A Scandal Is Taking Place in American Music This Week

Mack McCormick's 'lost' Robert Johnson bio gets published after 50 years—and the story behind it is stranger than any of us suspected

A scandal is taking place in American music this week. And it’s all about a book written 50 years ago—and finally published on Tuesday.

The release of this work has set off arguments that, I suspect, will continue for decades to come.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

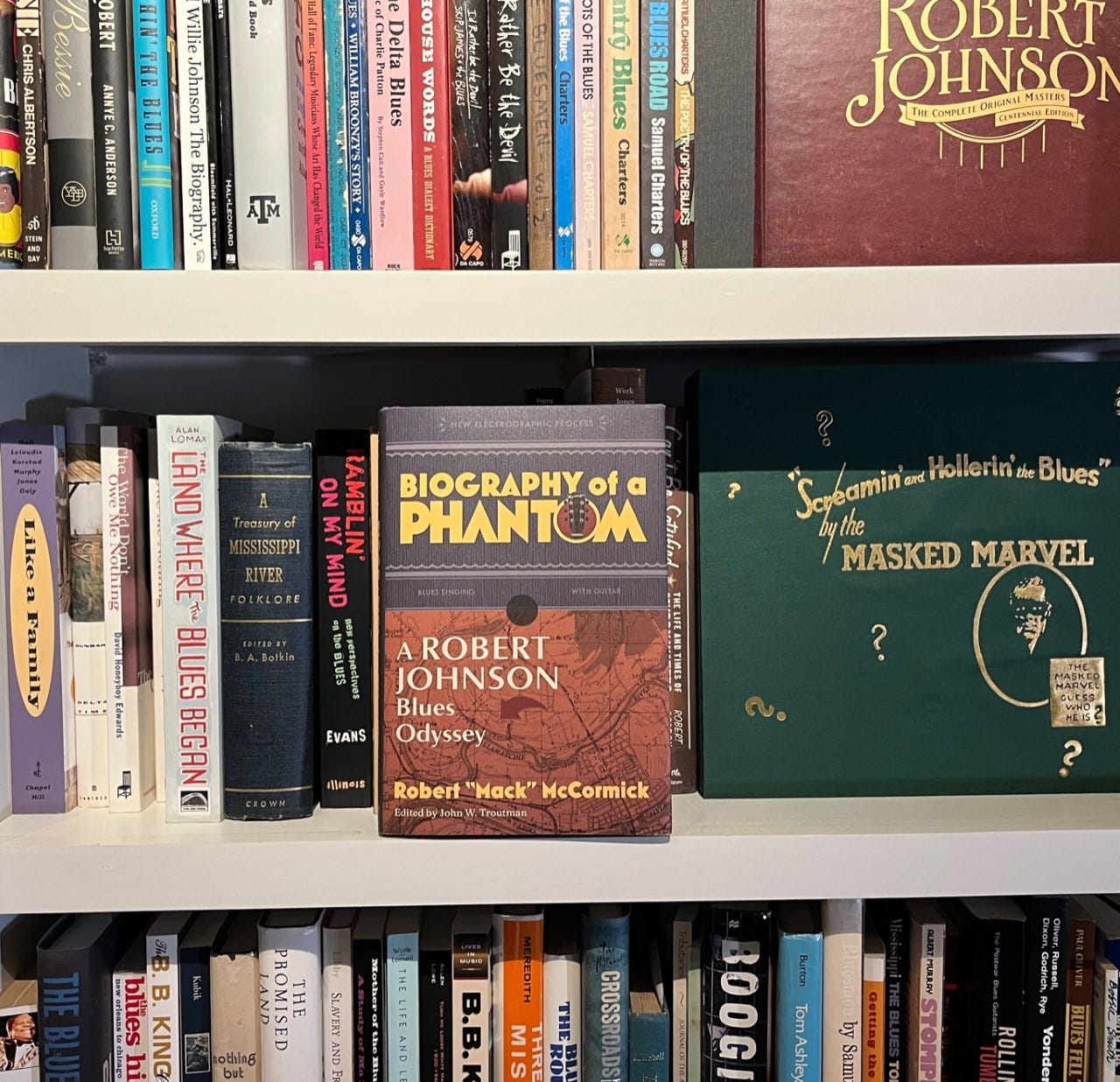

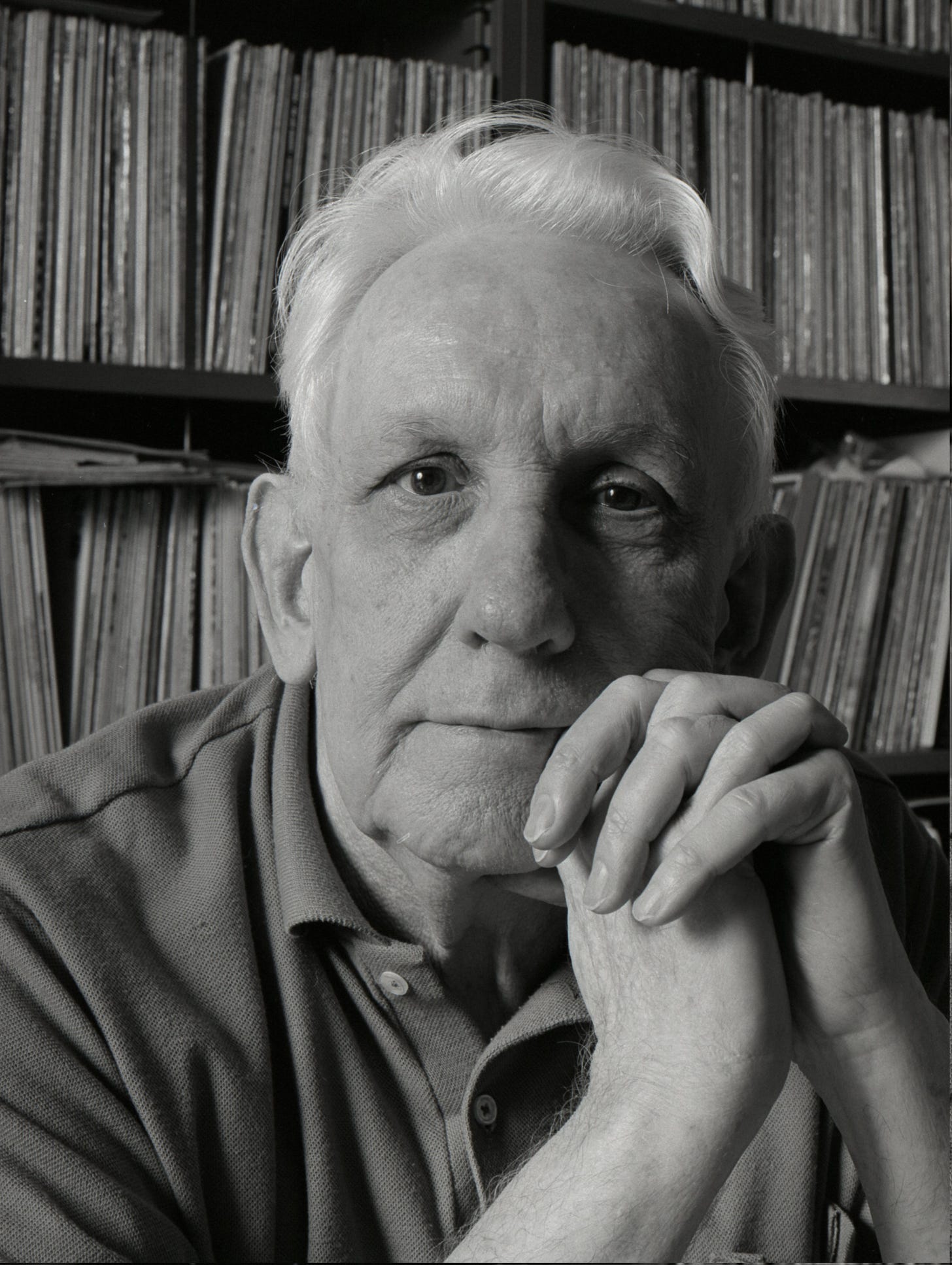

The book is the long awaited biography of blues legend Robert Johnson by the late Robert ‘Mack’ McCormick (1930-2015). Ever since it was announced a half century ago, this work has been eagerly anticipated by blues fans and music scholars—who hoped it would solve all the mysteries surrounding the most enigmatic figure in twentieth century American music.

Robert Johnson (1911-1938) profoundly influenced later generations of blues, rock, and folk performers—impacting everybody from Bob Dylan to the Rolling Stones. But what little we knew about his own life was more legend than reality. We heard crazy stories about him selling his soul to the devil, or showing up in unlikely cities under assumed names, or finally getting poisoned by a jealous husband who literally got away with murder in the racist South.

But it was hard to know what was true and what merely rumor or conjecture—until McCormick started making lengthy field trips into Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, and elsewhere, going anywhere or everywhere even a speck of information might be found. While others speculated about Robert Johnson, McCormick was determined to uncover the truth—at whatever the cost.

“Mack made an amazing revelation to Hall. He claimed that the Mississippi guitarist named Robert Johnson—admired all over the world today—didn’t actually make those famous blues recordings.”

He did most of this work in the 1960s and early 1970s—starting at a time when professors and career musicologists had little interest in undertaking this kind of laborious research into the origins of the Delta blues. The people doing the work were mostly blues fans like McCormick, and there weren’t many of them. But he was on a mission—almost like those ludicrous Blues Brothers in the movie of the same name—and through sheer bloody persistence eventually tracked down numerous people who knew the legendary musician back in the 1920s and 1930s.

By the time Mack was done, he had collected a whole archive of information from musicians, family, friends, and more than a dozen people who had witnessed or known of that fateful night when the famous guitarist stood up at his last gig, and announced “I’ve been poisoned”—and then fell to the ground.

McCormick began work on his definitive book, which he called Biography of a Phantom. It was a suitable name—because Robert Johnson was a phantom to almost everybody except McCormick himself, who had finally put together all the pieces of an amazing life story.

But the book didn’t appear in the 1970s, despite the author’s grand claims. Nor did it get published in the 1980s or 1990s or at any point in McCormick’s lifetime.

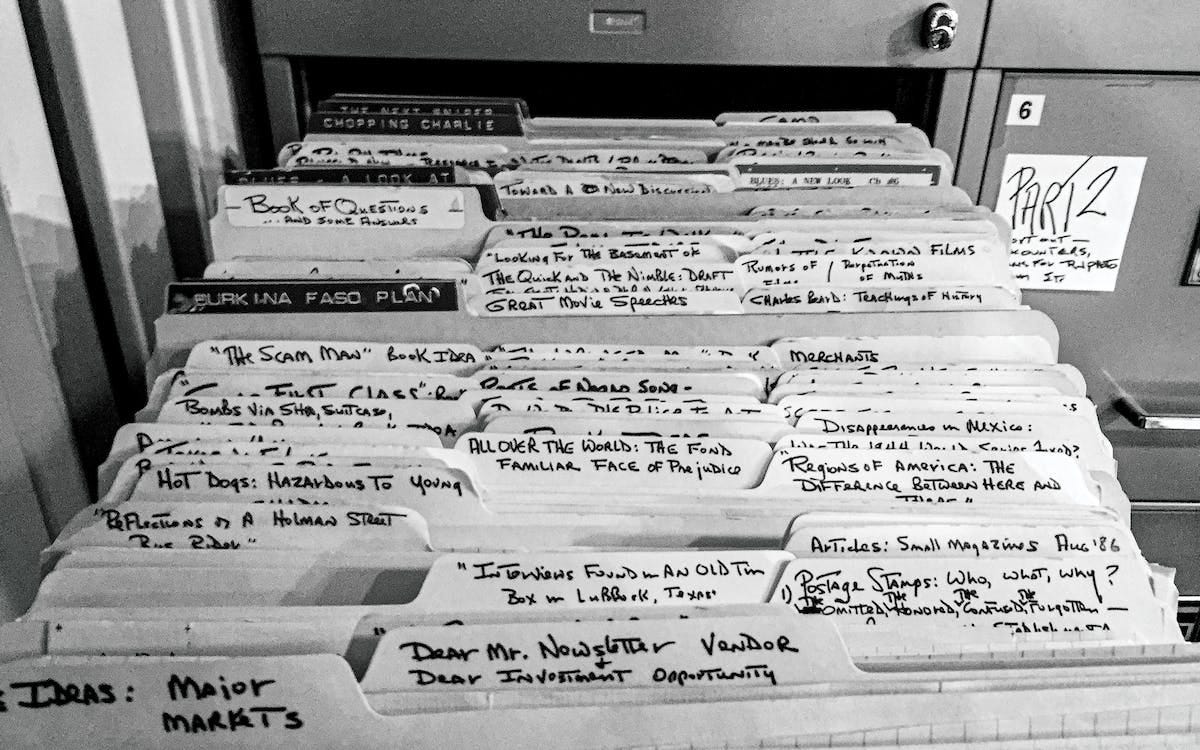

Finally, after the author’s death, his huge personal archive—known as “The Monster” because of its massive size—got acquired by the Smithsonian. This stash, which had previously filled the nooks and crannies of McCormick’s Houston home, included recordings, photographs, field notes, and various manuscripts, including different versions of the unpublished Robert Johnson bio.

In the aftermath, the decision was made to publish an early draft of the manuscript. And when it came out on Tuesday, all hell broke loose—at least in the world of blues research and American music history.

I am not a disinterested observer of this. I knew Mack. I liked him, and admired him for his smarts and dedication. I also felt sorry for him—because he was his own worst enemy. (I related many of these details recently at this link.) So my concern in this endeavor and the resulting ruckus is more than just scholarly.

Of course, this book and the issues it raises are much larger than my own loyalties and opinions. But my connections with some of the key players involved give me perhaps some useful perspective on the unfolding scandal. Many are asking what I think about all this—so I need to do the best I can to sift through the controversies and try to reach some conclusions.

On the very day the book came out, Mike Hall published an article in Texas Monthly on the peculiar details surrounding it. Mike had known Mack since 2001—and even got to see parts of the mysterious Robert Johnson bio when McCormick asked him to be his literary executor.

Hall’s article is a key part of all this, because it provides invaluable information that you won’t find in the book itself.

For example, Mack made an amazing revelation to Hall. He claimed that the Mississippi guitarist named Robert Johnson—admired all over the world today—didn’t actually make those famous blues recordings. In fact, the man we all honor as the ‘King of the Delta Blues’ didn’t record a single note.

Somebody else made that music.

Hall writes:

[Mack] said he was having serious doubts that the man whose trail he had discovered back in 1970—the Robert Johnson from Mississippi—was, in fact, the Robert Johnson who’d recorded those immortal songs in Texas. There was no proof, he said—no contracts, no letters….

It would make much more sense that the Robert Johnson who recorded in Texas already lived in Texas, was perhaps from Texas. Almost everything we knew about Robert Johnson, Mack came to believe—which is to say everything Mack had discovered about Robert Johnson—was wrong, because we were looking at the wrong Robert Johnson.

This seems bizarre—but it matches what Mack hinted to me in our conversations. He told me: (1) Much of what he once believed about Robert Johnson was wrong; (2) That other researchers were misled because so many people were named Robert Johnson in the Deep South, and more than a few of them were musicians; and (3) even the death certificate for the Mississippi Robert Johnson should make us suspicious (because, for example, it describes a “banjo player” when the musician on the records is a guitarist).

And this tangled web gets even more tangled: Hall makes clear that Mack might have been fabricating all this in his dealings with both of us. That’s because McCormick—as we now know—sometimes inserted false information into his writings and conversations.

He may have had legitimate reasons to do so, at least at first. Mack genuinely feared that others were intent on stealing his research—hence he could both identify and punish the culprit by means of these incorrect details. In other words, he was setting a trap.

But, over time, Mack started to believe his own fabrications. He was bluntly honest in telling me about his mental problems and bipolar disorder. And anyone who talked to him at length got a sense of his paranoia. But his problems went even deeper than this.

“The last ten years before my mother died and then afterward, he was living in a fantasy world,” Mack’s daughter Susannah told Hall. “Anything in the manuscript from the last twenty years is probably highly suspect.”

Maybe you are starting to see why this Robert Johnson book is turning into a scandal.

Alas, this story gets even more difficult to untangle—because Mack had good reasons to be paranoid.

Many other blues writers borrowed or stole his research materials, or used legal stratagems to block his work. When he told me that another blues researcher broke into his house or had his phone tapped, I knew this wasn’t very credible. But then a short while later, a writer for the New York Times actually published a celebrated article drawing on materials literally stolen from Mack’s home.

Sometimes the paranoid really do have enemies.

In the course of my research, I got to know most of the leading blues researchers from the 1960s and 1970s. The rivalries in this group were intense—I’ve never seen anything like it in any other field of study. Mack was very combative too, but the plain fact is that he was usually on the losing end of these battles. I don’t think he was always embittered, but by the time I met Mack in 2005, he was a defeated person—and painfully aware of it.

Of course, much of the blame fell on his own shoulders. He had a massive case of writer’s block that prevented him from publishing the fruits of his research. He was suspicious and distrustful—and this cost him the support of people who might have otherwise helped him. He didn’t follow through on promises (probably as a result of the shifts from euphoria to dysphoria associated with bipolar disorder), and this exacted a toll in lost opportunities and paydays.

But give the man a break, he was operating with mental illnesses that are well documented. In his favor, let’s acknowledge that McCormick did the arduous fieldwork others were too busy or lazy to undertake, and did it with an energy and devotion I can only admire. Again and again, he went on the road in pursuit of his quest—the roots of American music—with few rewards to show for it. In the final analysis, he got almost nothing for his troubles, except a reputation as a cranky, difficult man.

He deserves better. Mack McCormick was brilliant, one of the smartest music scholars I have ever met. The posthumous revelations have not caused me to alter that opinion.

I only wish that this Robert Johnson biography had been published by people more sympathetic to Mack and his work. The editor, John W. Troutman, is not sparing in his criticisms of McCormick—and of those other ardent blues fans who did almost all the early research into this music.

He believes they should have “invited” others to participate in their work.

But of course he must know few people had any interest in doing blues fieldwork in Mississippi in the 1960s and 1970s, and for a very good reason. There were no grants funding it, and little institutional support of any sort. To undertake blues field research in this situation was lonely work that often cost more than it paid. You could end up dead broke if you pursued this vocation with too much enthusiasm.

Troutman cites the case of Jim McKune, the supposed leader of this so-called ‘Blues Mafia.’ But it’s worth noting that McKune lived at the YMCA, where he kept his blues records in a box under his bed. He was later murdered. He had a sad life and was very much a victim—not an elite in any sense of the term.

The notion that McKune, or my friend Steve Calt (also mentioned here as part of the Blues Mafia) should have invited others to share in their opportunities and rewards leaves me dumbfounded. Calt often phoned me in his final days, as he lay dying and struggling with his near impoverishment.

Or consider the case of my friend Gayle Dean Wardlow, a pioneer of blues research who has made heroic contributions to our knowledge of this music—but at such a cost. To pay the bills, he worked as pest exterminator in the same neighborhoods where he did blues research. I wonder who he ought to have invited to participate in such a project.

Yes, it’s a scandal that others didn’t assist in this fieldwork. But the guilty parties are the large institutions who could have offered meaningful support. The brutal truth is that they didn’t give a damn. A few people—almost all of them obscure music lovers without impressive affiliations—took on this massive historical reclamation project out of love for the music. One was a high school dropout named Mack McCormick.

In contrast, John W. Troutman—according to the bio on the book—is a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. He holds three degrees, including a PhD.

I’ll let other decide who, among these various individuals, enjoys the perks of privilege and power, and can meaningfully invite others to participate in their projects.

Troutman, of course, had to make some hard choices in editing this material, and I don’t envy the difficulties he faced. He decided to rely on an early draft of the Robert Johnson manuscript, which was probably wise. The version he chose is well-written and engaging—with none of the turgid prose in the other posthumous McCormick book (on Texas blues).

Even more to the point, the published book deals only with the well known Robert Johnson from Mississippi—and offers no details on Mack’s later hypothesis that somebody else made this music. I believe that Troutman’s decision to rely on this draft, written before Mack constructed his alternative Texas lineage for the recordings, was the right choice, for reasons I lay out below.

Each chapter is filled to the brim with insights, new information, and powerful writing. McCormick clearly had high literary aspirations at this juncture in his life. I suspect that he was trying to capture something similar to Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, the most celebrated ‘true crime’ book of the era. McCormick presents himself in these pages as a musical detective on the trail of the most elusive guitarist in history, and successfully conveys all the uncertainty and suspense of his investigation.

That’s exactly how this story ought be told. Mack really was trying to solve a murder, and his sleuthing and forensic analysis are fascinating in their own right. As a result, readers not only learn about Robert Johnson, but also how his remarkable biography got extracted from the realm of myth and brought into the hard light of late twentieth century scholarship.

I read these chapters with excitement. But can we trust them. As noted above, Mack sometimes put false information into his own documents, and at a certain point may have started to believe his own fantasies.

My assessment is that McCormick’s falsehoods as a scholar date from a later period. I believe that this early manuscript is reliable, and reflects the author’s research at a stage when he didn’t worry much about people stealing his proprietary information. He just wanted to write a great book—and the end result here testifies to his capacity to do just that.

I can’t prove all that. But it’s my considered judgment.

He was a happier man, more confident and forthright in those days—and as you read through these pages, you feel how much he wants to get at the truth.

So I trust editor Troutman’s decision to publish this version of the bio, even without having seen the alternative drafts. I’m less pleased, however, at the decision to remove material Mack got from interviews with Robert Johnson’s sisters. It’s true that they decided later that it was better to assist a rival blues researcher—who promised them a better financial deal. But writers often get interviews from people who subsequently regret giving them. That’s fairly common.

And there’s no reason to believe that the sisters changed their mind because of any inaccuracies in their testimony. They simply decided to pursue a more lucrative option. That was their right. But also Mack had every right, as far as I can see, to publish what he learned from them.

I suspect that the excised material was significant. And though some information from family members was later published in other works, the earliest interviews in these kinds of situations are often the most reliable. I can only guess at what was lost because of this editorial decision—I hope it’s reversed at some later point.

Finally I need to address the wild notion that the real Robert Johnson was a Texas musician. Troutman hardly touches on this matter in the published version of Biography of a Phantom, and probably with good reason. He does mention in a footnote, that McCormick researched 31 individuals called Robert Johnson, and eventually focused on six leading suspects. But if McCormick had good reason to attribute the famous blues recordings to some new person, you won’t find it in this book.

I’m okay with that—because here’s what I think actually happened (in chronological order):

Mack undertakes laborious research into the most famous musician in Mississippi history;

He gets the help of the musician’s surviving family members; but

These family members ‘betray’ him, as he sees it, and cut a deal with a rival blues researcher;

Mack decides to get revenge, and does so by

Concocting a half-baked theory that none of these people were actually related to the ‘real’ recording artist; finally

Mack starts to believe his own unlikely theory.

Based on my firsthand knowledge of Mack, all this seems plausible—especially when you add the fact that the new Robert Johnson, in his fantasies, is a Texan. Mack was very proud of his home state, as Texans often are. The idea that these iconic performances were made by a resident of the Lone Star State must have been very appealing to him.

In the last few days, I’ve reconsidered my various conversations with Mack—where he kept hinting at his alternative ‘Texas’ theory. I can say with complete confidence that he wasn’t trying to deceive me. By this stage, he totally believed this wild hypothesis. That’s especially true when I consider our long conversations on the Robert Johnson death certificate. Mack was clearly amazed that I couldn’t figure out why it was a suspicious document.

At our first meeting, he handed me a photocopy of Robert Johnson’s death certificate over the dinner table (he had actually brought it to the restaurant), and proceeded to analyze the “38 facts about Johnson” one could deduce from it. Some months later, we talked about this document again, and here are my notes of that conversation:

Mack noted—as he had in our Houston meeting—that the facts on the death certificate would only have been known by a family member or a very close associate. Once again (as also at our meeting), he belittled the death certificate which—in his words—talks about the death of a “syphilitic banjo player.” At some times, McCormick seems to hint that the death certificate is not the death certificate of the famous blues musician. At other points, he seems to hint that the death certificate is really the famous musician’s, but was full of falsified information for “reasons that will make sense when I tell you.”

You can draw many conclusions from this, but one of them is how intensely Mack was studying the primary sources in his quest to prove his new theory. If he was fooling me, it was only because he had fooled himself. Even at this late stage, he still acted out his chosen role as a private investigator trying to solve a mystery—and nothing less than the biggest mystery in twentieth century American music.

But the mental anguish and self-delusions of the final years of McCormick’s life shouldn’t distract us from the remarkable manuscript that just got published. Mack was at the peak of his powers when he wrote these chapters and, against all odds and in the face of countless obstacles, had completed an extraordinary research project.

He learned things nobody could uncover today. And he put it down on paper with all the smarts and intensity he possessed in the prime of his life—and before all the later disappointments.

It’s a shame that he lost the thread, and went off on other tangents instead of publishing this ‘true crime’ story back in the 1970s. But the end result here is a significant book, even if it took a half century to see the light of day. All the scandals and inevitable arguments, shouldn’t distract us from that fact. Let’s hope there’s more in that ‘Monster’ archive, but this publication alone goes a long way towards validating my friend’s life work.

Troutman sounds like an entitled gas bag. I've lost more money writing about the blues than I've ever made off it.

Daved Honeyboy Edwards knew and toured with Johnson, and lived 70 years after his murder. If that wasn't Johnson on record, Edwards would have known.

Plus, Edwards' repertoire drew upon many of the same songs Johnson recorded.

You are such a gifted writer, and so thoughtful and insightful in your assessments of others (what drives, haunts, or limits them). This wasn't a topic I thought would have interested me, but I should have known that you would utterly capture my imagination by the end of the second paragraph.