employment was growing apples—I kid you not—almost as if the economy hadn’t advanced since the days of Rip Van Winkle.

But here’s the sequel—and it makes no sense: Everybody today wants to move to this same city, and property values in Sebastopol have skyrocketed. That off-the-grid home was the smartest financial investment my parents ever made. And the downtown is now praised as quaint and picturesque—so much cooler than nearby cities with their Walmarts and Olive Gardens.

People actually move from Silicon Valley, the global epicenter of innovation, to lowly Sebastopol and its apple (not Apple) economy. Who could have ever anticipated that?

So here’s my fourth heretical question: Why did property values go up so much in a city that rejected progress and efficiency in almost every possible way? Why do so many people want to live and work there today? Why would they move from Silicon Valley to a boring farming community?

5.

The most popular technological innovation of the 21st century is the smartphone. By any economic measure, this represents a huge leap forward.

This tiny gadget replaces dozens of other devices—putting everything into the palm of my hand. My smartphone gives me immediate access to information, entertainment, and photos of the wardrobe and culinary choices of millions of strangers.

What’s not to like?

But the rise of the smartphone has been accompanied by a frightening increase in psychological illness and toxic social behaviors of all sorts. People are literally addicted to their phones.

Just consider these statistics, repeated verbatim from Exploding Topics:

“47% of Americans admit they’re addicted to their phones.”

“The average American checks their smartphone 352 times per day.”

“71% of people spend more time on their phone than with their romantic partner.”

“Almost two-thirds of children spend four hours or more per day on their smartphones.”

“44% of American adults admit that not having their phones gives them anxiety.”

“Cell phones cause over 20% of car accidents.”

This is ominous. But the story gets worse—because screen time is now linked to:

depression

anxiety

obesity

physical illness (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular problems, etc.)

self-harm

learning disorders

divorce

suicide

violent crime

So here’s my next heretical question: What does it tell us about progress if the most influential technological innovation of the century is clearly destroying lives on a massive scale?

6.

I now can ask AI chatbots to write articles for me. It’s unbelievably cheap and fast. I can save hours every day—giving me so much more time to doomscroll on my smartphone.

It’s a bloody shame that those AI bots get so many facts twisted or plain wrong. And they keep on plagiarizing. At best, they’re just regurgitating text from human writers—because that’s how they learn in the first place.

But the biggest problem is that readers hate this AI stuff. That’s why Sports Illustrated stirred up so much outrage when it created fake bios of non-existent journalists—and pretended that these folks had written the AI articles.

After this was discovered, Sports Illustrated was publicly shamed. And (a few weeks later) went totally out of business.

I’m in the same bind. If I switch to AI, and readers find out, I’ll lose most of my subscribers almost instantly.

That doesn’t seem fair.

Here’s my next heretical question: All the experts tell me that AI is the biggest leap of progress of our time, and nothing else is even close—so why do companies that use AI hide it? Why do consumers hate it? Don’t people want progress?

7.

I got my first audio system when I was in ninth grade (a reward from my parents for winning a local speech contest). It included a turntable, radio, and surprisingly good speakers—with much better sound quality than any of my current digital devices.

This changed my life.

But it was like giving a needle to a junkie—I now had to support my habit. And owning a record player can be even more costly than drugs. At least for me—I spent way too much money on jazz records. During my grad school days, I even cut back on food so that I could afford more of those bad boys.

I took these records more seriously because I had paid so much for them. Even an album I didn’t like got repeated hearings at the turntable—otherwise how could I justify the expense?

This entire process was inefficient and outmoded. Today I have access to millions of albums (without paying for any of them)—all because of technological innovations. I hardly spend anything on music, just a tiny monthly subscription fee. And I can play music almost anywhere and everywhere.

This must be progress, no?

But that old antiquated audio system gave me a deep and intense relationship with music—with benefits impossible to replicate today. Just having access to the liner notes on the back of the albums had an amazing impact—educational, and aesthetically mind-expanding.

Those vinyl albums came with much more information than the streaming platforms can match. The audio quality was superior. And the simple fact of ownership made me treat the entire experience more seriously.

I should add one final fact: the vinyl album economy allowed musicians to earn a decent living from their art.

So here’s my final heretical question: Is it really progress if technological innovation degrades the listening experience, erases all the supporting information about the music, and impoverishes the artists who create the songs in the first place?

So much for heretical questions.

But let me move on to my radical hypotheses. (I’m running out of space, so these are much shorter.)

But each of these is a huge issue—and my views get more heterodox as you work your way down the list.

So I will need to write about this more in the future.

Progress should be about improving the quality of life and human flourishing. We make a grave error when we assume this is the same as new tech and economic cost-squeezing.

There was a period when new tech improved the quality of life, but that time has now ended. In the last decade, we’ve seen new tech harming the people who use it the most—hence most so-called innovations are now anti-progress by any honest definition.

There was a time when lowering costs improved quality of life—raising millions of people out of poverty all over the world. But in the last decade, cost-squeezing has led to very different results, and is increasingly linked to a collapse in the quality of products and services. Some people get richer from these cost efficiencies, and a larger group move into more intensely consumerist lifestyles—but none of these results (crappy products, super-rich elites, mass consumerist lifestyles, etc.) deserve to be called progress.

The discourse on progress is controlled by technocrats, politicians and economists. But in the current moment, they are the wrong people to decide which metrics drive quality of life and human flourishing.

Real wisdom on human flourishing is now more likely to come from the humanities, philosophy, creative and artistic spheres, and the spiritual realm, rather than technocrats and politicians. By destroying these disciplines, we actually reduce our chances at genuine advancement.

Things like music, books, art, family, friends, the inner life, etc. will increasingly play a larger role in quality of life (and hence progress) than gadgets and devices.

Over the next decade, the epicenter for meaningful progress will be the private lives of individuals and small communities. It will be driven by their wisdom, their core values, and the courage of their convictions—none of which will be supplied via virtual reality headsets or apps on their smartphones.

I still have more to say on this. But that’s plenty to chew on for the time being.

What a thoughtful post! I'm not sure whether some or all of the questions are rhetorical, but I'll give answers, nonetheless.

1. Your mother rationally prioritized healthy eating. That's unfortunately a luxury for most.

2. Zillionaires spending money they don't need as an insurance policy against an apocalyptic event, however unlikely, is rational.

3. Health is better than ever for those who can afford it. There's a shameful ten year gap in life expectancy between the riches and poorest male 1%. That's an awful choice we as a country are making.

4. I suspect the move inland is relative value, i.e., still more house and space for your money inland than on the coast.

5. I think the evils of the smartphone were an unintended consequence. There are benefits as well to those who resist obsession.

6. We all want authenticity. To the extent AI interferes with authenticity, it will and should be shunned.

7. I'm 100% with you here. First album at the age of ten was Elton John "Don't Shoot Me, I'm Only the Piano Player." I played it over and over and communed with those songs.

I'm also 100% with you on your last three conclusions about values and wisdom of the humanities and personal and intimate interactions in real life in small groups. Nothing more precious or important to human flourishing.

We don't have an authentic culture anymore.

From the day we're born we're inundated with commercials from bigger and bigger corporations telling us what we need to be happy

And these recommendations are always what will make them richer, not make society richer.

The only reason the USA spends so much on health care is it benefits large corporate entities

And that is the only goal, not to extend lives, but to make money for people who already have too much of it.

Studies have shown a single payer Healthcare system would save 10s of thousands of lives a year and reduce bankruptcy by a huge amount.

But the rich might have to pay more taxes so it will never happen.

You can't have an entire society based on greed and rent seeking and expect it to be Shangri la.