You Don't Need a Mentor—Find a Nemesis Instead

In which the author expostulates on his odd notions about sports, music, and life

On three different occasions I considered writing a book about sports. Are you surprised? Well, so am I.

I’ll be the first to say that these ambitions were ridiculous in almost every way. I’m no expert on sports. I’m not even an especially passionate sports fan. I tune in, and tune out—and sometimes I’ll go weeks without paying any attention to rankings and competitions.

But each of these ideas captured my interest because they felt much bigger than sports. They appealed to me in my guise of a cultural critic—which, on certain days of the week, is how I view myself—and especially because they were each so rich with implications for everyday life.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

I’ll never write these books, but in the spirit of George Steiner—who once wrote an entire book about the books he never got to write—I want to share these three concepts, and then explore one of them (what I called my nemesis project) in a little more depth.

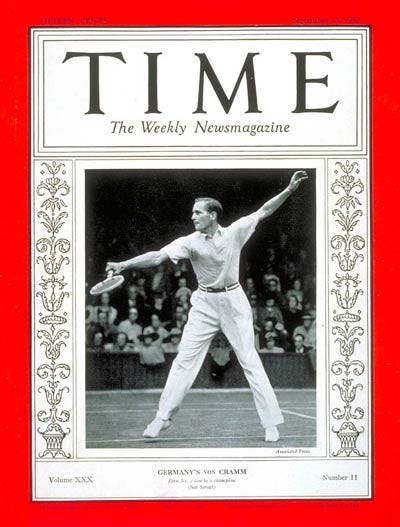

The first of these unwritten books seemed very simple, at least at first glance. It would have been about sportsmanship. The opening chapter would have focused on an extraordinary moment at the 1935 Davis Cup, when Baron Gottfried von Cramm refused to take a match point that would have given Germany victory over the United States—because he claimed his racket had touched a ball before it went out-of-bounds.

It was an error that no one else saw, including the umpire. No one would have ever known about it. But the Baron felt there was something more important than winning. When the German captain denounced him as a “traitor to the nation,” von Cramm responded: "On the contrary, I don't think that I've failed the German people. In fact, I think I've honored them."

The story is rich with implication, and would make a great opening gambit for a classroom discussion, and not just about sports. But I was especially interested in the idea that the rules of the game aren’t absolute guides—that sometimes there are even higher rules that must be consulted. Philosophers call this natural law, but it’s usually treated as some abstract theoretical concept with little bearing to everyday life. My inquiry into sportsmanship would have shown how the most powerful laws are those we impose on ourselves, and how each of us understands intuitively—even a youngster in a sporting competition—that there are some standards of behavior that are even more binding than the written rules and guidelines.

I never wrote that book, and it’s probably no great loss. I didn’t have the expertise to deal with the subject adequately, without devoting years of research to it. But I still believe that sportsmanship is the single most neglected concept in all of athletics. You can listen to sports talk radio for a year, and not even hear the word mentioned once. Yet it ought to be part of our everyday dialogue about any sphere of life involving intense competition.

The second sports book concept actually morphed into music research. I have long been interested in how rituals and performances enact violence symbolically in order to defuse actual bloodshed. Sporting events are the most obvious examples of this, but musical performances achieve very much the same function. That’s why there’s so much symbolic violence—performers destroying their instruments, and then later trashing their hotel rooms, etc.—in popular music. Those who have read my recent book Music: A Subversive History will recognize how deeply I was influenced by this line of thinking.

So I also have no regrets that I never wrote that second book on sports. I got more benefit by applying that conceptual framework to my study of music.

But then we come to my third sports book concept, and this is one that still preoccupies me. It has to do with what sportswriters and fans call rivalries. But I view it as something different—I refer to this same phenomenon as the Concept of the Nemesis. And I have a hunch that it is one of the most powerful and underrated driving forces in human behavior.

I believe that my Nemesis Concept even explains key developments in music and the arts. A recent study of composers during the period 1750-1899 discovered that they were significantly more productive when they lived in close proximity to other composers. The most likely way of accounting for this, to my mind, is the inherent rivalry that arises when creative people encounter each other daily.

I’d even guess that the extraordinary impact of New York on the history of American music is partly explained in the same way. New York musicians are highly competitive—did you know that?—much more so than the West Coast players I dealt with during my formative years. Growing up in LA, I found that the geography was so spread out that musicians could operate in quasi-isolation, only encountering their peers at the rehearsal or gig. This wasn’t always a bad thing. The sprawling nature of SoCal urban development allowed for a greater degree of creative freedom and independence—allowing many experimental or avant-garde musicians to develop in Los Angeles (Ornette, Dolphy, Cage, Mingus, etc.) without having to worry about the groupthink or prevailing norms. But that came at the cost of cultural intensity. New York, in contrast, possessed that intensity as an inevitable result of its population density—three times as great as LA’s—which puts musicians in frequent contact with one another. In other words, it’s much easier to find your nemesis in Manhattan.

Even after I gave up on my idea to write a sports book about the nemesis, I pursued at some length the idea of turning it into a novel. I wrote more than 30 thousand words of it, before setting it aside.

I often begin a book project by designing an imaginary cover. Here was the cover for my never-finished nemesis novel. I won’t even begin to explain the plot (for which you should be grateful). It’s based on an actual historic figure, who briefly appears as a character in Gabriel García Márquez’s fiction and autobiography, but deserves an entire book of his own.

So don’t ask me about all the strange dealings in this book—which begins with everybody in the world spouting halos and ends with a duel in front of Google’s headquarters. But I will describe my ideas about the nemesis, which plays such a key role in the text.

The first thing to understand is that your nemesis is not your enemy. Or, put differently, your nemesis is more than just an enemy. Rather, the nemesis is an adversary is who is like your dark twin. Even as you battle with the nemesis, you share a kind of DNA. The gaze at your nemesis is like looking into a mirror, but one of those fun house mirrors at the carnival, where everything is both recognizable and distorted.

In every way, this relationship is more powerful and volatile than a battle between enemies. I even sensed that as a child when I read comic books. The Superman stories were shallow because he never faced a true nemesis, he merely dealt with pathetic villains, and even the best of them—Lex Luthor, for example—could never compete with the Man of Steel on his own terms. That’s why they needed to rely on dirty tricks (usually involving Kryptonite) to weaken him, and make him as pathetic as they already were.

But Batman was a different story entirely. Batman had a true nemesis in the Joker—and even a child could see the genetic resemblance. They both wear strange outfits. They both had bad childhoods. They both operate outside the law. They are both unhinged. They are both obsessed with gadgets. They both are shameless media hounds. And both of them desperately need to get laid, but it will never happen because they refuse to get out of their costumes.

They need each other. They complete each other. They hate each other, but also have a repressed attraction to each other.

You can’t find a richer or more multifaceted relationship. Not even between a married couple. I feel sorry for Robin, who will never rise beyond the sad pay grade of sidekick. The Joker is the real target of Batman’s passions and obsessions. That’s why movies featuring that remarkable nemesis have earned more Oscar nominations than all the other superhero films combined.

But this is more than just a matter for filmmakers. All great societies were built on the fruitful conflict between a hero and a nemesis. Think of Cain and Abel in Judeo-Christian culture or Set and Osiris in Egyptian mythology. Look back to the origins of Roman preeminence in the conflict between Romulus and Remus.

As mentioned above, artists often benefit from identifying a nemesis. Art history is full of examples—Constable and Turner, Michelangelo and Raphael, Brunelleschi and Ghiberti, Picasso and Matisse, etc. For example, the inspired daub of red paint in Helvoetsluys by J. M. W. Turner was allegedly inspired by the painter’s desire to outshine his rival John Constable when both were participating in the same exhibition.

And in science and technology you have just as many examples: Edison and Tesla, Newton and Leibniz, Jobs and Gates. Even now Musk and Bezos are engaged in a ludicrous space race that must reflect some personal animus between these two very similar rivals.

And then we come to sports.

As I mentioned above, I’m not a huge sports fan. But that changes when a nemesis is involved. That’s rarely a term used by sportswriters, who talk endlessly of rivalries. But those who see these encounters up close have no doubts about what’s really involved.

After the Lakers lost to the Celtics in the 1984 NBA Finals, Magic Johnson stayed in the shower for a full 30 minutes—allegedly weeping—before meeting with the press. His teammate Michael Cooper later tried to explain what had happened: “Not only did we lose to the Boston Celtics, but [Magic] had lost to his nemesis Larry Bird.”

Johnson himself also understood that to defeat his nemesis, he needed to become more like him—something mere enemies never feel. “I learned a valuable lesson. Only the strong survive. Talent just doesn’t get it. That’s the first time the [80’s] Lakers ever encountered that, someone stronger minded.” A year later, Magic and the Lakers beat the Celtics—but only because they learned from their nemesis.

That’s the fastest way to discover whether someone is an enemy or a nemesis. People always want to stress how different they are from their enemies. You don’t even want to get them started on the subject, because they won’t stop. They will enumerate all of the enemy’s terrible character traits and failings—making sure you know how different they are from that awful person.

As I look back at a lifetime of watching sports, the moments I truly cherish always involved this kind of mirror-image relationship between competitors. So I will always prefer watching Magic-versus-Bird over those Michael Jordan highlight films—even though I realize the sheer superiority in athleticism of the latter. Without a nemesis, Jordan could win championships, but he couldn’t create the kind of Greek tragic drama of the encounter with the other.

The first time I experienced this was as a child, when Ali battled Frazier in three titanic boxing matches that will, in my opinion, never be surpassed. Maybe there have been better boxers—I’ll let the aficionados of fisticuffs debate that—but if you’re seeking out the encounter with the nemesis, those two boxers achieved something of almost archetypal dimensions.

I got a brief glimpse of the same phenomenon in the extraordinary confrontation of middle-distance racers Sebastian Coe and Steve Ovett. But, sadly, they only met each other on the track seven times. But I know that I’m not the only one who would shell out money for a pay-per-view if they raced again nowadays as old men. No, not because they would be especially fast—that won’t happen again—but because they embody the encounter with the nemesis at the highest possible level.

“I was prepared to die with blood in my boots for the 1500 meter,” was Coe’s later description of his mindset. Ovett described their races as his “duel” with someone who was “bullet-proof.” Many years later, the two rivals had dinner together and discovered how much they had in common. Some might be surprised, but no one who has deeply considered the true nature of the nemesis.

When else have I experienced the joy of the nemesis in sports? In tennis, Nadal versus Federer is the obvious example. Serena and Venus Williams could have been on that level—and here they actually share the same DNA, not just symbolically but biologically. Yet I don’t think they were willing to view each other as the nemesis, so this never took off as a rivalry. McEnroe might have been able to achieve something similar with Borg, but his character made him incapable of grasping the essence of the nemesis. For McEnroe, all the people against him were just enemies—and with that mindset he could never truly rise to that high destiny. And it’s probably why Borg won Wimbledon five years in a row, and McEnroe could only repeat once.

In contrast, the totally dominant athletes—Tiger Woods, Tom Brady, etc.—fail to capture my imagination. They might very well be unsurpassed at what they do, but they’ve never had a nemesis, and so I really can’t be bothered. At best, they treat their own past achievements as benchmarks. But if your only nemesis is your younger self, your life will inevitably follow a downward trajectory.

I believe there are useful lessons here for all of us—and not just high-performance athletes. First, you need to take care in deciding who plays the role of nemesis in your life—and if you don’t have someone like that, you might be missing out. Because your nemesis will teach you things that no mentor can. The nemesis can push buttons you didn’t even know were there to be pushed. The nemesis may bring out the worst in you, but if you manage the situation effectively, also the best.

Next, be sensitive to the true nature of the people who cause problems in your life. I have reached the realization that some of my fiercest critics have picked me out as their nemesis. They never consulted me about this—in fact, they’re usually people I’ve never met face-to-face, but that’s probably why I’m able to serve this role in their psyches. If we had met, I might have turned into a mentor. At least, that’s how I prefer to view the dynamic at play. This doesn’t necessarily make me want to run off and have a beer with them. But I do grasp that the true nature of our relationship is richer than meets the eye. If I just viewed them as enemies or fools, I would miss out on the opportunities for growth that their confrontations provide me with.

Let me make one last point—and in this instance I want to return to the larger issue of sports with which I started this essay. Athletic competitions have tremendous potential for building character, but it is almost entirely misused at the present juncture. I could cite many examples and reasons, but I hardly need to—just read the sports news for a few weeks, and you will see how sadly we fall short.

Instead of using competition as a means of self improvement, we have turned it into a platform for every kind of dysfunctional behavior. And, worst of all, this starts in all the youth sports leagues, where a sick kind of Darwinian eat-or-be-eaten mentality predominates. There are exceptions, and they are inspiring. But in a culture that celebrates winning at all costs, and making as much money in the process, they are hidden from view.

So I regret not writing my three books, not because I would have done such a good job with them—I probably would have fallen far short of my aspirations, all things considered—but merely because the message was the right one. At the forefront of that first unwritten book was the notion that sportsmanship deserves to be as celebrated as winning. I still believe that passionately. Second was the idea that violence in sports ought to be a way of defusing the violence in society; and that’s also still a core personal value so many years later. But that last unwritten book had the biggest lesson of all, namely that we really don’t need to make enemies in our life—it’s much better to find (and learn from) your nemesis. And even the enemies we think we have might not really be all that different from ourselves.

Those aren’t just lessons for athletes, but sports would be a good place to begin putting them to work. Then maybe the rest of us would start paying attention too.

Quite possibly your best so far –– and you have had a pretty high batting average as it is!

Excellent essay.