Why Were Execution Ballads So Popular in Europe?

For hundreds of years, these songs circulated widely, and were even sold at the gallows—for reasons that are sadly still relevant today

TRIGGER WARNING: I’ve never put a trigger warning on an article before. But, hey, you saw the headline. And these kinds of songs are frequently censored nowadays. So proceed with caution.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Why Were Execution Ballads So Popular in Europe?

I often hear hit tunes about partying, romancing, dancing, and various kinds of group solidarity. You can even climb the charts with songs about martial arts or a bordello in New Orleans or what’s going to happen in the year 2525.

But how about an execution?

Capital punishment may seem an unlikely subject for a hit song. But a few hundred years ago, execution ballads not only circulated in society, but were extremely popular.

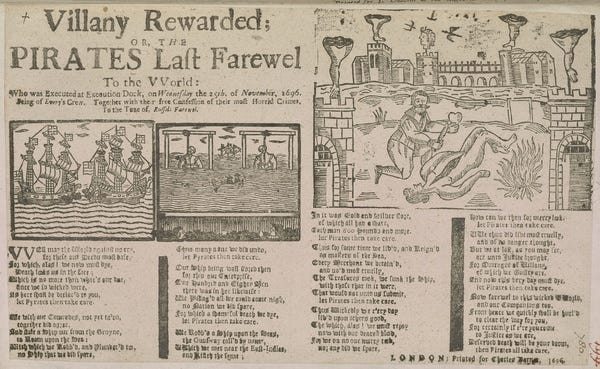

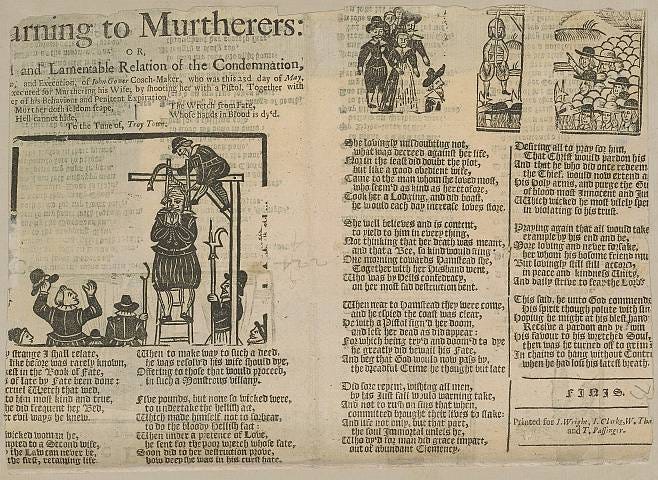

The music business, as it existed in those days, depended on these bloody songs for profits. Countless examples survive in the form of broadside ballads—popular songs that were printed and sold and performed in public spaces.

They were often sold at the execution itself. But they continued to circulate in the following days—serving as a combination of macabre entertainment, moral education, and daily news for people who hadn’t actually been in attendance.

Back when I wrote my book on the history of the love song, I learned that many people are embarrassed to admit how much they like sentimental songs about romance. We all know the lyrics to hundreds of sappy tunes, and could even sing along if we wanted—but who dares, except in private? But the execution ballad is even more shameful than a sentimental love song. And music writers have, accordingly, preferred to avoid this unsavory subject.

I am a peculiar exception—and not because I like violent songs. I really don’t. But starting back around 1990, I decided that I wanted to learn the genuine and honest history of music as it impacted the everyday life of individuals. This was a momentous turning point in my vocation, although I didn’t recognize it at the time.

With the benefit of hindsight, I have to say I had no idea what I was setting myself up for—the music of everyday life, over the centuries, was much darker and disturbing than I had ever imagined. My course of study soon required that I learn about murder ballads, execution ballads, and a bunch of other genres that don’t make much traction on the Billboard charts nowadays.

I have occasionally written about this subject—for example in this article on “the deadliest song in history.” That song is called “Fortune My Foe” and it was sung at executions, and in other ugly situations. In fact, if you had bad news to share back during the day of Shakespeare, you would often sing it to this melody. As soon as people in the town square heard those familiar opening notes, they would gather around to find out what terrible thing had happened this time.

In other words, it was sort of like Twitter for the village people. (No, not those Village People—we’re talking Renaissance village people.) They kept up with current events through songs. Execution ballads went viral, in the parlance of the current day.

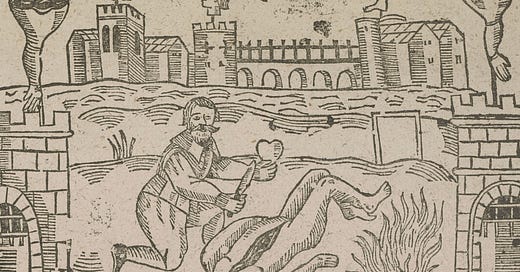

That may sound like an absurd comparison, but it really isn’t. The old execution and murder ballads were published with familiar illustrations, that were used again and again. These pictures were the first visual memes—and they circulated along with the songs themselves. The fact that these ballads also repeated the same melodies over and over added to the meme-like nature of this early form of media.

This type of remix was a lot like TikTok—relying on familiar tunes and illustrations to grab an audience’s attention—but a whole lot darker.

I am happy to report that we now have a definitive book on the subject of the execution ballad, a new in-depth study by Dr. Una McIlvenna, who teaches at the Australian National University. Her book Singing the News of Death, recently published by Oxford University Press, is not just smart but brave, tackling a disturbing subject that has too long been left in the shadows of music history.

As McIlvenna makes clear, these songs are extraordinarily relevant in our own time. I have already called attention to how the old ballads established the viral meme. But they are also forerunners of a host of other cultural phenomena—from fake news to first-person video games to reality TV.

This is why we have no right to dismiss the execution and murder ballads with the smug superiority of people who have risen high above such tawdry and degrading entertainment.

Because we haven’t.

The illustrations in these printed ballads are certainly disturbing, but hardly achieve the level of graphic violence found everywhere today in movies, TV shows, and interactive games. The clumsy narratives of the execution ballads can also be mocked for their predictable and bloody formulas—but is that any different from the nine Nightmare on Elm Street movies, featuring disfigured serial killer Freddy Krueger, which have generated a half billion dollars in box office receipts? Or what about the 12 films in the Friday the 13th series? Or the 12 films in the Halloween series, another slasher franchise?

Modern audiences are no different from their Renaissance counterparts. They abandoned the execution ballad not because they’re more sophisticated or evolved, but merely because they found more intense substitutes. Otherwise they would still sell things like this on the street corner.

The British execution ballads are the best known, but this kind of song could be found throughout Europe. In fact, the last place to give them up was France, a nation that has never lost its taste for unpredictable street violence.

The French continued to hold public executions until 1939, and kept singing about it until that late date. For a long time, these brutal spectacles took place in market squares or other visible locations, and only gradually got moved to the environs of the prison. (The death penalty in France wasn’t abolished until 1981.)

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the execution ballad, especially in its English form, was the reliance on first person narratives in the lyrics. As strange as it sounds, these story songs are almost always told in the words of the murderer about to be executed.

This may seem like intense realism, but was actually the opposite. The murderer’s account was filled with moralizing comments that aimed to reinforce the values of the spectators. The goal wasn’t historical accuracy or objective news coverage but ideological reinforcement—although this, too, perhaps reminds us of media and entertainment tendencies of other times and places, including our own.

Take, for example, the case of Susan Higges who, dressed as a man and, carrying a knife, robbed people on the highway back in the 17th century. In the ballad, we hear her lament:

To mourne for my offences, and former passed sinnes,

This sad and dolefull story, my heavy heart begins:

Most wickedly I spent my time. devoide of godly grace:

A lewder Woman never liv'd, I thinke in any place.

This demand that the criminal apologize in the course of the song—and hence legitimize the execution—reminds me of Foucault’s observation, in Discipline and Punish, that Western societies originally focused on punishing the criminal’s body, but eventually became more obsessed with the offender’s mind. The audience for this music thus craved statements from the accused that combined acceptance of guilt, apology, and implicit support for the system that executed them.

Once again, we may be shocked and disgusted over this manipulative behavior. Those bloodthirsty onlookers must have known that the song featured a contrived apology, inserted only to conform to the audience’s comfortable worldview. But the blunt fact is that our own culture is equally obsessed with demanding apologies of all sorts, and in every possible setting—whether sincere or otherwise. If you look carefully around you, you will see that a refusal to apologize is often more upsetting to the public than the original infraction.

Foucault was right. We rarely demand punishment of the body anymore—many of us find that distasteful and would eliminate it entirely from the penal system. But we insist on the most stringent conformity in the offender’s words and attitudes, whether formally in the court and parole hearing, or informally in interviews and social media posts. That’s far more satisfying than caning on the buttocks, or locking up on the stocks—pastimes that appealed to our distant ancestors.

These execution ballads are invaluable in documenting the emergence of that now dominant mindset—combining, as they do, images of the physical punishment with words emphasizing moral submission. In the modern world, the former shocks us but the latter never goes out of style.

Finally, I want to point out that this long chapter in music history makes clear how much songs are impacted by the zeal for ritualized violence. This is a line of thinking I’ve drawn from the writings of literary critic and philosopher René Girard—a figure who, curiously enough, never wrote about songs, but whose work has strongly influenced my own views on popular music and popular culture.

I write about this unsavory matter not to call out contemporary hypocrisy—although that’s always a satisfying pursuit. I’m more interested in (1) pointing out how these old execution ballads are among the most revealing documents of their time, and (2) showing how relevant songs of this sort are even today—and for precisely the reasons that lead many to ignore them as too disturbing. We still need our scapegoats, as Girard tells us—we just pick them and punish them in different ways now.

But these songs are disturbing. So I don’t expect them to show up on the syllabus of a college music course. Yet they rank among the most illuminating and thought-provoking songs in the history of Western culture—and with implications far beyond the field of music.

Much of what got expressed back then in ballads now shows up on Twitter and other social media platforms. We don’t really sing about violence anymore. But that’s merely because we have plenty of it elsewhere. And I don’t doubt for one moment that it would get a lot of clicks if we did.

'Hang down your head, Tom Dooley........'

I can still remember the first time I heard the song "Weila Waila" as performed by the Dubliners. The lyrics perplexed me, as they sounded like essentially "murder lyrics" in spite of having a beautiful play on words (the chorus is "A Weila Weila Waila" which is ancient Gaelic for "a way by the waters").

I was too young at the time to know that this was one of the Child Ballads -- stories of crime and punishment -- that served the purpose of telling the general populace, in a gruesome reminder, that crime does not pay. Today, we have "crime dramas" that serve the same purpose: "Law and Order" and its many spinoffs provide that same reminder, alongside numerous other social issues that the creators wanted on the public conscience. Like the Execution Ballads, these were never "scientific" in execution. They were art. But they were a very utilitarian device educating the public.

One aspect of your article that intrigues me: the focus on issues other than realism. I know the execution ballads lacked a lot of that, and now, thanks to your article, I know why. Yet I would argue the same is actually true today: even "Law and Order" never shows police breaking certain rules, planting evidence, or refusing to go after political allies, for instance. They often include "moralizing" elements, and *certain* rule-breakers are allowed -- but they are usually sympathetic or glorified. Producer Dick Wolf has spoken highly of the NYPD, for example, and his work does get lots of procedure and courtroom politics correct -- but certain issues that are rampant within today's precincts are largely absent from his works.

I have looked for modern police literature in recent years, and honestly, the genre itself is often rather lacking, focusing on authors who tout their own experiences in law enforcement, or "thriller" writers who are more focused, as you say with the Execution Ballads, as first-person accounts of horrors that, again, aren't so much realistic as capable of providing shock and entertainment for readers.

It's a peculiar consistency, now that I compare them. And honestly: if it hadn't been for your article, here, I probably would not have even realized it.