How My Music Got Featured in 'Better Call Saul'

I recorded a solo piano piece in 1986, and it miraculously showed up on a hit TV show this week

A lot of surprising things have happened to me lately, but getting on the hottest show in TV wasn’t on my bingo card. Yet, against all odds, a composition I recorded back in 1986 got showcased on Better Call Saul this week.

People are asking me how I pulled this off. But I didn’t do anything. For the most part it happened without me even aware of what was going on.

Frankly, I didn’t even know the name of the Music Supervisor for Better Call Saul until I looked it up yesterday.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

The story begins back in the mid-1980s, when I was preparing to record my first album, The End of the Open Road. I composed a waltz, languid and bittersweet—but I didn’t know what to do with it.

This was a frequent problem back then. I was a jazz musician preparing to record a jazz album, but the compositions I wrote often didn’t sound very jazzy. The music came to me in moments of inspiration, and it felt right, but it was free-floating and impressionistic, maybe even cinematic—and certainly not something you would play at a jazz club.

I soon had several of these compositions in my repertoire (such as this piece and this other piece)—and I never performed them on the gig. They just weren’t right for a jazz band. But I did play them for my own enjoyment when I was alone at the piano.

And then there was this pastoral composition in 3/4—I called it “A Sunday Waltz.” This is the piece that got featured in Better Call Saul. It was another of my private musical reveries, played solely for myself in secluded moments at the keyboard.

But one day I was visiting Stan Getz, and he was getting a Swedish massage. (This was so typical of Stan—having someone work over his body, almost as if he were a high-level athlete before the big game.) While waiting for the massage to finish, I sat down at the piano he had in his house, and played through my bittersweet waltz.

Afterwards, Stan asked me about that composition. I told him it was my own piece. He responded with a favorable verdict, and then said something that amazed me. “You should bring a whole rhythm section over to my house some time and we can play some of these songs.”

You might be surprised to learn that I never followed up on this invitation. I never even considered doing it. The idea of just showing up at the Getz residence with a band and enlisting the tenor sax master to play my tunes seemed like the height of presumption.

But he liked my compositions, especially that waltz.

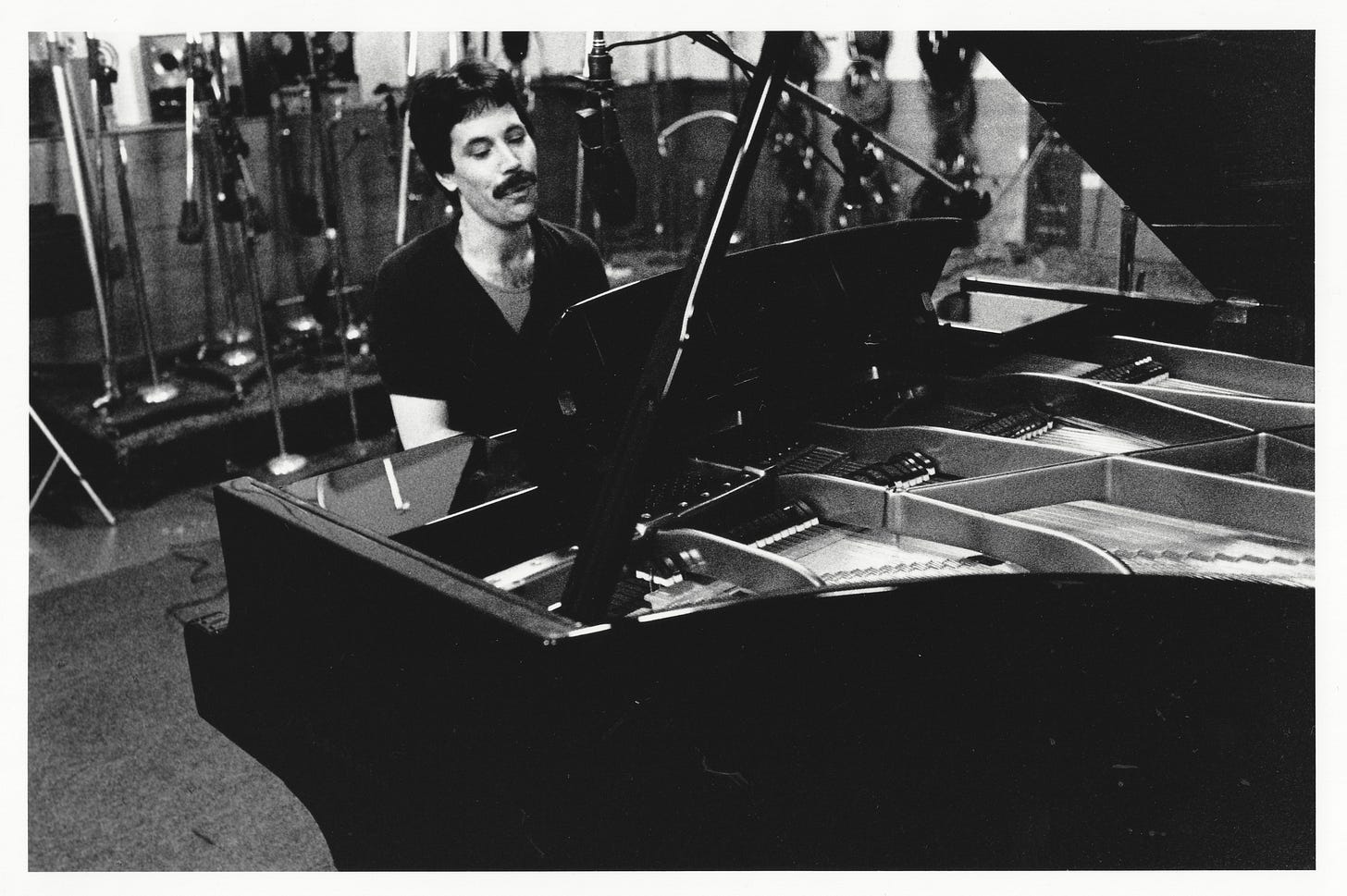

So when I finally made my record at the Music Annex in Menlo Park, I still had a little bit of studio time left after the rest of the band went home. I decided that I might as well record some of these solo piano vignettes—what’s the downside?

It helped that I liked the piano—the sounds it made just lingered in the air, even with very little pedaling. That may not have been good for bebop, but it was perfect for my solo piano pieces. And the engineer Russell Bond knew exactly how to record the instrument.

So we ran the tape—yes, we still used tape in those days—and entering that trance-like state I find conducive to the best music-making, I played my moody waltz.

Here’s the track I made that day.

Many people who heard the recording responded positively to these solo piano pieces. A number of them told me I sounded like Vince Guaraldi—I can’t tell you how often I heard that comment. It was a comparison I didn’t earn or deserve—and it wasn’t really aligned with the grittier image I had of myself as a jazz musician. I saw myself operating more in an Ahmad Jamal or Denny Zeitlin vein. And, if I can be frank, nothing would have destroyed my jazz street cred faster than working from the Charlie Brown playbook.

But I now understand that the cinematic quality of my music was what elicited that response. In any event, I always replied in the same way: “Thank you. I don’t have Vince’s talent—but I would definitely settle for a tiny share of his record sales.”

But the bottom line was that this was music without a legit genre category. It didn’t fit with my jazz career and self-image, and just wouldn’t work on jazz radio formats or in nightclubs. Maybe if I was writing soundtrack music like Guaraldi, I could find a place for it, but not in the career I was pursuing back then.

So I forgot about my waltz.

It was easy enough to do. I had so much happening in my life back then (and still do), that it’s almost a relief to put some things on the back burner. I gradually became so busy with my writing projects, that I couldn’t find time to market myself as a composer and pianist—especially after my battles with arthritis.

Even when those symptoms went away, I viewed piano playing with caution and restraint. I didn’t want the pain in my hands to come back, so piano playing no longer was a career, merely something I did for my own enjoyment. I was okay with that—although I really didn’t have much of a choice.

And it all should have ended there. But somehow I still had some fans who remembered my piano music.

A few years ago, an overseas distributor inquired about selling my album The End of the Open Road in Japan. At that stage, I didn’t even know who owned the rights to the recording.

The original label had been acquired by a larger company. And then ownership changed hands again—through a bankruptcy proceeding, or so I heard. Eventually the masters got combined with another catalog of recordings made by the famous producer Bob Shad. But Shad had died decades ago, and ownership transferred to his daughter Tamara Shad, who passed away in 2008.

I knew none of these individuals. Never met with them. Never spoke with them. I didn’t even have a phone number or email address. So it took a huge amount of footwork and sleuthing on my part just to find out how to sell my records in Japan.

But I finally worked my way through this maze, got the proper permissions, and shipped off a bunch of albums to Tokyo.

And this is when I got a lucky break.

In the course of working through these arrangements, I came in contact with Bob Shad’s granddaughter Mia Apatow—who liked my music, and saw potential in these old recordings I’d never seen myself.

She thought they could work in TV and film. And in a strange sort of way, that made sense to me. I always composed music that felt like part of my own personal soundtrack. So why shouldn’t this music work on the screen?

Even so, when Mia told me that my waltz was in consideration for a scene in Better Call Saul, I didn’t believe it. Last week she said that it was official, a done deal—but I was still in denial.

I have a motto I live by. I even taught it to my sons: “Don’t believe anything you hear, and only half of what you see.”

That guidance has held me in good stead over the years. Most of the deals presented to me as a freelancer never pan out, and I have lowered my expectations accordingly. Hey, that’s life in the current day—at least for folks like me.

So even after the TV placement was approved and ready to go, I still didn’t think it was real. But on Monday night, I sat down in front of the TV, and watched episode nine of the final season of Better Call Saul.

And there it was—my song from 1986.

Around the 26 minute mark, character Gus Fring goes into an elegant southwestern restaurant bar, and in the background you can hear my waltz—and it continues for an entire minute.

That’s about 60 seconds more than I anticipated.

My son Thomas, who watched the episode with me, insists that Gus even glanced approvingly at the piano player during that scene. I didn’t notice that detail—I was too busy looking at my stopwatch to gauge how much screen time I was getting. But if it’s true, I’m gratified—it’s not easy to please a drug underworld kingpin.

But where do things go from here?

Probably nowhere. I don’t really have a plan for my vocation as a pianist and composer. Others who receive TV placement at this level, would parlay it into something else—but I’m just happy to enjoy the moment.

If there’s a lesson here, it’s that I never did anything in my life to fit into a current trend, and always aimed to do work that would hold up over the long term. And that seems to have worked out, both in my writing and music, and other spheres of my life as well.

Even so, I never thought a song I played during an extra hour of studio time in 1986 would reach millions of people 36 years later. Maybe I should find time to record some of the other solo piano pieces I’ve got sitting around.

They even listed you by name in the Closed Captions. That’s definitely not a given when music is played.

A very beautiful song! May the royalties flow freely!