All Bad Music Will Eventually Disappear

Or how I learned to stop worrying about those godawful playlists

“No stupid literature, art or music lasts.”

That’s a quote from literary critic George Steiner (1929-2020)—in his highly recommended book Real Presences from 1986.

I was shocked when I read that sentence. But pleasantly shocked.

Could it really be true that all the sonic detritus circulating in our culture will just magically disappear? It seems too good to be true.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

And Steiner wrote that before the rise of the Internet and AI. If he thought we were drowning in crappy art back in the 1980s, what would he think now?

Around 100,000 songs are uploaded online every day. I can’t listen to more than a fraction of them, but almost every day I check out random new tracks on Bandcamp—and sometimes the process is painful.

Nobody can say that I’ve shirked my responsibilities as a music critic. In recent months, I’ve listened to death metal bands from Croatia who sounded like they were ready to bludgeon the entire population of Zagreb; incoherent Christian drone pop that only delivers the Good News when it’s finally over; entire albums of static, buzzes, burps, or toots; people singing to backup tracks, but apparently unaware that they are in different keys; and various home recordings that should never have left the basement.

It's an ugly job, but somebody has to do it. I occasionally find that rare gem, a self-produced needle of rare pointedness in the otherwise dismal haystack. That makes it all worthwhile.

But Steiner may be on to something. Most of the bad stuff disappears without anyone worrying about it. In fact, it disappears for that very reason—because nobody worries about it.

And the deeper I peer into the past, the more I see the same Darwinian trend. He called it survival of the fittest.

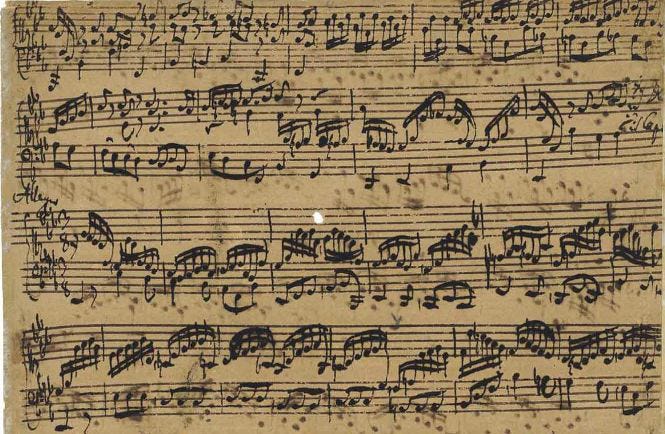

My considered judgment is that almost every musical work from the 17th and 18th centuries that survives in the standard repertoire possesses some merit. An interesting case is Bach, who is the presiding genius among the known composers from that era. Bach was unfairly forgotten in the years following his death—in fact, his sons got more acclaim than their dad.

Bach had been dead for more than 75 years before his reputation started rising again. The neglect was unfair, almost horrendously so. But with the passage of time, he gained preeminence, almost as if an invisible hand—much like those the economists describe—was setting things right. You could tell similar stories about other composers, from Antonio Vivaldi to Scott Joplin. It’s almost magical the way things work.

I must say that this is a judgment that takes a long time to make. Back at age twenty, I couldn’t have told you if Bach wrote better fugues than other composers, or Joplin composed better rags. Yet after decades seeking lost masterpieces from the past, and picking through the works of secondary and tertiary figures, I’ve concluded that the legendary figures from the past definitely earned their preeminence.

As a result, I worry more about the artists whose work has disappeared completely. Those are wrongs that can’t be rectified.

We see this process of sifting take place almost in real time. Consider the music of the early 1930s, when the most successful popular songs were goofy novelty tunes that kept people happy in the midst of the Great Depression. The biggest hit of 1930 was “Happy Days Are Here Again” by Ben Selvin, but that didn’t match the sales of his most famous song, “Dardanella”—which, by some accounts was the bestselling tune of the early decades of the twentieth century.

There are still people alive today, who remember those years, but Ben Selvin is already forgotten. Nobody puts “Dardanella” on their playlist. And for a good reason—it’s a piece of lightweight fluff. And the same is true of many other hit songs from the 1920s and 1930s.

In contrast, those amazing Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington recordings from the late 1920s and early 1930s not only have survived, but have a sizable audience almost a hundred years later—enough to generate millions of listens on the streaming platforms.

Nobody listens to “The Spaniard That Blighted My Life” by Al Jolson, a huge popular hit from 1913, but The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky gets performed constantly, despite being dismissed as too daring and demanding back at the time of its premiere.

Wendell Hall had the biggest hit recording in 1924 “It Ain't Gonna Rain No Mo’,” and was so famous back then that his wedding was broadcast live on the radio (the first time that ever happened). But his name is forgotten today, while George Gershwin’s much more ambitious work Rhapsody in Blue, from that same year, is beloved all over the world.

The same thing happened in the early 1950s, when record labels invested heavily in novelty tunes, sweet pop songs, and other shallow fare targeted at the mass market. Check out, for example, the top 20 songs at the end of 1952, according to Billboard:

"Blue Tango" (Leroy Anderson)

"Wheel of Fortune" (Kay Starr)

"Cry" (Johnnie Ray & The Four Lads)

"You Belong to Me" (Jo Stafford)

"Auf Wiederseh'n Sweetheart" (Vera Lynn)

"Half as Much" Rosemary Clooney

"Wish You Were Here" (Eddie Fisher)

"I Went to Your Wedding" (Patti Page)

"Here in My Heart" (Al Martino)

"Delicado" (Percy Faith)

"Kiss of Fire" (Georgia Gibbs)

"Anytime" (Eddie Fisher)

"Tell Me Why" (The Four Aces)

"Blacksmith Blues" (Ella Mae Morse)

"Jambalaya”(Jo Stafford)

"Botch-a-Me” (Rosemary Clooney)

"A Guy Is a Guy" (Doris Day)

"The Little White Cloud That Cried" (Johnnie Ray)

"High Noon" (Frankie Laine)

"I'm Yours" (Eddie Fisher)

At the risk of offending some ninety-year-old music fans, who danced to these songs at their high school prom, I must declare that this is not a distinguished playlist. I’m probably a bigger admirer of these artists than most of you, and even consider myself a fan of Jo Stafford, Rosemary Clooney, and Doris Day. But you’re still not going to find me listening to “Botch-a-Me” any day of the week.

But it doesn’t matter what I think—or what you think. These songs have disappeared from the public’s consciousness, and no critic had to lift a finger to make it happen. Meanwhile, the 1950s recordings by Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, and Charles Mingus will still be cherished a century from now, despite the fact that they were far too smart and ambitious to get on the Billboard chart when they were first released.

The bottom line is that bad music does seem to disappear—you just need to wait 70 or 80 years, more or less.

Why does this happen? I’d love to give credit to music critics like me—and I’m sure we play some role in this. But the musicians play an even larger part. There are tens of thousands of young musicians right now trying to learn from Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk, studying their recordings and performing their songs. Eddie Fisher might have been a huge star in his day, but today’s musicians are unconvinced of his centrality.

That’s how it works today. That’s how it’s always worked, going back to when Felix Mendelssohn launched the Bach revival, or even earlier.

And if you still believe that the canon is shaped by experts and critics, consider all the failures of the major prizes and awards. Almost half of the honorees of the Nobel in Literature, since its inception in 1901, are either already forgotten, or soon to be forgotten. The judges who give Nobel Prizes in Literature genuinely believe that they get to pick winners and losers in the larger culture—but their track record tells a different story. Again and again, they have honored obscure figures who enjoy a brief interlude of fame, then fall back into obscurity. Even a Nobel Prize can’t keep those reputations alive over the long haul.

And don’t get me started on the Pulitzer Prize in Music. Many of you are probably aware of my unhappiness over the fiasco back in 1965, when Duke Ellington was picked as winner by the music jury, but denied the honor by the Pulitzer board. More recently Pulitzer administrator Marjorie Miller has defiantly defended this crass and embarrassing decision. But there are other terrible missteps in the long history of the award.

But the bottom line is that, over the long haul, the Pulitzer has almost no influence on reputations. They can’t dishonor Duke Ellington, no matter how hard Ms. Miller works at it. Nor can they keep alive the forgotten music that they honored back in the day—a sizable portion of which never gets programmed by any major symphony orchestra. And for the simple reason that nobody wants to hear it.

Time relentlessly destroys almost every artistic reputation. Only a few works survive this brutal process, and they must possess some special merit—something far greater than a newsworthy award or favorable reviews—to gain the allegiance of posterity.

By the way, this is why I’m so skeptical of investors buying up the rights to all those rock songs from the 1960s and 1970s. A few of them will survive, and even generate meaningful income, but only the genuine masterworks of the era. So a portfolio built on Bob Dylan and Lennon/McCartney will be fine. But do you really want to bet on the market value of Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs (who had the top year-end Billboard song of 1965) or Lulu (the same for 1967) or the Archies (the same for 1969)?

But here’s where I address the elephant in the room. Although bad music will disappear, not all good music survives.

We all know this from our own lifetime—each genuine music fan of a certain age has seen deserving artists fall by the wayside. And if we could really dig into the full range of musical life from, say, the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries, we would probably have our minds blown by what got heard back then. Most of what was preserved comes from a few elite composers in a few cities in one small part of the world. Even if I love their works, I can’t help wondering what got left out of the music history books.

Let me make one final point.

This survey makes clear why music writers have a greater responsibility to write positive music reviews about outstanding works than negative hit pieces on bad music. The bad music will go away on its own. But good (and even great) artists often need a helping hand if their work is to survive.

I’m fully aware that this runs in the face of current attitudes. We live in a hardball culture, where takedowns and putdowns generate clicks. I see this every day on social media, where the nastiest attacks get the most likes.

There’s no reason why we need to emulate this in our musical culture. But I fear that we do so almost instinctively. The audience is thirsty for blood, so those of us who serve up opinions online keep throwing them red meat.

Just telling people to be kinder doesn’t seem to have much impact. But maybe the larger lessons of history—at least as applied to music and the arts—will have some impact.

Those lessons are clear: We don’t need to destroy the bad stuff, because there’s some kind of quasi-evolutionary process at work that will eliminate it anyway. But goodness is more fragile, and needs our support.

I’m absolutely convinced that’s true of music. But it just might apply to everything else too.

Your premise here hits close to home as a performing artist. Specifically as a tap dancer, the only dancing that survived the 20th century was whatever was filmed, photographed, or remembered in stories. Too many amazing dancers never made it into film and so their craftwork, body of work, and personalities are lost to history. Those who witnessed them kept memories alive, but often didn't have a place to put them, either. Some of the stories made it to print (as documented oral histories), but reading about dancing isn't the same as bearing witness to the dancing in real life. For years I've worked on trying to solve for this challenge: how do you support an oral tradition in a culture that isn't organized around oral traditions? Still working...in the meantime, thanks for the reminder that the good stuff lasts, precisely because people care about it, and to be an encourager of what is good, not just an identifier of what is bad. That's something I can do right now.

About twenty five years back I thought the low brow direction country and rap was heading wouldn't last, but it got much worse. So did just about every other genre overall. Since there has been a thing called the music industry things have never been close to as bad as they are now.

The masses are in a low state and resonating with music in a low state. Sure, good music will come back someday, but that day doesn't seem like it's anytime soon. Until the emotional intelligence of audiences improves the music and art overall will suffer. This is what a cultural gutter feels like. Tunes for Biff world brought to the real.