Harrison Ford and the Origin of Western Civilization

We cover lots of ground at The Honest Broker

The best conversations take you on wild journeys. I’m sharing one of those today.

Below I talk about my favorite adventure films. But then we go on a long trip—you can call it an odyssey, if you like—before coming home with some big conclusions.

Along the way, we deal with everything from Raging Bull to the Book of Revelation.

So put on your seatbelts. . .

If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a premium subscription (for just $6 per month).

TED:

So what do want to talk about today?

INTERVIEWER:

Today I want you to stop acting so elitist—that’s why we’re going to talk about action films. What’s your favorite?

TED:

I’m not as elitist as you think. I’ve written hundreds of essays about science fiction, horror stories, locked-room mysteries, TV westerns, and other types of popular entertainment.

By the way, I love action movies of all sorts—I even have a Jackie Chan poster on my bedroom wall.

INTERVIEWER:

Is that true?

TED:

No, I just made that up.

But I do enjoy Jackie Chan’s movies, especially the early ones. I would consider putting a Jackie Chan poster on the wall, but Tara would veto that.

She already made me take down my autographed photo of Jake LaMotta—she said it clashed with the decor.

INTERVIEWER:

She is probably right. But let’s go back to my original question. What’s your favorite action film?

TED:

That’s hard to answer. There was a very good movie about LaMotta…

INTERVIEWER:

That doesn’t count. It wasn’t a real action movie. Pick another one.

TED:

Huh? There were plenty of fight scenes in it. But I’ll take you at your word, and choose another movie

[Ted stops and thinks.]

Okay, I’ve got an answer for you. The action movie I’ve seen most often is The Fugitive—starring Harrison Ford and Tommy Lee Jones. I’ve watched it so many times, I’ve lost count.

INTERVIEWER:

What do you like about it.

TED:

For a start, it’s the exact counterpart of Homer’s Odyssey….

INTERVIEWER:

Gimme a break, you’re doing it again. I said no elitist stuff today. So you’re not allowed to talk about Homer and ancient epic poetry.

TED:

Hey, hear me out. Homer’s Odyssey is also an adventure story—and not for elites. This story has entertained youngsters for thousands of years.

And it’s my favorite kind of adventure story.

INTERVIEWER:

Why is that?

TED:

The Odyssey was the first adventure story in Western culture about a hero who prevails through intelligence and reasoning, not fighting and bloodshed.

That’s a big deal. It signals the moment when the West emerged from savagery—assuming that we have emerged from savagery.

Odysseus is not a brave solider—if you’ve read Pseudo-Apollodorus, you will know that he tried to avoid fighting in the Trojan War by pretending to be crazy.

INTERVIEWER:

Sudoku app adores us? What the devil are you talking about?

TED:

Don’t worry about Sudoku. I’m trying to explain that Odysseus was the first adventurer who hates adventure. There’s a postmodern concept for you. He doesn’t even like fighting—he prefers to use his wiles and cunning.

This is the greatest turning point in Western culture. We finally have an alternative to the reciprocal violence that dominates so much of human history. The worst mistakes we’ve made in the West have taken place when we have forgotten that alternative.

But, of course, it’s also a breakthrough in storytelling.

Homer’s previous epic, the Iliad, is all about bravery and violence on the battlefield. Some 240 battlefield deaths are described during the course of that brutal poem—frequently related in grisly detail.

But the Odyssey is totally different. The hero is actually portrayed as a coward.

Homer drops a hint when he says the Odysseus places his ship in the exact middle of all the Greeks boats on the shore of Troy—that’s the safest place in the event of a surprise attack by the Trojans. Homer doesn’t say it explicitly, but he implies that Odysseus always had an escape plan, and needed to ensure that his ship was available for a hasty retreat.

INTERVIEWER:

What does this have to do with Harrison Ford and The Fugitive.

TED:

It has everything to with it. In The Fugitive, Harrison Ford succeeds through cunning and intelligence. There’s that great scene when Ford’s colleague tells Tommy Lee Jones: “You will never find him. He is too smart.”

Just as the Odyssey represents a shift away from the obsessive violence of the Iliad, Harrison turns his back on the constant battling of his previous manifestations in Star Wars and Indiana Jones.

In the movie poster for The Fugitive, Ford is actually running away from the fight—much like Odysseus tried to do.

So this is a great moment in Hollywood action movies. There’s actually very little fighting in The Fugitive. Ford even risks capture at one point by saving a person’s life. And that makes perfect sense because he is playing Dr. Richard Kimble, who—like all doctors—has taken a Hippocratic oath to avoid harm and do good.

That’s why The Fugitive is so satisfying to watch. We finally have a hero who really does good deeds and avoids reciprocal violence. And when he must engage in conflict, he out-thinks his opponent—instead of fighting and killing.

In fact, the entire point of the film is that Dr. Kimble is an innocent man. He has been falsely accused (of murdering his wife), and his only goal in this movie is to prove his innocence and his commitment to doing good.

I won’t give away spoilers. But in the final minutes of the film, he applies that Hippocratic Oath to do good through medicine and healing in a very unexpected way. You might even say that he saves thousands of people—in addition to himself.

But there are many other similarities between The Fugitive and Homer’s great epic the Odyssey.

INTERVIEWER:

What other similarities?

TED:

Like all great epic poets, Homer starts the Odyssey in the middle of the story—literary critics call this in medias res. Homer may even have invented this storytelling technique.

The Fugitive follows the same pattern. The movie begins after our hero Dr. Richard Kimble has been falsely accused and convicted of his wife’s murder. So (as in the Odyssey) we must learn about these incidents through flashbacks.

In the case of the Odyssey, our hero must battle a one-eyed monster—the Cyclops!—in order to survive and prevail. The same thing happens in The Fugitive, except that Dr. Kimble needs to deal with a one-armed monster who murdered his wife.

INTERVIEWER:

This is just coincidence. Stop playing games with me…

TED:

You’re totally wrong about that.

Let me ask you a question now. What’s the name of the one-armed man in The Fugitive?

INTERVIEWER:

I have no idea.

TED:

The character’s name is Sykes. This reference to the Cyclops would be obvious to any classicist in the audience.

Can’t you see that the filmmaker wants to remind us of the Odyssey?

INTERVIEWER:

You’re blowing my mind. Is that for real?

TED:

Go ahead, check it out for yourself.

But let me go on. There’s a whole web of connections here.

I’m not even going to talk about the obvious ones—for example, Homer frequently refers to Odysseus as “great-hearted” while Dr. Kimble is an actual heart surgeon. And Odysseus’s troubles began with Helen of Troy, while Dr. Kimble’s problems begin with his wife Helen—both victims of fighting men who intrude into their peaceful lives.

Those are just tiny details. The plot is the main source of my interest here.

In the Odyssey, our hero must survive a ship wreck—and later must escape from captivity on an island, where Calypso wants to hold him for the rest of his life. In The Fugitive, Harrison Ford needs to survive a train wreck—which allows him to escape from captivity as a prisoner on death row, where he would otherwise spend the rest of his life.

In the Odyssey, our hero eventually returns unexpectedly to his native land—the island of Ithaca—where he faces his final and greatest challenges. In The Fugitive, the US Marshalls are shocked when Dr. Kimble returns to—can you guess it?—his home town of Chicago.

That’s the last thing they expected from a runaway fugitive. “Sonofabitch,” declares Tommy Lee Jones, “our boy came home.”

But, of course, a homecoming is necessary in this type of adventure story. These heroes must return home to resolve all the dangers and obstacles they face. And in that familiar terrain, both heroes prevail against heavy odds.

By the way, both the Odyssey and The Fugitive culminate with an unexpected confrontation in a crowded banquet hall in that same home town. The parallelism is now completed.

And this brings me to my favorite part of the story.

INTERVIEWER:

What is that?

TED:

My favorite aspect of the Odyssey is that Homer created an adventure story where the hero just wants to get home.

As I mentioned before, he hates adventure. He’s really just a husband and father. His highest goal is to restore domestic tranquility at the homestead. That’s the only reason why he fights—not for honor or glory or wealth or all the other trappings of victory.

I love that. I can relate to it.

If I were forced into an adventure of this sort, that would be my same goal. I’d just want to get home as soon as possible.

Can’t you dig it?

Yes, I’d be willing to fight for my home and family. But I’d prefer to imitate Odysseus (or Dr. Richard Kimble) and use ingenuity and cleverness instead of violence. That’s a much more satisfying kind of adventure story.

In fact, that should be our ideal adventure story—purged of vengeance and reciprocal violence.

By the way, it’s worth remembering that both Harrison Ford and Andrew Davis, the director of The Fugitive, grew up in Chicago. So they were both very aware of this homecoming angle to their story.

I don’t think critics understand the full significance of this.

INTERVIEWER:

What do you mean?

TED:

The rise of Western culture begins with the shift from hunting economies to farming and pastoral economies—or what we might call homesteading. Farming and ranching are the foundation for stable communities with deep roots in a settled land. This later leads to the rise of cities and universities and running water and all the other things we call “civilization.”

Hunters are always on the move, so they are less interested in creating these deep roots in an unchanging geography. In many instances, they operate as nomads.

Homer’s Odyssey marks the decisive shift to a culture built on settling down—with permanent home and farm animals and all the rest.

So it makes sense that Odysseus wants to get home. That’s the trademark of this way of living. This is now the bedrock motivation on which society will be built.

That’s an exceptionally mature view of the good life. Many people still haven’t figured it out. But Homer understood all this thousands of years ago.

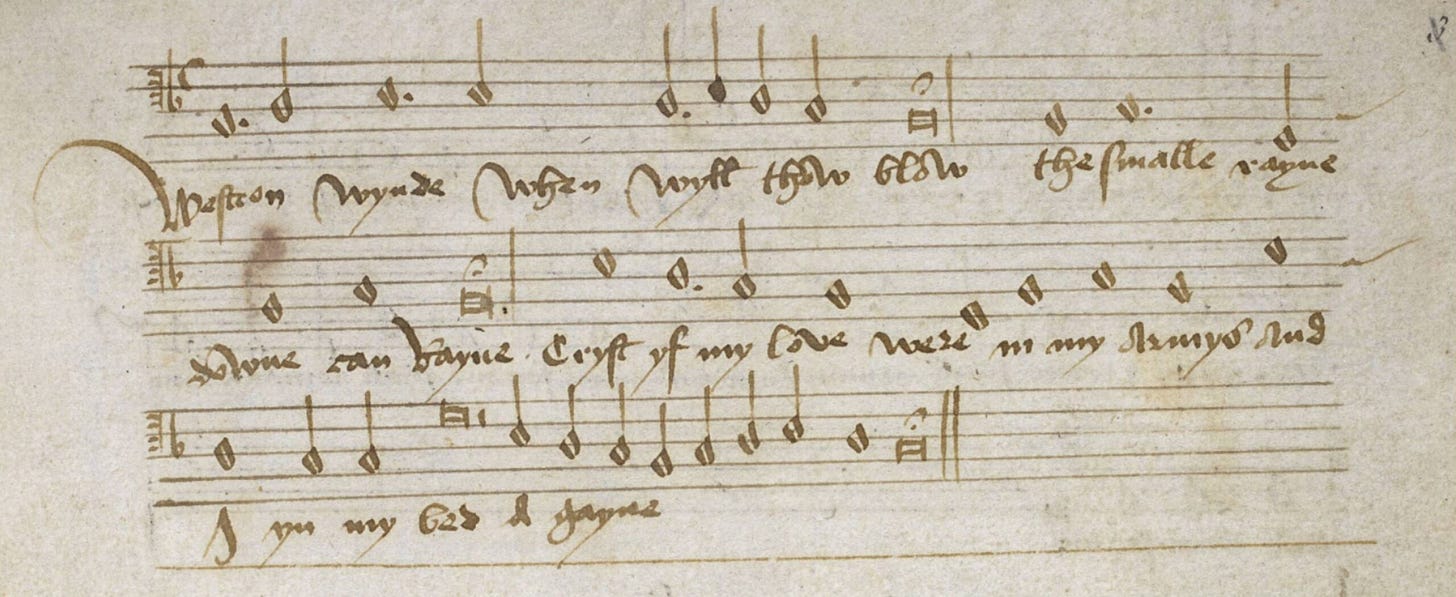

You see this nostalgia for home elsewhere in thriving cultures. It’s pervasive in the Jewish tradition, of course. And you will find it at the start of settled English culture—for example in the “Westron Wynde” song—whose singer just wants to be back home in bed with his true love:

Westron wynde when wyll thow blow

The smalle rayne downe can Rayne

Cryst yf my love were in my Armys

And I yn my bed Agayne.

You may think that the great achievements of the West are built on armies and killing. I prefer to view it as the result of more peaceful longings to be back home and in bed again.

This is in fact the greatest literary theme of Western culture.

INTERVIEWER:

That’s not true. I can’t think of a single great novel about wanting to return home.

TED:

You’re looking in the wrong place. The novel is decadent literature.

But if you look at the epic and extended works of poetry, the dominant theme is the loss and recapture of home. That’s why these works often come in multiple parts—such as the Iliad and Odyssey, or the three parts of Dante’s Divine Comedy, or Milton’s Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained.

At the beginning, you lose the home. At the end you regain it—perhaps on a higher level. By the way, this is why the Bible is broken up into an Old Testament and a New Testament. You lose a homeland in Genesis and get a new one in Revelation—I’ll let you figure out the respective value of those two pieces of real estate.

I could tell you a similar story about the great Roman epic, the Aeneid—or the poems of the Grail myth, or Wordsworth’s The Prelude, and so many other works of this sort.

Novelists forgot about the homecoming story—the greatest tale of them all. Well, except for maybe Joyce and Proust and a few others. (By the way, Joyce’s Finnegans Wake not only ends up at the beginning, but we actually return to the Garden of Eden—talk about a homecoming!)

But those kind of novels are rare. And this neglect of the homecoming theme is what imbues the novel with a constant undercurrent of angst.

Even comic novels are sad when you probe deeply into them. Lucky Jim really isn’t so lucky. Your Great Expectations are never really all that great.

The typical theme of the novel is that you can never go home again. Those who try inevitably fail—like the Great Gatsby.

Filmmakers have also forgotten the homecoming story. That’s unfortunate.

And that’s why I like The Fugitive. It’s a homecoming tale disguised as an adventure—hence it redefines adventure. It’s an action film that redefines action. Along the way, it provides a playbook for rising out of bloodlust and Girardian reciprocal violence.

We need more movies like that. Maybe we even need a society more aligned to that.

INTERVIEWER:

Maybe you’re right. So I will cut you some slack this time.

But this is still too highbrow and elitist for my tastes. Next time I want to talk about something more down to earth, like TV wrestling….

TED:

Ah, that has an impressive ancient history too. In Pindar’s odes from the 5th century BC you will find a curious obsession with wrestlers….

[The voices fade out, and the scene fades to black.]

The final words of the Lord of the Rings- the final volume of which is The Return of the King - is Sam saying "well I'm back," turning the whole darn thing into a homecoming tale.

I would also point out that dozens and dozens of classic bluegrass songs have the longing for home as their central theme.

A signed photo of Jake LaMotta should *not* be languishing in a box! Surely there must be a wall in your home that can accommodate that!!! (My Dad boxed Lew Tendler in a gym in Philly somewhere when he was young. Tendler won, of course. My Dad taught me a left hook when I was 10. He really wanted a son.)