How I Take Notes

In response to reader requests, I share my 3 levels of note-taking

Let me tell you what good note-taking can do.

When I was a college student, I had to compete in a wine-tasting contest. But I was at a total disadvantage.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

I hadn’t even reached legal drinking age, and knew almost nothing about wine—but that was only a small part of the problem. Even worse, the other participants had tasted these same wines the previous week, but I hadn’t been there. And now we all had to identify the same vintages in a blind test.

So I had no chance of winning the contest—I’d merely be guessing.

But at the last minute, one of the other contestants gave me his tasting notes from the previous session. He had written down his subjective impressions of each wine.

“Maybe you can identify the wines based on my descriptions,” he suggested.

I laughed at this notion. But then I looked at his notes, which were richly detailed and even brutally poetic.

They were something along the lines of:

This blustery white smells like the back room at the local dry cleaning shop. I keep hoping for even a hint of sweetness, but somebody must have ordered this wine on hangers with extra starch.

Or:

This leathery red just walked through a flower garden. But you only get a quick sniff of tulips and daffodils, and more shoe sweat than either. The aftertaste vanishes faster than a purse-snatcher on roller skates. So drink this vintage quickly—and remember to pinch your nose first.

Etc. etc.

As you may have guessed, we weren’t drinking the best wines back then. But these notes did give me something to work on as I tried to identify the vintages.

And can you guess what happened?

I won the contest that evening. I had never tasted any of the wines before. But I successfully matched them based on the tasting notes alone.

I was reminded of this recently after I wrote about my lifetime reading plan, and several people asked me how I took notes.

That’s because my wine-tasting victory at age 18 changed my views on how to do this. This was when I first started to view note-taking as a major factor in my personal development.

At this juncture, I completely changed how I took notes in my lecture classes.

I taught myself how to write down everything in coherent complete sentences and integrated paragraphs. I learned how to do this in real time while the professor was speaking.

This forced me to improve my listening skills, because I was always looking for connections and coherence in what I heard. And it also helped my thinking and writing skills too.

The discipline of taking notes can evolve into taking notice—which is a much higher level activity.

I never reached the expressive level of “someone must have ordered this wine on hangers with extra starch.” But still, by sheer diligence and focus, I found that I could create something on the spot that was holistic, factual, and possessed narrative coherence.

I would walk out of each lecture with several handwritten pages that were almost an essay. It was a summary I could return to a month later or years later, and understand what had transpired in the classroom that day.

I retained that skill even after I finished my formal education. When I read books, I would apply this same approach of taking notes in complete sentences and coherent paragraphs.

And if I found a passage that was especially illuminating, I copied it out by hand.

But I gradually learned that there was an even higher level of note-taking.

Or put differently, I eventually decided that there were three kinds of note-taking, and that I needed to use all of them.

(1) MARKING UP THE BOOK: I’ve always had too much reverence for books, and want to keep them pristine. But to get the full benefit of reading, I have to mark them up. I need to underline key passages. I have to add comments in the margins. Sometimes I even insert post-its or cut out reviews of the book from the newspaper and fold them into the pages.

The very process of doing this makes me a more attentive reader. As I read, I am constantly on the lookout for key passages or larger connections or surprising statements. But the greater benefit happens later—when I return to that book months or years after I read it. Now my markings allow me to re-experience all my initial impressions.

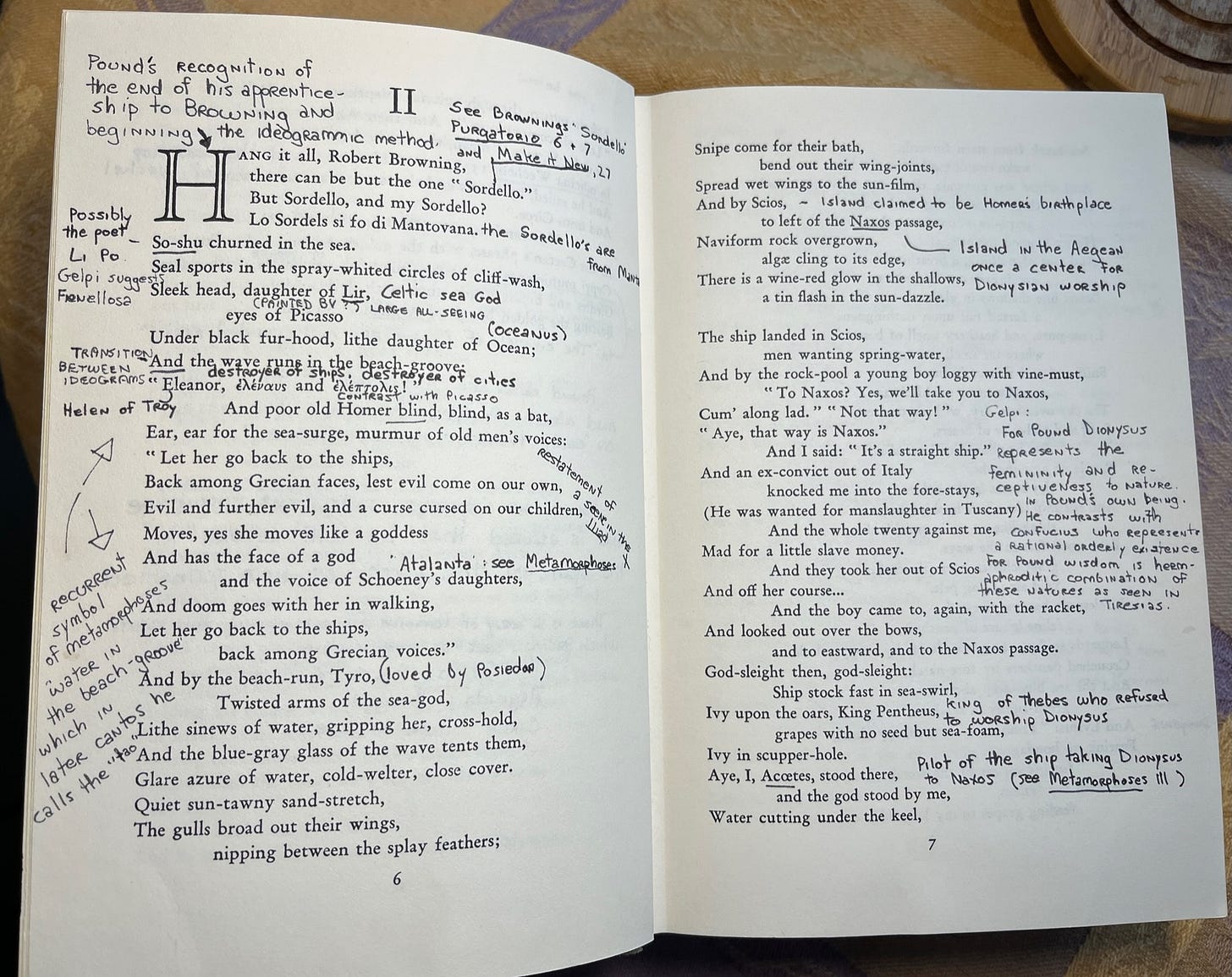

In the aftermath of my wine-tasting triumph, I started taking more ambitious notes in the margins of my books. Below are some examples from a few months after that contest—these notes come from my student copy of Ezra Pound’s Cantos.

I wrote these marginal notes when I was a teenager, but I can pick up this book today and still understand exactly what I was trying to convey back then.

Or here:

I didn’t always do this, however—and I regret it now. I didn’t deface my books enough. I should have marked them up even more. Sometimes I’d just scrawl a question mark or exclamation point in the margin, without any commentary.

I can’t take all the blame, however. Because there is only so much room in the margin of a book. That’s why I also needed to do more, specifically…

(2) SUMMARIZING THE BOOK: When I finish a book, the temptation is to start another one. (Don’t laugh, that’s what temptation looks like in my placid life.) But it’s useful to spend a couple more hours writing a brief summary of the book. That helps me mentally process what I’ve learned, and also serves as a useful guide later when I want to revisit the subject.

But I eventually learned that even this is not sufficient. That’s because there’s a third stage of note-taking—which everybody should learn. And it’s absolutely essential if you’re a writer. Namely…

(3) WRITING DOWN MY OWN IDEAS THAT THE BOOK SPURRED: I didn’t start doing this with any consistency until I was approaching middle age. But this is the most powerful kind of note-taking of them all.

By doing this, I expand my own thinking by leaps and bounds. Often the notes I write in this manner serve as the building blocks for my own articles and books. But even if I wasn’t a writer, I would benefit from this—because the greatest reward from reading is in the ways it improves and broadens you as the reader.

In other words, I took notes when I was younger in order to learn. But I now take notes in order to enhance my own ways of engaging with the world.

For example, below are screenshots of some notes I took around ten years ago—chosen randomly from my files. I have hundreds of examples like this, and most of them (as in this instance) never lead to anything publishable. But I still take great care in this. You can see how I am trying to analyze, compare, and add my own perspectives. And, just as I tried to do back in college, I still aim to make everything a coherent and flowing narrative—even if it’s just my reading notes.

Of course, this also increases my productivity as a writer.

For example, some of you may have wondered about a special section of The Honest Broker called The Vault. This includes more than 400 literary essays that I’ve written over the years. The vast majority of these were simply the result of me thinking about books I’d read, and trying to organize my observations after I’d finished them.

Nobody hired me to write these. Nobody even suggested that I do it. I wrote them for my own benefit, as an extension of my note taking. I later published hundreds of them online, but they would have served an important purpose for me even if I’d never taken that final step.

This is an obvious example of how the discipline of taking notes can evolve into taking notice—which is a much higher level activity.

I only wish I had started taking these higher level notes at a younger age. My notes on what I read in my 40s and 50s are so much more useful than those from my 20s and 30s.

But, hey, better late than never.

Perhaps all this seems too intense for you. I’ll admit that my vocation requires me to pay close attention to books. Hence, you might think that this note-taking method is irrelevant for most people.

Let me respond to that with three observations:

Even when I did work outside of music and writing, I still benefited from this approach. There was a time in my life when I earned a paycheck doing very hands-on work (much of it overseas) that bears no resemblance to what I do today. But I still took careful notes of what I learned from the Far Eastern Economic Review, Harvard Business Review, The Economist, McKinsey Quarterly, etc.—which provided me with a constant flow of information and ideas I could use back then—and I would have done something similar if I had pursued a vocation as a scientist or a cook or whatever. The simple fact is that there is no job or career in which keeping track of your learning isn’t useful.

I often took notes that, at the time, seemed totally useless, but they later proved extremely useful. Sometimes 10 or 20 years elapsed before I could benefit from them. So I’ve learned never to assume that a book I’ve read can’t have future value for me. And that’s why I’m skeptical when others tell me that note-taking is irrelevant in their situation. Can they really know this? My considered judgment, based on a lifetime of active learning, is that we seldom understand the full benefit of high level reading until long after the fact.

Finally, note-taking is useful as a source of discipline and mental training—and that’s true no matter what the subject is. Even learning to write down a coherent summary and assessment of a lousy TV show or second-rate movie can have value. In a strange way, I’ve learned almost as much from inferior works as I have from superior ones.

So don’t dismiss my approach to note-taking as an extreme measure suitable only for obsessive types. Yeah, I am an obsessive type. But even in smaller doses, this heightened degree of engagement with the written word can have a transformative impact on your life.

Every day I write down a few quotes from something I read that stood out for me. I also write down 7 things I saw or noticed during the day. I also write down, in narrative form as you mention, the things memorable from that day. These are my ways of actively engaging with the material of my life. Thank you for your newsletter. I'm glad I'm not the only person who writes notes and marginalia...😊

Note-taking should be its own subject in schools. As your piece implies, taking notes is just another way of saying "critical thinking" and it is a skill that so many of us lack.