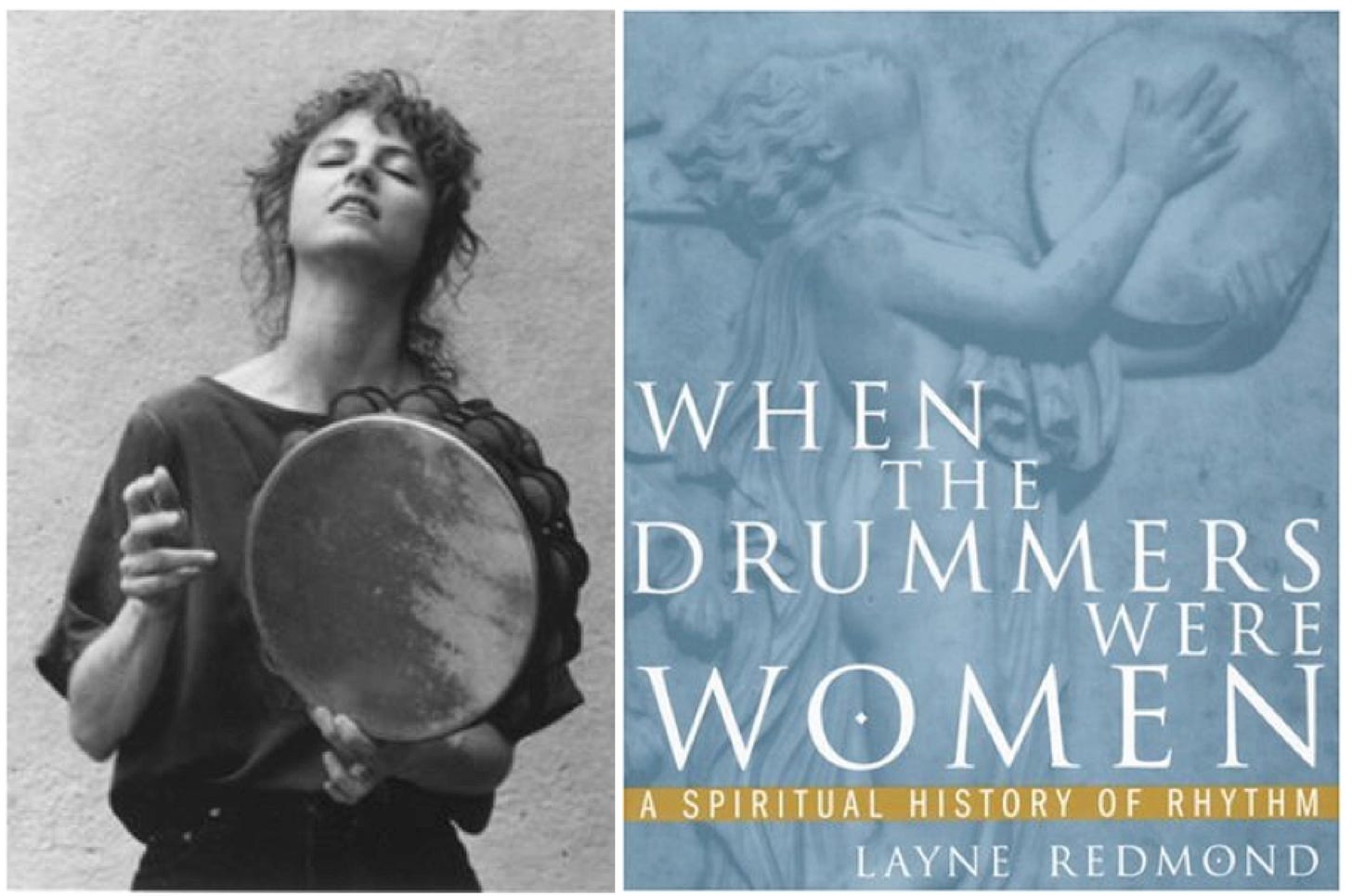

When the Drummers Were Women

I celebrate the legacy of Layne Redmond (1952-2013)—drummer, scholar, teacher, and visionary

Background: This is the fourth in my series of profiles of innovators I call sound wizards—those rare individuals who celebrate music as much more than entertainment or even art, but as something genuinely transformative in human life.

Many of these individuals are little-known or, in some instances, completely left out of music history books. But they have served as important touchstones for me over the course of many years, shaping my concepts and priorities about music.

In previous installments, I’ve written about Charles Kellogg, Hermeto Pascoal, and Raymond Scott. Below I explore the legacy of Layne Redmond (1952-2013).

On a separate note, paid subscribers to The Honest Broker will soon receive the second installment (out of three) of my guide to the top 100 movie soundtracks of all time. If you want to support my work, consider taking out a paid subscription and thus enjoy this survey of outstanding film scores (and other bonuses).

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported newsletter. Both free and paid subscriptions are available.

When the Drummers Were Women

By Ted Gioia

In February 2000, Drum! magazine decided to inaugurate the new century with a list of percussionists at the forefront of contemporary music. Most of the names were familiar to music fans, many of them genuine superstars. But there was only one woman on the list of 53 artists. Just as anomalous, she was the only musician featured in the article who had never played in a famous band—whether, rock, jazz, pop, or any other genre.

Even Layne Redmond’s drum kit was unconventional—because it wasn’t a kit. Redmond specialized in the frame drum, a circular handheld instrument, roughly the size of a hubcap and about the thickness of an apple pie. Needless to say, the frame drum is not the right choice for percussionists embarking on a music career. Not only won’t you gain fame and fortune, you might not get any gigs at all.

Go check out the Billboard Top 100 and tell me how many of those albums feature frame drums anchoring the rhythm section. I’ll wait for your answer. Or, better, I’ll save you the trouble. The answer is zero. Just as it was last month and last year. Just as it will be next month and next year.

It’s easy to laugh at the frame drum. In fact, the most familiar frame drum in pop music, the tambourine, is often the subject of jokes—surpassed only by the cowbell on the hierarchy of scorn and shame The tambourine is something a singer without any drum training might pick up and play behind a guitar solo, just to have something to do during the instrumentals. You wouldn’t specialize in the tambourine, merely play around with it.

Or so we’re led to believe.

But the frame drum has an advantage no other instrument in the band can match. It’s one of the oldest drums in the world, maybe even the first, and boasts a long, illustrious tradition that can be traced in every part of the world. And in many of these settings, the frame drum is linked to powerful rituals and important communal activities.

Much of what we know about this is due to Layne Redmond. Because in addition to her legacy as a performer, she undertook one of the most revelatory research projects in the history of drumming. She spent years uncovering ancient traditions, and analyzing their significance. Many people call her a scholar—and that’s not an inappropriate title. But perhaps it’s better to call her a teacher. That might seem a more humble vocation, but is it really? The scholar uncovers information, sometimes for its own sake. The teacher wants to change lives, and must convert information into wisdom and genuine skills. That was definitely Layne Redmond’s mission in life.

Even more to the point, Redmond called attention to something few scholars of ancient music have bothered to consider—namely, that the oldest traditions of frame drumming were originally associated with powerful women, and embedded into belief systems centered on femininity, fertility, goddesses, and reverence for the maternal. This rich subject was the focal point for Redmond’s most famous work, the book When the Drummers Were Women: A Spiritual History of Rhythm.

Redmond had identified perhaps the most significant point of rupture in music history. During a distant period of cultural upheaval, drums were taken over by men—and not just by male musicians. Drumming was especially favored by military organizations, who realized that this instrument could solve so many organizational problems. Drums instilled discipline into marching soldiers. Drums made opposing troops fearful, their very sound inspiring terror. Drums could be used to send signals and coded messages, identify locations and geographical directions, and provide other informational needs.

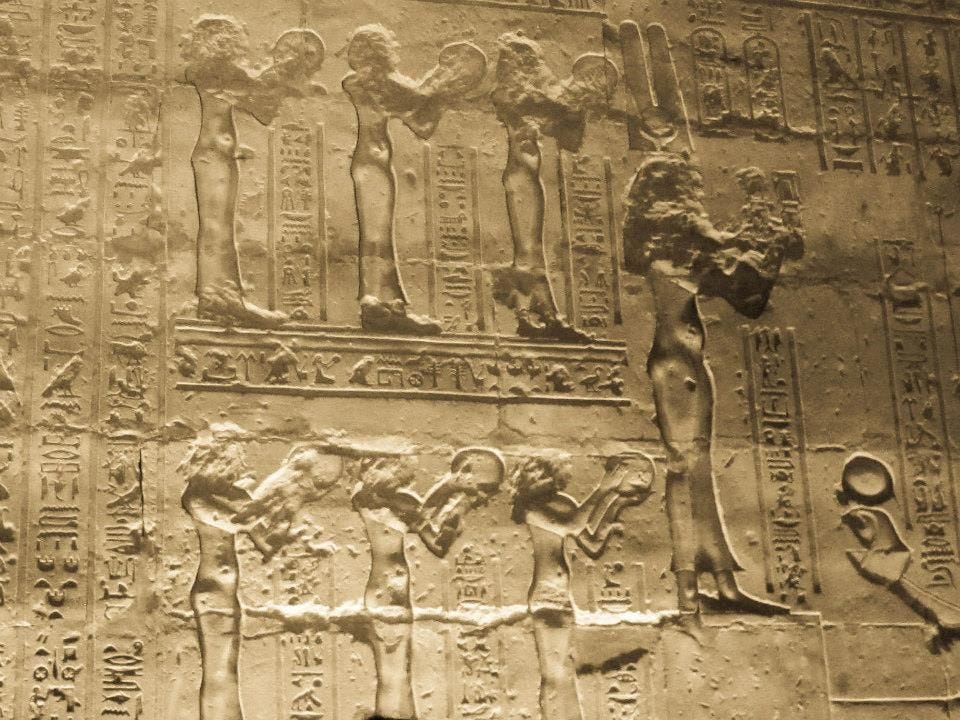

Yet there was an earlier stage in the history of music and society, Redmond hypothesized, when drumming had been more peaceful—a distant age when women had served as the awe-inspiring custodians of drums and their powers. The role of music was much different back then. When women set the beat, drumming was about fertility, abundance, prosperity, spirituality, and service to higher powers, many of them goddesses.

And the drums that did this were almost always frame drums. This small, seemingly insignificant instrument, as Redmond discovered, “is mentioned in the earliest surviving written texts from Sumer in the Tigris-Euphrates River Valley. From Egypt to the Indus River Valley, from Cyprus and Crete to Greece and Rome, priestesses and other worshipping women used the frame drum to celebrate their goddesses as the endlessly rhythmic energy of life.”

Redmond’s biggest impact, however, may have came via her interpretation of a wall painting in a shrine room at Çatal Hüyük, a neolithic age settlement in present-day Turkey that flourished from roughly 7100 BC to 5700 BC. The image depicts a group of people playing percussion instruments and dressed in leopard skins dancing around a stag, while a second group of dancers surround a large bull. One of dancers in this ritual seems to be holding a frame drum in one hand, and an instrument made from an animal horn (literally the source of the first musical horns) in the other. This was, Redmond believed, the oldest surviving depiction of a frame drum in human history—dating back some eight thousand years. Redmond stated, with some confidence, that the dancers were participating in a shamanistic ritual, and speculated that the shrine room might have been used for childbirth or rites of passage.

Redmond believed that the frame drum was held in special reverence because its rhythms echoed the organic pulse of life—in our blood, in the recurring cycles of our days and months, even originally in our mother’s heartbeat. She noticed how these drums were often painted in vivid colors, and believed that the vibrant reds were connected to blood, and the greens linked to vegetation of the earth. Drums of this sort were music and symbol and magic all rolled into one.

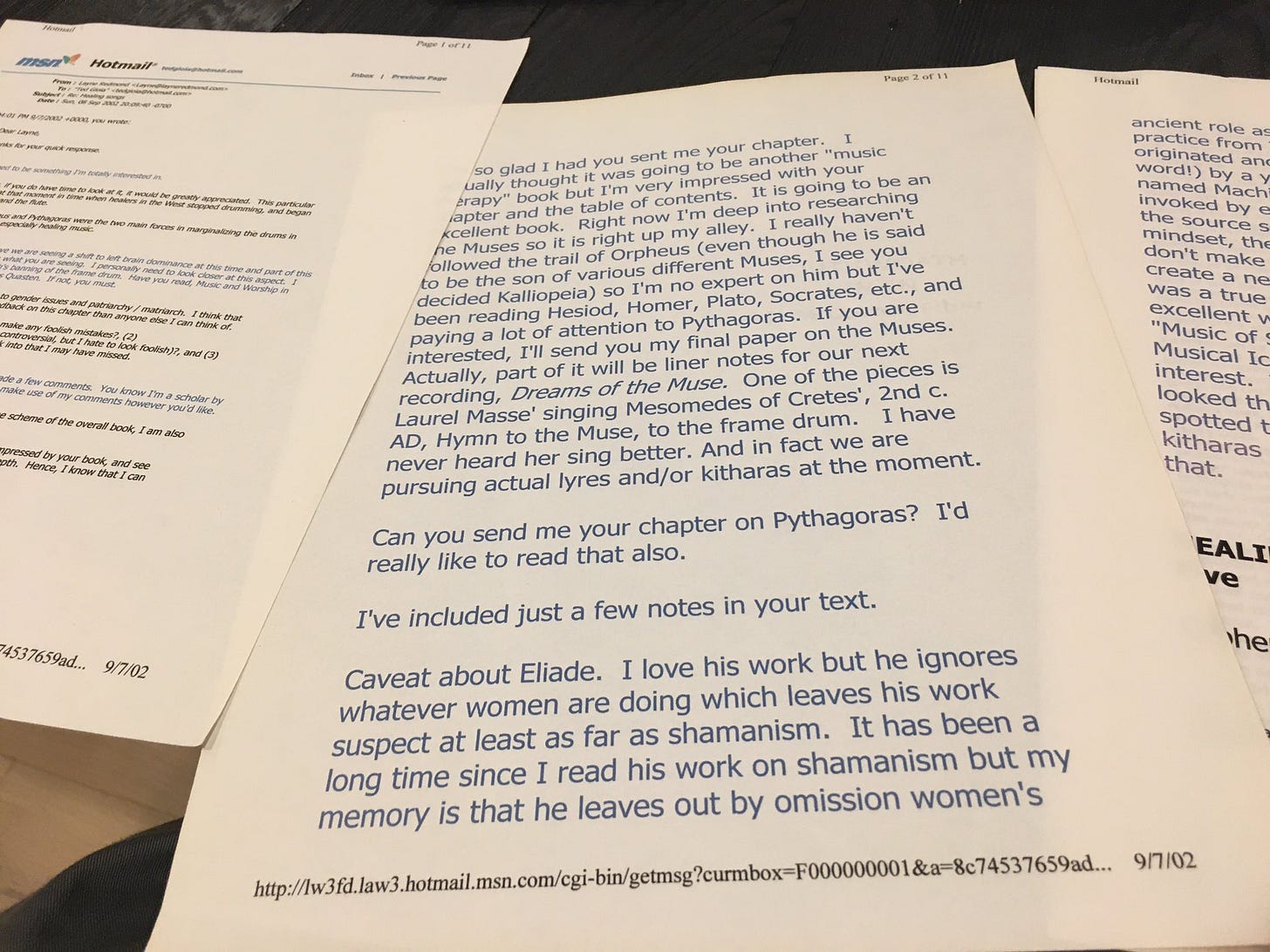

I remember how excited I was when I first encountered Redmond’s research—so I reached out to her to share information. This would have been around ten years before her death in 2013. We never met, but corresponded by post and email. I had reached similar conclusions, but starting from a different path. I had focused on ancient texts in a range of fields—works on philosophy, magic, religion, and mythology, supplemented by epic and lyric literature (which were originally songs before they were texts). Redmond, in contrast, had focused more on archaeological evidence and ancient art, augmented by her own rich experiences of drumming in alternative or ritualistic settings. She was enthusiastic about my research into Pythagorean traditions, not covered in her book, and I was tremendously inspired by the evidence she had gathered from the visual arts.

In my research, I had been reconstructing the musical roots of something I called “the Pythagorean rupture”—which involved a shift from a previous Orphic approach to song (magical, ritualistic, ecstatic) to a more codified Pythagorean system (rational, mathematical, disciplined). I now saw that Redmond had identified the same historical transition, but from the perspective of drumming and archaeology. We were both working toward integrating our hypotheses about music into larger sociohistorical theories of goddess cults and pre-patriarchic worldviews.

In other words, the most significant shift in ancient history had been signaled by a change in musical practices. It might not be going too far as to say that music set the beat for the dramatic changes that established the Western world, with its reverence for logic, philosophical discourse, and the codification of social practices. I’m still pursuing the implications of this in my research today, but Redmond provided some of the key pieces in the puzzle.

We both also shared an outsider’s status. I had a stack of degrees, but none of them in music. Redmond, for her part, had created a rich scholarly perspective with virtually no institutional support, or with any of the credentials academics put on their walls and CVs. And the more I learned of her background, the more impressed I was by her achievements, which testified to extraordinary skills of self-reliance and independent thinking.

Consider this unlikely career path. Although Redmond was born in 1952, she didn’t embark upon drumming until 1980! She grew up in western Florida, in a small, isolated community, and her early years found her focusing on dancing and cheerleading. It would be easy to dismiss these pursuits in the life of a master drummer and teacher, but Redmond herself gave them full credit. “In the rural South,” she later explained, “the football game is the biggest thing going in the county. I was using rhythmic movement and chanting to rouse and shape the group energies of hundreds of people.” As she later saw it, this was actually a useful starting point for her later immersion in frame drumming and ritualistic, transformative music.

After graduating from the University of Florida, Redmond traveled to New York—but to pursue a career in art, not music. Once again, this probably had a positive long-term impact, given how much her later research into the early history of drumming relied upon ancient paintings and sculpture. Even so, this whole period represents the most unusual vocational training of any drummer I’ve encountered.

An unexpected turning point happened in 1980, when Redmond signed up for an 8-week conga drumming class. Yet, for someone approaching the age of thirty, this must seem like too little, too late. Maybe not even that. After all, it was a class for hobbyists and part-timers, not aspiring professionals. But at the last class session, the teacher invited percussionist Glen Velez into the classroom as a guest performer. Velez played a Brazilian tambourine that day, and talked about how much he liked these handheld instruments, known as frame drums. Redmond jotted down Velez’s address at the end of the class, and thought it might be worthwhile taking lessons from him. But she soon forgot about it, and about drumming in general. The conga teacher moved to California, and Redmond was now working on multimedia installations to advance her career as a visual artist.

But, a short while later, she heard about a concert Velez was giving, and after watching him perform, she felt the urge to return to drumming. She started taking weekly lessons with him, and soon advanced to the stage of performing with Velez in concert.

“In some ways my lack of experience served me well,” she later claimed. “Glen was beginning to create complex pieces centered around unusual rhythmic patterns—cycles of ten, nine and eight beats, and so on. If I had spent years playing music based on traditional four-beat rhythms, I might have had a hard time adjusting. Instead I found that seven-, five-, or even thirty-seven beat cycles weren’t that tough for me.”

There are many lessons to learn from these formative experiences. First, Redmond never felt intimidated or discouraged on her creative path, despite having tremendous disadvantages in her training and environment. Second, she always looked for ways to turn her limitations and obstacles into advantages. Third, she constantly considered musical matters from standpoints that would never be taught in more typical pedagogical settings.

This constant seeking led Redmond to places few drummers go for their education—on her travels, she began visiting ruins, shrines, and museums in the Mediterranean world. Here again she took a disadvantage—namely, the incessant touring musicians must do to earn their living, with all the empty time it entails—and turned it into an opportunity to track down materials that would later play a prominent role in her writings on frame drums.

But she was also learning from her performing experiences, and the risks she routinely took in them. “I once drummed for two days while a group of Catholic nuns meditated,” she cited as an example. She was a gifted teacher, and soon found that this kept her just as busy as concertizing. Even before she had published any of her research, people were seeking Redmond out, because they could sense she had wisdom to impart, and not just about drumming techniques. She was creating a kind of holistic musical practice, one that invited both their emotional participation and spiritual growth—whether they were already trained musicians, or newcomers.

“I discovered I had a knack for teaching other people who weren’t musicians,” she later explained. She came to realize that this required a completely different approach with unconventional priorities. With her students, she would emphasize breathing, feeling, and listening, to a degree that’s rarely practiced by music teachers. She sometimes had students walk to the rhythms they played—hardly something you would do preparing for a concert hall career. Visualization and meditation techniques also impacted her teaching.

It may seem strange, but this was almost the perfect way to teach music in an age of mind expansion and consciousness raising. But very few people were doing it. And not many outside Redmond’s immediate circle recognized what she was contributing until the publication of When the Drummers Were Women in 1997. Here she presented the accumulated learnings of her work as a researcher, performer and teacher. In my opinion, it’s one of the most significant books on music from the last thirty years.

I wish Redmond had published more—or that other scholars would do more to build on her legacy. But to her credit, she was constantly involved in educational projects, and got deeply involved in making videos and films. She was also reaching out to others in varied ways, working to build connections between different traditions and perspectives. In 2007 she moved to Brazil, where she stayed until 2009, and this gave her a whole new setting to make these linkages, and share her knowledge.

This outreach is the story of her life, and she continued it even after entering hospice in 2013. Her final message to friends is inspiring, and she concluded it with this passage from the Epitaph of Seikilos, an inspiration for one of her recordings:

As long as you live, shine, be radiant!

Let nothing grieve you beyond measure.

For your life is only too short and time will call for you.

Addendum (August 7, 2021): A few days ago, when I was writing about Layne Redmond (1952-2013), I tried to find our correspondence—but without luck. But today while unpacking, it showed up magically. These pages (with comments from Layne in blue) are from 2002. Made me miss Layne all the more.

Band in which the frame drum anchors the beat: The Chieftains.

Fascinating read Ted. Redmond's time in Brasil brought to mind a song by Gal Costa called "Bumbo Da Mangueira" in which the surdo sounds like the mother beat of the heart.