Why I Ran Away from Philosophy Because of Sam Bankman-Fried

Or how flawed thinking can make $10 billion disappear

I abandoned philosophy because of Sam Bankman-Fried, the crypto scammer.

Well, that’s not entirely true. I abandoned my formal study of philosophy because of people like Bankman-Fried.

Unfortunately, they were my professors at the time.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Where do I even begin in telling this?

It’s not easy. That’s why I’ve never given a full account of my years as a philosophy student at Oxford—despite some readers requesting this. I don’t talk about it because the story is complicated.

But Sam Bankman-Fried gives me the excuse—or even the necessity—of digging into this gnarly matter. That’s because the crypto scammer was deeply involved in a philosophical movement that originated at Oxford. It draws on the same tenets I was taught in those distant days.

My teachers didn’t run crypto exchanges, and (to my knowledge) never embezzled anything more valuable than a bottle of port from the common room. Even so, there’s a direct connection between them and Mr. Bankman-Fried.

They were erudite and devoted teachers, but I was disillusioned by what they taught. It eventually chased me away from philosophy, specifically analytic philosophy of the Anglo-American variety.

I had no idea that their worldview would come back to life as a popular movement promoted by the biggest scam artist of the digital age. But I’m not really surprised—because it’s a dangerous worldview with potential to do damage on the largest scale.

The philosophy is nowadays called Effective Altruism. It even has a web site with recruiting videos—there’s a warning sign right there!—where it brags about its origins at Oxford.

But here’s the catch, if you actually try to put this philosophy into practice, you might sell your granny to sex traffickers.

You think I’m joking?

In fact, that’s exactly what you would do. Effective altruists don’t look at the actual actions at hand or their consequences today—hah, that would be too obvious. They only think about long-term holistic results, and hope to maximize pleasure and good feelings in the aggregate:

So it stands to reason that:

Granny is old and doesn’t have long to live, so she can’t experience much pleasure even under the best circumstances.

But the sex traffickers could use Granny to increase the pleasure of many of their customers.

Hence….

I’m not going to spell it out for you, but you can guess where this is heading.

You just better hope that, if you’re ever a grandparent, your progeny aren’t Effective Altruists.

This may sound like a gross parody of a philosophical system. But variants of this way of thinking are everywhere in Anglo-American philosophy, inherited from Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, and other utilitarians. They were the geniuses who decided that morality must aim at maximizing pleasure.

That doesn’t feel right, does it?

Maximizing pleasure leads to vice, not virtue, doesn’t it? Didn’t Harvey Weinstein aim to maximize pleasure? And Charlie Sheen and Bill Cosby and all the rest?

It’s obvious that these vagabonds and criminals shouldn’t be role models in virtue. But it’s only obvious for you and me—not among utilitarians or in Sam Bankman-Fried’s circles.

You can use this philosophy to justify almost any terrible act.

You merely need to point to the larger context. Embezzling billions of dollars is only a start. Just consider the current social media justifications of atrocities in the Middle East.

These hatemongers explain that it may seem wrong to murder babies or rape or kill innocent people, but you only need to understand the larger context, and it’s all okay.

Whenever you hear this vague reference to the larger context, you better start running.

The proponents always talk about the distant past or the distant future—to defend something horrible happening today and right in front of your eyes. They’re looking out so far in the distance, they don’t even see the blood or corpses.

That larger context is a trademark of Effective Altruism. And it’s another huge warning sign.

Ends not only justify the means nowadays, but obliterate them. Sam Bankman-Fried is the poster child for this worldview, and we need to learn from his crimes. But there are millions of otherwise smart people buying into this.

So even if Bankman-Fried goes to prison for a hundred years, granny is still very much in danger.

Before proceeding, here’s a quick story:

My friend M— came to Oxford to pursue a graduate degree in philosophy. The first week at Oxford, M— met with the esteemed philosopher Lord Q—.

Lord Q—: “We are so glad to have you here at the college. Now tell me, have you studied philosophy before?

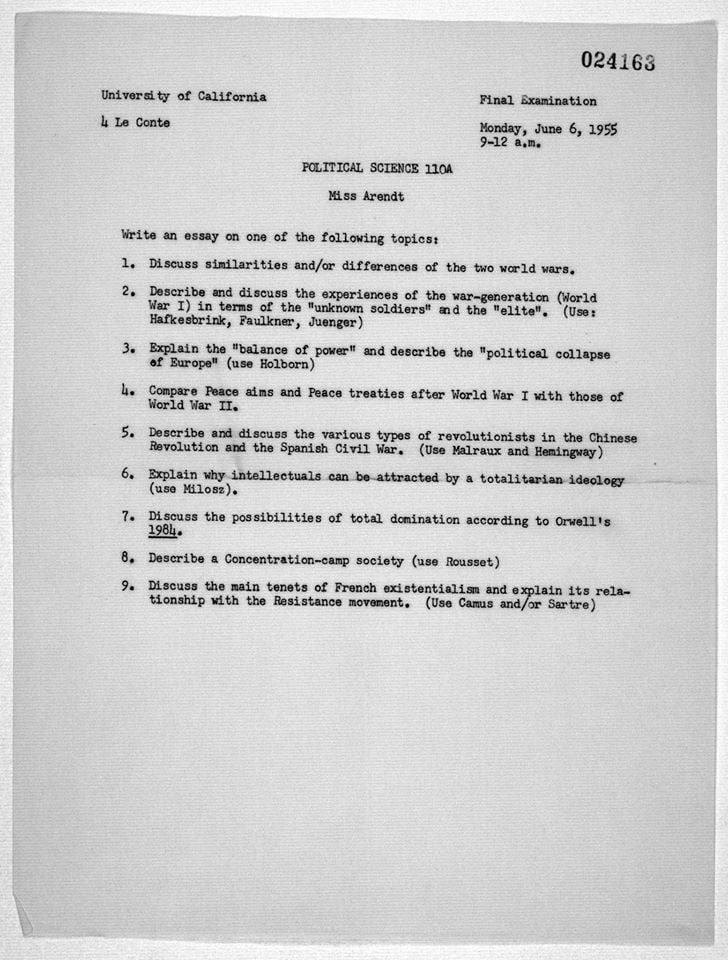

M—: “I did my senior thesis on Hannah Arendt.”

Lord Q—: “Hmm, Hannah Arendt?”

M—: “I focused on her books on the abuses of power, especially The Human Condition, On Violence, and The Origins of Totalitarianism. I examined….”

Lord Q—: Hmm. Yes, Hannah Arendt. Hmmm….But have you ever studied philosophy?”

I really must emphasize the many positives of my philosophy studies. I enjoyed living in Oxford—those were very happy years. I liked my classmates and teachers. I benefited from the emphasis on rigorous logic, critical thinking, and scrutinizing propositions rather than taking things at face value.

I still write and think better today because of the discipline imposed on me during this period. I also gained a lot of poise and confidence along the way.

I was good at this game. I was awarded a first in my degree—beating out a dozen Rhodes Scholars who took seconds that year. I could have pursued a career as a philosopher and made a living at it (no small feat that).

But I never considered doing this. I actually grew more committed to my jazz music during those years—less A.J. Ayer, and more J.J. Johnson! It felt like an escape from the claustrophobia of all those reductionist linguistic and consequentialist philosophies.

I was dismayed by many of the things I was taught. Actually, it’s even worse than that—I was alarmed by the larger framework in which these theories were promulgated. It imposed a practicum that took anything vital and life-giving, and turned it into a patient etherized on a table.

So I left philosophy behind with no regrets. Actually I experienced some relief when I started playing more jazz gigs—because a flawed worldview can do more harm than a bomb or a gun, and is much harder to disarm.

By the way, it’s ironic that Sam Bankman-Fried is going to prison. That’s because the key progenitor of his consequentialist ethics, a curious man named Jeremy Bentham, actually invented a prison (and did other creepy things).

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

All this not only explains the ambitious scope of Sam Bankman-Fried’s crimes—you should expect nothing less from an Effective Altruist. They always dream big. But it also helps us understand why SBF refused to plead guilty, and shamelessly defended his actions despite the huge damages incurred.

He still was pointing to that larger context.

The real scary stuff here is all the fanboys, like Michael Lewis and the codependents at the New York Times and elsewhere, who continue to buy this hokum, even now. They are far more dangerous than a pathological crypto scammer.

Just discussing this gets some people very upset. They don’t like it when you judge a philosophical system by the activities of its practitioners. They say it’s unfair—a brilliant thinker might lead a totally disgusting and dysfunctional life but, they claim, this has zero relevance to the theories espoused.

There’s another warning sign for you.

It’s true, of course, that a philosophical system is not disproved if its advocates are criminals and tyrants—but this linkage must be a cause for alarm and suspicion. The burden of proof is on those who want to separate a person’s core principles from the results they produce in actual life.

I was already grappling with this problem as a grad student. I hoped that studying philosophy would lead me to the good life—a way of existing that would develop my human capacities, make me a better person, and contribute in some way to making life better for both me and those around me.

The mistake I made was bringing those expectations to Oxford. Maybe in France or Italy or Germany, I could have attended a university in search of the good life. But the Oxford analytic tradition was all about words, not living.

It was linguistics meets necrophilia. Meanings were dissected like frogs in a high school biology class—and with the same result. All vitality and meaning was drained out of them. You could almost smell the formaldehyde.

They even bragged about how they killed meanings—spouting off things like “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” That should have been another warning sign. The more deeply they dug into linguistic explanations the more vague and inconclusive were the findings.

This is heavy stuff, so it’s time for a joke.

This comes from a 1960s comedy skit about Oxford philosophy, later popularized by John Cleese and Jonathan Miller.

John Cleese: “Yes.” [Pause] “Yes. . . yes.”

Jonathan Miller: “Tell me—are you using yes here in the affirmative sense?

John Cleese: [Thinking carefully and scratching his head—finally responding after a long pause]: “Nooooo.”

If you’ve sat through an Oxford philosophy tutorial, that hits close to home.

In this environment, right and wrong—very simple notions that everybody understands, even tiny children—become deeply problematic. When confronted by these concepts, the Oxfordian response is either to ignore them, dismiss them, or analyze the meaning of the words.

Sam Bankman-Fried tried something like that on the witness stand. It might work in an Oxford tutorial, but the jury was not convinced. It only took three hours to deliver a verdict: Guilty on all charges.

Time for a second joke:

The story is told of an Oxford don who was scheduled to lecture on the meaning of life. A large audience gathered in anxiety to hear the opening lecture.

They were relieved when they found out that the philosopher only wanted to discuss the meaning of the word ‘life’.

I eventually discovered that there were much smarter moral systems—and ones that were safer for Granny. These might involve Kant’s categorical imperative or Aristotle’s virtue ethics or the natural law espoused by Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King or even the Ten Commandments.

But neither Kant nor Aristotle were British. And the same went for Moses and Gandhi and Dr. King.

So they didn’t get much respect in the Oxford Senior Common Room. Instead we got consequentialist ethics of various homegrown denominations. Sam Bankman-Fried’s Effective Altruism is just the latest rebranding.

And even if Sam Bankman-Fried goes to prison for a hundred years, Granny still needs to worry. That’s because plenty of others share this worldview.

One last story—which sounds like a joke, but isn’t.

A close friend of mine was having personal problems at Oxford so she went to a philosopher for advice.

That may strike you as strange. Don’t people go to counselors or therapists for guidance? Who would dare ask a philosopher?

But she did just that, and she chose one of the greatest living thinkers, Charles Taylor—although Taylor was hardly as well known back then as he is now. (Things have changed. In more recent years, Taylor has won two separate million dollar philosophy prizes!—see here and here.)

After talking to Taylor, she would tell me what he said. His advice was moving and insightful, focusing on the extraordinary power of love, compassion, and forgiveness in our lives.

But here’s the key point. I had heard Taylor give public lectures at Oxford, but what he said from the podium was very reserved and analytical. He was actually making far more profound statements in a private conversation than he did in his public role as an Oxford philosopher.

That was very revealing to me. What does it say about an education system that forces its best teachers to hold on to their deepest wisdom as a kind of secret lore for private consumption?

By the way, Taylor eventually dealt with many of these issues in his philosophical writings, but that only happened after he left Oxford. If you’re looking for genuine insight into the human condition, you should read his later works, and give a pass to Sam Bankman-Fried and Effective Altruism.

I’ve griped a lot above, but I still prize my time at Oxford. Every day of my life, I rely on what I learned there.

The only twist is that my most important discoveries were due to what I learned to avoid in my own thinking and doing.

But I could have never understood these things unless I had spent so much time deeply immersed in this philosophical tradition. If I had gone to the Sorbonne or a Zen monastery instead, I would have found a more congenial worldview, but I would have missed out on the cautionary lessons that only Oxford can teach.

This deserves an essay of its own. But I will skip that here, and merely provide some alternatives to the errors I confronted as a philosophy student.

Here is what I believe today:

Words are something you live by. They are defined by your actions, not by other words.

We rely too much on numerical measures and reducing things to formulas—the most valuable things in human life resist quantification.

I’m referring to core human values—such as love, compassion, forgiveness, trust, kindness, fidelity, decency, hope, etc. These are practices not arguments, and hence require no appeal to a larger context. Anyone who claims they require arguments (for falling in love or acting compassionately, for example) should be treated with extreme caution.

Above all, beware of people who won’t do a good deed until they have calculated the long-term consequences and expect certain desired results in return. Maybe you can do a business deal with them (or maybe not), but never get into a close personal relationship with them.

Gratuitous actions of generosity and kindness are best done without calculating rewards or consequences (which, by the way, is the reason I’ve celebrated gift giving and the bonds of trust and love it creates in my writings).

Some choices are intrinsically evil. No larger context can cleanse them of this evil.

Practicing good must begin in the immediate context of your life—in your actual actions today, not in some mythical past or dreamt-of future. And finally….

Take care of Granny.

I reached those conclusions before Sam Bankman-Fried was even born. Curiously enough we both studied the same philosophical tradition in formulating our worldviews—the only difference is that I ran away from it, while he put it into practice.

I could say that I feel vindicated by this recent turn of events. But vindication is irrelevant here. A life of love, kindness, friendship, etc. provides its own rewards. We shouldn’t need a cautionary tale about a $10 billion scam to grasp that.

But for those still in doubt, there’s now a case study to clear up any confusion. I wonder if they will teach it at Oxford.

You’re one of my very favorite writers, and I feel like I learn a lot from your column. I don’t know how you’re able to read so much, listen to so much, and write so much; your productivity is astounding, and you do it all with unique insights.

Today’s column is the first time I’ve felt you were unfair, and not just a little.

My son works for an Effective Altruist (EA) organization founded by a multi-billionaire to research how he can spend his billions of charitable dollars to do the most good. My son lives and breathes EA, and I have never heard him talk—not once--about "maximizing pleasure." He’s currently in Ethiopia leading a delegation of South Korean parliamentarians, showing them vaccination facilities and other cost-effective ways to save lives in a country that needs support; the hope is that the parliamentarians will lobby their government to increase funding for such projects. EAs tend to focus on countries where the most good can be done at the least cost, so developing countries are at the top of their list.

It’s true that many EAs are consequentialists, but not in the name of having a good time. They deal with dicey equations like how much sacrifice today is justifiable to achieve a better tomorrow. Similarly, they’ll make the difficult suggestion that resources spent to do good on the local level in this country would be better spent in another country where the dollars—and the good that can be done—go much further. That part of EA can make a lot of people uncomfortable, and understandably so, but that doesn’t make it wrong.

Aspiring EAs have traditionally had two primary career choices: working within EA to identify and promote charitable causes that give the most bang for the buck (i.e., lives saved or substantially improved per dollar spent), or “earning to give”—following the path that maximizes the amount of money they can make and thereby eventually donate. Samuel Bankman-Fried gave the EA movement a big black eye by twisting “earn to give” to allow ripping off investors and shareholders. Effective Altruists would not support any such unethical activities, and they’ve dialed down the whole “earn to give” side of the equation as a result of what he’s done. Samuel Bankman-Fried may have started as—or claimed to be—an Effective Altruist, but in no way does he represent the movement. The day his criminal activities were revealed was absolutely brutal for Effective Altruists; not only did he damage the movement in the public eye, but billions of dollars that were expected to go to charitable good vanished. To be very clear: The EA movement would have endorsed his plan to make as much money as possible to donate to worthy causes (if he ever really meant that), but they would never have endorsed the way he went about it. He can call himself an Effective Altruist, but I challenge you to find an Effective Altruist who would want anything to do with him.

I’m curious where you came up with the idea that Effective Altruism is about maximizing pleasure. Is it in writing somewhere? If not, I think you’re being grossly unfair, and I honestly don’t understand why; it doesn’t seem at all consistent with all the well-researched and unerringly fair columns you’ve posted in the past. The whole device about EAs supporting the idea of Granny being sold to sex traffickers to maximize human pleasure in the long run seems—and I hate to say this to someone as deep and thoughtful as you—completely disingenuous and terribly misleading. I challenge you to find a single Effective Altruist who would support it.

And, yes, my progeny is an Effective Altruist, and I’m very proud of him. He lives his life to achieve the most benefit for mankind (and animals as well—animal welfare is a major EA concern); he puts me to shame. "Maximizing pleasure" is part of the equation only insofar as it makes him feel good to have a positive influence on the world.

My son is based in the Bay Area, and I would love for you to get to know him to see what kind of “hate monger” he is. I’m sure he’d welcome the opportunity to talk with you about it.

First: I am a HUGE fan. Second: this is the one and only time I’ve read something of yours and thought, “this is a terrible piece of writing.” Just to be clear, I’m not saying that because I think your conclusion is faulty. In fact, I have no idea whether you’re right or wrong because I have no training in philosophy, aside from a political theory class I took when I got my JD at Berkeley.

What I am saying is that, as a piece of analysis/persuasion, this is a failure. You start by making some very strong claims about “Ethical Altruism,” e.g., it could make you sell your granny to sex traffickers. But you never walk the reader through specific tenets of the philosophy and how they’ve been applied to do terrible things in the world. You make a remarkably general proposition about EA, then you blame it for a litany of horrible behavior.

Where is the causation analysis? Many people go to law school (or business school) and later do terrible things. Did they do them because they went to law school? Maybe, maybe not. I’m completely open to the possibility that EA is a force for awful behavior in the mold of Sam Bankman-Fried. But your piece does absolutely nothing to persuade me that EA is, in fact, the cause. It’s entirely possible that an advocate could argue (maybe fairly, maybe not), that what Bankman-Fried did was a perversion of the philosophy, not an application of it, in the same way some people pervert religion for terrible ends.

Bottom line, this feels more like a personal vendetta than an argument, and for me, that’s a serious disappointment coming from you, because you are normally so careful and methodical in the way your marshal facts and arguments.