Where Did Musicology Come From?

I share an extract from my new book 'Music to Raise the Dead'

Below I share a new extract from my book Music to Raise the Dead.

Each chapter can be read on its own. But if you want to check out the rest of the book, click here for an overview and links to each section.

I’m publishing this entire book on Substack for my subscribers—at the rate of one chapter per month.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Where Did Musicology Come From? (Part 1 of 2)

By Ted Gioia

Musicology originated as the study of magical incantations. You probably haven’t heard that before. And for a good reason: They don’t teach this stuff in music schools.

It’s too embarrassing. Too shameful. Too unsettling.

Juilliard is not Hogwarts, my friends.

Even worse, the magical underpinnings of music have been so censored over the centuries, that most of the evidence has been hidden from view—and sometimes intentionally destroyed. It’s not easy to piece this story together. When I say that I’m sharing a secret history, I’m hardly exaggerating.

But the evidence we’ve examined so far in this book makes these magical connections abundantly clear. From the beginnings of human history magic was embedded in songs. The most powerful magic is always sung or chanted.

That was even true for the oldest hunter-gatherer tribes. We know that because the magical images on the cave walls are always located in spots with the best acoustics. Our ancestors needed to sing or chant in order to tap into higher powers or altered mindstates.

And we found the same thing when we analyzed the Derveni papyrus, the oldest book in Europe. We learned, to our surprise, that this book of ritualistic magic is actually a musicology text, despite the fact that only scholars of ancient philosophy or religion take this work seriously. These hymns, and the remarkable claims made for them by the author of the papyrus, have shaken up the world of classical studies—but musicologists are blissfully unaware that this document even exists.

And we learned the same thing when we peered into the origins of the musical conductor—and actually discovered that the conductor’s baton was initially a magic wand.

And we’ve encountered similar magical underpinnings to music in hundreds of other places, from shamans in Siberia to the lore of Celtic bards.

All this is an embarrassment to the musical establishment. But it really shouldn’t be. Because we have also demonstrated how much hard science supports all the old myths about the transformative power of music.

That’s what makes this book so strange. It’s half superstition and half science. And those two worldviews intersect.

That shouldn’t be possible. Magic and science are total opposites. They shouldn’t rub shoulders. But music is the place where that strange meeting actually happens—in fact, an aware musician is always operating at a kind of crossroads where the known world meets a mystical realm. And that happens constantly, not just in ancient times but even today.

This is no empty claim. You feel it when you listen to music—perhaps not everyday, but at least on a few transformative occasions, maybe at a memorable concert you still think about years later, or at a dance or party or ritual. That’s why musicology, esteemed as the science of music, must also learn to embrace the ecstasy of music.

Musicology really ought to be a science of ecstasy. But instead, this magical stuff is feared and censored. That’s why conventional musicology is at a loss when dealing with the mystical writings of Sun Ra (which we discussed in chapter one). That’s why scholars try to sanitize the story of blues legend Robert Johnson, whose mythos has such deep supernatural elements. That’s why they gape in disbelief when I point out that the oldest active jazz venue in San Francisco is the Church of John Coltrane.

It’s no coincidence that we find ourselves discussing churches at this stage. That’s because magic and religion also intersect—and their dialectical merging is a crucial part of understanding the true scope of musicology.

At a certain point in human history, magical spells turned into prayers and religious music. You might think that those two things are very different, but they’re almost the same. Sometimes it’s very difficult to distinguish between a magic spell and a religious prayer. If you examine the history of witchcraft, you will learn that judges often made decisions of life or death on the basis of tiny word differences.

Sometimes inserting the name of Jesus or the Virgin Mary in the middle of a spell was enough to make it acceptable to authorities. But not always. As we shall see later in this book, many people were condemned as witches even though they thought they were aligned with formal Christian theology and practice.

This is a good juncture for us to look at how the hero’s journey—which is the central myth of musical magic—got turned into a religious concept. The oldest sources for musicology focus on this journey, which predates all organized religions but also permeates them. Sonatas and fugues and symphonies (and other formal structures) came later, but they retain these mythical and religious evocations.

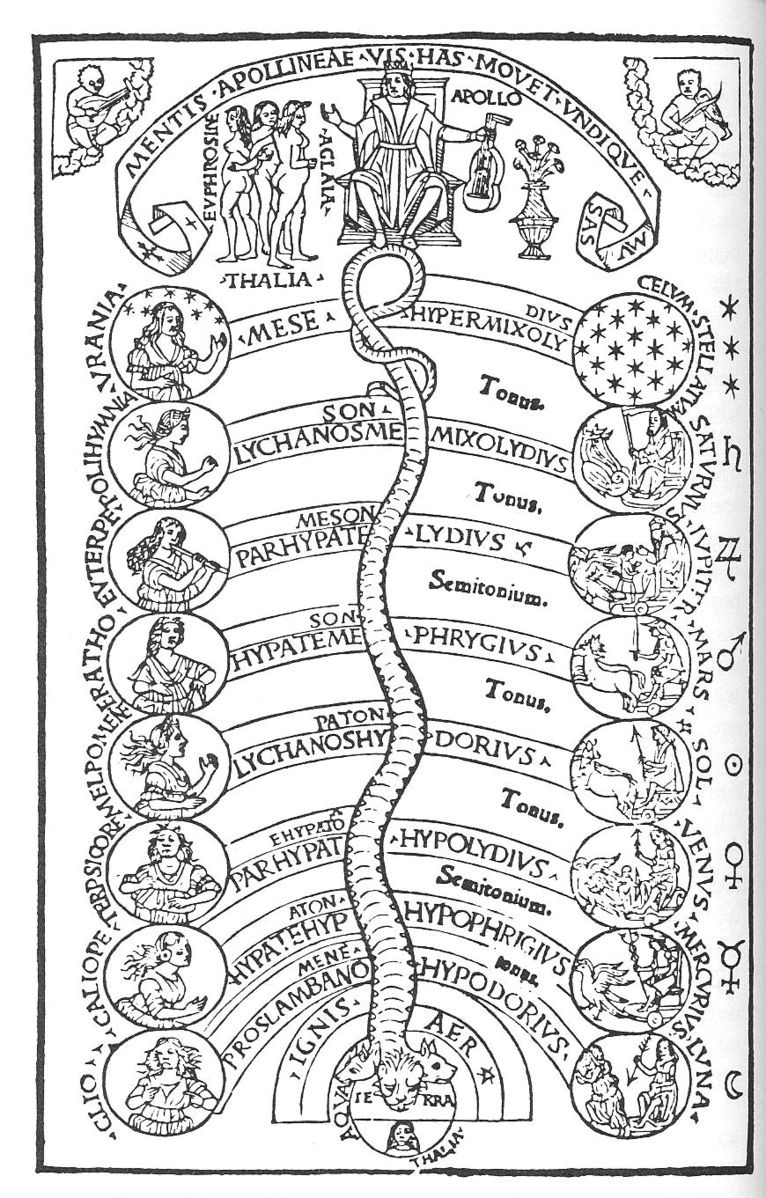

That’s why the earliest theoretical commentaries on music—which are essentially guides to this journey—are permeated with metaphysics. The science of harmony didn’t exist at this early juncture. Or, to put it a better way, harmony was a much larger concept in this musicology than just the ways the notes fit together.

I could demonstrate this in many ways. For example, I could point to remarkable passages in Augustine’s Confessions where he describes ecstatic experiences, merging intense joy and painful hardship, that are almost like a Christianized shamanism—and they are initiated by singing or chanting the psalms. Or I could cite countless Pythagorean or Neo-Pythagorean texts on music that aspire to scientific accuracy, but keep on collapsing into the strangest mysticism. Or I could explore similar elements in Sufism and its whirling dances, or Tibetan Buddhism and its chanting and damaru drumming, or the ritualistic theurgy of the Neoplatonists.

Each of these is loaded to the hilt with musical pathways that align in uncanny ways with the science and mythos I’m explicating here. Harmony in these contexts is celestial, and not reducible to black and white notes on a page. For practitioners of these disciplines, music empowers the celestial journey.

I could use any of these as an entry point into the inner life of musicology, but instead I will focus on a different religious tradition. It was formulated by some of the deepest religious thinkers in human history, who obsessively fixated on this same magical mystery tour. They collectively devoted 500 years to studying it. And the first thing you will notice is its striking congruence with the blues mythos and Native American belief systems we just looked at in chapter four.

The approach I’m referencing is known as Merkabah mysticism, and it’s a Jewish tradition even older than Kabbalah. You might even say it’s the oldest Jewish mystical tradition, with the exception of the actual experiences of the prophets.

Most of the key texts in this tradition date back 1500 to 2000 years. Many have survived in fragments, and we often lack even the most basic information about them—not only how and when they were written, but even the identities of the authors.

In some instances, the wisdom contained in the text is assigned to a familiar name, but this is hardly a sign of genuine authorship. We encountered the same thing, you may recall, in the old Greek documents attributed to the mythic figure Orpheus, or the Egyptian Book of the Dead, where the deceased is often called by the name of the god Osiris—you take on the identity of the exemplary figure in order to participate in their extraordinary powers.

Scholars hate this confusion, and they use it as a reason to marginalize or ignore such texts. And who can blame them? When we encounter a text attributed incorrectly (by contemporary standards), we consider it a forgery or plagiarism. Its value is lessened in the eyes of academics, trained on precise footnotes and bibliographies, who want the real thing, not some pretend document with a fake attribution. Yet this misses the point. The very fact that these authors suppressed their own names in order to identify with a legendary predecessor tells us how seriously they took their project. If you had any doubts about the significance of Orpheus, for example, this continued identification between disciple and role model, persisting over centuries, testifies to exactly how important he was.

But is this all so different from our other heroes—even those in pop culture? Consider the case of James Bond. Sean Connery is dead, but James Bond never dies, merely finds new incarnations (Roger Moore, Daniel Craig, etc.). That's almost the definition of the hero—the protagonist who always triumphs even in the deadliest circumstances, never really disappearing. And it always involves, sooner or later, a return from the dead, even in its secular versions.

In fact, as I write this, the most recent James Bond film is No Time to Die, which ends with the death of James Bond. But they’re already looking to cast a new James Bond. He will return from the great beyond—that’s what heroes always do. And even if his face and features change, the James Bond theme song—a quasi-magical incantation that audiences will always insist on hearing—will remain the same.

It’s not much different than Orpheus. They both return from the Underworld with their powerful song. Only the box office receipts are different.

You could imagine cultural historians, thousands of years from now, trying to figure out the birth and death dates of historical figures named James Bond or Sherlock Holmes or Indiana Jones (or some other brand franchise) based on scraps of evidence. They would be forced to conclude that these individuals—elites whom we call heroes—were actually gods or immortals who thus never died, or perhaps flesh-and-blood innovators that later plagiarists and forgers adopted as their own names.

The same confusion surrounds Rabbi Ishmael and Rabbi Akiva, the two heroes who guide us on the journey in Merkabah literature. They are a cross between historical sages and legendary protagonists of the realm beyond. We would like to know more about their biographies, but this is a situation in which details about the real flesh-and-blood person are less significant than their larger-than-life symbolic value as guides to a reality beyond the merely human.

We are fortunate that we possess any of this literature, because the mystical relationship with the Merkabah—the divine chariot or throne—was shrouded in utmost secrecy. Perhaps the persecutions of that era led practitioners of these visionary techniques to put down on paper things they would have rather kept to a small circle of followers, if only because they feared their wisdom might otherwise disappear entirely. When Rabbi Ishmael, we are told in the Pirkei Hekhalot, “saw Rome was planning to destroy the mighty of Israel, he at once revealed the secret of the world.” Whatever the reason, the Merkabah tradition has every mark of an insider’s practice, not meant for widespread dissemination and proselytization.

And what was this “secret of the world”? Strange to say, it consisted of instructions on how to take a dangerous journey. This hardly seems like a promising field for a religious practice. Don’t those people just pray and meditate? And earlier Jewish texts were already full of instructions—they represent a significant portion of scripture—and believers had no shortage of rules for everyday life.

Despite what you may have heard about the Ten Commandments, there are actually 613 regulations in the Torah, according to experts who have bothered to count them. Isn’t that enough?

No, not for the Merkabah mystics.

Even more to the point, why would any religion need rules for a travel itinerary? But, as noted, the very name Merkabah describes the mode of transport, namely a chariot—the focal point of an intense 500-year religious tradition. But this is only puzzling to modern thinkers, who see no connection between a chariot and spiritual transformation. But any scholar focused on old ancient religious practices will hardly be surprised.

That’s because magical, musical chariots are everywhere in the early history of religion….

Click here for the second half of “Where Did Musicology Come From?”—where I outline the 8 steps of a true hero’s journey, and their musical connections. It’s very different from all those hero stories concocted by Hollywood.

Footnotes:

magical images on the cave walls: Iegor Reznikoff, “Sound Resonance in Prehistoric Times: A Study of Paleolithic Painted Caves and Rocks,” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 123, no. 5 (2008), pp. 4136–4141. Iegor Reznikoff and Michel Dauvois, “La dimension sonore des grottes ornées,” Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, vol. 85, no. 8 (1988), pp. 238–246. See also Ted Gioia, Music: A Subversive History (New York: Basic Books, 2019), pp. 28-29, and Ted Gioia, Work Songs (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006). pp. 13-15.

magical spells turned into prayers: Ted Gioia, Healing Songs (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), pp. 13-15.

remarkable passages in Augustine’s Confessions: The Confessions of Saint Augustine, translated by J.M. Lelen (New York: Catholic Book Publishing, 1952), pp. 206-210, pp. 265-267.

saw Rome was planning to destroy: Pirkei Hekhalot, translated by L. Grodner, in Understanding Jewish Mysticism: A Source Reader, edited by David R. Blumenthal (New York: Ktav, 1978), p. 56.

Thanks for this fantastic excerpt. It reminded me of learning a few polyphonic traditional Georgian songs, where the tones and the words lure the sickness from a patient's body, and encourage it via an aural trail of rose petals towards an open window, and back out into the landscape. And the fact that so many of the stone circles I have been to in Aberdeenshire have incredible aural properties and foci right by the huge recumbent stone, (similarly in our chambered cairns). Looking forward to the rest of the book.

Not being steeped in any religion my ideas of spirituality come primarily from listening to and writing music. The joy's of singing in groups or just sitting with a guitar is my idea of heaven.

The one time I saw Prince perform was during his Musicology tour. He reminded everyone where the foundations of his extraordinary gifts in music came from. I for one, singing with 15 thousand other voices at the end of Purple Rain experienced once again the kind of magical healing that music can bring. I am ever grateful for those moments.