Why Are Quiet Spaces Disappearing?

And how do we get them back?

A friend who travels regularly on Amtrak trains, told me about the Quiet Car. The rules are simple:

“Guests are asked to limit conversation and speak in subdued tones.”

“Phone calls are not allowed.”

“All portable electronic devices must be used with headphones.”

“Passengers using headphones must keep the volume low enough so that the audio cannot be heard by other passengers.”

My friend loves the Quiet Car. But there’s just one problem. It isn’t very quiet. Sometimes it’s just as noisy as the rest of the train—or even worse.

“People have no respect for the Quiet Car,” he laments.

If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription (just $6).

This isn’t an isolated situation. All our quiet spaces are getting noisier.

“When did museums stop being quiet spaces?” complains a Redditor:

I understand that museums are some of the best educational activities and affordable fun for the whole family. Children are allowed to be excited and express that, but when 200 families are at full volume at once it turns a museum lobby into a wind tunnel of sound. Maybe because I’m not a kid anymore, I notice it more? Was it always this loud?

Some museums even encourage the din. They tell families to bring their children—and get as noisy as possible.

But the most obvious place where silence is no longer golden is the library. Not long ago, these sanctuaries were so sacred that librarians became emblems of imposed silence.

Shushing was to a librarian what the Hippocratic oath was for a doctor—or maybe even more sacred. After all, physicians only utter their oath once, while librarians were constantly declaring sh-sh-sh-sh!

That was a great catchphrase, and served the public well. People go to libraries to study and read—so it really ought to be a quiet place.

I benefited enormously from these quiet spaces during my formative years. I’m certain that I learned more at the library than in the classroom.

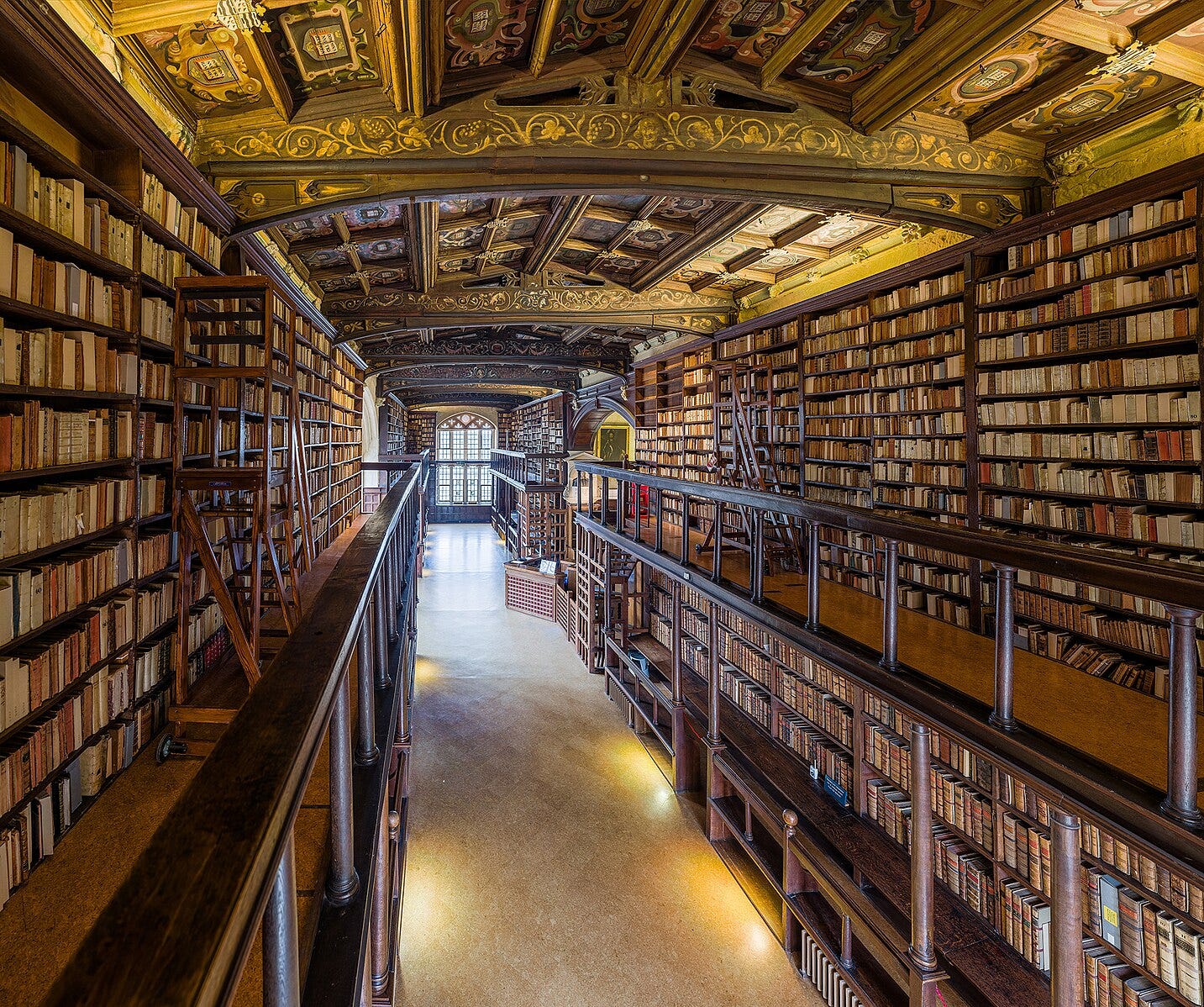

Just walking in the door of the Bodleian Library at Oxford was a special experience for me as a student. I felt like I was entering a fortress—where all seekers would be protected from every danger and distraction.

Once inside, you had access to a sacred inner sanctum of knowledge and learning. Something like this is even better than the Batcave.

Not long ago, even the humblest public library shared in this aura of reverence and sanctity. You didn’t need to be a duke or Oxford don or billionaire Bruce Wayne to enjoy it—it was now provided to everybody at the city’s expense.

So the shushing librarian became a cultural meme and comedy trope—and maybe even served as the unfortunate origin of the annoying Karen stereotypes of the current day. For example, when Bill Murray tries to talk to a librarian’s ghost in Ghostbusters, the apparition responds: Sh-sh-sh-sh!—before mounting a full-fledged paranormal attack.

That’s great for a laugh, but I now miss those shushing librarians. Libraries are no longer quiet places. They’re as noisy as the pub after a football match.

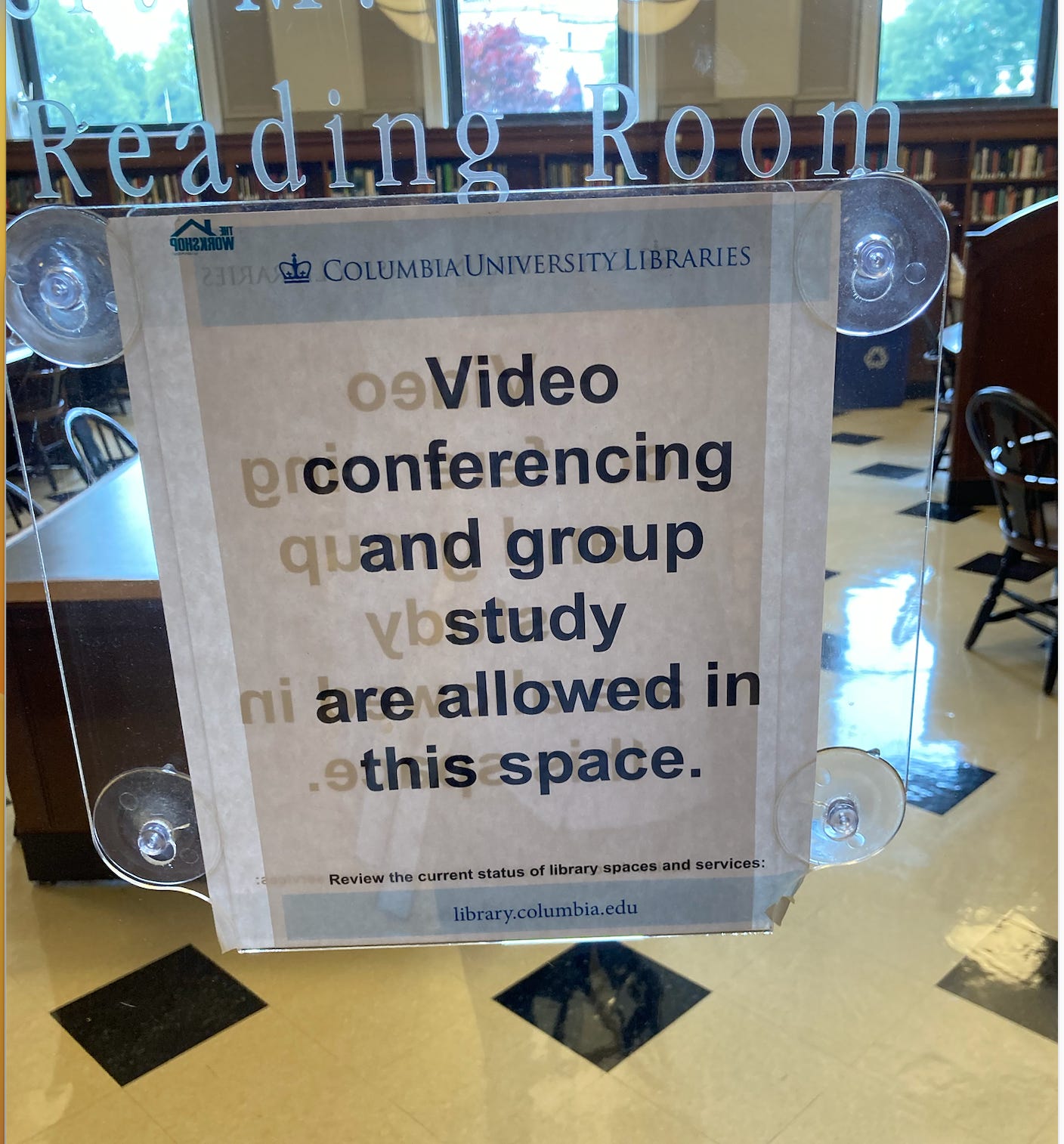

Books are removed, and replaced with coffee bars and spaces for socializing. In case people don’t get the message, librarians now put up signs discouraging quiet study.

Check out this “reading room” at Columbia University—at least that’s what the engraved words on the window proclaim. But an update pasted below tells people that they can expect video conferences and group conversations if they actually plan to read in the room.

But this raises an obvious question—if we lose libraries as the last public space for quiet reading and reflection, what can replace it?

Perhaps a few religious sanctuaries remain where quiet can be found. But can you really bring a book to the Christian Science Reading Room? Despite the name, I don’t think that’s allowed.

Why is this happening.

My friend who told me about the Amtrak Quiet Car offers a theory:

This all got worse after the pandemic. People spent months in isolation, and when they returned to public spaces, they had forgotten the basic rules of polite behavior in these communal settings.

They stopped using headphones. They did Zoom meetings on speaker phone. In general, they stopped worrying about intruding on other people’s quiet—and didn’t bother to restrain their behavior or devices.

This rudeness feeds on itself. If I go into a public setting where others are noisy, I feel no need to restrain myself. Just let it rip!

It’s like the broken windows theory of policing. According to this plausible hypothesis, settings marked by disorder invite more disorder. If litter is strewn on the ground, visitors are more likely to add to it. If everybody else is shouting, newcomers also start shouting. If the rest of the line is pushing and shoving, you will push back.

So violations of quiet spaces after the pandemic quickly escalate. And once we enter on this vicious cycle, the silence never returns.

There is still one last resort here—isolation. If I can’t trust others to restrain themselves, I must retreat to some place where I am totally alone.

Under ideal circumstances, that might lead us to return to the natural world—a forest, a garden, a meadow, a mountaintop. Or maybe we find our way to a hermitage or retreat.

That sounds great. But for most people, these options aren’t available. The only reliable isolation in modern urban life is less idyllic—you lock yourself away in your bedroom, or maybe a toilet stall.

The nature retreat or mountaintop hermitage is just too far away or too expensive. People can’t even afford the down payment, let alone ongoing operating costs.

We need something better. I suggested an option in my recent interview with Image Journal.

I have a musician friend who wrote a song called “Hermitage.” I heard him introduce it on the bandstand one night, and he felt obliged to explain what a hermitage was. After all, it’s not a word you hear often nowadays. He told the audience: “I should tell you what a hermitage is. It’s a place where people go to chill out.”

I laughed at that, but I like his definition.

We need places to chill out nowadays more than ever before. I’d even speculate that there’s a business opportunity here. Somebody should start a chain of hermitages—call them chillout centers or retreats or whatever. Demand will soon be off the charts.

It’s already happening. I hear from people every day who are fed up with their digitally driven lives. Just yesterday I was told that 40 percent of the public now tries to avoid hearing the news. Social media is no better. I’ve cut back sharply, and judging by the metrics many others have done the same. This movement will spread.

That is how silence will get reclaimed in our society. It will happen at the grass-roots level. People like you and me will find our own ways of chilling out. We don’t need to wait for permission from Silicon Valley.

Some people probably dismissed this as a joke. A chain of hermitages—really?

But I’m dead serious.

Both private and public life suffer when we are deprived of quiet spaces. Silence is the pathway to serenity. Without it, we grow anxious, irritable, depressed—and there are plenty of indicators that this is happening right now on a widespread level.

So let’s create new kinds of places for contemplation, meditation, or even reading and studying. And maybe we should reclaim some of the libraries and other traditional centers of silence along the way.

That’s easy enough to do.

Most of these are operated by schools and communities—and not profit-driven businesses. The last time I looked, there were no libraries or museums in the S&P 500. Alphabet and Meta have no influence in those spheres of tangible culture. So there’s nothing preventing these institutions from doing something for the good of the public.

That’s a lovely idea: Serving the public good. Maybe it deserves a comeback.

Yes, perhaps we will lose a few espresso bars if the libraries regain their status as sanctuaries of silence. But there’s so much more to gain by bringing back these shrines to sh-sh-sh.

Visitors might even decide to pick up a book.

You are spot on Ted. The problem is everywhere.

I use public transit when I am in Vancouver. On a trip up to UBC a passenger was listening to their phone without headphones. The driver stopped the bus between spots, got out of his seat, walked to the back and said, put the headphones in or shut off the phone, and went back to his seat and continued the journey. And the guilty party compiled.

I took courage from his example and done the same on planes, buses and in public spaces. I make my request politely but firmly and folks seem surprised but willing to comply.

We don't need more of new quiet spaces, we need t protect the ones we have.

Just having returned from Switzerland, I am happy to report that some countries do take the importance of quiet to a national level. Swiss regulations state that residents are to "observe hours of peace and quiet" not only during the night, but also from 12 to 2 pm. During this midday break people are expected to refrain from vacuuming, playing musical instruments, hammering, etc and must keep television and radio noise at room levels. These rules may seem intrusive, but offer a collective effort to give people a period of quiet reprieve in the middle of the day. There is a reason visitors to Switzerland perceive it as such a peaceful place :)