How Musicians Invented Stand-Up Comedy

Even today rhythm makes a joke funnier

I often make grand claims about the importance of music. But I work hard to back them up.

So people laugh when I tell them that musicians created the legal system. And they’re skeptical when I assert how music plays a decisive role in advancing human rights and civil liberties. But when they see the evidence, they start to grasp how powerful songs actually are.

Today I want to take on a lighter task. I will show how musicians invented standup comedy.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

In fact, the very first reference to standup comic comes from a write-up about singer Nellie Perrier. She was described in The Stage (1911) as performing “stand-up comic ditties in a chic and charming manner.”

But these humorous songs had flourished throughout Britain (and elsewhere) long before that time. Back in 1865, there were 32 music halls in London alone, some seating thousands of patrons. Here comic songs served as an important draw, but the same thing happened in highbrow settings. If you’ve seen a performance of any Gilbert & Sullivan operetta, you know how much audiences love the humorous patter songs—they are much like standup comedy routines set to a jaunty melody.

The star singer in a Gilbert & Sullivan production—Martyn Green, Peter Pratt, John Reed, etc.—is even called the “principal comedian.” They are skilled singers, especially good at enunciating each syllable at lightning speed. But audiences don’t buy tickets to hear their vocal pyrotechnics.

I attended many performances by Reed in my youth (and impertinently asked him for his autograph again and again, on more than a half dozen different occasions—he always obliged graciously). But I never heard anybody refer to him as the lead baritone. Reed knew—as the lyric he sang in The Yeomen of the Guard specifies—that he was “paid to be funny.”

In those days, a comedian almost always was a singer. You would often see their faces on the published sheet music.

We find the same thing in America, but in a more degraded form. The word minstrel, for example, as applied to a minstrel show, always encompassed both song and comedy. But genuine African-American comedians soon emerged, and they too relied heavily on their musical abilities.

Bert Williams provides a fascinating case study.

Williams, born in the Bahamas in 1874, was the biggest-selling African-American recording artist in the years before the rise of blues and jazz. And he achieved this with a deft combination of music and comedy—which he demonstrated on Broadway and in film. His signature song “Nobody” (1905) sold more than 100,000 copies.

Williams’ recordings demonstrate his skill in moving effortlessly from talking to singing—and often lingering between the two, with a semi-sung comic delivery. You might say he anticipated rap. But he also laid the foundation for modern stand-up comedy, pushing beyond the confines of song but still relying on its rhythmic patterning.

Or consider the case of vaudeville entertainer Bill Higgins, who started out as a singer in his hometown of Columbia, South Carolina before touring in comic music revues. He later teamed up with Billy King, another African-American comedian, whose traveling show helped launch Walter Page’s Blue Devils, which morphed into the Count Basie jazz orchestra.

Today, it’s hard for us to imagine a comedian playing a key role in the evolution of jazz. But that wasn’t such a far-fetched notion back in the 1920s and 1930s. Or even into the 1940s and 1950s—when Slim Gaillard, Harry the Hipster Gibson, Lenny Bruce, and Lord Buckley (among others) all had strong ties to modern jazz. You might even say that bebop helped lay the foundation for edgy comedy—the performers certainly exchanged ideas, and shared the same stages at the same nightclubs.

The connection between jazz and comedy is mostly forgotten now, but not entirely dead. I’ve even played comedy clubs in my music career, backing up standup acts with choice jazzy bits of music—and I’m hardly the only jazz cat to take these lowly gigs, although most pros will leave them off their CV nowadays.

(Somebody should write a book about jazz musicians playing at comedy clubs, strip clubs, circuses, auctions, and other unlikely venues. These gigs were more common than fans today realize.)

Many 19th and early 20th century comedic songs in America originated in (or were influenced by) minstrel shows. But this was a degraded version of the original minstrel tradition, which is thousands of years old. The first minstrels were traveling music entertainers, and a major cultural force in medieval Europe.

These minstrels were extremely versatile—and might engage in everything from juggling to dramatic performances. But music and comedy were especially popular, and drew audiences wherever they journeyed.

But few of their songs have survived. The Church was not receptive to secular songs of any sort, and bawdy humor was a special target for criticism and censorship. But a handful of humorous medieval documents were somehow preserved, and offer insights into the close connection between comedy and musical entertainment.

The Carmina Burana, now famous as inspiration for a musical work by Carl Orff, is a collection of these songs, most of them dating back to the 11th or 12th century. The secular music from this era is almost entirely anonymous, or attributed to historical figures with vague biographies—such as the Archpoet, one of the greatest comedic talents of the medieval era, but surrounded by a deep cloud of mystery.

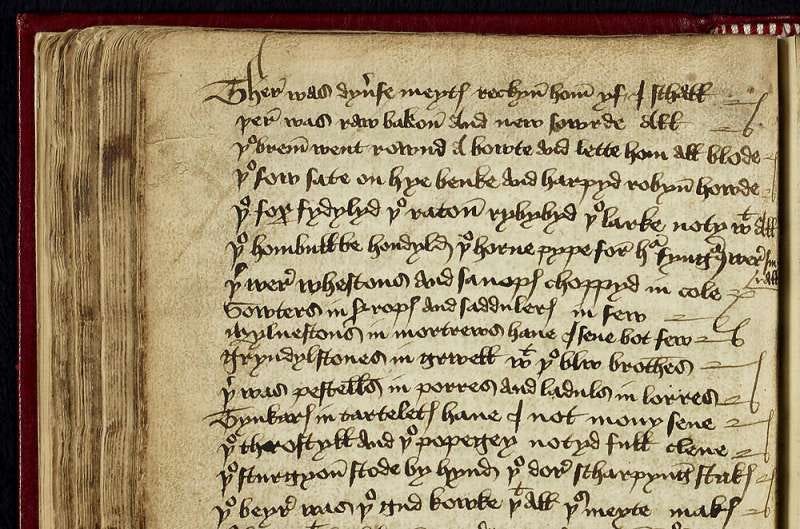

The 15th century Heege manuscript is a fairly late example of this tradition, but also a significant document in the history of comedy. Some have even described it as a forerunner of Monty Python. But the reality is much simpler—this is just a surviving script used by a typical traveling performer.

I could dig back even deeper in time, but the details are harder to pin down. There’s good reason to believe that traveling musicians were singing comic songs in ancient times. And, of course, ancient Greek comedies involved singing, but we have little reliable information on the musical accompaniment.

Frankly, I don’t think there was ever a large society that didn’t combine music and humor. Eventually those two traditions went their separate ways—with comedy turning into a (mostly) spoken idiom. But the separation was never complete.

Even today people associate the clichéd drum rimshot with the punchline of a joke. Rhythm really does make a joke funnier.

In the middle decades of the 20th century, the comic song tradition got a boost from movies and Broadway. But the linkages started to fray during the 1960s. Yet even at that late date, a few comic singers found an enthusiastic mainstream audience. Tom Lehrer was legitimately as funny as any standup comedian of the era—and his works hold up quite well today. Or consider the successes of Alan Sherman or Ray Stevens. Monty Python, mentioned above, also relied heavily on songs, with a heavy dose of absurdism, and many are very amusing.

And today?

The champion of the comic song in the 21st century is Weird Al Yankovic. He hasn’t released an album since 2014, but the enthusiastic response to that record—which made its debut at the top of the Billboard chart—suggests that the days of the comic song are not yet over.

And, of course, we also have short funny TikTok videos that rely on music. Those probably shouldn’t even be mentioned in the same article as Gilbert & Sullivan. But they show how hungry audiences still are for musical comedy.

Some people tell me that Weird Al would have a hard time starting out today. Judging by box office receipts, comedies of any sort are struggling to find a mainstream audience. And, of course, many of the gags of the past are considered offensive nowadays. But even more to the point, Yankovic relied on a steady stream of familiar new songs that were suitable for parody. Alas, the fragmentation of our music culture and the declining audience interest in new music of all sorts makes that a harder proposition.

But I remain optimistic. Everything happens in cycles, and comedy will inevitably return to the forefront of our culture. The comic song is a perfect way to make that happen. After all, this tradition of musical humor has lasted thousands of years and has survived all sorts of censorship and backlash in the past.

I suspect that, even now, audiences are waiting for something of this sort. People really do want to laugh, even (or especially) in challenging times. When that happens, musicians will have every right to play a key role in reviving a more lighthearted culture where comedy plays a prominent role—if only because they helped invent it in the first place.

Ted you're right that we leave the comic backup gigs off our bios .But now I'm thinking I should add that I played with Joan Rivers, Dangerfield, Rickles et. al.! The best part was that they were much funnier and raunchier live than they were allowed to be on TV.

And I agree that our comedic culture owes far more to the Vaudeville tradition than is rightly acknowledged. I've always admired the stars of yesteryear who could sing, dance, play instruments and do comedy. I suppose it was easier to keep all those skills sharp when you had a steady gig for 6 months, then it was held over for another two. They worked hard though--several shows per day!

Maybe stand up is the last thing AI will be able to take over from humans. After all, Timing can't be programmed --it can only be felt.

Ted...no doubt you'll find it interesting. https://datacolada.org/2