Why Is the Oldest Book in Europe a Work of Music Criticism (Part 2 of 2)

Here's the conclusion of chapter one of my new book 'Music to Raise the Dead'

Below is the conclusion of chapter one of my new book Music to Raise the Dead. In the first installment, we discovered that the oldest book in Europe, the Derveni papyrus, is actually a musicology text—but containing a very unusual approach to music.

The anonymous author of this controversial work made grand promises for certain hymns and their explications—which offer a pathway to a different plane of existence. You can interpret as an enhanced mind state, an alternative universe, a higher pathway amid your everyday activities, or even the afterlife.

Strange as it sounds, this is the origin of music criticism.

We are inclined to laugh at such outrageous claims nowadays. We have all heard of alternative universes, but do they really have anything to do with songs? Yet as I’ll show below, and in later chapters, this body of knowledge has influenced huge spheres of our culture, even areas we think have nothing to do with music—law, philosophy, science, religion, medicine, etc.

You’re skeptical, I know. How can our legal code be an extension of musicology? But it is, as you will discover, and many other disciplines too. Even more relevant, for our purposes, this esoteric science of song has survived into our own time—but it remains mostly hidden from view because it’s frequently disguised in coded utterances.

And, for a start, it’s certainly not taught at music schools. At least not yet—but that could certainly change.

So much for preamble. Let us proceed. . .

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

CHAPTER ONE

Why Is the Oldest Book in Europe a Work of Music Criticism (Part 2 of 2)

By Ted Gioia

To our way of thinking, all this makes no sense.

Why would musicians need to use codes? Do they expect the rest of us to be codebreakers? Why would Irish bards, for example, devote years to studying advanced cryptography? What could they possibly have to hide? Weren’t they esteemed members of their community and representatives of a venerable, respected tradition?

But you can’t really grasp what’s going on until you understand that even these respected elders were in constant danger. We’ve already seen how much at risk musicians have been throughout history, especially the most daring ones. Celtic bards were no different, and had to exercise extreme caution. As custodians of forbidden lore going back to prehistoric times, the Irish traditional singers pursued a risky vocation in a Christian society that had already eradicated the Druids for similar pagan beliefs and stories. If the bards spoke openly, their lives were genuinely in danger.

And now fast forward to 1956, when Sun Ra gave John Coltrane a Derveni-type document called “Solaristic Precepts”—which included a very similar coding system. And how did Coltrane react? Did he laugh at Sun Ra, the way others did? No, not at all. Coltrane studied “Solaristic Precepts” and distributed copies to other musicians. He also started taking on a more expansive approach to his own work—which eventually led him to adopt cosmic terminology as song titles and spiritual symbols. The transformation was so extreme that, shortly before his death, Coltrane even proclaimed that his new goal was to become a saint.

We shouldn’t be surprised by this—the old codes never went away. Eventually the bardic tales of Celtic culture entered the mainstream of Western society, but only because the singers had taken such care in giving them a veneer of Christian respectability. Yet behind the superficial orthodoxy of the resulting Arthurian romances—the most influential body of quest narratives in the history of Western culture—dark coded messages of musical origin still lurk, and are well worth studying. Like Sun Ra’s seemingly crazy pamphlet, these Arthurian narratives are surprisingly congruent with the Derveni papyrus—a document no bard could have read or knew existed (not even Sun Ra when he wrote “Solaristic Precepts”), if only because its uncovering in Derveni didn’t happen until 1962.

Scholar Henry Louis Gates has called this use of coded language signifying—and it plays a prominent role in many African-American traditions too, perhaps most famously in the old spirituals where political and social commentary existed in coded form behind religious songs. But signifying of this sort never stopped, and survived all the way to the blues and hip-hop songs of modern times.

Gates, too, traces it back to ancient myth and folklore, the African trickster in this instance, instead of the Greek Orpheus. But it’s very much the same thing. Orpheus, according to the Derveni author, used his music to tell “momentous things in riddles”—in other words, he too was a trickster with a code. And the more deeply we probe this subject, the more clearly we will see that the same complications and controversies raised by the Derveni papyrus are part of the oldest musical traditions found in every region of the world.

We may never know exactly why the Derveni papyrus was set on fire—the owner (or heirs) may even have been honoring the document by placing it on the funeral pyre. But I note that there’s a well-known quote from Euripides about honoring Orpheus with the “smoke of many writings.” Although that’s usually taken as a dismissive commentary on the ambiguity of these ritualistic texts, the evidence from Derveni suggests that burning these works might actually have been part of the ritual.

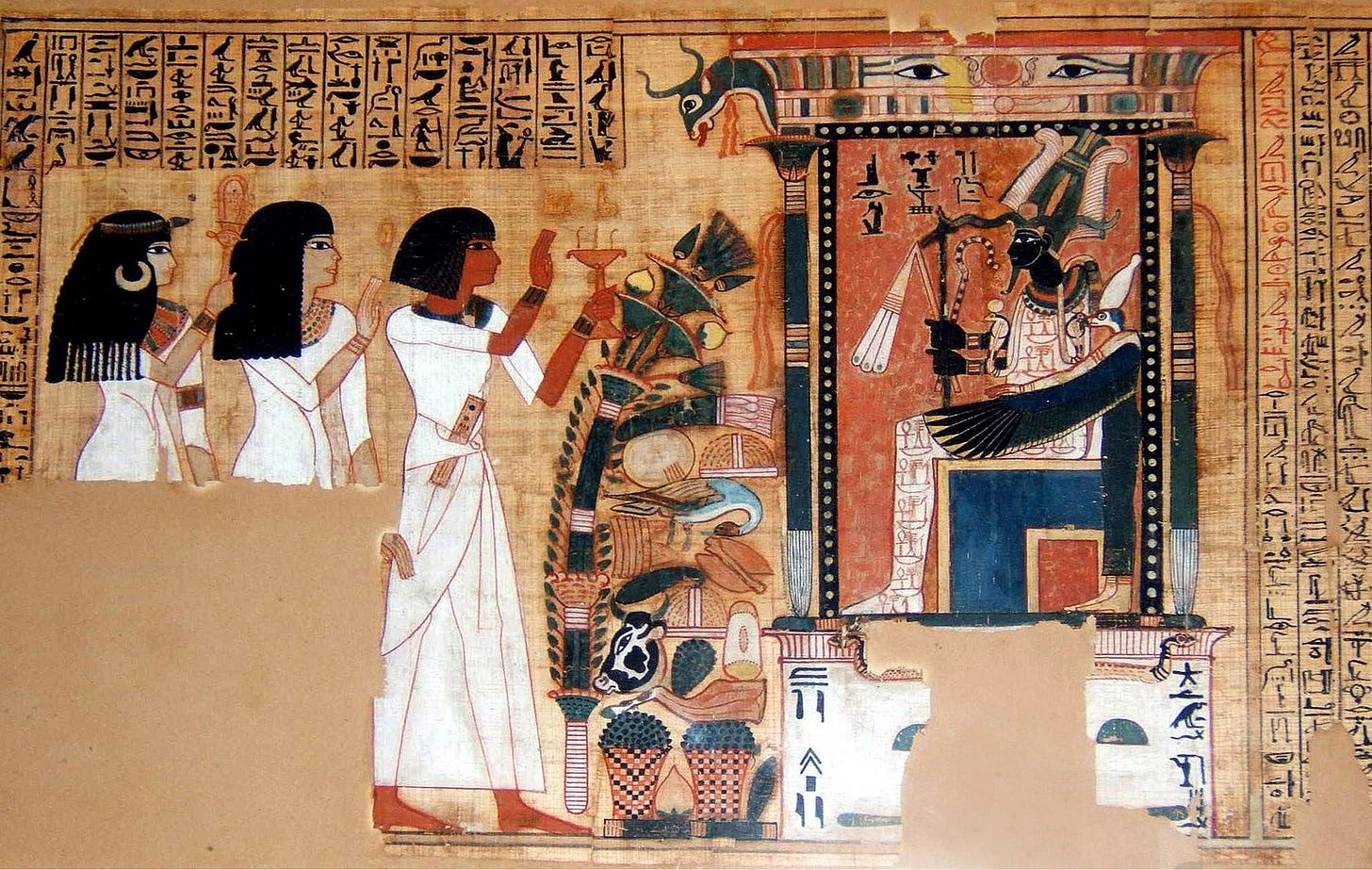

Put another way, the dead have their own quest journey ahead of them in the next world, and what could be more useful than a guidebook? Those familiar with the Egyptian Book of the Dead are well aware of how much care was taken in providing these travel itineraries for the world beyond. (And it’s perhaps not irrelevant that ancient lore about Orpheus often claims he learned his craft in Egypt—and Sun Ra, by the way, also mixed a heavy dose of Egyptology into his Afrofuturist musical manifestos.) This also helps us understand why this ancient musicology was so intense and vehement—knowing the right songs might determine whether you end up in a heaven or a hell.

It’s no coincidence that much of our source material on the followers of Orpheus comes from those who mock and satirize them, and very little from the ritual practitioners themselves; or that information about the songs survives in fragments or has been filtered through the views of those hostile to Orphic beliefs. Those obstacles are all too common whenever we want to discover the music that exists outside the dominant power structure, or as part of what we would call today a counterculture. The real oddity here—a miracle even—is that this firsthand account of an actual musical magician openly aligned with Orpheus survived at all.

As with any counterculture, this one was not designed for mass consumption. Musicians usually want as large an audience as possible for their songs, but the Derveni author makes clear that both the hymn and its interpretation are for the few, not the many. We take this outsider status for granted nowadays, and honor people (especially musicians) who resist mass-market pressures. But it took thousands of years before any singer operated in defiance of the status quo without paying a stiff penalty—at a minimum, the eradication of every song that refused to toe the line.

Even a gentle song expressing a personal emotion was suspect, and these don’t appear until the 18th Egyptian dynasty. It’s worth noting that they made their debut in the same small community, Deir el-Medina on the west bank of the Nile, a place that also gave us the first successful labor strike. That, too, is no coincidence. These kinds of intimate songs, seemingly so innocent and inoffensive, symbolized a step forward in personal autonomy and what we would today call human rights. As such, they represented a potential threat to authorities in stratified and hierarchical societies.

And, yes, even a love song can have a coded meaning.

I suspect that the disappearance of most of Sappho’s work was similarly linked to her interest in these lyrics of self-expression—as a result, she was also turned into a comic figure on the stage, mocked the same way ancient dramatists made fun of Orphic mysticism, and a source of scandal in ancient times. In contrast, the poet whose lyrics were most often preserved and cited was Pindar, an establishment figure who sang the praises of powerful men. And if singing about love was threatening to the authorities, how much more dangerous was the Orphic counterculture with its own myths, rituals, ardent believers, and powerful songs?

The most famous line associated with Orpheus is actually a warning that emphasizes this counterculture status: “Close the doors of your ears, ye profane.” We find it in the Derveni papyrus and in other ancient Orphic texts, and it makes clear how little these ritualists craved what we would quaintly today call “crossover success.”

Aloof groups of this sort were sometimes called mystery cults in the ancient world, and almost every one of them was associated, to some degree, with the musician Orpheus. This supposedly mythical figure was real enough, in the view of Greek geographer Pausanias—the closest thing you will find to a sociologist in the ancient world—to be credited as a “founder of mysteries and orgiastic cults of all types.”

The term counterculture, of course, didn’t exist back then, but I note it shares an etymology with the word cult—both linking back to the cultivation of crops with its associations of fertility rites. The cults were both popular as well as mocked and criticized, just as we would expect with a counterculture. Some of them were, as Pausanias notes, involved in scandalous sexual activity, which was in turn connected to concerns about fertility and propagation. But the connection with a counterculture is even more marked in the way the Orpheus ritualists dealt with their music—because songs were even more essential than an orgy to a successful intervention with divine forces.

The Derveni mystic may have wanted to discourage outsiders from listening, but couldn’t help bragging about the power of this music. Again and again, the author wants to have it both ways, much like music critics nowadays. The text shows obvious scorn for outsiders “who do not understand the meaning of things said,” but our mystic can’t help boasting about how much these ignorant people could benefit from knowing the meaning of a potent song.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing here is the insistence that singing the song isn’t enough to help the supplicant who is in a crisis situation. It’s also essential to understand what the lyrics really mean. The Derveni author gets most irate when describing those who turn to other musical ritualists for enlightenment, for “they go away after having performed [the rites] before they have attained knowledge, without even asking further questions.”

So we are left with the surprising fact that not only is the oldest book in Europe about music criticism, but that this is not a trivial detail or mere happenstance. In this time and place, knowing the meaning of a song could be a matter of grave importance (no pun intended). Or even more to the point—the effects of making a wrong choice could last into the afterlife. Was there ever a music fan who made a more extreme claim for a favorite song? Or was more intent on deciphering its hidden meanings? Here we are at the birth of Western culture and we find something very similar to the extreme fandoms of modern times.

Who was this ritualist and others of a similar orientation—and there must have been others, because the Derveni author is so intent on attacking them—who dealt in such arcane practices? I have referred to them as music critics or musicologists, but that clearly only captures a tiny part of their repertoire of skills, which also could include everything from ritual purifications to the interpretation of dreams and omens.

In his recent authoritative survey of the subject, classicist Radcliffe G. Edmonds III is forced to conclude that ancient Orphism had no real scriptures or set doctrines, but stood out instead for its “features of extraordinary strangeness, perversity, or alien nature.” He insists that these practitioners, our first Western musicologists, cannot be called priests or philosophers, but instead are at best freelancers of the spiritual realm—in his words “itinerant religious specialists competing for religious authority among a varying clientele.” In contemporary parlance, we are dealing with gurus and their disciples, a relationship still flourishing in our own times but, just as in ancient Greece, at the margins of society and frequently subject to ridicule, even as eager followers seek out their services.

And what were the occasions that required these gurus and their music? Here the surviving texts provide the most varied and unusual stories. Based on his careful sifting of the evidence, Edmonds concludes that the most likely disciple was the person who lived “life in full crisis mode,” and the rituals themselves were “performed in extraordinary circumstances for extraordinary effects.” In other words, Orphic songs were less like church music, and more like the enabling soundtrack for a hero’s quest.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of this—both for Western culture as well as us as individuals. Before the time of the Derveni practitioner, heroism and immortality were only granted to the gods and rare individuals, such as Achilles or Odysseus, who were renowned for glorious deeds. They were the only ones whose lives were considered worthy of ritualistic celebration. These heroes and gods also had their songs, but these were sung epics such as the Iliad and Odyssey, permeated with the same elitist values. The breakthrough of the Orphic rituals is that they provided a chance at immortality to individuals with less glittering pedigrees—provided that they hired the right musician. Paying clients of lower status were now assured of success in their own journey to the Underworld, and at other moments of crisis and opportunity. But they needed to find the right guru and the proper songs to ensure a successful outcome.

Much of this sounds like mystical baloney to modern ears, too similar to New Age cults that often prey upon the weak and insecure in our own times. Yet, strange to say, the participants in these mystery cults and Orphic rituals of ancient times were often successful, results-oriented people, as the expensive artifacts found in the Derveni necropolis make clear. Even so, this didn’t insulate them from attacks and derision. In fact, the biggest obstacle we face in understanding these old songs and their rituals comes from the intense mockery and criticism of respected authorities—Plato, Aristophanes, and other esteemed sources of antiquity. Nor did this backlash end in later times. Attacks on Orphic practices continued unabated in the Christian era, and this tradition of skepticism and dismissal has persisted in the academic discussions of modern times.

Why has this magical, ritualistic music inspired so much loathing and hostility? As I’ve written elsewhere, the Derveni manuscript originated during the most powerful—and poorly understood—rupture in the history of music. Under the influence of Pythagoras and his followers, music was getting turned into a kind of mathematics. Precise tuning systems and defined scales were creating a new approach to song that would dominate and define Western music until quite recently. In contrast to that algorithmic imperative, the magical and miraculous aspects of music—so essential to its origins and purposes—were increasingly viewed as an embarrassment, superstitious babbling that shouldn’t be taken seriously and, if possible, eradicated completely. That attitude is such a core part of modern musicology that it isn’t even discussed nowadays. Any music scholar who decided to treat songs as a type of sorcery would turn into the laughingstock of the profession. Are we surprised then that no professor has stepped forward to embrace the Derveni papyrus as a guide to the origins of musicology?

Before closing this chapter, I need to highlight one more aspect of this marginalized and erased tradition—perhaps the most embarrassing of them all for a sober modern scholar. As we have seen the Derveni author was also interested in coded meanings—that subtle signifying described by Henry Louis Gates. But the question remains: Where did our Derveni ritualist musician learn to interpret these meanings?

This isn’t a hard question to answer, but answering it adds to our shame. Ancient ritualists knew how to interpret dark, deep meanings because they did it professionally—cutting into animals and predicting the future after examining their entrails, or going into ecstatic trance states and asking questions of a totem animal or higher power, or interpreting an oracle from the gods, or soothsaying on the basis of dreams and uncanny events.

In other words, music criticism was not just practiced by magicians but actually originated as a kind of sorcery itself. Believe it or not, divination is the source of all of the current-day variants of what we call criticism or textual interpretation or (to apply a fancier label) hermeneutics. In the beginning, it was all a kind of wizardry. Soothsaying and magic somehow evolved into album reviews in Rolling Stone or scholarly musicology papers sent out for peer review.

A similar evolution took place in what we call highbrow culture. As it evolved, so have the codes, but once you learn to recognize them, you find them everywhere. They, too, have been assigned fancier names. Instead of secret or code, we call them allegory, metaphor, anagoge, simile, and parable, among other things. But the structure is the same. Meaning operates underneath the surface, and the interpreter must journey below the superficial level to find the real significations at play in the nether realm. But they are all variations on the augur’s craft, not much different from the 150 ciphers of the Irish bards, or the “Solaristic Precepts” of Sun Ra and John Coltrane, or the esoteric knowledge of the Derveni ritualist.

Before proceeding to chapter two (where we start to understand the practical implications of all this), let me summarize the odd and perhaps unsettling things we’ve learned so far:

(1) Musicology originated as sorcery and divination.

(2) Songs were widely recognized as repositories of remarkable powers—although this view was later discredited and, in most spheres of musical life, eventually forgotten.

(3) Important songs contain secret information, and the most powerful practitioners not only could perform the music, but also understood the hidden meanings. They were, in a very real sense, code-breakers.

(4) Music is useful in decisive or dangerous situations, and at the most important interludes in human life—hence musicology must address this reality. At the birth of Western culture, the most esteemed musician, Orpheus, was also celebrated as chief protagonist in the most dangerous and ambitious hero’s quest known to ancients: the journey to the Underworld to bring back a dead soul through the power of music. As such, Orpheus was a role model for others who sought musical interventions in moments of crisis and uncertainty—both in this world and elsewhere.

(5) Music is the engine that empowers the hero’s quest. Those who hoped to surmount these obstacles in a transformative, decisive process —what I call here the genuine hero’s journey—need the right songs to make it happen.

(6) Everybody can participate in this. The musical intervention embedded in the Derveni papyrus made a kind of heroism and immortality, previously attainable only by deities and rare individuals, accessible to anyone brave or daring enough to pursue the quest. These heroes were the forerunners of today’s musicians, and they not only sang their amazing songs but defied authorities by advancing human rights and expanding personal autonomy.

Did you ever imagine that music could do all that? But we’ve just begun our journey.

TO READ CHAPTER TWO, CLICK HERE.

Footnotes:

momentous things in riddles: Gábor Betegh, The Derveni Papyrus: Cosmology, Theology and Interpretation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 17. For ‘signifying’ and the trickster tradition as a theme in African American culture, see Henry Louis Gates, The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

founder of mysteries and orgiastic cults of all types: W.K.C. Guthrie, Orpheus and Greek Religion: A Study of the Orphic Movement (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), p. 126.

who do not understand the meaning: Gábor Betegh, The Derveni Papyrus: Cosmology, Theology and Interpretation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 15, 17, 19.

without even asking further questions: Gábor Betegh, The Derveni Papyrus: Cosmology, Theology and Interpretation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 43.

features of extraordinary strangeness: Radcliffe G. Edmonds III, Redefining Ancient Orphism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 71.

itinerant religious specialists: Radcliffe G. Edmonds III, Redefining Ancient Orphism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 8-9

life in full crisis mode: Radcliffe G. Edmonds III, Redefining Ancient Orphism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 247.

rupture in the history of music: For Pythagoras as initiator of the key rupture in Western music, see Ted Gioia, Music: A Subversive History (New York: Basic Books, 2019), pp. 48-56, and Ted Gioia, Healing Songs (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2006), pp. 89-108.

"In contrast to that algorithmic imperative, the magical and miraculous aspects of music—so essential to its origins and purposes—were increasingly viewed as an embarrassment, superstitious babbling that shouldn’t be taken seriously and, if possible, eradicated completely."

This (and the discussion of Sun Ra) reminded me of the following passage from Bob Dylan's "Chronicles, Volume 1":

"Prior to this, things had changed and not in an abstract way. A few month earlier. something out of the ordinary had occurred, and I became aware of a certain set of dynamic principles by which my performances could be transformed. By combining certain elements of technique which ignite each other I could shift the levels of perception, time-frame structures and systems of rhythm which would give ny songs a brighter countenance, call them up from the grave -- stretch out the stiffnesss in their bodies and straighten them out. It was like parts of my psyche were being communicated by angels..."

I feel you do a disservice to Pythagoras, who very much had his own mystery cult (but also had the math to back his suppositions), in your effort to promote the Orphics. Having watched your interview with Rick Beato where you stated the thesis for this book, I acknowledge you want to discuss the marathon-like nature of ritual and "primitive" trance and devotional music. But as an academic who spent a tremendous amount of time researching Robert Graves and Idries Shah and Omar Ali Shah, I found that authors who typically delve into The Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth are going for the full Dan Brown-Robert Blyth esoteric pop lit that sells enough to become hipster tavern conversation. Rarely, among all the esotericism, is the answer given to the question you posited: "why are the mystics, musicians, and poets killed and forgotten?" The answer is "mistakenly speaking supposed truth to power." Whether BraveHeart or John the Baptist or any of the folks you've named, "hocus-pocus" is psychological, real politic- real power- is physical. Salome can in fact have John's head on a plate, no matter how powerful John's magic faith might be. The Hasmoneans win again! Christ annoys the Temple leadership and is flippant to Pilate, and gee whiz, gets nailed to a tree. Rome wins again. The Celtic Bards traveled around to patrons telling them to their faces in front of an audience the actions it had taken to put -and keep- those leaders in power. Cubano son or US rap, say what you can get away with until shot dead in the calle. There are plenty of pagans in Austin, who maintain places of worship and meeting houses, some who supposedly still practice Orphic Rites. I'm sure they will let you sit in a damp field on shrooms, listening to drone music from mediocre "musicians." But the fact that all of that trippy, heavy, meaningful sound is created for spiritual, divine-seeming reasons in no way makes the field less damp and soggy.... And the converse to the esoteric jive, is Bach or Bill Evans or Barry Harris or Jim Hall who had a sign that said "Make Musical Sense" in his guitar case. Thanks so much, Pythagoras!!