Why Did Medieval Cities Hire Street Musicians as First Responders?

Musicians patrolled streets and city gates—they carried badges and even took an oath of office. But why?

You can tell a lot about a city just by counting up its essential workers, all those police officers and fire fighters and other specialized personnel it keeps on the payroll. But six hundred years ago, cities hired lots of street musicians—and it happened all over Europe. Any sizable municipal government recognized the need for musicians as part of what we today call first responders.

Consider the peculiar law in London in the late medieval period, that required each entry gate into the city to keep a musician on duty. This could be a dangerous job—city gates were where attackers and other threatening outsiders first appeared. It’s like border patrol nowadays, but they gave the job to musicians.

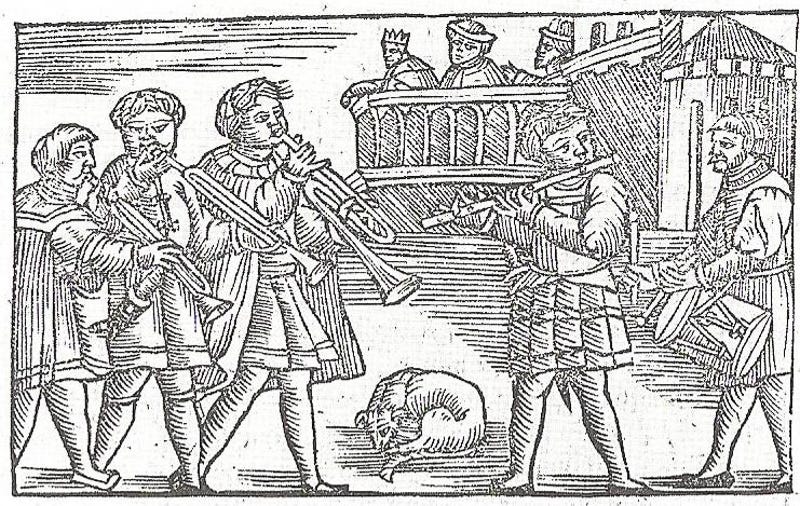

In Germany, a minstrel was expected “to acquit himself well as a swordsman.” Surviving illustrations tend to emphasize the bulky, formidable aspect of these street performers. But why?

As strange as it sounds, musicians took charge of many essential services back then. These hired municipal minstrels started showing up everywhere in Europe around the year 1370. In Italy they were called piffari, in Germany they were known as stadtpfeifer, in Holland they were stadspijpers, and in England they were known as waits. They typically played wind instruments—including trumpets, trombones, fifes, bagpipes, and recorders—as well as percussion and sometimes viols.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

To the modern mind, musical skills and police responsibilities have little in common, but in an earlier age the two roles often overlapped. Musicians not only helped defend the city gate, but might also be required to patrol streets at night. In Norwich in 1440 a tax was instituted to pay the waits for their watch—and these musicians were required to take an oath of office. In Germany, a minstrel was expected “to acquit himself well as a swordsman.” Surviving illustrations tend to emphasize the bulky, formidable aspect of these street performers.

But why?

The most obvious answer is that musicians were ideal first responders because they could sound the alarm in case of a major disturbance. Certainly a loud horn or drum helps in that regard. (I’m less confident in the fife and viol—but I guess you take what you can get.) This signaling capacity of musical instruments also explains their longstanding use in military operations.

But this explanation doesn’t capture the much deeper reasons why cities needed musicians on the payroll. If you study the surviving documents—hard to find, and mostly ignored—you will see that guarding gates and streets was only a small part of their responsibilities. In fact, these medieval musicians were at the center of all important events. You might even say that civic pride was centered on these performers.

They are sadly written out of the historical accounts. In J.R. Green’s book Town Life in the Fifteenth Century, for example, these musicians are ignored except for a single sentence. But even that one sentence is more than what you will find in many books on medieval society—including music history books, which seem to operate on the principle that only music notated and preserved in archives deserves our attention.

Towns even had their special music and their own tune—a kind of theme song, much like TV shows and consumer brands nowadays. No self-respecting city would operate without its own distinctive soundtrack. It’s a fascinating subject, rich with psychological implication, but who has written its history or probed its meaning?

Above all, the street musicians gave the city a sense of pomp and ceremony—turning the everyday into something special. Municipalities placed them at the city gate not just to make a loud noise during an attack but also to greet noble visitors with suitable music. The historical records make frequent reference to these practices—for example, Henry V’s entry into London from the battle of Agincourt in 1415 was heralded at the gateway of London Bridge with horns. There was even an “Agincourt song” which fired up the crowd. In 1378, when the Holy Roman Emperor met with King Charles V in Paris, the monarch greeted his formidable visitor at the outskirts of the city with trumpeters playing silver instruments, and minstrels stood at the very front of the royal retinue. Again and again, surviving documents tell us that musicians were given a place of honor at such historic junctures, where they served as a focal point for all ritual and revelry.

For the same reason, cities often required their musicians to play from the top of the bell tower because that was the emotional center of the town. It’s revealing how often huge battles in medieval wars were fought to take control of a bell tower. You couldn’t claim a genuine victory until you owned that symbolic spot—the command center for the soundscape of the city below.

Even where I live—a city that brags that it is the “live music capital of the world”—musicians are still freelancers, not permanent employees. . . . I certainly appreciate those clubs and their commitment to live entertainment. Even so, I’d love to see horn players at the Austin city limits.

That same obsession with civic pride explains why musicians had to dress in the most splendid costumes. A painting by Gentile Bellini, Procession from 1496, shows the piffari in ceremonial attire, and other surviving works of art convey the lavish care devoted to the appearance of these civic performers. For example, all of the musicians at the 1409 Lord Mayor’s Procession in London were dressed in red and white hoods that earned high praise from onlookers. The records from many cities indicate the payment of funds to the waits for their liveries, and in some instances they also carried scutcheons, or silver badges—further highlighting the similarity with modern-day police.

As late as Haydn’s day, the esteemed composer was expected to wear a uniform as part of his job as “Capellmeister of His Highness the Prince (Esterházy) in whose service I live and die”—that’s how Haydn described the position in a surviving letter. In his official costume, he looked like the leader of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Again and again, surviving accounts of medieval and Renaissance town musicians describe their attire. This was no small matter, because people judged a city by how well it outfitted its musicians. But other tiny details received equally close attention. In fact, almost every aspect of the minstrel’s trade had a symbolic importance—for example the Waits of London consisted of nine musicians, because that was the same number as the Muses of ancient lore.

We shouldn’t forget that civic musicians also provided entertainment—and not just for the ruling class. You could consider them as true public servants in this regard, at least judging by their responsibilities to perform for all and sundry. In Venice, the doge’s piffari would perform for an hour each day in the Piazza. Such public performances were common throughout the region, where piffari were a regular attraction in the town square—when they weren’t leading processions or adding to the spectacle of ceremonial occasions.

Montaigne writes of encountering them during his Italian trip of 1580-81, where the piffari played reveille for an hour in the morning and again in the evening on oboes and fifes. Benvenuto Cellini, the celebrated Italian artist and chronicler, tells of his father’s participation in such a local band—until Lorenzo de Medici tried to have him removed from this position because he feared the elder Cellini was neglecting his talent as an engineer.

Payment for these services was modest, but extra income might be made from playing at private banquets and weddings or taking on students. The standards of musicianship were often quite high—some street musicians were capable of playing almost any wind instrument, and many were also skilled singers—and acceptance into this coterie was not happenstance but eventually followed the paths of apprenticeship practiced by the guilds.

But modern life has different priorities. Consider the case of London, where there had once been those nine waits. They were still around in the early nineteenth century, but at that point a new rule was instituted requiring that only trumpeters be hired—probably a sign that the job was now mostly about playing ceremonial fanfares. But in 1854, the city decided to stop filling vacancies in the ensemble. Finally, the whole notion of city musicians was abandoned in 1914—with the proviso that London would borrow military trumpeters if and when they needed ceremonial music.

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised. But it does seem odd that today’s cities have much larger budgets, with hundreds or thousands of employees of all types—offering so many services that no medieval town would have even considered—but no longer employ those musicians who were once a focal point of such civic pride.

Even where I live—a city that brags that it is the “live music capital of the world”—musicians are still freelancers, not permanent employees. That slogan was adopted by Austin back in 1991, when a survey showed it had more music venues per capita than other cities. I certainly appreciate those clubs and their commitment to live entertainment. Even so, I’d love to see horn players at the Austin city limits, and minstrels strolling down Sixth Street.

After all, the other motto proclaimed proudly by locals here is “Keep Austin Weird”—and what could be weirder than bringing back musicians as hired first responders for riotous revelry? If they could do that in 1370, why not today?

I am an American expat living in the city of Bergen, Norway. One of the reasons I left a principal position in a prestigious American orchestra is that the Bergen Filharmoniske is still supported by the city. It is the second oldest continuously playing orchestra in the world at 253 years. Yes I pay about 5 percent more in taxes but my taxes go to support healthcare, education, public support programs and all facets of the arts. America could support the arts easily if corporations and the military industrial complex were no longer top priority.

Some friends and I sometimes play music in our local park, in what is a prosperous but culturally boring town (Americans would call it a city) in the midlands of England. Our efforts are always appreciated by passers by. Sadly, in England, the weather is often against us. I think it would be great if more people would do this.

Incidentally, for a taste of "municipal" music from 16th century Venice, try Giovanni Gabrielli's brass compositions. Typically for two antiphonal groups of four instruments, a music student friend once told me they were designed to be performed outdoors as well as in indoor church and municipal spaces. The effect of this in St Mark's Square must have been stunning.