Why Love Songs Are Badass

And how to read Sappho

I spent ten years researching and writing a book about love songs.

I learned many things, but two facts stand out:

Everybody knows hundreds of romantic love songs, and can even sing along—because the words are deeply embedded in our memory.

Most people are extremely embarrassed about this, and don’t want anyone to know.

You can’t deny it. Every one of you knows the words to a bunch of sentimental, icky-sweet songs—but would hate to admit it to your friends.

By the way, you will probably retain these lyrics in your memory at the very end of your life, even after you have forgotten so many other things. That’s how powerfully we are attached to this music.

If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (for just $6 per month).

Music critics are especially ashamed of love songs. Ninety percent of pop songs are about love, as critic Dave Hickey pointed out, but critics prefer to write about the other ten percent.

The ultra-hip critics will tell you that love songs are wimpy. But, of course, they know these songs, too—and can also sing along with all the words.

There are many reasons for this shame. But the biggest one, I believe, is that love songs remind us of our vulnerability—especially sad love songs. They are incompatible with macho stances or ultra-hip poses.

I point out, for what it’s worth, that my dear friend Scott Timberg, who committed suicide shortly after his 50th birthday, was researching a book about breakup songs at the time of his death. We often spoke about this topic in the final weeks of his life. I now think this was an expression of his own sense of the fragility and vulnerability of life.

It’s a simple fact that, when you sing these love songs, you feel exposed. Very exposed.

But I believe that’s the only way to sing them. And this must take an emotional toll, at some level, on the singer. I’ve felt it in my own life when I have sung these songs for a public audience. It’s almost painful to open myself up that much to total strangers.

The first time I did it on record, it only happened because the producer insisted. He heard me singing a love song in a private moment at the piano, and insisted that we put it on tape.

When I listen to this, it still makes me feel uncomfortable. It’s not that I don’t dig the track—I absolutely do—but still it seems strange that intimate expressions of this sort are put on the marketplace for public consumption.

Yet that’s how we roll in the modern world.

Here’s my simple advice to singers: If you don’t feel that vulnerability, you’re not singing these songs correctly.

Yet all this is very paradoxical.

That’s because I learned, while researching my book Love Songs, that this music is not wimpy. Not at all. Love songs are the toughest, most battle-hardened music in the history of the world.

The singers of these songs have been criticized, censored, cursed, physically attacked, sometimes even killed.

That’s because the love song is inherently disruptive, and even political. It expresses our deepest feelings in public—and this is always linked to freedom of speech, human rights, and personal autonomy.

New ways of singing about love have always been a cause of social change. That was true in ancient times. It was true at the dawn of the Renaissance. It has been true in our own lifetimes—just talk to people who participated in the Summer of Love or the Stonewall uprising, or in other liberation movements.

This brings me (finally) to the subject of the Greek lyric singer-poet Sappho, who is showcased in week two of my 52-week humanities immersion program.

Some of you are reading Sappho this week. That’s an easy assignment, because very little of her work has survived. I believe that is a measure of how much ancient authorities feared songs of personal emotion.

Sappho did more than anyone to legitimize this kind of expressive song in Western society. But it’s hard for us today—surrounded by love songs—to grasp how radical and in-your-face this was at the time.

Even after she set this example, the authorities resisted her influence. Lyric poets were taught to focus on praise songs about powerful men.

Until very recently, anyone who studied Greek lyrics was taught to imitate Pindar, who lived about a century after Sappho, and preferred to sing about military leaders, athletes, and other impressive dudes. Sappho, meanwhile, was a subject for slander and gossip.

As a result, very few lyrics by Sappho have survived in their entirety. You could read them all in less than a half hour. Meanwhile Pindar’s surviving works fill up five volumes in the Loeb Library of ancient literature.

As a result, this bias against love songs persisted for many long centuries. If Dave Hickey (cited above) is correct, the bias continues in our own time.

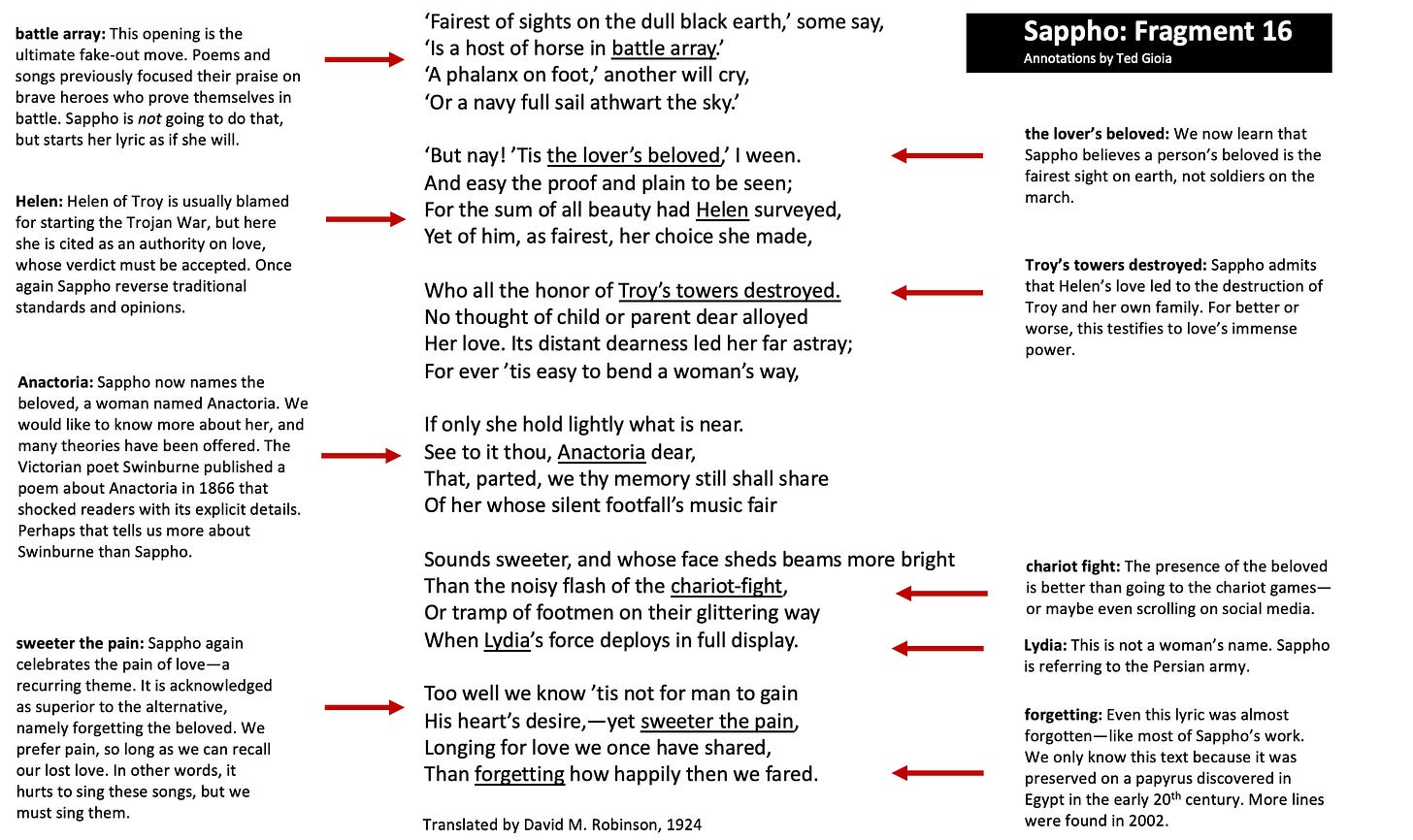

To guide you in this week’s humanities reading, I share two of Sappho’s most famous poems. It’s no exaggeration to say that these represent the essence of her work—because there’s not much besides them in a complete, coherent form.

I chose older translations in the public domain, but you should feel free to seek out other versions—which can easily be found online.

I’ve offered a few notes in the margin, to guide you.

Below is fragment 31—some have claimed that this is the single most important lyric from antiquity. Just understanding this one short text will give you valuable insights into how our concept of the singer-songwriter first emerged.

Now let’s move on to fragment 16:

If you simply pay close attention to these two lyrics, you will have a good sense of Sappho’s significance, and the role of the love song in human culture.

If you see connections with those sappy love songs we all know (but won’t admit to), don’t be surprised. They all link back to this ancient innovator.

Hi Ted. Love the substack and have benefited so much from your music writing over the years. Listened to the Havels the other night—divine!

You might want to check out a book I wrote, The Penguin Book of Greek and Latin Lyric Verse, for translations of Sappho, Pindar, and many others. Here’s my version of Sappho 31:

https://www.literarymatters.org/1-1-sappho-31/

C

Your comments on vulnerability reminded me of Ethel Waters' description of singing "Stormy Weather": "When I got out there in the middle of the Cotton Club floor I was telling the things I couldn't frame in words. I was singing the story of my misery and confusion, of the misunderstandings in my life I couldn't straighten out, the story of the wrongs and outrages done to me by people I had loved and trusted. Your imagination can carry you just so far. Only those who have been hurt deeply can understand what pain is, or humiliation."

"I sang Stormy Weather from the depths of a private hell in which I was being crushed and suffocated."