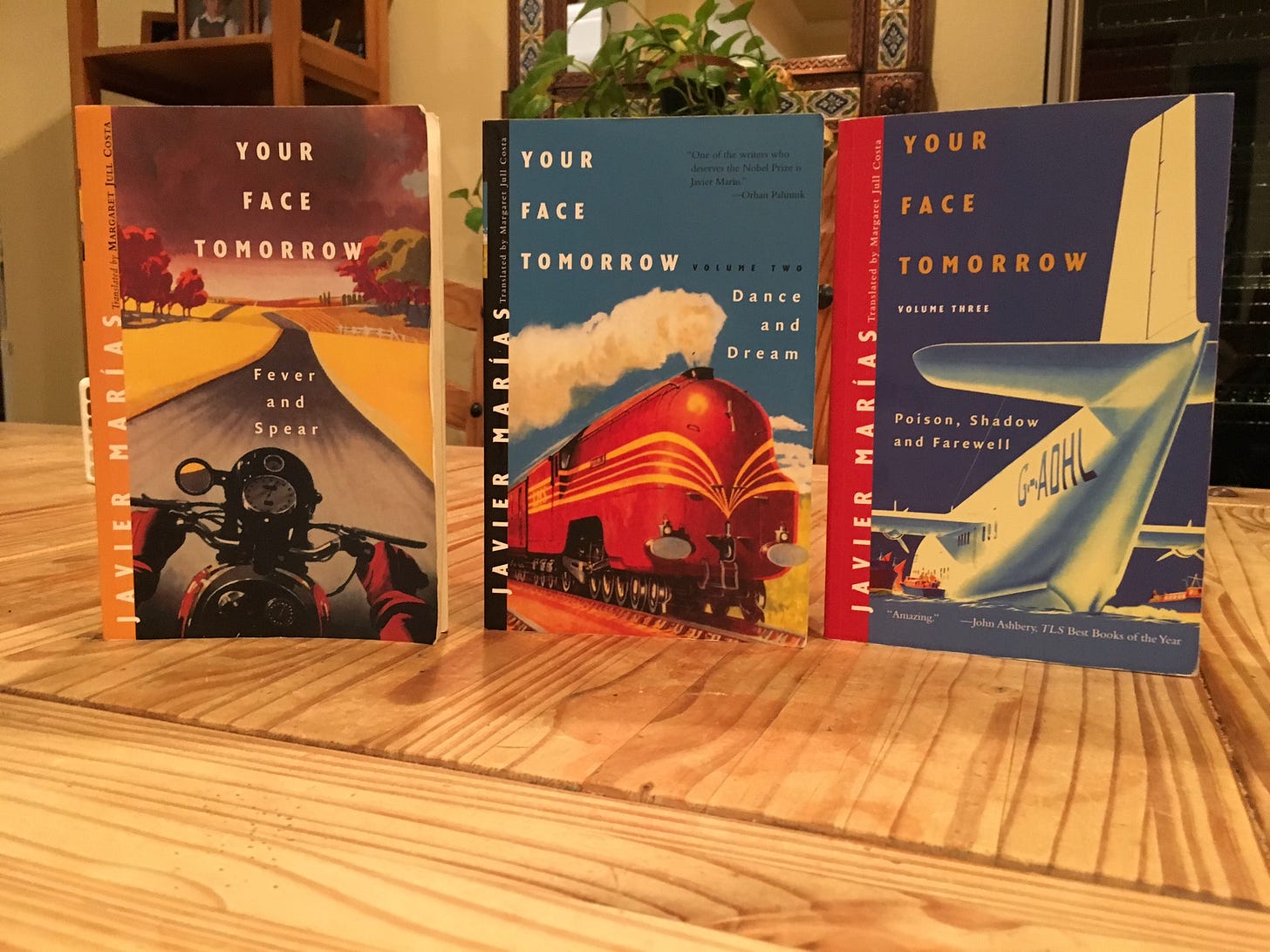

Your Face Tomorrow by Javier Marías

Javier Marías's Epic 1300-Page Novel of Existential Espionage Is Unlike Any Other Spy Novel You Will Ever Read

Let me cut to the chase—something Javier Marías rarely does during the course of this 1300-page novel in three volumes. Here’s the bottom line: This is one of the best novels I’ve read in the last decade, the smartest, most moving, most stimulating. But it’s not a novel for the faint-hearted or those who seek pleasing escapism from stories that operate, as so many do nowadays, as Freudian wish-fulfillments or prepackaged moral lessons or theme-park-style thrill rides. Your Face Tomorrow is not that kind of book.

But if you are a reader who, like me, feels that novels have been corrupted by cinema, TV and video, that narratives in the current day too often dwell on surface images rather than the riches and complexities of the inner life, the domain which fiction is best suited to address, then you should make the acquaintance of Javier Marías. He is a kindred soul, and a fearless one. He isn’t afraid of dissecting psychological nuances with the precision of Henry James, of probing existential depths with the courage of Fyodor Dostoevsky, or constructing long, lapidary sentences as ambitious as those of Marcel Proust. None of those approaches are fashionable in the new millennium, and that, I dare say, is simply one more reason why you should read Your Face Tomorrow.

Marías, however, is sly and knows how to lure you into his story, even as it deviates from the tricks of the popular fiction trade. He even gives his existential story the trappings of an espionage novel, with spies and counterspies, adventures and betrayals, crimes and secrets. When the final volume of Your Face Tomorrow appeared in English in 2009, the New York Times likened it to a John le Carré thriller, and that’s not an inapt comparison. But that reference tells you much about the moral dimension of Marías’s approach. Le Carré’s spies stands out from their peers not so much for their wiles and intrigues but for their corrupted, quasi-Nietzschean worldviews that blur the line between good and evil, heroism and nihilistic power politics. The same is true, but even more markedly, with the secret agents who serve their even-more-secret masters in the world of Javier Marías.

Another spy novelist appears in the pages of Your Face Tomorrow, namely Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond. Our narrator Jacques Deza, a Spanish intellectual living in England, is surprised to find Fleming’s personal inscription in a book owned by his friend Sir Peter Wheeler, an aging Oxford professor. In a first edition copy of From Russia With Love, discovered by chance on the professor’s bookshelf, is written: “To Peter Wheeler, who may know better. Salud! From Ian Fleming 1957.” Deza finds other signed books from Fleming on the shelf, and is puzzled that his friend never told him that he knew the famous spy novelist.

Is Wheeler hiding his own secret history as a spy? He now seems little more than a retired academic, but looks are deceiving. More to the point, he sees special talents in our narrator Deza, and enlists him to join a secret espionage unit that works in a “building with no name” in London. In fact, even the organization itself lacks a name—or if it has one, employees haven’t been told. By the same token, they are left in the dark about who they are serving.

Deza is hired because of his special ability to observe people and analyze their characters and propensities on the basis of tiny details others might miss. (There’s an unstated irony that permeates these pages: The qualities that are supposedly crucial in espionage are actually those more often possessed by novelists than actual spies—in particular, an ability to connect personality with emblematic traits, possessions, gestures, phrases, and quirks.) Deza’s skill is all the more valuable because, as Wheeler laments, so few people in the current day are able to see what’s staring them in the face, let alone anticipate how people might behave tomorrow or the day after. Because of his gifts, Deza can serve the agency as an interpreter of people, a predictor of lives, an anticipator of an individual’s face tomorrow.

Here’s the passage in which the spy recruiter explains to Deza why such abilities are so rare—and marvel how Marías simultaneously builds his espionage story, demonstrates his own skill at interpreting people, offers philosophical insights and provides a trenchant critique of contemporary society.

“The times have made people insipid, finicky, prudish. No one wants to see anything of what there is to see, they don’t even dare to look, still less take the risk of making a wager; being forewarned, foreseeing, judging, or heaven forbid, prejudging, that’s a capital offence, it smacks of lèse-humanité, an attack on the dignity of the prejudged, of the prejudger, of everyone. No one dares any more to say or to acknowledge that they see what they see, what is quite simply there, perhaps unspoken or almost unsaid, but nevertheless there. No one wants to know; and the idea of knowing something beforehand, well, it simply fills people with horror, with a kind of biographical, moral horror. They require proof and verification of everything; the benefit of the doubt, as they call it, has invaded everything, leaving not a single sphere uncolonised, and it has ended up paralyzing us, making us, formally speaking, impartial, scrupulous and ingenuous, but in practice, making fools of us all, utter necios . . . Necios in the strict sense of the word, in the Latin sense of necius, one who knows nothing, who lacks knowledge, or as the dictionary of the Real Academia Española puts it . . . “Ignorant and knowing neither what could or should be known.” Isn’t that extraordinary? That is, a person who deliberately and willingly chooses not to know, a person who shies away from finding things out and who abhors learning.”

And here’s another passage, perhaps even more insightful, almost a kind of touchstone for grasping the zeitgeist:

“The present era is so proud that it has produced a phenomenon which I imagine to be unprecedented: the present’s resentment of the past, resentment because the past had the audacity to happen without us being there, without our cautious opinion and our hesitant consent, and even worse, without our gaining any advantage from it. Most extraordinary of all is that this resentment has nothing to do, apparently, with feelings of envy for past splendors that vanished without including us, or feelings of distaste for an excellence of which we were aware, but to which we did not contribute, one that we missed and failed to experience, that scorned us and which we did not ourselves witness, because the arrogance of our times has reached such proportions that it cannot admit the idea, not even the shadow or mist or breath of an idea, that things were better before. No, it’s just pure resentment for anything that presumed to happen beyond our boundaries and owed no debt to us, for anything that is over and has, therefore, escaped us.”

Perhaps you are unmoved by such passages, or—maybe even more likely—resent them the way Marías’s necios resent the past. For my part, I am dazzled by an author who can employ this kind of hermeneutic thinking to advance a plot about master spies embattled in international intrigue. Whatever your response, you are unlikely to encounter another book quite like this one.

Deza joins the secret agency, and soon makes a contribution with his abilities. But a contribution to what? The level of secrecy is such that he can never be quite sure who he is helping, who he might be hurting. He can’t figure out whether he is working for “the navy, the army, such-and-such a ministry or one of the embassies, or Scotland Yard or the judiciary or Parliament, or, I don't know, the Bank of England or even Buckingham Palace.” He eventually learns that, in a zeal for outsourcing, his work might even be helping private individuals with deep pockets, and maybe they have criminal interests or—it can’t be rule out—even foreign governments antagonistical to his own. And what is his own country? Is it Spain, where Deza was born? Or Britain where he now works? Or should his allegiance be simply to himself and his personal interest?

This ambiguity is troubling, but becomes more so as his job starts to result in acts of violence. Deza prides himself on his moral compass, strengthened by the lessons taught by his father who survived, barely, the betrayals and bloodshed caused by the Spanish Civil War. Yet the son who once thought that he instinctively did the right thing, now learns that he is capable of the same kinds of irresponsible actions that caused so much tragedy for his family and forebears.

This is a deeply moral novel. I tell you that with trepidation, because I know how such books are viewed by many readers, who have been inundated with moralizing stories. There’s a difference, a rather sharp one. This book doesn’t give you predigested lessons aimed to manipulate your behavior. If you want that, there are plenty of other stories out there to deliver it. Marías’s trilogy is a moral work in the best possible way, namely because it forces you consider your own decisions and indecisions. Even better, it prods you to think what your own face might reveal tomorrow, what you might be capable of doing, to your later regret, when placed in a situation where ends seemingly justify means and conformity to the group agenda is imposed with strict discipline.

Reading this book, I’m reminded of a talk I gave once to a group of medical school students who were interested in the humanities. I was asked what benefit a future doctor or other professional might get from reading literature. I told the students the following: “At some point in your career, you will almost certainly be asked to do something unethical. I have even worse news for you: the person asking you to do this will probably be your boss. And here’s the worst news of all: When this happens, you will probably have no more than 30 seconds to make a decision.” We read literature, at least in part, to learn from the experiences of others and, in a pinch, to make better decisions when put in such difficult situations.

I hadn’t read Javier Marías when I gave that talk, but I probably would have cited this work specifically if I had known of it at the time. I will look for other occasions in the future to tell people to read it. For a start, I’m taking the opportunity to do so right now.