When They Had a Contest to Rename Jazz

The results were ridiculous, but also revealing

I sometimes hear from jazz fans who love the music, but hate the name.

Their reasons are varied, and often based on incorrect information—no, jazz did not originate as a term for sex, despite what you may have heard—but their anxiety is no joke. Sooner of later, they come up with a exciting new idea, namely to rebrand ‘jazz’ with a better identity.

I’m highly skeptical of such plans, and have written elsewhere about my own painful but illuminating experiences with rebranding. My (perhaps cynical) take is that the urgency to find a new name is, in every instance, a substitute for addressing some other, deeper issue.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, and culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Go ahead and give Godzilla a new name. But if he keeps on destroying Tokyo, that image remake won’t last.

It’s not just jazz. A few days ago, a journalist sent me an email with one question—would I comment on the obvious need for a new name for rock music. I was dumbfounded. Was this a thing? But then I realized that fringe masterminds in every genre, from classical to country to Gregorian chant, probably believe that a new name will bring in millions of additional fans.

After mulling it over, all I could say was that the rock debate seemed pointless. Journalists can write whatever they want, but rock and roll will never die—at least as a name for a genre.

But more to the point, these agonized attempts to rebrand a music genre aren’t a new idea. People have been hatching plans to rename jazz for more than 70 years.

A recent rebranding proposal aims to rename jazz as BAM (or Black American Music). I’m a little hazy at how this would actually be put into practice. Aren’t there other genres with equally valid claims—or perhaps even better ones—to the status of Black American Music, whether we’re talking soul, blues, hip-hop, spirituals, R&B, or a host of other significant idioms. Shouldn’t jazz at least share the BAM label with other styles?

But even more confusing is how current-day jazz releases from Europe, Asia, Africa, etc. fit into this scheme. The Nordic jazz of Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek is obviously jazz, but can it really be called Black American Music? Or what about the rest of those globe-spanning ECM albums, or how about those London jazz bands with deep African and Indian roots, but not much of an American pedigree? Or what about the booming jazz scenes in Japan or Johannesburg or Jakarta or wherever—how BAM-ish are they?

As far as I can see, the existing word jazz does a better job of fostering this diversity than the narrower BAM label. But given my low level of interest in any rebranding exercise, I should probably let others debate these points.

In an odd way, the BAM advocates remind me of Stan Kenton, who led one of the most influential modern jazz big bands from the 1940s through the 1970s , but clearly hated the terms modern jazz or bebop. Instead he kept coming up with alternatives. In some instances, he called himself a practitioner of Neophonic Music or Progressive Jazz or—most cumbersome of all—New Concepts of Artistry in Rhythm (no, not quite NARC, which would have been amusing, but close to it). These endeavors might have generated a few write-ups in the press—and all publicity is good publicity, or so I’m told—but they never stuck.

Nor will any of the other alternatives, I’m convinced. They make for good marketing copy and interview fodder, but not much more.

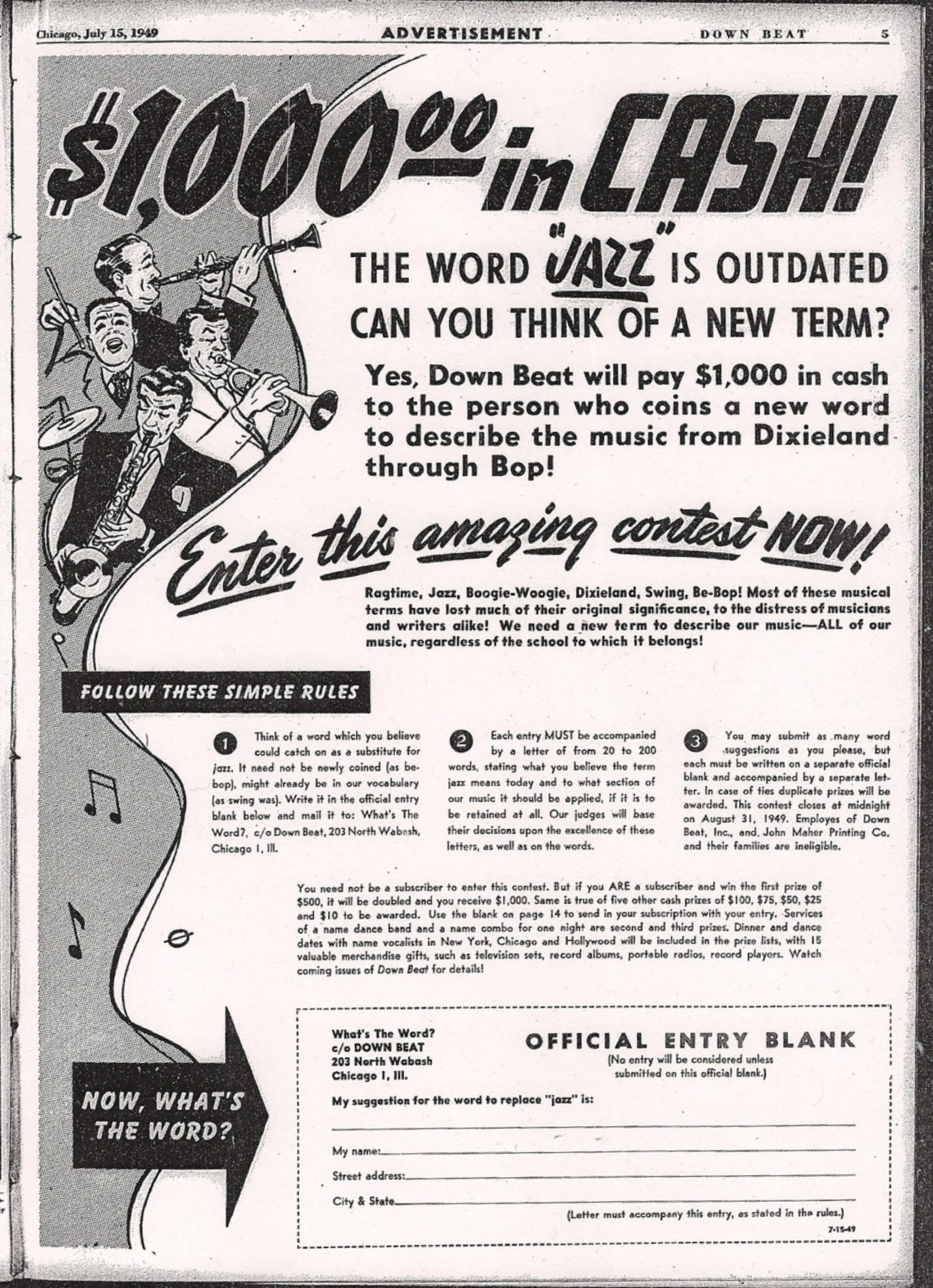

The most intriguing of these efforts is one that’s almost completely forgotten nowadays. But in 1949, Down Beat magazine launched a contest to find a better name for jazz. And to certify the seriousness of the plan, the periodical offered a thousand dollar prize. That’s more than $10,000 in current purchasing power. The minimum wage was just forty cents per hour back then, and a typical household might get by on three thousand dollars per year. So a thousand dollar prize was a big deal.

“Jazz fans and the Down Beat judges didn’t really want a good marketing name, they actually craved respectability instead.”

Even so, it’s tempting to laugh at Down Beat’s contest, although the magazine had genuine reasons for concern. Jazz had flourished as the most popular music in America during the late 1930s and early 1940s, but by 1949 its audience was clearly shrinking. Big bands were breaking up because there weren’t enough gigs. Ballrooms were shutting down, as dance floors lost their allure. Other styles of music were climbing the charts, replacing even the most tried-and-true jazz stars of the previous era. Down Beat must have felt the pinch too.

There was a small catch to the contest (isn’t there always?): the cash prize would be cut in half if the winner wasn’t a subscriber to the magazine. So anyone who had a great idea for rebranding jazz really needed to take out a subscription to maximize the potential return. The publisher probably believed the contest would pay for itself.

Even so, what an intriguing idea—and why not have a contest to rename jazz? Maybe some amazing new identity was out there just waiting to be discovered.

Sad to say, the results were embarrassingly bad, and for the most predictable of reasons. Even though demand for jazz was declining in the marketplace, jazz fans and the Down Beat judges didn’t really want a good marketing name, they actually craved respectability instead. Rather than picking a name that signaled how much enjoyment you can get from jazz, they preferred some label that catered to their elitist tendencies.

So the judges eliminated the fun names offered by fans—which included “Mop,” “Schmoosic,” “Jarb,” and “Blip.” You may think that those are ridiculous terms, but stop for a moment and recall the seemingly idiotic names that successful web platforms have adopted (Google, Twitter, Yahoo, Reddit, Alibaba, TikTok, etc.) on their path to riches and dominance. Or consider how, fifteen years after the Down Beat contest, the popular music world was taken over by bands with silly names—I’ll start with the Beatles, with its deliberate misspelling of a group of insects, but I don’t even need to list other examples. You already know dozens of them.

Even jazz started out as a silly name, originating as a slang term for any thing new, exciting, offbeat, and outside the norm. In other words, jazz wasn’t much different from Google or the Beatles in its connotations. The idea was to promote enjoyment. Silly names are popular because they convey a sense of informality and fun.

But jazz fans, circa 1949 (and maybe still today), wanted something more respectable. And they got it in the winning name, as chosen by Down Beat.

The winner of the contest was (we open the envelope and stare in disbelief): Crewcut.

Crewcut?

Yes, crewcut. What could be cleaner or neater or more respectable?

For those unfamiliar with the history of barbering, I’ll point out that the crewcut originated with the crew (or rowing) teams at Harvard and Yale, and was a neat, ultrashort style that reduced wind resistance in a race. It was also associated with the soldiers who fought in World War II—so that when you saw a civilian with a crewcut you assumed he had served in the military.

Ah, nothing quite conveys the essence of jazz as the Ivy League, rowing, neatness, and army life.

The winner, Esther Whitefield of Hollywood, got paid a thousand dollars, but the winning name was quickly forgotten. I’ve never ever heard anyone refer to jazz music as crewcut, and if anyone did, no one would understand it. But the contest did have some value—it testified to the neuroses and anxieties of many music fans, who are afraid that their favorite genre lacks an identity that forces others to bow down and pay homage. I feel that those other suggested names over the years have the same intention.

Frankly, I don’t worry anymore about jazz getting respect. It is now entrenched at Harvard and Juilliard and Lincoln Center. It gets Pulitzer Prizes and PBS documentaries and special events at the White House. There’s no shortage of respect for jazz.

I’d rather convince people how much fun this music is—the same today as back when Buddy Bolden originated it with his song “Funky Butt.” No, that’s not a very respectable name for a song either, but Buddy Bolden knew something we shouldn’t forget. He knew that the music ought to be edgy and unpredictable and exciting and genuinely fun. He didn’t want people to bow down in respect, but get up and dance.

With that in mind, I’m perfectly happy to keep on calling it jazz.

I've never been a fan of smooth crew cut. I like bop crewcut and there's nothing like a good old standard crew cut. But give me good old straight ahead crew cut every time. That's the sound for me. I'm having to admit that I'm struggling with the concept of an afro-cuban crew cut. I guess downbeat will have to figure that out.

Ted gets it right. Let’s support music we love, and if it is called jazz, celebrate it! I can hardly wait to go into town next week to see and hear Christian McBride and his current ensemble at…Jazz Alley!