30% of Children Ages 5-7 Are on TikTok

And why did youth mental health problems accelerate after 2010?

In recent weeks, I’ve published a series of articles on “dopamine culture”—the fast-paced scrolling and swiping behavior promoted by Big Tech.

I’ve argued that they are doing this to instill addictive behavior. These interfaces operate like slot machines at a casino, providing a dopamine boost every few seconds. The goal is to keep users’ eyes glued to their screens—thus maximizing advertising revenues.

The leader in this movement is TikTok. But the other major platforms (Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, etc.) are imitating its fast-paced video reels.

My articles have stirred up discussion and debate—especially about the impact of slot machine-ish social media platforms on youngsters.

So I decided to dig into the available data on children and social media. And it was even worse than I feared.

If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a premium subscription (for just $6 per month).

30% of children ages 5 through 7 are using TikTok—despite the platform’s policy that you can’t sign up until age 13.

The story gets worse. The numbers are rising rapidly—usage among this vulnerable group jumped 5% in just one year.

By the way, almost a quarter of children in this demographic have a smartphone. More than three-quarters use a tablet computer.

These figures come from Ofcom, a UK-based regulatory group. I’ll let you decide how applicable they are to other countries. My hunch is that the situation in the US is even worse, but that’s just an educated guess based on having lived in both countries.

What happened in 2010?

One thing is certain—the mental health of youths in both the US and UK is deteriorating rapidly. There are dozens of ways of measuring the crisis, but they all tell the same tragic story.

Something happened around 2010, and it’s destroying millions of lives.

Now let’s look at the timeline for global smartphone usage. This also accelerated around 2010.

Apologists for TikTok will tell you that these mental health problems are merely correlated with excessive screen time and that does not prove causation. Well, yes, of course, but…I will simply ask you to judge the plausibility of that defense based on your own common sense observations and life experiences.

Their defense would be more plausible if youngsters were spending only a small portion of their day online. So let’s look at more data on how they allocate their time.

As early as age 11, children are spending more than four hours per day online.

Here’s a comparison of time spent online by age. Even before they reach their teens, youngsters are spending more than four hours per day staring into a screen.

Here’s what a day in the digital life of a typical 9-year-old girl looks like.

I don’t find any of this amusing. But if you’re looking for dark humor, I’ll point to the four minutes spent on the Duolingo language training app at the end of the day. This provides an indicator of the relative role of learning in the digital regimen on the rising generation.

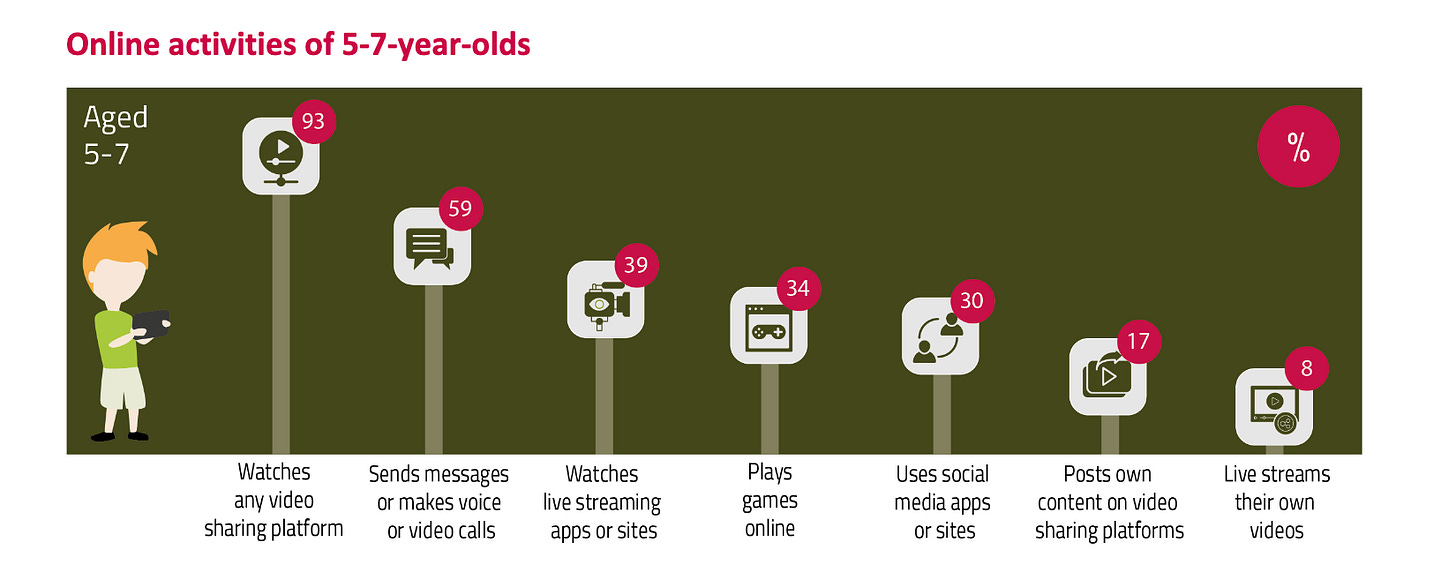

Even five year olds are immersed in streaming and scrolling interfaces.

Now let’s look at even younger children. Here’s a glimpse at the digital life of a child aged 5 through 7.

Around 20% of five year olds have their own phone, and almost all children do by age 12.

The role of digital media increases dramatically between ages 8 and 12.

By the way, more than 20% of underage users have an adult profile which allows them to access all content on these platforms.

What could possibly go wrong?

RELATED ARTICLES:

I Ask Seven Heretical Questions About Progress

The State of the Culture, 2024

I Receive a Letter from a High School Student

Notes Toward a New Romanticism

Thirteen Observations on Ritual

How to Break Free from Dopamine Culture

Skeptics can pretend this is all quite normal. But, judging by the feedback I’m getting, the vast majority of adults have already lost trust in the technocracy. They are deeply troubled by what the dominant platforms are doing to society, especially vulnerable children.

They know that a terrible crisis is underway, and blame tech leaders and their apologists—who are destroying the next generation in pursuit of profits.

We’ve seen it before. There was a time when tobacco companies denied that smoking caused cancer. (Their argument—that correlation does not prove causation—will sound familiar.)

That was too bad for all the people who died because of that smokescreen argument (literally and figuratively). There was also a time when corporations—and the US government!—issued propaganda to support the use of DDT and other dangerous pesticides. We’ve seen the same narrative spinning in so many other business: asbestos, automobiles, opioids, etc.

But you should always follow the money.

Academics who defended smoking took big cash from Big Tobacco. You should check out how much tobacco money went to distinguished statisticians back then—who would ever have guessed that these STEM academics could be corrupted by cash?

I believe we are at a similar juncture right now.

We will eventually have access to peer-reviewed, longitudinal studies with tightly defined control groups. Along the way, statisticians getting funded by tech, and their fellow travelers, will try to obfuscate as much as they can. But wise parents—who live in the real world, not academia—are already taking prudent steps.

That’s what parenting is all about.

It would be nice if the government and tech billionaires (now lining up to buy TikTok) helped them out. But since so much money is at stake, parents will probably have to fight this battle on their own.

The rest of us should support them as best we can. A good starting point is to speak honestly and forthrightly about what tech is actually doing in our communities. I’ll certainly be writing more about this in the future.

I did some graduate research on this recently. It isn't just kids and it isn't just smartphones. Above a certain threshold of moderate usage, time spent using electronics is negatively correlated to well-being for adults as well.

Pretty sad. In that graph for that girl nowhere did I see reading as an activity.