I Answer 18 Questions

I tell tales, give advice, and make wagers on the future

I recently answered some questions from Sam Kahn for The Republic of Letters, a very smart Substack hub for culture writing.

I’m sharing my responses below, for your possible diversion—or maybe even entertainment.

Please support my work by taking out a premium subscription—just $6 per month (even less if you sign up for a year).

When you meet somebody at a party, how do you describe what you do?

I avoid talking about myself in those settings. We invited our neighbor over for dinner last week, and I was able to spend two hours in conversation and never mention my vocation, not even once—he has no idea what I do for a living.

He owns a ranch about 100 miles from here. I enjoyed talking to him about that. We had a lovely evening.

You really do learn more listening, not talking. I’ve watched smart people achieve amazing things just by keeping their mouths shut. Isn’t that how Claudius became Roman emperor?

But if I’m in a situation where someone absolutely insists on knowing what I do, I just admit that my life story makes no sense whatsoever. I’ve done lots of things and the connections between them are hard to discern.

They probably don’t even exist.

Really?

Okay, maybe that’s not entirely true.

A few years ago, the different threads of my life started to come together. Maybe that’s just coincidence, but maybe it’s also my destiny.

For example, I might write an article about music or movies or books, but I’ll find myself drawing on analytic tools I learned at the Boston Consulting Group or McKinsey. I now do that without even thinking about it—although for many years I kept those two parts of my brain locked in separate rooms.

Or I might dig into my early training in philosophy while evaluating digital tech platforms. Or I might draw on stories from my various alternative careers—those crazy day gigs I did for too many years—to illuminate something happening in the culture right now.

So maybe it does all fit together on some level. But at heart I’m just like a jazz musician who makes it up as it goes along. I only see the pattern after the song is over.

Didn’t Kierkegaard say something like that? Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.

How much does your jazz background shape your work today?

Jazz isn’t just a music genre. It’s also a way of life. If you embrace it, you learn how to go with the flow—or, even better, change the flow.

Your life becomes bolder—less predictable and more interesting.

That reminds me of an explanation I heard from Stan Getz, who used it to justify all sorts of antics. When asked why he did something that others wouldn’t do, he replied: “I’m just an old jazz musician.”

So that’s how I’ll answer your original question—I’m just an old jazz guy. Everything else in my life builds on that.

It would be hard to call somebody with degrees from Stanford and Oxford an autodidact, but that's kind of how I perceive you— or maybe something like a 'life-long learner' is better?

I do focus on constant learning and mind expansion. I start every day by reading books for two hours—and then I do more reading at night, after everyone else has gone to bed.

So I am an autodidact, although I benefited from the best education that money could buy—or, to be more accurate, the best education student loans could buy. But in most situations, I taught myself.

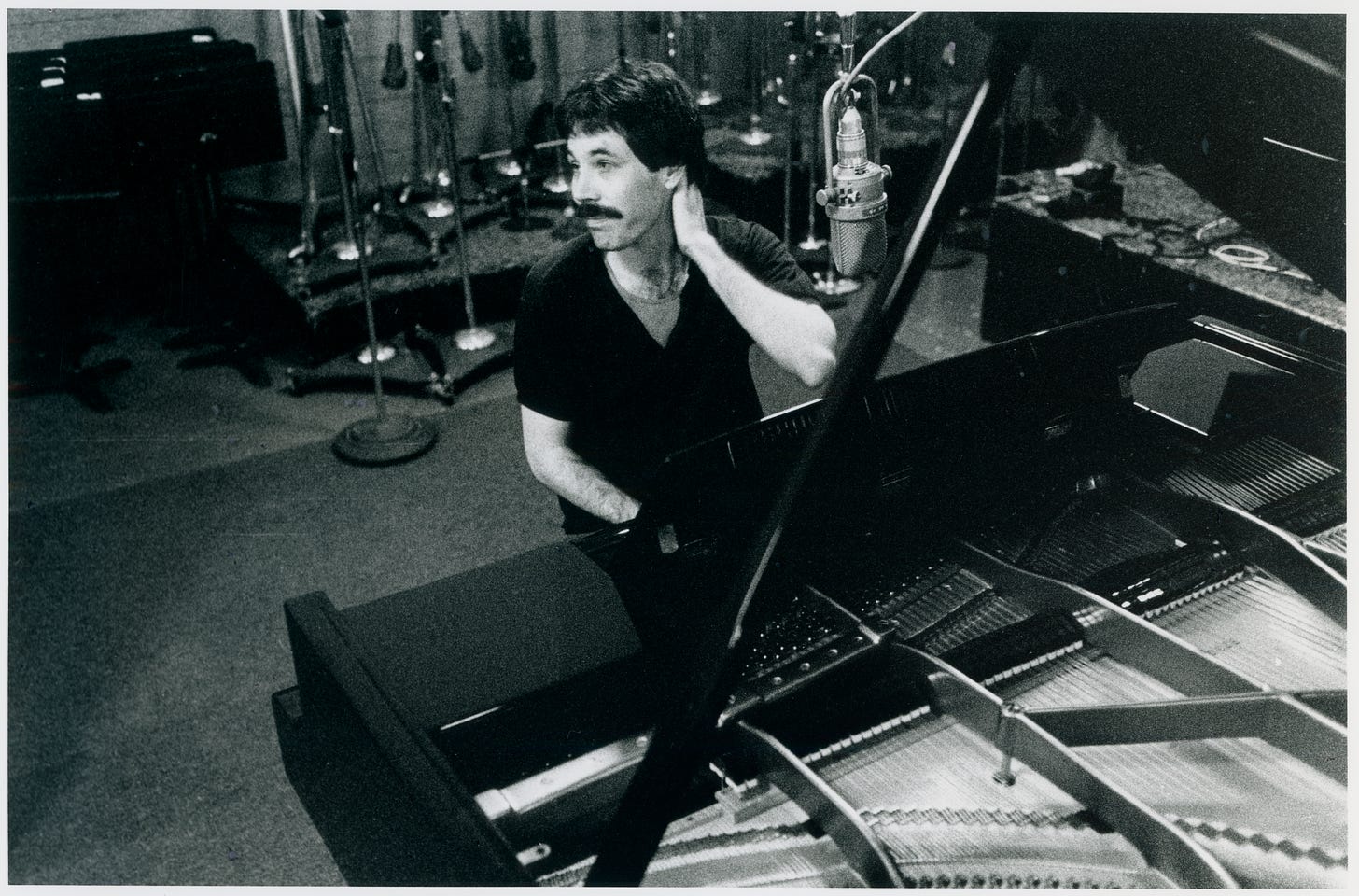

Consider my involvement in jazz. I learned it on my own, without any teachers. But that never held me back. I performed and composed, recorded and produced, taught and mentored students, even got hired by the Department of Music at Stanford—without ever getting a music degree.

I’ve done that in other situations. The key is to operate without fear—there’s no limit to what you can you achieve if you embrace experiences, and ignore gatekeepers.

You seem to have a catholicity of what you're interested in, to steer clear of compartmentalization, to have an idea that wisdom comes from broadly taking in life as opposed to just moving forward on a vertical career trajectory, and to be engaged in a project of continuous self-growth.

Is that a fair assessment of your outlook? If I'm describing that broadly right, is that outlook something you consciously settled on or is that just kind of how you are?

It’s great to learn the rules. But it’s even better to invent your own rules.

That gets some people upset. If you bypass the formal credentialing process, the gatekeepers might never forgive you.

But even my approach isn’t always right. In my youth, I would have studied with a jazz teacher if I could have found one—but they didn’t exist in my neighborhood. So I taught myself by sheer necessity.

That’s the best skill you can learn—how to teach yourself. Over the long run, that’s worth more than an Ivy League degree.

Can you share with Republic of Letters readers a bit about your reading habit—you seem to be kind of the Wim Hof of reading. To what extent are you molded by that scale/volume of reading?

I don’t read for career advancement. I don’t read for skill building. I don’t even read for fun—at least that’s not my main priority.

Of course, I do get all of those things from my reading. I get enjoyment from it—and expand my skill base and even earn money. But those are indirect benefits, not the actual purpose or motivation.

I read in search of wisdom. I’m sure that sounds goofy to some people. Or naive or old-fashioned. But you don’t pursue these lifelong goals without sufficient motivation—and the pursuit of wisdom is that for me.

So I always seek out books by the wisest people—most of them are dead. (By the way, that’s not a requirement.)

I’ve been doing this for fifty years, more or less. The cumulative impact of this is incalculable. You can’t measure it in dollars—but people do try to hire me because of the intangibles gained from this lifelong reading.

If you immerse yourself in the great wisdom traditions and creative masterpieces, and do it consistently over the course of decades, you will achieve a gravitas, poise and confidence that others will want to monetize.

But even at that point—or especially at that point—you need to be judicious. You can destroy your gift by treating it as a tool of commerce.

You should never, ever sell yourself off to the highest bidder.

Your goals must be in alignment with your values, or the game isn’t even worth playing—no matter how much money they dangle in front of you.

What can you share about this mysterious, well-traveled, and well-remunerated work you were doing in your 20s and that you only ever obliquely refer to? What are some of the life lessons that you have from that period of time?

I did a lot of day gigs. That’s typical for people in creative fields. But instead of bartending or flipping burgers, I used my analytical skills. At a young age, I demonstrated an ability to navigate through complex situations, and find solutions others might have missed.

People hired me to do this, and I got better at it over time. I eventually developed a reputation as a futurist—somebody who could anticipate what might happen before it actually takes place.

My work often involved overseas travel. I made hundreds of trips outside of the US. At one point, I had to send my passport back to the State Department, and get more pages added to it—I had filled up the existing book with visas and immigration stamps and there was no more empty space in it.

These projects dealt with all sorts of situations. But they usually started because somebody had a problem, and needed a solution. It rarely was a simple matter—I typically operated in uncertain conditions where (as they say during war) the situation is fluid.

But, hey, that’s why they hired me. If it were simple, they wouldn’t need my help.

I mentioned this earlier, but it’s worth repeating: For a long time I saw this work as totally unconnected to my creative pursuits. But I don’t feel that way anymore. These experiences make me more effective in every sphere—for example, on Substack. Readers can sniff out frauds and posers, and I’d like to think that they come to me because I’m battle tested and real, not some hipster or phony.

Can you talk about how writing came into your life? How does writing balance itself out with some of your other endeavors—music, for instance? Do these conflict? Are they complementary? I would sort of suspect that there's a lifelong dialogue between them.

I loved stories as a child. I have fond memories of adults reading to me, and when I got old enough I started reading books on my own.

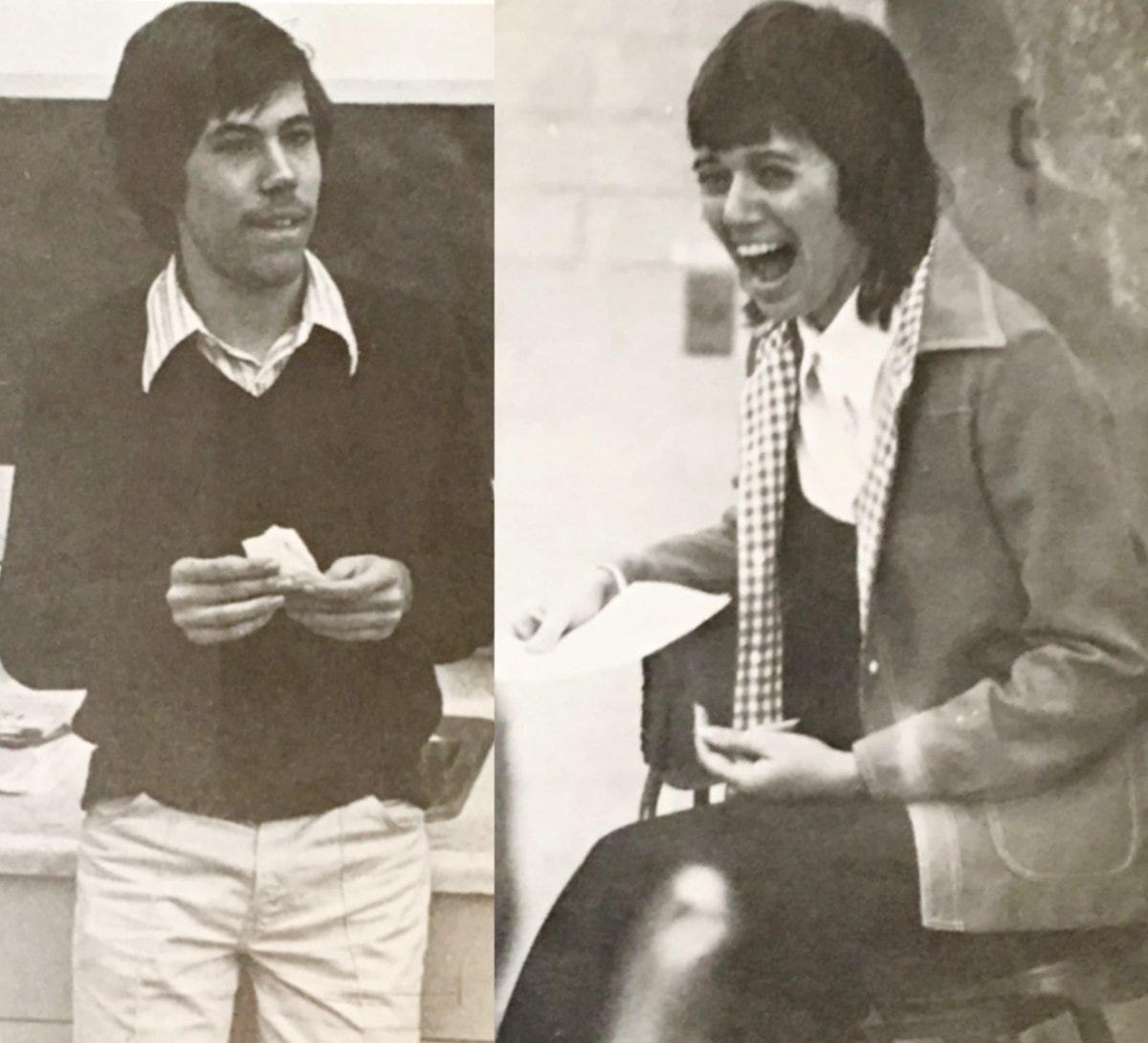

This quickly evolved to writing. I started writing my own stories around age nine or ten. In high school, I studied journalism and was editor of the school newspaper. I’m still in close contact with my journalism teacher Konnie Krislock, who played a key role in my development as a writer—starting when I was just 13 years old.

As you have noticed, I’ve done many things to earn a living over the decades—from playing the piano to problem-solving in foreign climes—but writing is now my main focus. And the writing draws on all these earlier experiences.

This is the challenge many young writers face. They need to experience life in order to write about it. But that takes time.

You can’t rush it. You can’t fake it. You need to live it.

Can you talk about how you found your way to Substack and about the way you built your audience?

I know that you had a reputation as a jazz critic, and a large following that way, but something unique seems to have happened with your Substack. There seems to be a more dedicated following for your work than I've seen for anyone on the platform. What are some of the factors that account for that?

I’ve often battled with editors. After I had some success as a writer, I thought they would give me more freedom. But the exact opposite happened.

Because my books on jazz sold well, they didn’t want me to write about any other subject. I actually enjoyed more freedom as a writer when I was starting out and relatively unknown. The system punishes you for success—because after that they want to reduce you to a formula.

For example, I was hired as a columnist for a major periodical. I won’t mention the name. But when I wrote a story that touched on financial matters, they got angry at me. They told me that this was outside my field of expertise.

You’re a jazz writer, buddy. Stick to your knitting.

I pointed out that I knew more about business than their business writers—and it wasn’t even close. It wasn’t just my Stanford MBA or econ degree from Oxford, or doing an IPO on the NYSE. It was all that on-the-ground work all over the world. I knew high stakes and high finance from the inside, and not just as a beat reporter.

It was true, and they couldn’t deny it. But that just got them more irritated.

Orders came down from the very top. Constraints were imposed on the subjects I was allowed to write about—even though my non-music articles were very successful.

They would have tattooed jazz critic on my forehead, if I’d let them. Instead I walked away.

I’ve done that a lot in my life. Walking away is NOT always a sign of failure. It’s often a pathway to success.

So you shouldn’t be surprised to see me at Substack. I welcome the freedom it offers. I can finally write about subjects that editors previously prevented me from addressing. As it turns out, these are more widely read than anything I’ve ever written before.

I still write about jazz, and always will—because I love it. But Subtack has allowed me to expand my range. I take full advantage of this freedom. I’m like a sailor on shore leave—I’ll keep causing a ruckus for as long as they let me.

So, yes, I get the last laugh at editors who kept me handcuffed. Which is fine. But, honestly, the system shouldn’t force people into such tight pigeonholes. Part of the crisis in our legacy culture businesses is caused by this enormous resistance to anything that doesn’t fit a formula handed down from head office.

One theory I would have for the above is that you've really resisted this cultural injunction to make yourself a 'brand'—that you seem always to be writing out of the multifarious aspects of yourself and out of a sense of personal integrity, and that people actually really respond to that if they don't exactly know what they're responding to. Is that fair?

I hate the idea of treating people like brands. I even hate treating brands like brands. I always tell CEOs to stop worrying about their brand. If the product or service is good enough, the brand image takes care of itself.

With human beings, it’s even more obvious. A person should never be reduced to a brand. People evolve and grow, while brands are built on stability and predictability. As soon as you turn into a brand, your ability to grow is constrained.

That’s why I admire artists like Miles Davis or Picasso. They refused to repeat themselves. They always sought out new experiences. They didn’t take orders.

I’ve tried to do the same. Every time I’ve made a decision to operate outside my comfort zone, I’ve benefited from the experience—even though it’s often painful at the time. I raised my children to do the same. In fact, I give this advice to everyone.

You've really embraced writing on the internet and in a 'disintermediated' way, and I know (and agree with) all the arguments about why that's the right path to take. How do you react when you come across the anti-Substack pushback, as in the idea that this isn't very serious and is just social media?

Conversely, do you still have voices in your head saying that this is 'self-publishing' and is, like, a lower form? How has the volume of that inner voice modulated since 2010 or so when you started writing online?

When I started publishing on Substack—more than four years ago—I heard lots of complaints about the platform from outsiders. But the people who complained the most eventually joined me on Substack. So I find it hard to take these complaints seriously.

The bottom line is clear. Substack lets writers control their own agenda, and keep most of the money made from it. The authors own their intellectual property, they own their mailing list, they decide what and when to publish. I’ve never enjoyed this kind of freedom before.

The people who spout off their grievances need to show me a better system. And I know they can’t—because they all come to Substack, sooner or later.

Instead of complaining, these critics would do better to find ways of expanding the Substack economic model to other fields. We need something like Substack for music or video or visual art or artisan crafts. That’s a much more worthy pursuit than gripes about Substack.

You've written about making this bold decision to cut ties with traditional publishing. Have you paid some career costs for that? Have you regretted it?

I think you've mentioned that you would like to see a book of Honest Broker essays come out at some point—and it's shocking to me, actually, that nobody has offered to put a book like that together.

My top priority is my Substack, because it’s my own thing—what my Sicilian relatives call la cosa nostra. And I prefer my thing over working for others.

But I hear from NY editors and publishers all the time. I may work with them in the future, but it’s still very difficult adapting to their narrow formulas and constrained worldview.

They still don’t understand that the world has changed. But they will need to learn some new tricks very soon—or they won’t survive. If traditional publishers become flexible and adaptive, I’m more likely to work with them.

Are you religious? Spiritual?

I have the feeling that you have a kind of spiritual system that you've worked out for yourself, but I don't exactly know what it is.

Metaphysics and transcendence are important to my life. They impact my writing—but usually in indirect ways. You won’t get a sermon from me. But that’s okay—sermonizing is not always the most effective method of persuasion.

Here’s the larger truth: My vocation is built entirely on my core values. Let me list some of them: Love, forgiveness, charity, hope, compassion, and….Well, you get the idea.

These are embedded in our great spiritual traditions. But they are also part of everyday life. Or at least they should be.

Some people call this the perennial philosophy or natural law—that’s close to my way of viewing things.

You've talked about a journey from being an “ardent fan of new technology” to viewing “the dominant technologies of the 21st century as manipulative and destructive.” How would you trace out that journey for yourself? What were the flash points along the way that reshaped your perspective?

I lived in Silicon Valley for 25 years. During that period, I had great trust in the tech revolution—I even helped make it happen. But that trust started to erode a few years ago.

Tech got more intrusive and manipulative—and not in a small way. Software got worse. Social media got worse. Search engines got worse. And now AI is getting forced down everybody’s throats, whether we want it or not.

AI might be the tipping point for many of us. But the harm done to youngsters by smartphones is also a huge issue. And let’s not forget digital surveillance or IP robbery or all the other bad things now coming out of Silicon Valley.

I never anticipated writing about these subjects when I launched on Substack. But I haven’t changed—the tech world has changed. Many of the CEOs really did go over to the dark side.

So they deserve to be called out. I’m doing that, but only because it’s the right thing to do.

I mentioned above that my writing is totally driven by my core values. This is a good example of that.

Is the main issue bigness and monopolization—that large companies are always just going to pursue profit for its own sake and that that has an inherently deleterious effect on art and culture, when their profits happen to venture into those fields?

Like, if we have more honest competition will some of the technopolistic problems we're dealing with go away, or is there something in the technology itself that's inherently inimical to human expression?

Why did tech go evil? That’s a big question, and there are many answers.

Heidegger warns us against viewing the world primarily as raw material—and he’s right. The tech agenda must always be balanced with more humanizing forces. I read William Blake as saying the same thing. Shakespeare, too, for that matter.

But let’s look at this situation from a purely economic standpoint. When you do that you see how dangerous it is when users are no longer customers—and are instead turned into products themselves.

Even people now become raw material for tech. Those companies once relied on silicon as their input, but now it’s flesh and blood.

By the way, this is precisely what Heidegger feared—and warned against seventy years ago.

This reification is now the dominant business model on the web. Google or Facebook might have billions of users, but these participants get the service for free—the real customers are advertisers. The rest of us are commoditized.

So the incentives are all wrong. These companies will punish a billion people in order to reward a single advertiser. That’s not how markets are supposed to work.

You don’t need to eliminate capitalism to get rid of this. You just need to change the incentives and stop the abuses—by legislation or litigation, if necessary.

What are your hopes for a ‘creative middle class’? Is that actively developing through a platform like Substack, or are there some insuperable obstacles—the follow-the-leader impulse in human psychology, the 'Pareto principle,' etc, that will always keep art and culture as a star system?

These platforms are mostly about empowering artists and giving them control. This is more salient than their financial impact as “get rich quick” schemes.

Creative careers will never be easy. Substack will create more opportunities—as will other alternative platforms. But I’m cautious about raising expectations too high.

Too many people view Substack as some kind of gold rush. They often point to me as a success story. I’m the miner who struck gold. But it took me fifty years to get to where I am—and along the way, I wrote more than a thousand articles for little or no money.

If I had viewed writing as a money-making scheme, I would have abandoned it decades ago. If I had viewed myself as a miner looking for gold, I’d have shut down the mine in my twenties.

If you do music or writing or painting or any creative pursuit, you must always focus on the intrinsic joy of the experience. It’s a blessing to pursue these vocations. Substack is a great place to experience that blessing.

But if people want to maximize their income, they should probably move to some other platform—Polymarket or eBay or Etsy or Robinhood.

Do you believe that there is such a thing as ‘genius’? What is it? How about '‘talent’?

They exist, but are not easily measured. But that’s okay—all the great things in life resist quantification. You can’t measure love. You can’t measure joy. You can’t measure hope. You can’t measure friendship.

But they are priceless.

Genius is the same thing. It exists, and we need it. But don’t try to put it on a measuring scale. Just be grateful when you encounter it. And try to place yourself in situations where that might happen.

If you’re a young person who wants to pursue a creative career, the single best thing you can do is to find a way of viewing genius from up close.

I think I am completely aligned with you in terms of being deeply hostile to the monopolistic technopoly, and am opting out of the 'AI revolution' kind of no matter where it leads (and have been influenced by you on this decision), while at the same time being very much in favor of digital writing and fiercely partisan about Substack.

For me, this makes perfect sense, but I'm not sure I could put a label on this set of positions—and these stances are often confusing to people who come across them. Do you have a label for your positions here? Or a tidy way to explain it?

I’m not attracted to ideologies. I prefer to operate flexibly, based on my core values. So I need to make it clear that I do NOT hate tech. I do NOT hate business. I do NOT oppose progress.

I merely want all these things to contribute to human flourishing.

I care about people—about their hearts, their souls, their dreams, their aspirations. You can come up with a fancy label for that, and define it as a new worldview. But it’s actually the oldest worldview of them all.

It all boils down to living your life as a decent, kind person. If the CEOs of tech companies hate this, that’s on them. For my part, I’m holding on to the same values that worked for Aristotle or Kant or Dante or Shakespeare and the other wise visionaries of timeless value.

I’m confident their approach will hold up better than the hot tech trends from Palo Alto.

If this were a horse race, I’d tell you to wager on Aristotle, not Zuckerberg. Dante, not Bezos. Shakespeare instead of Musk.

Techies can laugh at that, if they want, but let’s wait and see.

I can completely relate to your first two answers. I can't provide easy answers to those questions, either.

If anyone were to examine my "career," the obvious conclusion he or she would reach is "this boy can't keep a job" and, on the surface, he or she would be correct.

I had to get to be 50 years old before I had enough information to be able to look back and see that, what I was REALLY doing, was picking up one job skill after another. Then, I found what I thought was something that brought all of those skills together.

"This is it!" I thought.

Wrong.

At the age of 64, God revealed to me that my particular collection of job skills and experience meant I had at least one more thing to do with my life.

Now, at the age of 71, I'm not sure what that number of things will be. I'm pretty confident it will be more than one.

And, that's okay with me. I don't believe I will ever retire. That's how much I see before me--which I find exciting. Why would I want to spend the rest of my days at the old folks' home playing shuffleboard and gin rummy?

Like the song says, "The future's so bright I gotta wear shades."

Very interesting and enlightening read! I'm only a little disappointed that the question I submitted wasn't included-"Why does the gentleman artistically depicted in the TED GIOIA header resemble Saddam Hussein surveying the rubble of Iraq outside his window?"