Why Do Children Hate Music Lessons?

I love music, but not how it’s taught

Few things in life are more fun than making music. It’s just the lessons that suck.

That’s according to children—who are rarely consulted on such matters. But their actions speak louder than words. Most of them give up music-making forever after a short exposure to lessons.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

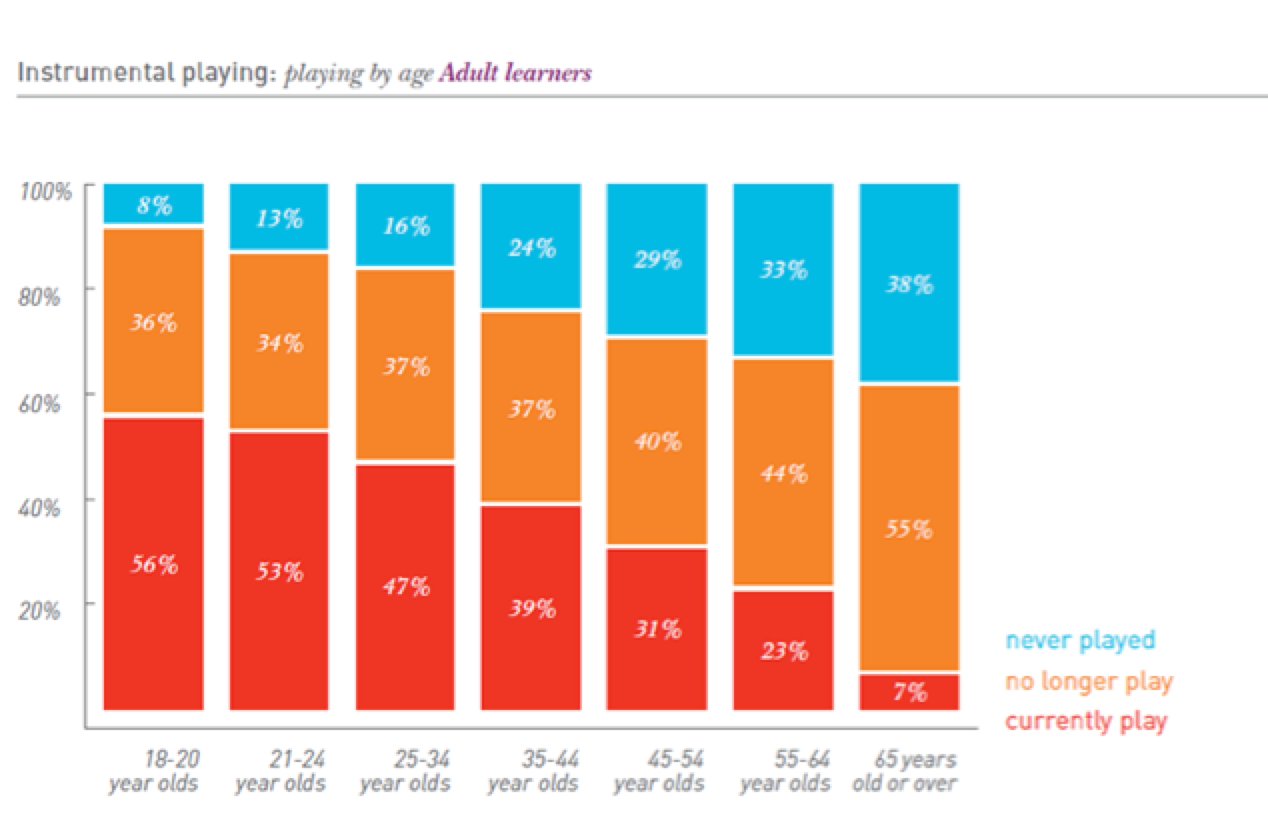

These figures are from the UK, but I suspect the trend is similar elsewhere:

If music is so much fun, why are music lessons so painful?

I’ve often pointed out that only three careers turn work into play. Even our choice of words reveals that. An athlete plays a sport. An actor plays a role. And a musician plays an instrument.

Everybody else goes to work.

Anyone who has the privilege to pursue one of those three careers is truly blessed. You can complain as much as you want, but the rest of us see that your job is just play.

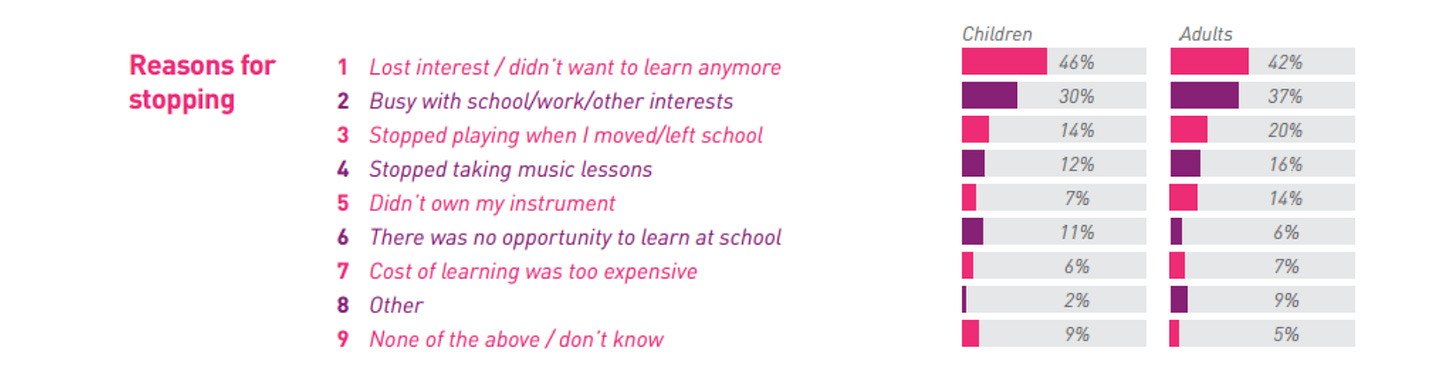

The reason most people abandon music lessons isn’t cost or time—they just don’t want to keep doing it. It doesn’t feel like play to them.

The shift from elementary school to high school is the typical time when youngsters abandon music.

This is puzzling for many reasons. For example, I found that I only started gaining social esteem and other benefits from my music-making around the time I turned sixteen. And that’s when most teens stop learning music.

I hadn’t expected that all those hours at the piano would give me a popularity boost—that wasn’t why I studied music. And it surprised me when I started experiencing it, but I certainly didn’t complain. Maybe playing the piano wasn’t quite as cool as being captain of the football team, but it turned out to be pretty cool nonetheless, especially if you knew how to play some of the hit songs on the radio.

The funny thing is that I’d experienced piano lesson burnout—but that happened back when I was nine years old. I hated my piano lessons, and asked my parents if I could stop taking them. They agreed, and so my musical education came to a grinding halt after 4th grade.

But here’s the interesting thing. I continued to play the piano after I stopped taking lessons—but now I did it for fun.

I made up my own songs. I learned other songs I liked by ear. I actually played the instrument more after those awful lessons had been terminated.

Years later, I took a few more lessons—I had a teacher for several months around the time I was thirteen, but now it was my decision, not my parents. I also took lessons from other teachers during my senior year in high school and the first term of my freshman year in college.

And that is the sum total of my formal music education at the piano.

Finally, when I started playing jazz professionally in my twenties, I wondered whether I should find a real jazz teacher. But by that time, I was fairly advanced in my playing, and needed a real hotshot professional to guide me, and there were only around a half dozen pianists in Northern California I really trusted in that regard. I made an unsuccessful attempt to enlist the late Jessica Williams as a teacher. But it didn’t work out—because… well, let’s say she made some unusual demands.

So I developed without jazz teachers, both as a musician and as a music historian. There’s some irony in that. I had access to amazing professors at illustrious universities, but jazz wasn’t part of the curriculum. In the field in which I made my reputation, I had to teach myself.

I’m not especially proud of that. Too much of what I’ve done in life has happened outside official channels. I’ve missed things by not accessing the right teachers at the right time. Things I did learn, I might have learned faster with proper guidance.

On the other hand, you learn very deeply when forced to invent your own pedagogy. And I take some comfort in knowing that there were almost no jazz teachers for the generations that came before me. Many of the jazz pioneers learned by doing—and they turned out okay.

In any event, my particular life story makes me a good judge of why youngsters stop studying music—and also of what circumstances might allow them to continue in a satisfying way.

So here are my observations on why children hate music lessons. In part two of this article, I will explain how I’d change things if I were a music educator.

(1) The first problem is that they’re called lessons. Music-making is fun, but music lessons are something very different. The first change I’d make is eliminating the word lesson from my vocabulary. I’d get rid of the word practicing too.

And fortunately we already have a better word—it’s called playing. You play your instrument, and the experience is one of fun and playfulness.

(2) Music carries the heavy baggage of the entire education bureaucracy, and this makes everything boring and burdensome. As Paul Graham has rightly pointed out, the single biggest impact of early education is to convince students that hard work is pointless and should be avoided at all costs. Too much of homework and testing is designed solely for the purpose of convincing a teacher of your competency. The idea that you might work hard for your own benefit is never taught in school, and many people never realize that important fact.

Music lessons suffer because they rely on similar metrics, and are often integrated into our bureaucratic educational system. So even something intrinsically fun (like music-making) starts to feel burdensome.

(3) Parents are part of the problem—maybe the biggest part. Suzuki, the great music education innovator, realized this early on. He found that parents imposed all sorts of negative attitudes on to their children. They yelled at them to practice more. They sat in judgment at recitals. They had vague ambitions about how their children’s performances would enhance their own status. Etc.

In fact, the history of music lessons shows that this has always been the case—the rise of piano ownership has always been associated with class aspirations. And the most frequent reason these lessons got embraced by families during the 18th and 19th centuries was to improve the marriage prospects of their children.

Things have changed a little since then, but we still have non-musical motivations for imposing these lessons on youngsters. These only increase the drudgery of formal music education.

(4) The endless round of recitals, auditions, and competitions create a perfection-driven culture that diminishes—and often kills—the sheer joy of music-making. Ethnomusicologists have studied many societies where everybody participates joyously in music-making—but that only happens when you don’t have auditions and competitions to weed out poor performers. If the goal is to enhance your inner joy and satisfaction, you would do things very differently.

When my youngest son was a teenager, he was fortunate enough to play in a school orchestra that frequently won the state competition. But, as it turned out, this wasn’t as fortunate as it seemed. I feared that the unrelenting focus on competition would destroy his love of music.

I saw it happening. He was advancing in proficiency, but losing his joy in the process. So when he discussed quitting orchestra, I not only supported that decision but encouraged it—in the face of all the experts who told us this was a mistake.

(In the follow-up article, I will tell you what he did instead—today we’re dealing with problems, not solutions—but the end result is that today he is an excellent musician who enjoys every aspect of his craft.)

(5) The ultra-intense hype on music lessons as building blocks of high educational achievement just aggravates the situation. Sure, I believe all the hype about the links between music-making and improved academic performance. Music probably does activate and nurture the same part of the brain you use for math and science. You probably do get better grades if you’re a focused, dedicated musician. But this kind of attitude treats the music itself as a negligible byproduct, instead of celebrating the intrinsic joy of music-making.

If you learn music for this reason, you will never get the greatest benefits from it, which can’t be reduced to a GPA or SAT metric.

(6) The Western classical music tradition is amazing, and I cherish it every day of my life, but an educational system that just focuses exclusively on scrupulously playing note-for-note compositions written by people who died long ago is a mistake. If you want to convince people that music is stagnant, you couldn’t find a better method. Let’s keep Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and all the rest—I love them dearly; but let’s also embed them into a larger practice that is alive and vibrant.

Those are the problems. And they’re big ones. In my follow-up article, I’ll suggest ways of dealing with them. But be forewarned: My approach to music education will be radically different from the status quo.

Counterpoint 1: If you don’t learn any technique or practice discipline, it is much harder to come back to it later when you want to.

Counterpoint 2: I’ve met tons of adults who regretted quitting music lessons in their childhood. I still haven’t met one who took lessons all the way through high school and wished they had quit. (I suppose you are all going to come out of the woodwork now.)

I realized early on that I needed to balance leaning into learning newer and more challenging musical tasks with having musical fun. And fortunately (it turns out now, though it didn't feel that fortunate at the time, since it often got me into trouble) I had a penchant for playing my own thing a lot of the time when I was supposed to be practicing something else. Fun is the fuel that makes any long musical journey possible. When I taught music, I always tried to make sure my students were spending at least as much time working on things they felt were fun as things they might not have had much fun with.

I always tried to tie the less fun tasks to specific goals the students had rather than the idea of practice for practice's sake. Like you were saying, things seem to go better for students when they're they ones who want to practice. If they don't learn to drive their own development engine, they're going to quit anyway, so you might as well teach them to pilot the ship.