The Day the Police Came to Arrest Me at Stan Getz’s House

And a guide to the magic word you must NEVER ignore

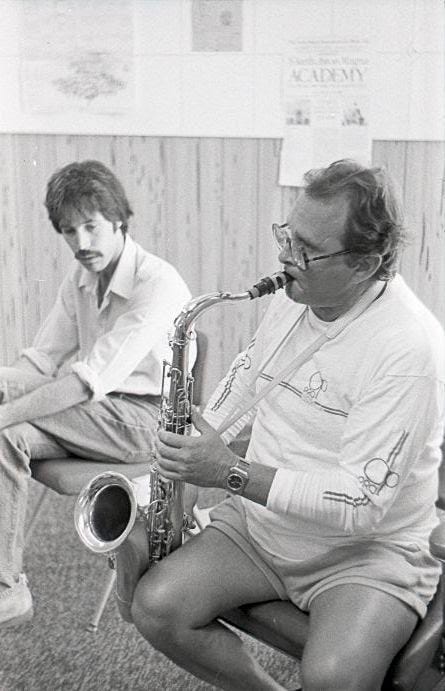

A few weeks after I left graduate school in 1983, I got a phone call from Jim Nadel—who ran the Stanford Jazz Workshop. He asked if I could help Stan Getz prepare for a public lecture he would soon give on the Stanford campus.

I jumped at the opportunity. Stan Getz was a legend and personal hero, and I would have grabbed any chance just to meet him, but now I was asked to help him out.

As it turned out, this meeting led to a lasting connection with Stan—something that hovered back-and-forth between friendship and a professional relationship. For the next several years, I would see him almost daily.

This would be one of the most significant opportunities in my life, and has left a lasting impact on who I am, and what I do.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

My public speaking skills had created this connection. But as it turned out, I was poorly equipped to help Getz—who for all his experiences in front of audiences felt uncomfortable talking to a roomful of college students. (If I can be blunt, I will say that he over-estimated them, and misread what they expected from him.) But this initial project with Getz led to dozens of other situations where I could genuinely help him.

I was no fool. I realized the opportunity at hand, and did everything possible to take full advantage of it. When Stan gave a master class for students, I showed up and volunteered to serve as his accompanist. When he needed a pianist for a charity event, and couldn’t afford to fly his band from New York, I made myself available. When he needed help raising funds to pay for his residency at Stanford and other jazz initiatives, I stared down donors and convinced them to write checks. When he wanted someone to talk through issues and deal with obstacles of any sort, I was there—to this day, the only time I’ve attended an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting was to accompany Stan at his request. (His courage in confronting addiction and the other residual costs of the jazz lifestyle earn my highest praise, and is a side of his life that doesn’t get enough credit.)

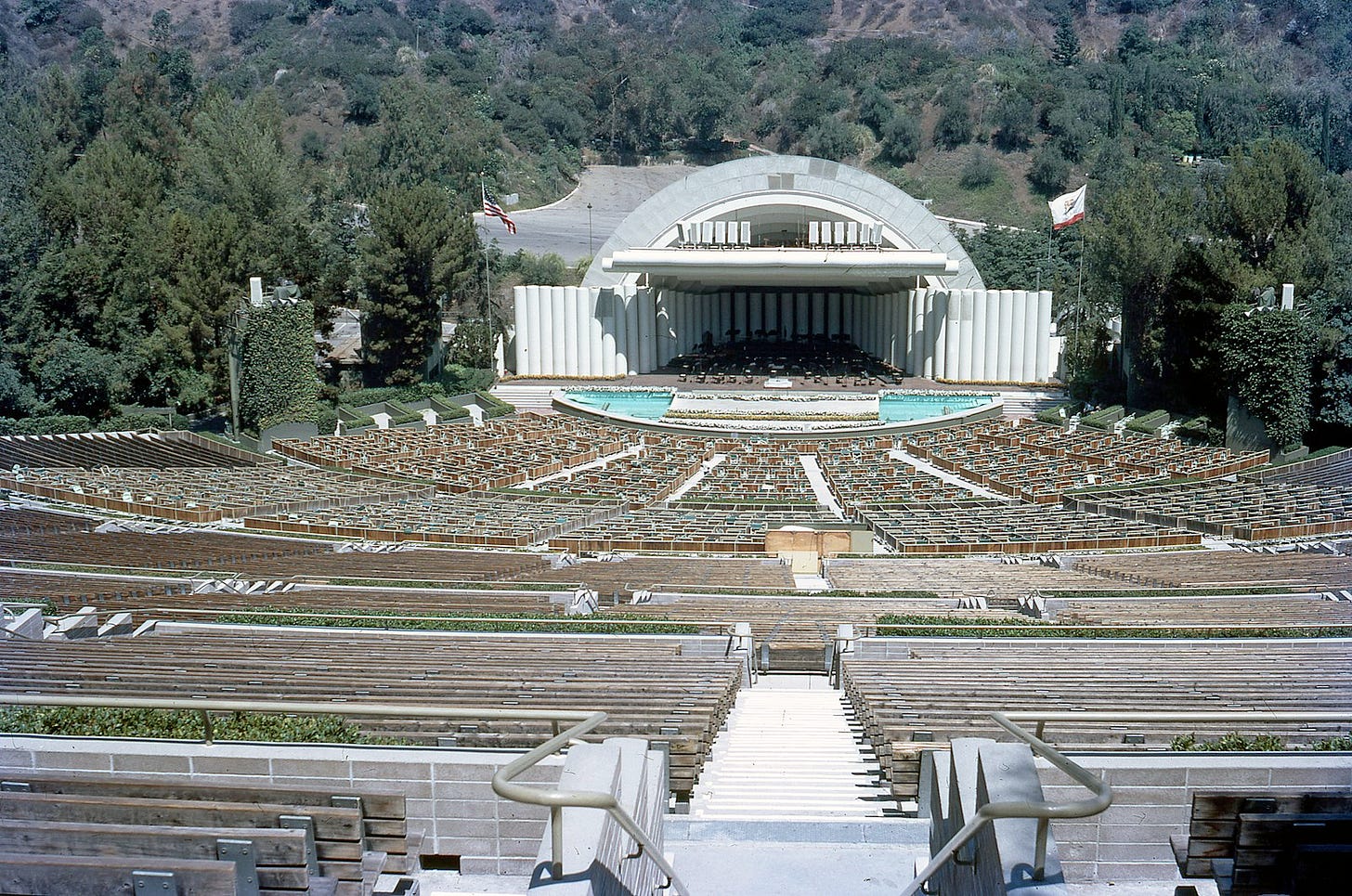

Not every service I offered was glamorous. On one occasion Stan asked me to look after his beloved dog James, because he had to fly to Los Angeles to perform at the Hollywood Bowl.

I agreed, and he gave me the house key.

But he forgot to tell me about the burglar alarm system.

Later that day, I drove to Stan’s house in Menlo Park to look after his dog. I unlocked the door, and went inside. Much to my surprise, I heard a loud beep. (I later realized this was the warning to turn off the alarm—which would blare out at top volume in about thirty seconds.) But I decided to ignore it, and went to the kitchen to get food for the pooch.

But I had barely started on canine meal preparation, when a sound louder than Supersax on steroids started up. This was like the burglar alarm from hell.

Drrrinnngg! Drrrinnngg! Drrrinnngg! Drrrinnngg! . . .

I pride myself on clear thinking in moments of crisis. But, sad to say, I was woefully ignorant of home security systems. As a renter with no possessions a robber would take even if given away for free, (Uh, Mr. Burglar, would you like this copy of Kierkegaard’s Concluding Unscientific Postscript? What the hell, I’ll throw in a paperback edition of Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus as an extra….Wait, wait, don’t run away!), I had no experience with even the most basic properties of burglar alarms.

I wrongly assumed that an alarm would have an on-off switch. I had no idea that they required PIN numbers or passwords. I figured if I could find the source of the ringing, I could simply turn off the alarm.

I jumped into action. I found the speaker that was making all the noise. That was easy. There it was on the living room wall.

There was no switch, but there was a wire coming out of the speaker. With the confidence of Sherlock Holmes on a double dose of opium, I knew that if I followed that wire, I would eventually reach the infernal mechanism controlling the alarm.

So I followed the wire, which ran down the wall to the baseboard into the hall. I had to get down on my hands and knees. And then I followed the wire from the hall into Stan Getz’s bedroom. In the bedroom, the wire went along the wall into his closet.

I was reluctant to dig into the bedroom closet of an illustrious Grammy-winning saxophonist, but I really had no choice. I pushed open the sliding doors, and now could see that the wire was connected to something behind all the clothes on their various hangers.

I was feeling desperation, and started pushing items of apparel hither and thither in a mad quest to get to the back of the closet. But even after shoving aside pants and shirts and suits, and squeezing myself up against the back wall of the closet, I still couldn’t see where this bloody alarm control mechanism was hidden.

So I’m now flailing wildly through all the paraphernalia of a tenor saxophonist’s inner sanctum. And that was when the police showed up.

I didn’t hear them until they were in the bedroom, and right behind me—observing me as I rummaged through Mr. Getz’s intimate belongings.

And then they said the magic word—a single efficacious syllable that I knew from my youth in Hawthorne, California.

Freeze!

AN INTERLUDE ON THE MAGIC WORD

Please forgive me for going off on a tangent here. But for your own good, I need to tell you about this word “Freeze.”

It is truly a magical syllable—even more powerful than its rhyming counterpart PLEASE, which our parents wrongly taught us was the authentic magic word. But I came to learn, growing up in a city where law enforcement officers (according to popular lore) shot first and asked questions later, that the moment you heard FREEZE, you make like Walt Disney in a cryogenic chamber.

I had heard it before, at age 18, when I was a passenger in a car that ran a stop sign in my home town of Hawthorne. Two police officers approached the car, and I made the mistake of reaching into the glove compartment to get the registration papers. That was when one of the officers shouted out the magic word “Freeze.” I could see from the rearview and side mirrors that both cops were pointing loaded guns at my head—one at the back of my neck, and another at the nicely-coiffed 70s sideburn on my right temple.

Yes, they were pointing guns at me merely for being a passenger in a car that didn’t come to a full stop at the sign.

Welcome to Hawthorne, California, the “City of Good Neighbors.”

But I knew the drill, even as a teen. Everybody in my neighborhood knew the drill. When the magic word is spoken, you don’t move a semiquaver— or even a demisemiquaver.

Unless you have seen it in practice on the mean streets, you have no idea of this word’s power. I recall the time a guy grabbed a lady’s handbag in my neighborhood, and took off running like a bat out of hell. He was actually in the middle of a busy street, dodging fast-moving cars as part of his escape route, when a police officer behind him (and out of his visual range), stopped on the sidewalk, pulled out a gun, and pointed it directly at the snatch-and-grab culprit.

In that instant, with firearm pointed, the policeman bellowed out in a deep voice, filled with ominous implication:

FREEEEEEEZE!

That purse-snatcher had been trained well. He may not have gone to Hogwarts, but he knew about magic words too. With the Z in FREEZE still lingering in the air, he FROZE in the middle of that busy street. A moment before he had been running like an Usain Bolt of lightning. But now he was a fossil in amber, forcing the cars to dodge his immobilized body in mid-lane. The purse fell from his otherwise frozen hand, and then, with extraordinary care, he slowly lifted both of his arms above his head.

It was as graceful as a ballet move.

THE INTERLUDE IS OVER

When you have those experiences in your formative years, you never forget them. So when I heard the police officer behind me in Stan Getz’s master bedroom bellowing that incantatory word FREEZE, I didn’t need to be told twice.

I turned into a statue, nothing moving except a few beads of sweat upon the brow. Then, after a moment, I raised my arms—ever so slowly—above my head. Just like the purse snatcher back home.

You can take the boy out of Hawthorne, but you should never take Hawthorne out of the boy.

He might need it some day.

When I turned around, I saw there were two police officers standing there, fully armed. And they had a simple question—what was I doing inside a famous musician’s bedroom, rummaging through his closet?

I may lack a number of practical skills—I’m hopeless at changing the oil of my car, sewing a button on a shirt, etc.—but I do talk a good game. So summoning up all my graduate-degree eloquence, I proceeded to explain. Alas, I was less skilled at getting to the point back then, so my crime scene confession—which could and would be used against me in a court of law, or so I was told—was something along the lines of:

Ah, officer, I know it looks like I’ve been caught with my hand in the proverbial cookie jar. Or in flagrante delicto as the medieval jurists would describe it. But looks can be deceiving. Let me assure you that I’m actually in the process of feeding a dog named James residing on these premises. Now you will ask why feeding a dog requires a close inspection of the inner reaches of a bedroom closet, but if you will just give me a chance to fill in the details. . .

Somehow my words fell short of their intended effect.

These two bulky gentlemen were already envisioning their names in the Peninsula Times-Tribune tomorrow under the headline: “Brave Law Enforcement Officers Arrest Grammy-Nabbing Thief.”

Ah, I had another idea—a longshot and last resort, but just maybe it would work.

I told the officers that I simply needed to call Stan Getz, and he would clear everything up. But how could I possibly reach Stan on the road—all I knew was that he was playing at the Hollywood Bowl.

But back in those days, there were actual telephone operators—real flesh-and-blood people, God bless them, that you could reach instantaneously from any phone and they would help you make a call. My mother had been a telephone operator, working for AT&T for decades, so I had a filial trust in their ability to solve all my problems.

I dialed zero on the phone—which back then put you in touch with an operator. (Does that still work? I have no idea.) A woman’s voice came on the line. “This is the operator, how can I help you?”

“I know this is a longshot, but can you connect me to the phone backstage at Hollywood Bowl. No, no, I don’t want the box office. I need a backstage phone. This is an emergency, and I absolutely must talk to a musician who is performing at the Hollywood Bowl this evening.”

Was there really a phone backstage at Hollywood Bowl? I had no idea, but if not I was in deep doo-doo. And even if there were, would it be possible to get Stan Getz on the phone?

Even now, so many years later, I bless that operator, who simply said: “Just wait one moment.” Then I heard a ringing, and someone picked up on the other end, saying: “This is Hollywood Bowl, backstage.”

It was a miracle, but I reached Stan on the phone. And he spoke to the cops, getting me off the hook. After hanging up, they conferred for a moment, and then reluctantly decided to let me go.

After a few minutes, the alarm stopped by itself. The officers and I parted company, now bosom buddies. I breathed a sigh of relief, and was anxious to get away.

But I did remember to feed the dog.

Ted, I'm cleaning coffee off my monitor screen, thanks to you...I love your insights into music and life, but your comedic timing on the written page is certainly nothing to sneeze at! Also, thanks for a sensitive portrayal of Mr. Getz, a brilliant musician who fought a lot of personal battles throughout his lifetime. Cheers!

Memories! I remember James, I remember your helping Stan with his Master Class q. and a. session, and fear of public speaking in that setting. I treasure those years at Stanford and the times I had with Stan, including an amazing trip to Israel with him. Thank you for sharing this story.