Why Do They Burn a Man at Burning Man?

Or dark truths René Girard should have told us about pop culture, but never got around to saying

How do you celebrate Labor Day weekend? At the annual gathering known as Burning Man, enthusiastic participants set fire to a large wooden effigy—which they call The Man. This is truly sticking it to the man, in the parlance of the counterculture. And the stick here is a log, soaked in fuel and bacon grease, then set ablaze with a large magnifying glass.

The bacon grease was added as a “sort of joke, but it really does work,” comments one participant. But before the effigy is set alight, a ritualistic fire dance takes place, and finally The Man is ignited—only to rise again at next year’s event.

Large gatherings are risky nowadays, but Burning Man has gone online. In 2021, you’re invited to participate in the “virtual burn” from the safety and seclusion of your home.

Could anything stop this annual event? Probably not. The organizers proudly proclaim on their website: “The Man will always burn!”

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported newsletter. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. The best way to support my work is by taking out a paid subscription.

The whole Burning Man gathering is viewed by many as a “sort of joke”—dismissed as New Age affectation or a strange variant of hipster posturing. Yet the size of the crowd—almost 80,000 people head into a godforsaken Nevada desert in summer—is no laughing matter. And the organizers spare no effort in conveying the philosophical underpinnings of their grand annual conflagration–even publishing their “10 Principles of Burning Man”—including “decommodification,” “gifting,” “inclusion,” etc. They also share an online bibliography of fifty books related to Burning Man.

I laughed at Burning Man too—at least until I started doing research into the deep connections between pop culture and ritual sacrifice. This isn’t a subject that shows up in music history books, and for a very good reason. The connections between live performances and violence are undeniable, but also disturbing to consider. And the most ominous rituals of them all are those involving arbitrary violence directed at an innocent victim. In these macabre contexts, murder is incorporated into the event for reasons that seem arbitrary or villainous or just plain weird.

Yet the arbitrary nature of the sacrificial victim is essential to the success of the ritual. That is one of the key learnings we draw from René Girard (1923-2015), a pathbreaking thinker who life’s work focused on the importance of ritualized sacrifice in human culture. I believe that Girard’s 1972 book Violence and the Sacred is one of the most significant scholarly works published during my lifetime—full of rich implications for anyone who cares about the origins of our commercial and cultural institutions, or even about contemporary phenomenon, such as social media and generational conflict.

Consider how many children’s game songs involve arbitrary victims—“London Bridge is Falling Down” or “Ring Around the Rosie” or that game of symbolic violence so deeply associated with music that we merely call it ‘musical chairs.”

I almost never encounter even passing mention of Girard’s work in music scholarship. That’s unfortunate, but Girard himself is somewhat to blame. He didn’t have much interest in commercial music or pop culture. Frankly, I can’t recall a single passage in his books where he pays close attention to a hit song. And he certainly didn’t pay much attention to large-scale counterculture happenings such as Burning Man. Yet at the very moment he was researching and writing Violence and the Sacred, rock concerts and other large gatherings of the younger generation were showing more and more resemblance to the sacrificial rituals Girard analyzed in his most famous book.

Girard was more focused on literature. He devotes a huge portion of Violence and the Sacred to detailed analysis of the sacrificial ritual as setting the foundation for ancient Greek tragedy. But music historians ought to pay attention here too. The very word ‘tragedy’ combines tragos (goat) and aeidein (to sing). This is not happenstance, but simply evidence that the ancient Greek dramatic spectacle began, according to my view, as a musical ritual involving the sacrifice of a goat (and perhaps, at an earlier stage, a human victim).

Ancient music history is filled with these sacrificial rituals, although they are rarely studied or even discussed. You could even make a case that music was essential to these rituals because the sound of the instruments was sufficiently loud to drown out the unsettling cries of the victims. Not only did early Jewish scriptures explicitly condemn this practice—associated with the ancient Canaanites—but the Hebrew word for drum, toph, is actually linked to the Tophet, the location in Jerusalem where the sacrifices took place. These practices would not have been criticized in sacred texts if they hadn’t been frequent and familiar.

We don’t know much about these rites, but allegedly they involved “passing a child through fire”—a clear antecedent of Burning Man. The word tophet is also applied by archeologists to cemeteries of children, who seem to have served as preferred victims in the human sacrifice. This is gruesome, and I will leave the subject behind as quickly as possible. But consider the fact that the toph drum probably derives its very name from ritualistic murder.

Plutarch tells us that the same thing happened in ancient Carthage, where music was played during the ritual, not to sanctify it, but to drown out the cries of the victims. “The whole area before the statue,” he described, “was filled with a loud noise of flutes and drums so that the cries of wailing should not reach the ears of the people.”

A similarly ominous linguistic double signification is found in other settings. In Ewe tradition, for example, the word adabatram refers both to a dance performed by executioners and “the most important of all the war drums in Northern Ewe,” according to scholar Misonu Amu—who adds that the ‘drum is always decorated with skulls of war captives. . . . In the past only human sacrifice was made to the god before the drum was played.” Today you will encounter this ritual described as a funeral dance—not incorrect, given its origins. But that hardly encompasses the full lineage of adabatram music.

In fact, drums are linked to sacrificial ritual in every region of the world. In some places (Africa, South India, etc.), the sacrifice is made to the drum—which is believed to embody a deity or powerful spirit. In other instances, for example among the Incas, the skin of the sacrificial victim is turned into the drum. But whatever the particulars, the drum is viewed with awe, perhaps even fear, in the context of these ritualistic connections.

If you think we have long outgrown such primitive practices, consider how many children’s game songs involve arbitrary victims—“London Bridge is Falling Down” or “Ring Around the Rosie” or that game of symbolic violence so deeply associated with music that we merely call it “musical chairs.” Strange as it sounds, the screaming patrons at Burning Man all learned about musical sacrifices as part of their earliest playground experiences.

But no sphere of modern pop culture reflects this inherent tendency to violence more than rock—and especially during the period when René Girard was formulating his theory of violent ritual. This is why I’m so surprised he didn’t pay attention to it.

The most prominent example is, of course, the notorious Altamont concert on December 6, 1969—remembered today for the stabbing death of Meredith Hunter in front of the stage during a performance by the Rolling Stones. But just a few weeks earlier, the murderous Charles Manson gang relied on the Beatles’s song “Helter Skelter” as an anthem in their own quasi-ritualistic killing spree. How strange that the decade would come to a close with the music of the two defining bands of the era—so focused on peace and love, according to the leaders of the counterculture—having their songs co-opted in senseless murder.

Yet if we only focused on such moments of actual bloodshed, we would miss the real importance of rock music as a symbolic enactment of ritualistic violence. The goal of such rituals is create an audience frenzy that stops just short of actual murder—usually avoided by transferring the violent impulses on to a surrogate.

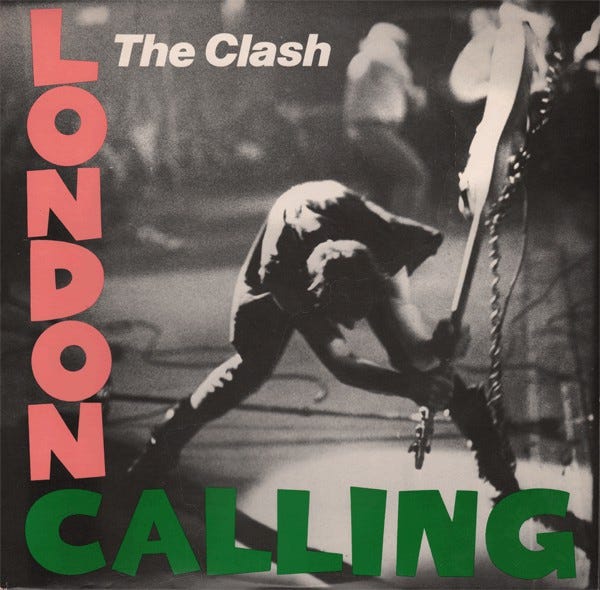

In many instances, the musical instrument serves as that surrogate, a symbolic replacement for the sacrificial victim. Just consider how many rock stars have gained notoriety by destroying their instruments on stage. Jimi Hendrix’s decision to set fire to his guitar at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival has proven so gripping that it later showed up twice on the cover of Rolling Stone, and has even been commemorated in a bobblehead and toy action figure. And it’s all too revealing that when a music magazine ranked the best rock photos of all time, the Hendrix photo only got second place—losing out to the cover photo from the Clash’s London Calling, which shows Paul Simonon destroying his Fender bass during a New York concert.

Is it mere coincidence that the two most celebrated images in the genre’s history involve the destruction of a musical instrument? But just consider all the other examples from rock history—the legend of Jerry Lee Lewis setting his piano on fire (perhaps apocryphal but now a world famous incident), Jeff Beck destroying his guitar (and causing a riot) in the film Blow Up, Keith Moon of the Who wrecking his drum kit with explosives on US television, etc. etc.

Then consider the strange phenomenon of rock stars trashing their hotel rooms. What other profession takes pride in being such a lousy guest? But rock ‘n’ rollers were expected to do this. I could fill up the whole article with accounts. But here are a few videos, for example Keith Richards throwing TVs off balconies.

Or Keith Moon destroying a hotel room for a TV special.

And sometimes rock stars did even worse damage in a hotel room. Consider Sid Vicious’s alleged murder of Nancy Spungen at the Chelsea Hotel in 1978. But the victims were often the musicians themselves (Janis Joplin, Whitney Houston, Jimi Hendrix, etc.) who checked in, but never checked out. The details are disturbing, but equally unsettling is the larger question: Why are rock fans so focused on commemorating, indeed sometimes even celebrating, these senseless, violent acts?

If we can believe Girard, the violence may be somewhat arbitrary, but not necessarily senseless. The sacrificial victim becomes the focal point of pent-up energies and frustrations that might find even more destructive targets if not for this ritualized catharsis. Girard suggests that the sacrificial victim is all the more necessary in times and places where individuals find themselves immersed in social chaos and reciprocal attacks of various sorts. So it makes perfect sense that Girard would write his book—and that rock stars would start destroying instruments—during the same period that brought about the Paris riots, Vietnam protests, and the most prominent political assassinations of the century. If you were looking for a period to study the sacrificial ritual, the late 1960s would be at the top of your list.

Even though Girard was not a music historian, he still provides us with the right conceptual framework for understanding the role songs play in these performances and rituals. The victim in the sacrifice, he explains, is an unusual kind of scapegoat—often treated with extraordinary reverence and adulation before the moment of violence. Again, he makes no reference to rock stars in his work, but this is an invaluable perspective to bring to bear on the way society treats music stars who die young—they are both heroes and victims, celebrated and blamed, role models and cautionary tales. By grasping the larger history of the scapegoat, we understand how much our perspective is distorted by the uses to which the dead rock star’s life is applied. So we shouldn’t be surprised that Jimi Hendrix or Amy Winehouse or Robert Johnson lost their status as individuals and get turned into myths. To some extent, that’s the role our culture wants these musicians to play posthumously—so much so, that an attempt to find the “real” Robert Johnson, for example, misses much of the point of why we care about these artists in the first point.

This is a gloomy topic, but there is a positive side to it. Girard again helps us grasp it. The violence targeted at the victim helps to heal ruptures elsewhere in society. By uniting in their focus on the scapegoat, the warring factions come together and forget their animosities, at least for a short while. If the sacrificial ritual can be purged of its actual physical violence—turned into a symbolic event—while still retaining its soothing and calming aspects, this ought to be viewed as a positive contribution to the greater good.

I believe that musical performance plays that role in many situations. It enacts a violent conflict—which might be as vague as a battle between the soloist and the orchestra in a concerto, or as specific as Jimi Hendrix setting his guitar on fire. But the impact on the audience is to purge violent impulses.

What better way to do that than by setting a huge effigy of “The Man” on fire? So I don’t laugh at Burning Man. Maybe it has become a gathering for hipsters, posers, wannabes and hangers-on. But I suspect some true visionaries make their appearance as well. I’m not sure I can always tell them apart. Then again, I’m not sure it really matters. The mere act of setting fire to the symbolic victim can be inherently beneficial, no matter which constituency is holding the match.

Intensely interesting.

Most would argue there should be some degree of *philosophical* violence present at a rock venue — against the status quo, the political climate, the authorities, the ex lovers ...

It's something to consider when we collect ourselves at the burning of an effigy whose silhouette is remarkably human, and remarkably lifeless.

Thanks for this!

Like a religious relic, Hendrix’s burned guitar is framed and hanging on the wall at Rolling Stone. At least it was when I worked there years ago.