How Do You Celebrate Truman Capote's 100th Birthday?

Today is his centenary, but is Capote a hero or just an embarrassment?

Writers dream of lasting fame, but even successful authors are typically forgotten long before their centenary.

Here are some Pulitzer Prize winners in fiction from the 1920s and 1930s. How many have you read? How many names do you even recognize?

Julia Peterkin (1929 winner for Scarlet Sister Mary)

Oliver La Farge (1930 winner for Laughing Boy)

Margaret Ayer Barnes (1931 winner for Years of Grace)

T. S. Stribling (1933 winner for The Store)

Caroline Miller (1934 winner for Lamb in His Bosom)

Josephine Johnson (1935 winner for Now in November)

Harold L. Davis (1936 winner for Honey in the Horn)

According to Amazon, none of these award-winning novels now ranks even in the top 250,000 in it sales rankings.

If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

By my measure, few pop culture reputations last more than about 80 years, even for superstars. Go ask people under the age of 30 to identify Bob Hope, Doris Day, Clark Gable, Mae West, Glenn Miller, Jean Harlow, or other legends from pre-1950, and look at their blank stares.

And writers fade from view even faster. In 2010, I shared my enthusiasm for novelist John Fowles on his centenary—but nobody else paid much attention to the milestone. Fowles enjoyed awards, bestsellers, movie deals—and deserved them all. But he’s barely remembered nowadays, except by a few gray-haired readers.

Five years later, I did the same for Fritz Leiber, who is a deserving pop culture hero—his concepts have been robbed wholesale by countless video game developers, fantasy fiction authors, Hollywood scriptwriters, and graphic novelists.

But Leiber found himself out of favor long before he died—a fan visited him in the late 1970s and found this influential storyteller living in a tiny single room in a seedy San Francisco hotel. Others got rich on the fruits of his imagination (and still do), but Leiber had to prop up his typewriter on top of his sink in order to churn out another story—and pay another bill.

This is the fate of so many grand authors. Next year will mark the centenary of William Styron, John Hawkes, and Gore Vidal—all heralded as literary superstars in their day. But don’t count on fireworks and celebrations. Fame is fleeting, especially for those who build their empires on paper.

And now we come to Truman Capote, who was born exactly 100 years ago today. Somehow he’s hotter than ever.

A few weeks ago, I watched the latest season of the TV series Feud—and it was devoted entirely to Truman Capote, and his cantankerous high society friendships. Tom Hollander earned an Emmy nomination for his performance as Capote.

But even this acclaimed depiction fell short of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s uncanny acting in the film Capote—which earned him an Academy Award, a Golden Globe, and a long list of other honors.

And just a year after Capote (the film), Toby Jones played the author in Infamous. Capote also shows up in documentaries (The Capote Tapes, Truman and Tennesse, The Tiny Terror), and onstage (WarholCapote, Tru), and in a variety of podcasts.

We just can’t get enough of him.

In fact, the entire true crime genre of podcasts—intensely popular nowadays—relies heavily on journalistic techniques Capote demonstrated in his most famous book, In Cold Blood (1966). I might even go further, and laud Capote as the progenitor of reality TV, which at its best represents an onscreen realization of Capote’s non-fiction novel—heightening reality through the techniques of storytelling.

“He knew John F. Kennedy, but also knew Lee Harvey Oswald. He knew Robert Kennedy, and also knew Sirhan Sirhan. He knew Charles Manson, but also four of Manson’s victims.”

But in some ways, those achievements are beside the point. Truman Capote is still a huge pop culture figure after 100 years—but not because of his writing. Make no mistake, his books are outstanding. But Capote gets the Hollywood treatment today because of his larger-than-life personality.

He was a character, and stood out from the crowd everywhere he went. Even at the peak of his fame as an author, Capote was known to millions of people who never read contemporary fiction from his TV appearances.

Sometimes he was exceptionally articulate and insightful as a talk show guest.

But just as often he was embarrassing or outrageous.

He could be catty or cantankerous or controversial, but Capote was never boring.

That was true even before he became famous. Wherever he went, Truman Capote stood out from the crowd—even at just five feet, three inches.

“In his teens, Capote served for a time as an office boy on The New Yorker,” Brendan Gill recalls in his book Here at the New Yorker. “Capote dressed with an eccentricity that wasn’t to become a commonplace among the young for another twenty-five years; I recall him sweeping through the corridors of the magazine in a black opera cape, his long golden hair falling to his shoulders: an apparition that put one in mind of Oscar Wilde in Nevada, in his velvets and lillies.”

“Before the first week was out, he was one of the chief topics of hallway conversation,” notes biographer Gerald Clarke. “Two of the elevator men were so confused that they bet a dollar on his gender.”

Editor Leo Lerman thought Capote looked like an elf, not a human being. According to magazine head William Shawn, Truman Capote was “almost like a child.”

He didn’t last long at The New Yorker. Setting the pattern for his future career, Capote made high powered enemies—and was forced to leave after insulting Robert Frost. If Capote had any regrets, he never admitted them.

Even as a child, Tru knew how to make the right friends. His nextdoor neighbor and confidante in Monroeville, Alabama was Harper Lee—future author of To Kill a Mockingbird. The odds against two famous writers showing up on the same street in this small town in nowheresville (population around one thousand souls back then) seems incalculable.

But Truman Capote always knew famous people—and often long before they were famous. I’ll go further, and claim that nobody in the twentieth century had more direct experience of the human condition than Truman Capote. Does that sound like an extreme claim? But just consider—Capote knew everybody at The New Yorker, but he also knew more than 400 people who had committed multiple murders.

He knew John F. Kennedy, but also knew Lee Harvey Oswald. (Only two people in the world could make that claim.) He knew Robert Kennedy, and also knew Sirhan Sirhan. He knew Charles Manson, but also four of Manson’s murder victims.

He laughed at Norman Mailer for writing a book on Marilyn Monroe, although Mailer had never met her (but Capote had, even before she became a star). He also mocked Mailer for writing a thousand-page book on murderer Gary Gilmore without ever having met the man. Capote could fill up an entire Black-and-White Ball with famous killers he had known.

Capote had seen it all—in Hollywood, in New York, in Europe, in Russia, and on Death Row. And when he met people, he could get them to talk. He was so good at this that people feared him.

When he traveled to Japan to interview Marlon Brando, who was there shooting Sayonara, director Josh Logan banned Capote from the film set. Logan did everything possible to stop the interview—he knew how dangerous this writer could be. But all his efforts at damage control failed. Capote charmed his way into a private dinner at Brando’s hotel suite. By the time the night was over, Tru had material for a Brando profile so revealing that the actor avoided journalists from that point on.

I can’t think of another writer who made so many famous friends—and enemies. In the course of the 200 pages of Conversations with Capote, interviewer Lawrence Grobel asks him about numerous celebrities. And Capote almost always responds with a personal anecdote.

In passing, during the course of his dialogues, he describes:

Dining with Elvis Presley;

Dropping acid with Cary Grant and Aldous Huxley;

Getting stalked by a teenage Andy Warhol

Hanging out with the Rolling Stones (“Mick is a bore”);

Socializing with John Lennon (“I liked him a lot” but Yoko Ono is “the most unpleasant person that ever was”);

Beating Humphrey Bogart in an arm-wrestling match;

Hobnobbing with first ladies (he knew at least six, starting with Eleanor Roosevelt);

Encountering Johnny Carson in a malicious rage at his doorstep;

Vacationing with Adlai Stevenson;

Watching Kabuki theater in Japan with Yukio Mishima;

Making introductions for James Baldwin;

Sharing witticisms with his friend Greta Garbo (despite her reputation for solitude);

Socializing with every member of the Supreme Court (“I’ve met them all”);

Collaborating with Albert Camus;

Visiting Charlie Chaplin in Switzerland;

And the list goes on and on….

It’s easy to forget the writing amid all this networking and name-dropping. But Capote was the real deal, one of the great storytellers and prose stylists of the 20th century. Yet all that prodigious talent at the typewriter is almost forgotten nowadays in the current obsession with Capote as bon vivant and tattler of celebrity gossip.

That’s a shame, because the real place to enjoy Mr. Capote’s genius is on the printed page, not the movie theater or TV screen.

“I started writing when I was eight,” he later recalled. “As certain young people practice the piano or the violin, four or five hours a day, so I played with my papers and pens.”

I’m a firm believer in the “ten thousand hours rule,” which asserts that mastery of any advanced craft requires a huge investment of time—amounting to three hours per day over the course of a decade, more or less.

That’s roughly the time I spent at the piano before I could make jazz recordings of any merit. And many other examples confirm the ten thousand hours rule, from the Beatles gigging in Germany to Bill Gates fiddling around with computers. But Capote may serve as our single best example from the world of writing.

Surviving stories from elementary school (kept by a teacher) show a significant leap from sixth grade to eighth grade. By age thirteen, one of his stories was so impressive that teachers passed it around, and even suspected plagiarism. “By the time I was seventeen I was an accomplished writer,” Capote boasted—and with good reason.

“I prefer to underwrite. Simple, clear as a country creek.”

His short story “Miriam,” published in Mademoiselle when Capote was just twenty, already demonstrates the clarity and tautness of his prose style. Herschel Brickell, editor of the O’Henry Award prize-winning stories, was so impressed that he declared that this “young man from New Orleans just past his majority” was “the most remarkable new talent of the year.”

Capote could have made his reputation entirely on his short stories. The best of them, especially “A Christmas Memory,” are role models in concise, impactful storytelling. Unlike other authors, who need many pages to achieve their special effects, Capote works wonders with just a few words.

“I think most writers, even the best, overwrite,” Capote later explained in the introduction to Music for Chameleons. “I prefer to underwrite. Simple, clear as a country creek.” And that last sentence actually demonstrates his strength—in just six words, Capote both sets his standard, and achieves it:

Simple, clear as a country creek.

Once you’ve read writing of that sort, you start wondering why everybody else needs so much verbiage, so many pages.

But our young author was too ambitious to stick with short stories, and parlayed his early acclaim into a contract to publish a novel with Random House. The resulting book, Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948) is an accomplished work, but still under the spell of Capote’s Southern gothic influences.

Yet it tells you a lot about Capote that the most talked about part of this debut novel was the back cover photo of the author. His reclining posture and come hither gaze made it immediately clear that this young writer was a scandal waiting to happen.

Capote continued to improve with each new book, demonstrating his novel-writing prowess with The Grass Harp from 1952 (his personal favorite) and Breakfast at Tiffany’s from 1958. But his talents were also in demand on Broadway and in Hollywood. He even contributed lyrics to a respected jazz standard, “A Sleepin’ Bee,” with music from the estimable Harold Arlen, from their 1954 musical House of Flowers.

But was Capote spreading himself too thin? He took on almost any assignment that paid well, jumping from travel writing to celebrity interviews to whatever else beckoned. As a result, at age forty, Capote had only published three fairly short novels—impressive by most standards, but disappointing for a child prodigy of the pen, who had been writing for more than two decades and lauded as our next Hemingway.

I doubt anyone expected something as stunning as In Cold Blood from Truman Capote at this point. He was already drinking heavily and popping pills, and these problems were getting worse. “When I first knew him, we would have a little wine with lunch,” recalled Phyllis Cerf. “But during the writing of In Cold Blood his drinking grew, grew, grew, grew.”

Adding to the calamities, Capote had taken on an immense project. He wanted to create a fully immersive account of a 1959 murder in Holcomb, Kansas, blending news reporting and on-the-scene interviewing with all the techniques he had learned over many years of writing short stories and novels.

His goal was nothing short of inventing a new type of writing—he called it the non-fiction novel.

Faced with this challenge, Capote demonstrated an intensity of focus and self-discipline that he would never match again, following up every lead like a private investigator (often with the help of his childhood friend Harper Lee), and eventually compiling 8,000 pages of notes. In order to get all the details, he even befriended the murderers and, gradually losing his role as objective journalist, became part of the unfolding story.

Few were prepared for the sensation caused by the publication of In Cold Blood in four installments in The New Yorker. Although crime stories had been a mainstay of journalism for centuries, the Kansas murders had gotten little coverage in the national news. But Capote’s storytelling skills and descriptive powers turned them into a crime of the century, a classic story of the dark underbelly of life in America’s heartland.

The reader was captured from the very outset.

Just read the opening paragraph and marvel at an author who is always in control—yet somehow makes you feel as if the story is just telling itself, without any authorial intervention required.

The village of Holcomb stands on the high wheat plains of western Kansas, a lonesome area that other Kansans call ‘out there’. Some seventy miles east of the Colorado border, the countryside, with its hard blue skies and desert clear air, has an atmosphere that is rather more Far West than Middle West. The local accent is barbed with a prairie twang, ranch-hand nasalness, and the men, many of them, wear narrow frontier trousers, Stetsons, and high-heeled boots with pointed toes. The land is flat, and the views are awesomely extensive; horses, herds of cattle, a white cluster of grain elevators rising as gracefully as Greek temples are visible long before a traveller reaches them.

Such maturity and poise would be remarkable in any writer—but who could have guessed that partying, pill-popping, prurient Truman Capote could write with such total control, and keep it going for 350 hypnotic pages.

But in a way, this all makes sense. Capote had the benefit of his small town upbringing, which helped him understand Holcomb, Kansas. But he had also been an outsider as a child and in school, mocked and bullied, and this gave him an empathetic connection with criminals and convicts. Above all, he knew how to observe people and places—getting the former to speak their truths, and the latter to reveal their succinct suchness.

In both instances—with people and places—he grasped their virtues and their flaws. And, above all, he never judged. That helped him in dealing with both celebrities and criminals.

At one point in Conversations with Capote, Lawrence Grobel asks him:

Have you ever wondered why you are able to relate so well with murderers?

Because right away they realized I wasn’t passing any judgment on them. I had no opinion about them as a person regarding the fact that they’d killed or no matter what their crime had been, because I don’t

This seems like an aberration or character flaw—how can Capote not abhor these killers? But he works the same charm on the reader of In Cold Blood. That’s how Capote creates the impression of a story that reveals its own truths in its own way and at its own pace, with hardly any effort on his part as midwife.

Despite the appearance of ease, it must have taken tremendous efforts on his part to achieve this relaxed unfolding of such a dark, convoluted story. In Cold Blood somehow combined fiction and journalism, even while transcending both—delivering, page after page, what no newspaper or novel on their own could achieve.

The success was both immense and well deserved. The hardback version of In Cold Blood generated $2 million royalties within a few months. Paperback rights sold for a half million dollars. Movie rights also sold for a half million dollars—reportedly the highest payout for a book adaptation to date—and Capote also got promised one-third of the film’s profits.

By comparison, the average US salary in 1966 was just a bit over $4,000. But Capote’s earnings did not stop with In Cold Blood—he also demanded a large advance for his next book. This work, entitled Answered Prayers, promised to be another milestone in American fiction.

Just as he had invented the non-fiction novel with In Cold Blood, Capote promised to do something similar with Answered Prayers—which he touted as the great gossip novel. And if anybody could turn tawdry gossip into fine literature, it would be Truman Capote. After all, he knew every celebrity, and enough dirty laundry to fill up that 300-machine laundromat outside of Chicago.

The contract specified a delivery date of January 1, 1968 for Answered Prayers. Capote failed to meet the deadline, but somehow wheedled more money from Random House, and an extension to 1973. He missed that date too, and got another extension to 1974, and still another to 1977, and another to 1981.

Capote eventually extracted $1 million from Random House for a novel he never finished. And, as far as we can tell, never came close to finishing—although Capote told his publisher on at least two occasions that the manuscript had been completed.

Four extracts from Answered Prayers were published in Esquire in 1975 and 1976, and stirred up plenty of excitement—but in the worst possible way. Capote’s friends felt that that he had betrayed their confidences, constructing his gossip novel out of the barely disguised dark details of their private lives.

Truman Capote now found himself ostracized by the rich and famous. This wounded him deeply, and also cut him off from his supply of new gossip—which he needed for his work-in-progress. Perhaps he was genuinely surprised by this turn of events. After all, hadn’t he done the same charm-and-betray routine with those convicts in Kansas? But it’s one thing to violate the trust of a murderer on death row, and quite another thing to do the same with New York elites.

I doubt that Capote would have completed Answered Prayers even with all the support of his intended targets. But after the controversy generated by the Esquire extracts, he never regained his footing—not as a writer, not as a society figure, not even as a human being.

Truman Capote was now a wreck. Even his indefatigable biographer Gerald Clarke can’t keep count of the ailments.

“An exact account of his [hospital] stays is hard to come by; during the first few years of the eighties he was hospitalized in half a dozen states and Switzerland too.” In just one facility, Southampton Hospital, Capote got admitted “four times in 1981, seven times in 1982, and sixteen times in 1983.”

What was wrong with him? Pretty much everything.

Capote admitted that he had suffered a “semi-nervous-breakdown.” He got arrested for drunk driving. He went into rehab (unsuccessfully) and told friends that his depression was more dangerous than his drinking. He got hospitalized for phlebitis, and blood clots formed in his lungs. Grobel heard rumors that Capote was also hospitalized for epilepsy. He complained about stabbing chest pains. He had multiple falls, at least one resulting in a concussion.

Yet Truman Capote hadn’t even reached the age of sixty—and never would. He died on August 25, 1984 at age 59. The autopsy revealed no clear cause, just many contributing factors—including liver disease, phlebitis, and “multiple drug intoxication.” He had been taking several different barbiturates, codeine, Dilantin, and enough Valium to knock a person out.

Capote’s remains were cremated a few days later. As if in parody of the author’s outrageous and controversial life, his ashes were subsequently involved in various disputes and multiple robberies. Nobody can quite agree what happened to them.

Only one thing survived all this degradation—Capote’s reputation.

And that was something of a miracle. He had turned himself into a joke on late night TV. He had betrayed his closest friends. He had defrauded his publisher. Above all, he had betrayed his own talent—squandering almost the entirety of the last two decades of his life.

Despite all this, Capote’s personality was just too big, and continues to fascinate us one hundred years after his birth. I suspect there will be more movies and miniseries and documentaries—like Oscar Wilde, Capote didn’t need to write books to create a sensation. It just happened naturally whenever he walked into a room.

But we shouldn’t forget those books, even in our post-literate age. Truman Capote might be a terrible role model for how to life your life, but he is the best possible teacher of how to write a sentence, a paragraph, a page, an entire book.

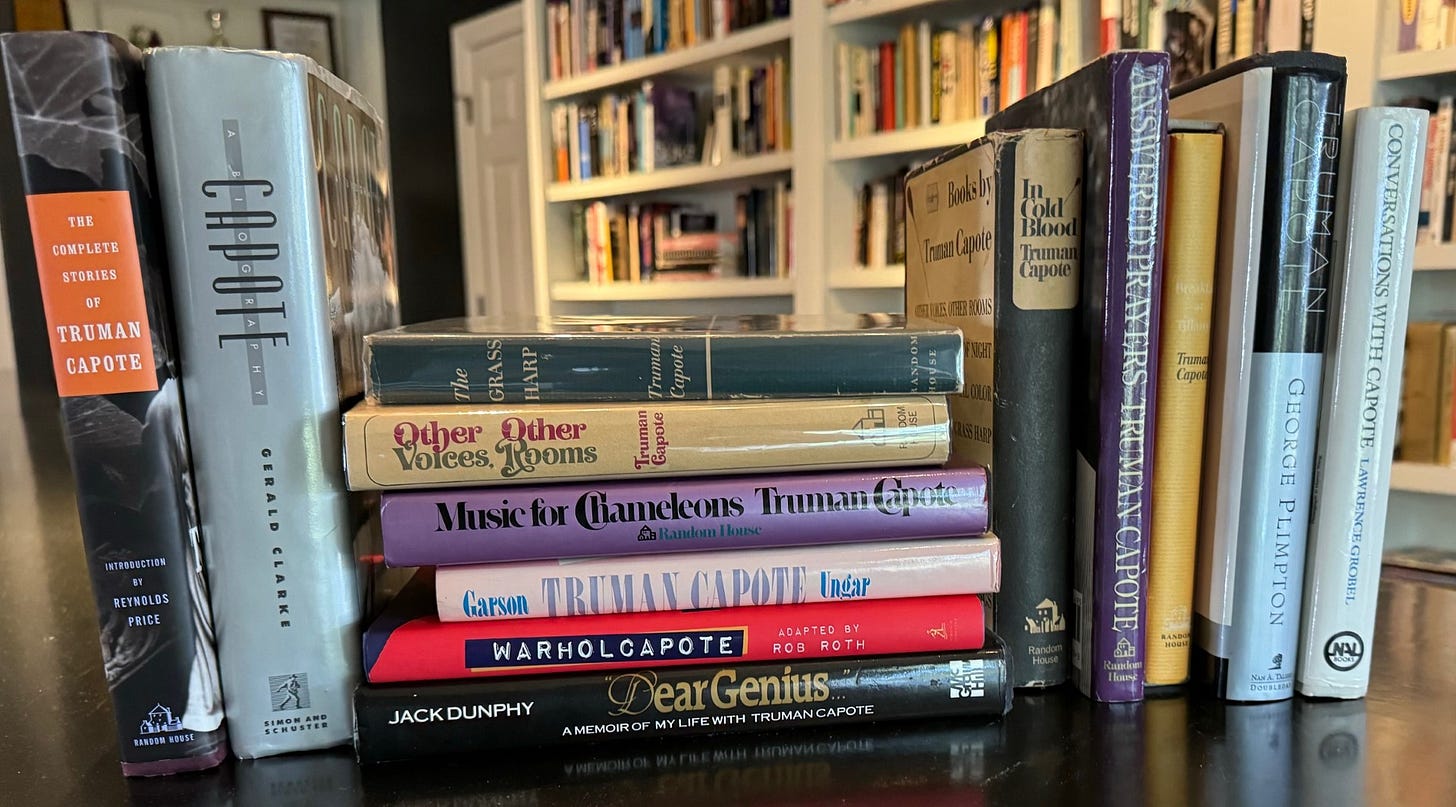

So I can say with total confidence, that the best part of Capote is still alive and available to all of us. It’s there on the shelf—the only safe refuge this prepossessing character ever found—and continues to invite our attention and demand our respect. Yes, despite all the wear and tear, the essential part of Truman Capote made it to 100 in very good shape. And I have every confidence that will still be true in another hundred years.

I watched Murder By Death last night, in honor of Maggie Smith, and there was Truman. "I hope he knows how to stop that thing!"

How about celebrating by listening to a different song that Truman co-wrote lyrics with Harold Arlen, "Don't Like Goodbyes" sung by Frank Sinatra, arranged by Nelson Riddle, and played by The Hollywood String Quartet? I think this collaboration alone will be good for another ~250 years of cultural significance!

https://youtu.be/8my-sSiFaHE?feature=shared