12 Things I Learned from René Girard

How a thinker who hated trends & fashions became trendy & fashionable

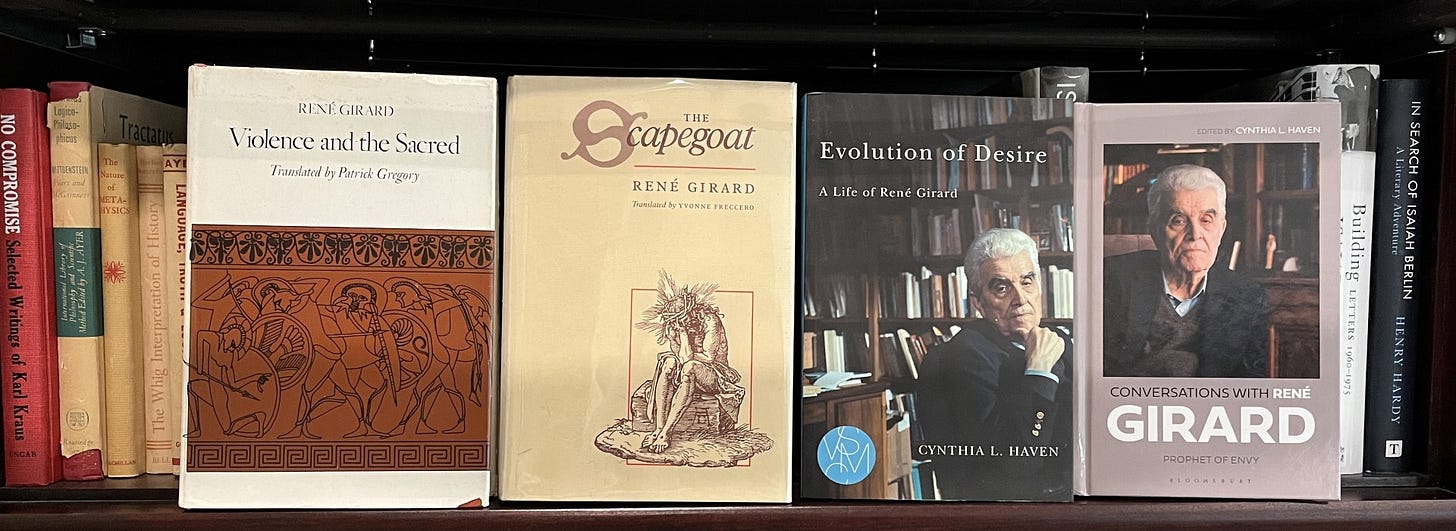

Some readers have noticed that I frequently praise René Girard (1923-2015), a critic and social theorist who has become eerily relevant in recent years—gaining tremendous influence since his death a decade ago.

But his trendiness is a little alarming.

Girard devoted his life to exposing the lies behind fashions and trends. And now, after his death, he is fashionable and trendy. It’s almost like some kind of punishment.

I doubt Girard wanted to influence venture capitalists and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. Or social media pundits. Or even music critics like me.

But it’s happening.

And for a good reason. That’s because his theories, drawn from literature—of all places!—seem to explain so much of what’s taking place right now in society.

When Girard writes about ancient Greek tragedy, he seems to be describing Instagram and social media. When he analyzes Flaubert or the Book of Genesis, he somehow explicates the current political situation. By looking at what’s old, he clarifies what’s new.

I’m not the only person to notice this. But like many of his current readers, I was late to the party.

Back in the day, I sometimes ran into Girard on the Stanford campus and around Palo Alto. But I was a skeptic back then—especially because of his peculiar reliance on literature to explain sociology. Hence, I never took advantage of the opportunity to speak with him, much to my regret now.

But, like others, I didn’t grasp the depth of his concepts until I started applying them in my own work. Nowadays I frequently rely on his ideas in analyzing situations and predicting future developments.

I know this sounds strange, but even my ethical values have shifted because of reading René’s work. If you take him to heart, you’re almost required to treat people with more tolerance and compassion.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

That short intro gives you some idea of how Girard has impacted both my vocation and personal life. That’s why I want to share a quick guide to the insights I’ve drawn from his writings.

Some of the concepts below are taken directly from Girard, while others reflect my adaptations of his ideas. I need to do this because Girard rarely wrote about music (just a bit about opera), and never discussed popular culture, but I’ve found his concepts very useful in my work in both areas. (See, for example, my essay “Why Do They Burn a Man at Burning Man?”)

Now let me jump right in with a list of a dozen things I learned from René Girard.

12 THINGS I LEARNED FROM RENÉ GIRARD

By Ted Gioia

1. It’s embarrassing to admit, but most of what we do is based on imitating others.

Imitation is such a childish motivation. We see toddlers doing it, or even animals at the zoo. People resist viewing themselves as imitators. They want to believe they’re more sophisticated than that—clinging to deeper explanations of their desires and behaviors.

It’s so much cooler to talk about our Freudian unconscious or Marxist class ideology or some other highfalutin theory. Girard cuts through this rhetoric. He exposes imitation (or “mimetic desire,” in his words) as pervasive in our lives—in our rituals, our institutions, our shopping and socializing, and (above) all in our violent passions.

2. Imitation is the economic engine of most businesses—just look at the big social media companies or fashion brands—but it’s always disguised.

Because imitation is shameful (see above), the institutions serving it cannot openly admit its power. They will never say that you’re just imitating your friends and neighbors, so they talk instead about fashion, trends, keeping up-to-date, etc. You will never see a single ad that openly proclaims: “Buy these running shoes because other people are doing it”—but that’s really the implicit message.

In the corporate world it’s called benchmarking or viral marketing or gets hidden behind some other jargon. There are a hundred ways to hide mimetic desire, and these methods of deception are more powerful than we realize—because so much is at stake.

That’s because the easiest way to control people is by manipulating their impulse to imitate.

3. We need to expose the deadly disguises of imitation, because it causes so much harm.

By desiring the same thing as our neighbor, we are drawn into inevitable conflict. Mimetic desire turns into mimetic rivalry—in everything from love to war. That’s the reason for the injunction against “coveting your neighbor’s wife.”

Girard claims this is emblematic of how mimetic impulses destroy a community. You try to seize what your neighbor desires most. But this happens on a much larger scale in sociopolitical and economic conflicts. The truthteller has a special responsibility to expose imitative passion—because it is the force behind so much violence, persecution, and scapegoating.

4. Imitation leads to blood feuds and reciprocal violence—escalating like Mafia wars—which are traditionally resolved by the sacrifice of a scapegoat.

In ancient times, an actual bloody sacrifice took place. In other situations, a ritualized sacrifice is served up. Today, it might be somebody blacklisted in Hollywood or canceled on social media. (Heroes often turn into scapegoats—see item #5 below).

To halt (temporarily) the blood feud, violent impulses of the combatants are targeted at the scapegoat, instead of at each other. (Here’s an example: After 9/11, Democrats and Republicans came to together and focused their hostility on non-existent weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, creating a short-lived lull in their political feuding.)

“Nine-tenths of politics,” Girard asserts, is “choosing the same scapegoat as everyone else.”

5. The scapegoat combines opposites—and is often both victim and hero, profane and sacred, guilty and innocent, dying and resurrecting.

Girard gives examples of sacrificial victims who are treated with awe and reverence, receiving special favors—and then they get executed. (I believe this helps us understand rock stars and other celebrities, who channel the same opposed impulses—think of the Rolling Stones at Altamont or the Sex Pistols at Winterland). The most intense emotions, both positive and negative, are targeted at these paradoxical figures. In many cultures, the victim who is offered in sacrifice even gets turn into a god—and thus originates a powerful ritual or myth.

6. The persecution of scapegoats is a central force behind organizations and belief systems—but this can never be mentioned.

Witch hunters for example, cannot admit that the witches are innocent victims, because that would destroy their own power base and purpose. Girard offers many other examples, drawn from history, mythology, literature, and religious texts. He shows that the scapegoat mechanism is the most powerful secret in the world—because it is both necessary to group formation, yet no hint of it can be acknowledged within the group.

7. Humans fail to perceive own scapegoats—so persecution continues while everybody absolves themselves from guilt.

Even Girard himself is forced to admit that, despite his expertise on the subject, he is prevented from seeing his own complicity. “I am not aware of my own [scapegoating],” he confesses, “and I am persuaded that the same holds true for my readers. We only have legitimate enemies. And yet the entire universe swarms with scapegoats.” The persecutor is always someone else.

The “enormity of this mystery” indicates that scapegoating is deeply embedded in the human psyche. Our mimetic rivalry drives us to punish, and we resist even the slightest hint that our victim might be an innocent scapegoat.

8. Our most violent impulses are stirred up by similarity, not difference.

Because our desires originate in imitation, we get into the bitterest conflicts with the people we mimic—we want what they have, and vice versa. Even when we battle the other, it is usually because the differences between us are eroding.

For example, hatred of immigrants (and their hatred of the locals) is amplified when both live in the same neighborhood and the barriers that previously existed have been removed. There are hundreds of other examples, but they all derive from the other refusing to remain the other, and instead showing up on our street, in our country club, at our doorstep, or somewhere else where they start to resemble us.

Girard believes that erosion of differences are the source of violence, even more than difference itself. And nothing is more dangerous than total sameness. Consider how many myths involve battles between twins or siblings, or the ominous role of the ‘double’ in literature.

If you met somebody who is your exact duplicate, you probably would decide to kill this double.

9. Enemies resemble each other, because of mimetic rivalry, but this is another secret that cannot be mentioned.

The most obvious examples come from sports rivalries—Bird versus Magic, Ali versus Frazier, etc. The combatants seek the exact same prize, and follow almost identical training and lifestyle regimens in their pursuit of it. Maybe years later, after both have retired from sports, this similarity can be recognized, but in the heat of the battle the opponent must be a hated enemy, standing for everything we abhor.

This isn’t just a sporting phenomenon. It happens everywhere. In most spheres of life, opposed forces are never allowed to see how much they resemble those they hate the most.

As a result, the concept of the nemesis has more explanatory value than any worldview based on scapegoating enemies.

10. Artistic idioms often originate in imitation and ritualized sacrifice.

Girard rarely mentions entertainment—which is unfortunate, because his concepts are rich in implications for performers and critics. But consider the obvious example of dancing, where the pleasure (for both performer and audience) is intensified by the ritualized imitation of movement. I detect similar meanings everywhere in arts and entertainment—from jazz cutting sessions to youngsters imitating the hair styles of their favorite music stars.

11. Our culture rightly celebrates the help and defense of victims, but we need to be vigilant against a ‘super-victimology’ in which this merely leads to targeting and punishing new scapegoats.

The urge to reciprocal violence is so powerful that we often feel that only two roles are available to us—victim or oppressor. We need to neutralize both of those ways of being in the world.

Nobody should be a victim. Nobody should be an oppressor.

12. We can escape the endless cycles of reciprocal violence—but only by rising above our impulse to vengeance and working instead to delegitimize the drive to punish and scapegoat.

“I believe that the knowledge of violence can teach you to reject violence,” Rene Girard insists. But this knowledge is submerged in the rhetoric of vengeance, which is pervasive, and is the most destructive force in human society. Only by rejecting its propaganda, do we have a real chance to find harmonious ways of living together.

Our instinct is to respond to violence with violence, but our higher path is to destroy the legitimacy of all scapegoating and violent reprisals. This is all the more important in the modern world, Girard warns, because our scapegoating rituals are losing their efficacy—it’s easy to see through their lies. Hence they no longer unify the public in a cathartic resolution. Meanwhile destructive technologies get more powerful and easy to access with each passing year.

This is a deadly situation, and means that we now must consciously choose the path of love and forgiveness. In a world in which sacrificial rituals have lost their power to pacify, this is our only safe path forward.

Here’s a graphic summary of the above.

Great article. But I feel it does no good to 'secularize' Girard and gloss over the roots of his theory - which is Christian. The Devil is the root of mimetic desire, and it was Christ's sacrifice that demonstrated how it is overcome. It's because the scapegoat mechanism is so pervasive that the Christian story was so compelling throughout history.

I love this line: "Girard devoted his life to exposing the lies behind fashions and trends. And now, after his death, he is fashionable and trendy. It’s almost like some kind of punishment."

Our legacies are so often ironic. Reminds me of Carl Jung who reportedly said: The best thing about being Carl Jung is that I'll never get to call myself a "Jungian".